probe–one flat thing

What would embody ‘counterpoint’… It is kinds of alignment in time. Ways to establish identity. It could be spatial, linear, the form of something… It could be the rate of appearance [of new alignments]. In any categorical level of description there can arise ‘identity’ and you just have to bring that forward and say to the public, now you are going to look at the way things [emerge]… not the things themselves but the distribution of their timings… things that are similar enough to awaken the recognition of identity… so for me this ability to recognize identities is the emergence of pattern… Once the brain has got it… it looks for the next pattern… brains are naturally curious. What is the brain’s sense of interest? What is the brains timing of interest? (William Forsythe, choreographer)

Last week Siegert prompted a question about Hylomorphism describing a question of the relationship of form to matter in which relationship he states, “matter does not matter in terms of what is essentially needed in order for the being to be.” (Siegert, 16) This he relates to Deleuze and Guatari’s smooth and striated space, as an antidote to hylomorphism, where material or matter, before becoming form, belongs to smooth space and the world of disciplined and ordered things (of form) belongs to striated space. That is, the matter does matter but the question is how to see it’s pattern, its weave. Here he takes the map of Vermeer and Visscher, or rather the weave of fabric upon which the representation of the map is painted, and upon which in turn are painted waves and tiny ships sailing, and through which in turn we see a seventeenth century scientific world view, as a place to begin. As with Lewis Carroll’s maps, the ocean becomes a metaphor (?) for smooth space, a space prior to meaning. He proposes a different “metaphysics of space” more related to textile with its “folds bends and bubbles” as different from that of geometric space to be included in the “materiality of the map interfering with its contents, as the medium of representation interferes with the representation of the territory…” (16)

Graphs, maps, and trees seem, in Moretti’s terms, to be processes or gambits for stepping aside from representation and meaning conventionally (hermeneutically) viewed. A gambit is a temporary strategy at the beginning of a chess game, a provisional syntax designed to open up the territory. We have moved from the diachronic (graphs), to the spatial (maps) and now on to ‘form’ changing over time with trees. For Morretti: “After the diachronic diagrams of the first article, and the spatial ones of the second, trees are a way of constructing morphological diagrams, with form and history as the two variables of the analysis… charting the regular passage of time… and the formal diversification.” (Moretti 45) If we chart, or graph or ‘tree’ these variables, this distance viewing gambit should allow us to see patterns beneath what we see as ‘form’ and what we see as time seen as the history of a form (‘see’ is important here, since we are relying on our processing the visual in this gambit). My question for this probe is two-fold: 1) Is what we see as a pattern something from out there in the ‘material’ of matter or is it a product of our own very fascinating perceptual patterning of all sense information and 2) What are those lines and forkings (the actual black things on the paper) in Darwin’s drawing or in any tree; what do we ‘mean’ by them? Does the line mean a degree of similarity, leading to change? Does the branch mean an interpretation of a rate of change that signals a ‘difference’? What’s the difference? How have we decided?

Trees are maps of perceived morphological change over time. If we back the time scale out far enough and define what is ‘change’ carefully enough a pattern will emerge. As Shalizi points out a randomly generated set of literary ‘genres’ over a similar period seems to produce a similar pattern of clusters to Moretti’s plot of the real material. (Shalizi 116) The eye sees faces in the clouds. (116) This materialist critique seems to be only a tiny bit of the story (at least in the terms of my two questions, above).

