Drug trafficking as a Cultural Event: Pablo Escobar and Fernando Botero

Introduction

Fernando Botero and Pablo Escobar are an example of the paradoxes of a society mired in contradictions and paradoxes, where beauty, art and culture coexist with violence, hunger and death. Both are anomalous, complex subjects. The junction between the words of Botero and the death of Pablo are examples of events and things that broke Colombian and Latin American history in two. They express a multiplicity, a discontinuity. An archaeological perspective allows us broaden the understanding of the significance of the drug trafficking concept, the ways in which some of Botero’s art work were made and a complex web of events where Colombian drug traffickers and artists are established as subjects of discourse.

Foucault showed the philosophical and historical value of research about the anomaly. He taught the importance to pay attention on the marginalized. He pointed out the analysis of madness and prisons. Also he insisted about the relevance of studying the infamous men. The French philosopher considered (1979) that to rediscover the splendor of these situations and characters or “life-poems”, as he called to infamous men, we had to submit a certain number of simple rules:

- that it should be a question of personages having really existed;

- that these existences should have been both obscure and unfortunate;

- that their story should have been told in a few pages or better in a few sentences, as briefly as possible;

- that these narratives not simply constitutes strange or pathetic anecdotes, but that in one way or another they should have really taken part in the miniscule history of these existences, of their misfortune, of their rage or of their uncertain madness;

- And that in the shock of these words and these lives should be born again for us a certain effect mixed with beauty and fright (Foucault, 1979: 78).

I have tried to follow these rules to introduce Pablo Escobar as an example of infamous man. This personage obliges us to reread the history of Latin America in general and Colombia in particular. His biography is a breaking point, anomalous event, and the confluence of a multitude of social, political and cultural factors which we do not understand yet.

The Foucault’s point of view

Foucault and his teacher Althusser criticized the traditional notion of history (1998: 281). According to Foucault there are diverse ways to write history and historian’s attention has shifted from long periods of time, “ages” or “centuries”, towards a phenomenon of rupture and discontinuity (Foucault, 1989: 47). That same notion of discontinuity has changed and is positively valued in relation to its historic function (Foucault, 1998: 299). The discontinuous is valued as a positive element that determines the object of study and validities its analysis. In order to systematically apply the concept of discontinuity we must free ourselves from notion as tradition, influence, development, evolution, spirit or age’s mentality, and other similar concepts, to focus our attention on the multiplicity of disperse events (Foucault, 1998: 302; Deleuze, 1988: 2, 13-14). Any attempt to or manner of grouping them under a general category is already an arbitrary method of documenting and making history (Foucault, 1998: 281, 300; Cfr. Deleuze, 1988: 12-13).

A way to unify, group or individualize by imposing an external or internal order are the ideas of “book” and “oeuvre”. However, once there is a detailed analysis of these alleged units, it turns out that the unity of the book is not homogeneous. The relation of a book with other books is varied and complex, it sets up a field of discourse, it is found to be interwoven in a network with other books, texts and phrases. The notion of oeuvre is less stable and hence a more problematic unit. It does not respond to that which can be represented by its proper name, the only unit that can recognize in the work of an author is a certain function of expression (Foucault, 1998: 303-305).

Moreover, there are other usual forms to organize the discourse and reduce its discontinuous character. One is to refer it to a secret and unrecoverable origin. This view requires a search for a supposed origin or a principle that escapes us. Another form is to assume that all discourse is based on something already said, but not in the sense of that which has been pronounced or written, but in the sense of something unsaid, in an underground sense, which must be interpreted. Consequently, the new way of making history leads us to investigate the discontinuity of events in a discursive space that is articulated just as it is stated. The question that guides us is what is this irregular form of existence that comes to the light from what is said but not in any other place? (Foucault, 1998: 305-306).

The discourse analysis that Foucault proposes does not only points towards the declarative event, considered independently, but tries to understand how these statements, in their specificity and discontinuous character, are articulated with other events that are not of a discursive nature but that are of an order economic, social, political, artistic, etc. completely different. According to Foucault, archive work should lead us to the analysis of what he calls “monuments”, the symbols through which we conserve events and things, with the intention of understanding the language game that determines in a given culture or society the appearance and disappearance of statements, its persistence and its disappearance. The archaeological analysis is then centered in how objects are constituted, subjects positioned and concepts formed (Foucault, 1998: 303-305; 324-325).

Along these lines I would like to shift our attention to a series of specific statements, made by a concrete individual within the framework of a complex network of disperse historical, social and political events, whose appearance is connected to singular artistic objects, by means of which discursive subjects worthy of mention and recognition are positioned.

