Probe: Out on a Limb with Branching Narratives

Where are the procedural boundaries of an infinite story?

How does the invisible render the visible meaningful?

Is the true tree-narrative actually the structure of a network?

Branching narratives are less objects than they are procedural systems. Usually when we talk about nonlinear, branching storylines, we think of either the popular Bantam line of Choose-Your-Own-Adventure (CYOA) gamebooks or video games with multiple endings based on the ethical decisions characters have made throughout the game’s story. But in truth the tradition goes further back than this, all the way back to the Dada movement. It was in the 1920s that Dadaist Tristan Tzara first suggested creating a poem by cutting up words from the newspaper and mixing them together before drawing them from a bag one by one to create a new piece of verse. (Tzara VIII) Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs would later adapt this practice into what they called the “cut-up method”; and while it may sound like poetry created through a system of randomness removes all choice from the hands of the participating user (rather than ‘readers’ or ‘writers’), what’s important here is the existence of multiple possibilities at every moment. Just like a choose-your-own-adventure story, the user doesn’t necessarily know what’s next, what effect her next decision will really have. The central difference between cut-up poetry and CYOA books is that in the latter the user believes she has a slightly better idea of outcome. This is because at every fork in the CYOA narrative, she’s given one of several options, whether to reason with an attacker, turn tail and run, or maybe fight back. But this autonomy extends only over a given character’s decisions (usually the protagonist’s), not how the reality of the narrative will treat these decisions (it could be doing something relatively safe like picking up a phone turns out to spell doom for the story’s hero, quite incomprehensibly). In the cut-up, the user has no idea what will come up next, but with a good enough memory, every new branch on the tree will come up as familiar, because it’s the user who cut up all the words in the first place. Furthermore, the procedural nature of both the cut-up and the CYOA story both allow for replay to increase the chances of cognitive profit. The user is scripted by the environment of the rules as well as able to act upon it; at every wrong turn, she’s reminded of the multiple possibilities of the moment, “in which all the quantum possibilities of the world are present.” (Murray 7) The user can experience all these possibilities if she chooses to, without necessarily privileging any given one as the single choice.

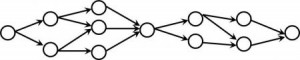

A CYOA diagram of Journey Under the Sea by Michael Niggel. For a blow up click here: CYOA-Michael-Niggel.

Another strain of thinking might treat methodological examples like these as what’s commonly known as interactive fiction (or IF), a term most often applied in thinking about games. From text experiences like Adventure to role playing games like Dungeons and Dragons to AAA studio releases like Deus Ex or Fable, in most interactive fictional experiences, just like in most CYOAs or cut-ups, it’s the author/programmer who lays out all the possible passageways, constructs the architecture of the experience, but it’s always supposed to be the user who does the navigating. The following of the twisting path controls the revelation of the narrative, consequently proposing the argument that the narrative is actually generated by the interactive process (Montfort 3). But does this make for a true branching narrative? The real tree structure may have no ending, and a game can only contain so much code, a book can only contain so many pages, and a bag can only contain so many cut out words. Because of the limits of programming, most branching narratives (both digital and analog) tend to resolve the issue of infinity with convergence, the same type that Moretti talks about with Kroeber’s Tree of Human Culture (Moretti 54). A lot of the time in branching narratives, different choices made at different points will lead to the same conclusion. This means in the CYOA book the pure tree structure of the story is a bluff: the user can’t have two choices on page a that both take her to page c, but she can have one that takes her there from page a and one that takes her there from page d. In games it’s even harder, mostly because to build a game is so very difficult and time-consuming. The popular open-world Fable franchise, for example, in part built its original reputation on the promise of user ethics affecting game-character and narrative—in a given situation the player could choose to do the ‘good’ thing or the ‘evil’ thing. However, more often than not both choices yielded the same or extremely similar results for the player’s advancement in the game and the overall story; the real differences were in the game hero’s appearance, the shabbiness of the environment, and the player’s emotional experience (and even this is a subjective claim). However free Fable may claim to be (“the options are obvious – the decisions are up to you,” claims Fable III’s slipcase jacket), the game actually only offers a very narrow range of pathways.

While your ethical choices control the look of Fable‘s protagonist, the narrative outcomes are largely the same. Image from Fable Wiki.