William Forsythe: One Flat Thing, Reproduced (2000) link to video

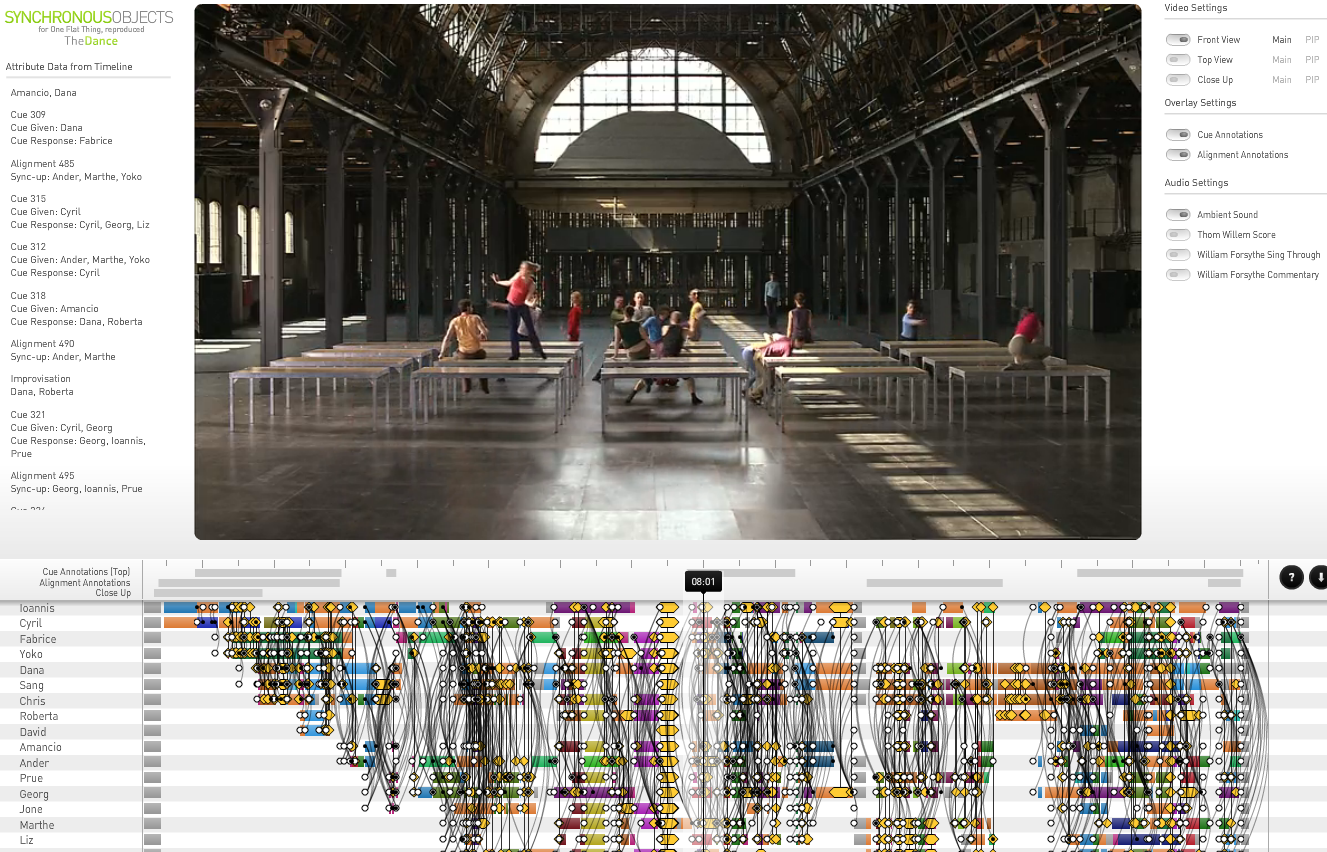

In this probe I will introduce a choreography (a dance performance) whose generative impulse seems to have been our own pre-conscious curiosity for pattern (in this case as a specific kind of pattern, counterpoint) and how that live performance, recorded in various ways, was put into the hands of specialists in data visualization in order to analyze, record or archive it in a manner that is explicitly different from what a conventional film or video document might do.

