Boot camp: (In)Corporations of Fairy Tales in ABC’s Once Upon A Time

Moretti argues there is at least one “consequence of [the network model] approach: once you make a network of a play, you stop working on the play proper, and work on a model instead: you reduce the text to characters and interactions, abstract them from everything else, and this process of reduction and abstraction makes the model obviously much less than the original object” (4), leading me to wonder whether there’s value in the network model approach in folklore studies; is the network model appropriate for exploring and ideally illustrating the use of a fairy tale character despite and/or because of its specific placement in plot? What are the potential benefits of seeing folklore from a network perspective than from, say, the database of the ATU? For my boot camp, I decided to explore the potential of network diagrams with Once Upon A Time, which is of particular interest because of its constant allusions to Disney fairy tale films, and the dense network of fairy tale themes this move invokes.

In my first diagram, I attempted a simple and somewhat failed attempt to illustrate how Once Upon A Time combines two previously independent networks, or tales (fig. 1) – in this case, the previously independent tales of “Rumpelstiltskin” and “Beauty and the Beast.” However, this diagram only indicates that two tales overlap, and provides no supplementary qualifications for this relationship. After experimentation, I ended up with a Venn diagram to represent my network (fig. 2). This Venn diagram attempts, like Moretti, to “make visible specific ‘regions’ within the plot as a whole; subsystems, that share some significant property” (4). Venn diagrams comparatively evaluate data, which I use to demonstrate the “regions” of plot (that of “Rumpelstiltskin” and “Beauty and the Beast”) ABC constructs in Once Upon A Time’s narrative by sharing significant tale attributes (e.g. character associations).

Thus “Rumpelstiltskin” is also the Beast from “Beauty and the Beast.” But this narrative is further complicated with ABC’s explicit allusions to Disney’s version of Beauty, Belle, who shares the same name and attire as ABC’s live action version; “Rumpelstiltskin,” “Beauty and the Beast,” and Once Upon A Time collapse into each other under the umbrella corporation of Disney, owners of ABC since 1996. This Venn diagram ends up illustrating Disney’s corporate ownership of specific tale attributes (Belle) and ABC’s consequent (legal/legitimate) ability to manipulate Disney associations, simultaneously enacting folklore’s transformative gestures as well as corporatized indications of self-reference that actually paradoxically close off the network of folkloric associations in favour of expanding economic investment. In the densest part of the Venn diagram, we have the most convoluted manipulations of the folklore network for the consolidation of corporate ownership through cable network television.

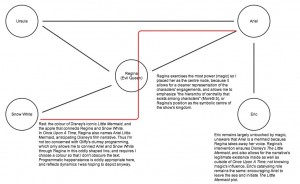

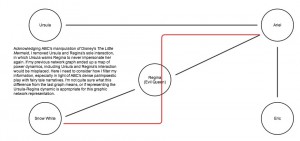

This almost hegemonic assimilation of two or more tales continues and becomes a hallmark trope of Once Upon A Time. My third through fifth diagrams examine “Ariel,” the episode dedicated to “The Little Mermaid,” which unsurprisingly emulates the Disney version by referencing Ursula (unknown to the tale-type prior to Disney), Ariel (once again, Disney specific), and clothing the titular character in the same attire Disney created over a decade ago. In fact, “Ariel” is fascinating precisely because ABC capitalizes on Disney’s copyright ownership and elaborates upon The Little Mermaid while enabling its narrative: while Prince Eric appears in the episode, his knowledge of Ariel is minimal and can actually inform the movie’s catalyzing romantic plot;

prior to Regina’s (the Evil Queen from “Snow White”) impersonation of Ursula, Ariel believes Ursula is only a myth, and thus ostensibly would not have sought the sea witch out in the film if not for the knowledge Once Upon A Time imparts upon her; Regina actually names Ariel Little Mermaid, becoming ABC’s narrative consolidation as well as corporate nod to their parent company. Thus Regina is the centre node of my network diagram, because her character not only fuels the narrative with her machinations, but visually marks the centripetal structure of the corporate networks at work.

“No interaction is crucial in itself. But taken together, they perform an essential reconnaissance function: they make sure that the nodes in this region are still communicating: because, with hundreds of characters, the disaggregation of the network is always a possibility” (Moretti 9). This is where suspicion informs my plotting of ABC and Disney networks: no interaction is crucial, but as the removal of Regina makes clear, the Evil Queen’s interactions are in fact crucial to legitimizing the combination of Snow White, the Little Mermaid, and even more tales in Once Upon A Time. The enforcement of Disney’s network through self-references legitimizes these fairy tales as Disney’s property, and “with hundreds of characters, the disaggregation of the network is always a possibility.” Thus, we have the Evil Queen, a tyrannical monarch who colonizes various tales under Disney(‘s)World, a self-enclosed narrative where transformations are only variations of their own copyrighted characters, and the transmission and transmutation of tales have shifted from the public sphere to the privatized corporate one. As much as my first diagram attempted to illustrate two previously closed-off networks opening affiliative possibilities, what my diagrams have made visibly evident is that these networks seem to have become increasingly more (in)corporated.

Works Cited

“Ariel.” Once Upon A Time. ABC. 3 Nov. 2013. Television.

Moretti, Franco. “Network Theory, Plot Analysis.” Literary Lab 2 (May 2011).