The Viewers’ Remixes & Supercuts: (Re)Ordering Content and/or Mess

Mess is inevitable: it is in our thought-process, our social interactions, our work, our mistakes and accomplishments, but most importantly it is also there in the creative process. When looking for supercuts on the internet, this website leads you to an archive of supercuts, which provides a definition for them:

Supercut: noun \ˈsü-pər-kət\ — A fast-paced montage of short video clips that obsessively isolates a single element from its source, usually a word, phrase, or cliché from film and TV. Supercut.org collects every known example of the video remix meme.

This ‘obsession’ creates a framework, a sort of viewer’s critique that highlights how this single element is repeated (and thus circulates) throughout a variety of different circumstances, events, or sources. For example, by isolating a sentence from the Wizard of Oz movie the following supercut shows how a single element can spread and circulate in a series of different contexts (networks) to ultimately become a popular culture reference:

Supercut of a Line from the Wizard of Oz

Simon Owens who writes about the impact of supercuts in the shape of nostalgia gives numbers to the general amount of editing in one single supercut, mentioning that in “2011, Baio analyzed a database of over 146 supercut videos and found that ‘the average supercut is composed of about 82 cuts, with more than 100 clips in about 25 percent of the videos’” (Owens). The extensive editorial effort provided by the creators of supercuts points to the difficulty of finding ways to order what must first appears to be a messy pile of data.

As an aspiring scholar myself, I found their creative—and yet—rigorous method intriguing enough to dig a little deeper. Could supercuts make visible the network patterns that John Law describes as running “wide and deep – that they are much more generally performed than others” (Law 385), thus illustrating how “network patterns that are widely performed are often those that can be punctualized…because they are network packages – routines – that can, if precariously, be more or less taken for granted in the process of heterogeneous engineering” (Law 385, his emphasis). Considering how supercuts create “a kind of ‘Aha!’ moment when a Hollywood cliché that you perhaps never fully internalized is laid out for you” (Owens), I would argue that they are disrupting force—perhaps even (when shared and spread) a resistance—to the sort of formulaic engineering of inserting certain overused tropes (or references) within the content of a film or series. Why would the phrase from the Wizard of Oz be used so many times? The actor-network theory might explain it in part. By alluding to the Wizard of Oz, the writers are making a reference to something that is familiar to a vast number of people, and thus this phrase becomes an actor in a grander scope of networks (viewers). This phrase has the power to connect the writers’ content to a complex spectrum of effects spreading from nostalgia to comedy.

Since supercuts isolate elements that could have been lost in a sea of content (massive amounts of unseen and/or unrelated movies and/ or television shows), could supercuts also be, in way, a punctualization? While the digitalisation of television and cinematographic content aids the phenomenon of supercuts, “these forms can be traced back to pre-digital technologies of the 1970s (in the case of Penley’s Star Trek fan videos) or the pre-YouTube and Web 2.0 participatory sharing (in the case of Cover’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer fan videos, distributed through newslists, email and private website)” (Cover). By now being able to ‘binge-watch’ a whole series (which can sometimes amount to eight or nine seasons of twenty plus episodes) due to the digitalisation of content, viewers of such content appear to have new ready tools to engage with, share, and modify massive amounts of data.

Rob Cover argues that despite this blossoming of digital methods and tools, “there has emerged a methodological gap requiring new frameworks for researching and analysing the remix text as a text, and within the context of its interactivity, intertextuality, layering and the ways in which these together reconfigure existing narratives and produce new narrative” (Cover). The way supercuts organize and order their content could be an example of how massive amounts of content could be framed in order to highlight the interactivity and intertextuality of their content.

The ‘methodological gap’ to research and analyze the remixes (and/or supercuts) that Cover points out is not unlike the one that fostered Law’s interest “in rehabilitating parts of the mess” (Law 4). Hence by trying to find frameworks in order to include (and assign meaning) viewers’ and/or fan-based’ works, we are simultaneously trying to imagine new ways to include messy bits into our methodology. The inclusion of those types of media in research is particularly relevant to Lawrence Lessig, who argues that text “is today’s Latin,” since it is “through text that we elites communicate…For the masses, however, most information is gathered through other forms of media: TV, film, music, and music video. These forms of ‘writing’ are the vernacular of today,” and ultimately adds that for “anyone who has lived in our era, a mix of images and sounds makes its point far more powerfully than any eight- hundred- word essay in the New York Times could” (Lessig 68-69). To illustrate the potential repercussions of combining arguments with media, follow through this experiment: would this clip demonstrating how a character manipulates individuals with pop culture references to create a ‘community’ reinforce Law’s argument that “our communication with one another is mediated by a network of objects – the computer, the paper, the printing press….that these various networks participate in the social. They shape it” (Law 382)?