In 2000 William Forsythe devises the (approx. 20min) dance performance One Flat Thing, Reproduced in which fourteen performers interact with twenty tables in an evolving “cloud of alignments” (Forsythe, np). Forsythe describes the piece in terms of the complexity of movement, cues, gestures and repetitions with which the viewer is confronted. Working from a beginning point of early modern ballet (Balanchine) where a fugue-like structure of gesture and counter-gesture (counterpoint) is presented in a formally structured and focused way, making it possible to ‘read’ the dance much like a piece of music. One Flat Thing disperses and complexifies the counterpoint such that it is impossible for a viewer to keep up. Rather than a theatrical or cinematic focus of alignment we have a “cloud of alignments’. To viewers who ask where to look in the dance, Forsythe suggests, look everywhere (Forsythe, np). Forsythe’s intention is that we are not looking for content or expression, and the piece is not entirely composed for us. We are as viewers focused on the very threshold of our own ability to parse the cues and repetitions, to assemble the shapes that move through the piece on many levels, generating the emergence of pattern at the threshold of our brain’s ability (and curiosity). In some sense the piece proposes that the patterns are generated or projected in the intention of the viewer, that the richness of the performance has nothing to do with conventional ‘content’ but rather to the interplay of the pattern-making viewer with the pattern-cuing performance. (Intention here could be understood in relation to Husserl’s phenomenology, an attempt to understand perception at its most primal moment).

http://synchronousobjects.osu.edu/content.html#/TheDance

So if this work is about the emergence of pattern in the eye and brain’s interaction with the world what happens when Forsythe presents this work to mappers and graphers of data in a subsequent project, Synchronous Objects, and challenges them to parse the dance in different ways. Unlike music which has a conventional system of notation, dance seems to exceed the limits of any notations system (for example Laban Notation). Consequently Forsythe has been interested in this challenge of ‘translation’ over the years. Synchronous Objects was a well-funded attempt to see what experts in the field of mapping and visualizing data could come up with. Clearly what is going to disappear first is the very perceptual threshold the dance is constructed around. The search for pattern will take place in the translation of the data into other kinds of visual and informational flow. Certainly prejudices will arise that did not exist in the original, a stabilizing of the flow of time, for example (though the cue-score keeps the timing set by the dancers). In all cases the graphing, mapping or treeing of One Flat Thing is a simplification of the event onto one or another layer. Cumulatively, these representations tell us much about the dance. They also tell us much about the aesthetic preoccupations of the people making the visualizations. There are a few which fall totally into the trap of representing their own representational system or technology.

The ‘Cue Score’ and ‘Cue Visualization Tool’ seem to have the most relation to the subject of this probe: trees. Viewing these tools increases one’s ability to understand the complex cue process which the piece uses, letting us know that there is an organization here that we were unaware of, or unable to fully comprehend is our strivings to keep up with the ever-emerging patterns in the live or filmed performance.

Returning to the first question, are they patterns we see in the materiality of matter or that we build in our intention? In this work of art the answer is possibly, ‘both’, since the work desires to play with our tendency to pattern-build from the outset. Do these visualizations tell us anything about our relationship to graphs, maps and trees, as perhaps just a little too convincing in their appeal to our need to perceive pattern and to organize? Ultimately, like Carroll’s map of Germany (which exists only in its own explanation, and in Germany) the dance itself is the most effective representation of its own play, because we are playing with it (it is happening between us), not on the level of representation or analysis. As a whole, though, the maps and trees, as a gambit, help us understand this materiality of perception. Returning to the second question of the lines and forks (in the Darwin or linguistic tree); they do seem to represent out intentions, our presupposition about what constitutes difference and continuity. What is different enough to warrant a fork in a line? Red fur versus white fur? The ability to interbreed? Where the patterns, at a distance, assist in naming and organizing the world (by pretending the patterns belong to it, not us?) the lines themselves represent both our conjectures and our prejudices.

Links

Forsythe interview: http://vimeo.com/36635217

Synchronous Objects: http://synchronousobjects.osu.edu

One Flat Thing, Reproduced (dance): http://vimeo.com/36687068

Works Cited

Forsythe, William. Interviewed by Thierry de Mey (2006) (web)

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History – 3.” New Left Review 28 (Jul-Aug 2004): 43-63. (print)

Shalizi, Cosma. “Graphs, Trees, Materialism, Fishing.” Reading Graphs, Maps, Trees: Responses to Franco Moretti. Ed. Jonathan Goodwin & John Holbo. Anderson: Parlor Press, 2011. 115-39. (print)

Siegert, Bernhard. “The Map Is The Territory.” Radical Philosophy 169 (September/October 2011): 13 – 16. (print)