Space restraints keep me from going into more elegant examples of IF (any one of which would take me a long time to unpack, and Nick Montfort’s already done it better than me anyway). Suffice it to say that the real branching storyline is one written entirely by the user, and so far, the few examples that exist are arguable at best. Certainly truly nonlinear rarely even have stories articulated further than ‘goals’. (Sorens 4)

In any full branching narrative, the options have to be connected together so that the user ends up caught in a maze rather than making her way through the splitting veins of a boundless organism. Even Borges’ Garden of Forking Paths is just that: a garden where every point leads to every other. It’s a hedge maze—huge, but hardly infinite.

In a branching narrative, most continuity problems are solved by occasionally routing multiple decisions to the same point for the sake of finitude.

So the truth about the tree is that it’s not a tree. It’s a network, with not a trunk but rather occasional central points where things gather up or channel together. The tree is the chronology of your own starting mark, that point of entry from which you began the exploration. Even Moretti alludes to this no later than his introductory paragraph:

Theories of form are usually blind to history, and historical work blind to form; but in evolution, morphology and history are really the two sides of the same coin. Or perhaps, one should say, they are the two dimensions of the same tree. (43)

Without time and your participation, a tree can’t look like a tree. It’s the same in data analysis as it is in evolution. So history is the crux of the tree’s usefulness as a methodological tool. However, Moretti also ties the passage of time necessarily to evolution; he doesn’t take into account the possibility of wasting time. These are the notions I found myself starting to suspect: First, the inferred proposal that trees can be useful without time (I believed that the flattening of the temporal dimension in a tree would render it instead a network and reveal all the ‘branch’ lines that a history-centric view had rendered invisible), and once that was resolved, the idea that the passage of time always subtends evolution. It’s a concept problematised by the existence of convergence, and if you think in terms of networks, then potentially everything is a result of convergence before anything has a chance to diverge. Conversely, Moretti tells us that convergence only arises on the basis of previous divergence, so it seems that it’s a chicken-and-egg argument: all things are products of other things coming together, but those things had to come from somewhere too, and any genealogist will tell us we can only trace the lineage so far back.

Jason Shiga‘s April Fooled.

But on to our final branching narrative (and simultaneously back to wasting time—convergence at play). It seems to me that the best way to illustrate the tree’s network nature, much more akin to Kroeber’s tree of culture than even Moretti’s diagram shows, is to look at a tree within a network of convergences—a social network. What narrative forks and branching more than the personal one you access every time you explore your Facebook feed and meander your way through the never-ending stream of posts? None of it follows from any logic but your choice—it’s the story of how you spend your day peppered with the occasional contribution (or recapitulation of someone else’s contribution). Like every other branching narrative, what’s made present can only be constituted by what’s rendered absent, invisible. You can’t follow every pathway and click on every link; I once tried to just expand five years of posts on my wall (without even following any of the links), and it took me nine hours. (Sinervo 2) We finally have the potentially limitless story, even if it is a story as disorganized as the Internet, but we’re bounded by our own abilities as readers. More importantly, just like all the other branching narratives, this one is a network, and one where our most consistent decision is to double back on the branch we’re hanging from – after all, the back button always need to be clickable before the forward one.

WORKS CITED

Borges, Jorge Luis. “The Garden of Forking Paths.” Labyrinths. Trans. Donald A. Yates, James E. Irby. New York: New Directions, 1962.

Burroughs, William S. and Gysin, Brion. The Third Mind. New York: Seaver Books, 1978.

Crowther, Will, and Don Woods. Adventure. PDP-1/FORTRAN. Numerous publishers, 1975-1976.

Eidos Montreal. Deus Ex: Human Revolution. Square Enix, 2011. Xbox 360.

Lionhead Studios. Fable III. Microsoft Game Studies, 2010. Xbox 360.

Montfort, Nick. Twisty Little Passages: an Approach to Interactive Fiction. London: The MIT Press, 2005.

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History – 3.” New Left Review 28 (Jul-Aug 2004): 43-63.

Murray, Janet. “From Game-Story to Cyberdrama.” First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game. Ed. Noah Wadrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan. London: The MIT Press, 2004.

Sinervo, Kalervo A. “A Never-Ending Exercise: Facebook as an Apparatus of the Incomplete Self.” Unpublished article. Montreal, 2010.

Sorens, Neil. “Stories from the Sandbox.” Gamasutra. 14 February 2008. Web. 31 October 2013.

Tzara, Tristan. “Dada Manifesto on Feeble Love and Bitter Love.” 391. 12 December 1920. Web. 1 November 2013.

http://www.ted.com/talks/barry_schwartz_on_the_paradox_of_choice.html