Short Clip from Pilot Episode of the TV Show Community

Also, could this type media thus be used not only to shape our social networks and interactions, but also to “overcome your reluctance to read [Law’s] text” by reinforcing “the social relationship between author and reader” (Law 382)? Could then supercuts be considered as the product of a distant reading, and if they are, could they represent a different media (other than writing) to reveal patterns and networks between non-obvious elements? Most importantly for my case, would considering this media as a potential way to enlarge or enrich our methodology enable us to tackle down more complex and messier concepts?

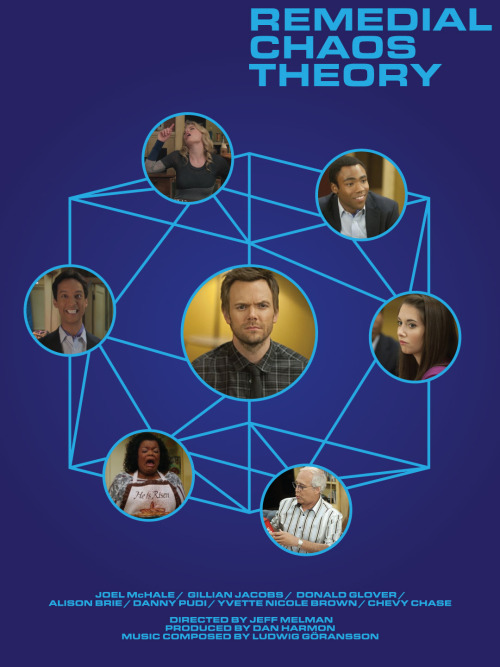

Consider the complexities that arise in an episode from the TV show Community entitled “Remedial Chaos Theory” in which the interactions between the characters diverge and/or converge when a person must leave the room to go get pizza.

They roll a die to determine who gets to leave the room, and this sequence is repeated to show each of the seven plausible (and very different) storylines contained in this episode. A supercut would make a montage of the repetitive sequences, namely the rolling of the die, and discard the variants. However, take a look at another type of fan-based/viewers clips that was created, and reminisce Law’s leading question, “‘would something less messy make a mess of describing [mess]’” (Law 4):

Juxtaposition of Content rather than a Supercut

This clip—and other similar ones–cannot be called supercuts since they did not in fact isolate repetition. They created instead a patchwork that allows the viewers to notice all the repetitions while viewing all its parallel differences. These clips could also represent the compilation of data before the massive editing (such as in supercuts or essays): before discarding the bits that do not fit to seek a pure pattern, a seemingly complete repetition. These clips are messy, noisy, heterogeneous, and relevant, “because that is the way the largest part of the world is” (Law 4). The reluctance to order something that is already complex, the surviving mess in those clips points to Law’s argument that “Clarity doesn’t help. Disciplined lack of clarity, that may be what we need” (Law 4). By not adhering to a massive edits (but instead minor ones, to juxtapose the storylines), these clips thus show a much more complex and richer patchwork of parallels, repetitions and variants.

These clips “broaden method” (Law 4), by not ‘obsessing’ with “clarity, with specificity, and with the definite” (Law 4). These clips can be used as a parallel for the moment when someone conducting research is facing a multiplicity of data converging and diverging in places, noisy and messy at times but also repetitive and similar at others. Should we then attempt to ‘Other’ “Everything that doesn’t fit the standard package of common-sense realism…Everything that is not independent, prior, definite and singular” (Law 8)? Or should we attempt to use this mess as the creators of those clips did, to better understand its source? How can we understand the complexities of mess if we can only use methods that ultimately order—and thus alter—it?

Works Cited

Lessig, Lawrence. Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. New York: Penguin, 2008. Web.

Law, John. “Notes on the Theory of the Actor Network: Ordering, Strategy and Heterogeneity.” Lancaster: The Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University, 1999. Revised 2003. http://www.comp.lancs.ac.uk/sociology/papers/Law-Notes-on-ANT.pdf

–. “Making a Mess with Method.” Lancaster: The Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University, 2003.

http://www.comp.lancs.ac.uk/sociology/papers/Law-Making-a-Mess-with-Method.pdf

Owens, Simon. “How the Supercut Changed the Shape of Nostalgia.” DailyDot. 23 August 2013. 12 September 2013.Web.

http://www.dailydot.com/entertainment/supercut-nostalgia-history-slacktory/

Cover, Rob. “Reading the Remix: Methods for Researching and Analysing the Interactive Textuality of Remix.” M/C Journal 16.4 (Aug. 2013). 12 Sepember 2013. Web.

http://journal.media-culture.org.au/index.php/mcjournal/article/view/686