The Encounter between Fernando Botero and the drug trafficker Pablo Escobar

In the context of the war between drug trafficking Cartels, the Cali Cartel planted a bomb in Pablo Escobar’s house, he was perhaps the most famous Latin American drug trafficker. During an interview the Colombian artist Fernando Botero recalled this event, which occurred in 1993, and said the following: “When they put a bomb in Pablo Escobar house, they emphasized the fact that he had a Botero in his house and this resonated widely with the Colombian press. So, I asked the director of the newspaper El Tiempo to write an editorial and inform the public that I felt repugnance due to the fact that Escobar had one of my works. My journalist friend suggest me to leave the country for my safety after writing the editorial, and so I did, I packed and went to Europe”

However, the “paisa artist” not only said the previous statement but also painted several pictures of Pablo Escobar’s death. These paintings have generated controversy. Fernando Botero is a Colombian painter (born in Antioquia just like Pablo Escobar) who has been recognized internationally for his artwork in a very particular style. Botero is considered to be the most valued living Latin American visual artists in the world. This Colombian artist has shaped Latin America from different angles such as religion, the family, the street, bullfighting, the circus and the violence. His classic fat figures make him unmistakable, although he denied that his work is “images of fat people”, but that, according to him, the volume is the most important element as “in the works of Van Gogh, for example, it was the color”, and in a press conference he emphasized that “the volume is applied to everything, I apply the roundness to everything. My works are sensual because of this”.

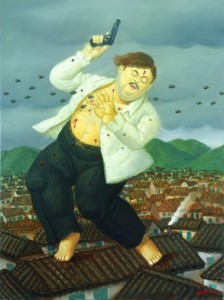

“Pablo Escobar Muerto” (1999), is an example of how Botero can express an historical event through his works of art. There Botero expresses his version of the drug trafficking Lord fleeing across the roofs of Medellín, just before being taken down by the police on December 2nd, 1993. The painter represented Escobar as a giant on the roofs of several houses with “bullets raining down” and in the background a landscape out of a typical “small town” of Antioquia, although not necessarily the city of Medellín. ”Fernando Botero recently affirmed that the idea is that in the future people will remember the tragic moment endured by the country, so as to not repeat it ”, and added ” I love my country. The proof is in the three thousand paintings that I have painted inspired by its reality ”.

The artist does not try to glorify the person or the scene, but instead represent in his paintings events related to Colombia’s violence and the drama of drug trafficking. This work is connected to another painting made public by Botero in 2006, a painting titled “La muerte de Pablo Escobar”. This painting shows three characters: a police officer, a women and Pablo Escobar, with the traditional robust silhouette that characterizes Botero’s style. The size of each character indicates a hierarchy: Pablo is a giant that preferred his tomb in his country full of mountains and traditional small towns than a jail in a modern city in the United States. The police officer is next in importance, timidly showing with his finger and face full of disbelief that Escobar has passed away with a pistol in his hand, and, finally, the woman has her hands placed as if praying and her face as if he were before a martyr or saint. The painting clearly shows the drug lords place within the social conception, for some he was a villain, but for others he was a hero or martyr: “He helped the poor and died fighting”.

In “Pablo Escobar muerto” the discontinuous becomes present, the singular and unique event, in this work we see the gangster boss lying on the roof of a house after he was riddled with bullets, but in a position as if he were sleeping, as if he had not died. From below, in the street, at a distance, a police officer points as if showing the woman next to him that from the moment of Escobar’s death the history of drug trafficking will no longer be the same. Pablo turns into a model to be imitated that is revived in each new drug trafficker that follows his footsteps through this “valley of tears”.

These Botero paintings show the tragedy of a complex society molded by catholicism and Capitalism, divided between rich and poor and between those who love Pablo and those who hate him, between those that reject drug trafficking and those that accept and coexist with it. Botero and Escobar are an example of the paradoxes of a society mired in contradictions and paradoxes, where beauty, art and culture coexist with violence, hunger and death. The junction between the words of Botero and the death of Pablo are examples of events and things that broke Colombian and Latin American history in two. They express a multiplicity, a discontinuity. An archaeological perspective allows us broaden the understanding of the significance of the drug trafficking concept, the ways in which some of Botero’s art work were made and a complex web of events where Colombian drug traffickers and artists are established as subjects of discourse.

Bibliography

Deleuze, G. (1988). Foucault. University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis, London.

Foucault, M. (1979). Michel Foucault: Power, Truth, Strategy (Vol. 2). Feral Publications. University of Sidney, Australia.

Foucault, M. (1998). Aesthetics, method, and epistemology (Vol. 1). The New Press. New York.

Foucault, M. (1989). Foucault live: (Interviews, 1966–84)(S. Lotringer, Ed., J. Johnston, Trans.). New York: Semiotext (e).

To inquire about Pablo Escobar:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sp4KkJ12aPQ

Pablo Escobar – King of Coke – 2007 • Full Movie

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qwuud6vwkhw

Hunting Pablo Escobar HD Documentary National Geographic

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GEQW2QkPSmo

Pablo Escobar – King of Cocaine

To inquire about Pablo Escobar’s death:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jxj1JbWQe8g

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9IkQVBhKivs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GvsbvbR4AZQ

Pablo Escobar’s Death

To inquire about Fernando Botero’s paintings:

https://www.museodeantioquia.co/exposicion/salas-fernando-botero/