Probe: Instituting Errors: Glitch Imagery in Communications Networks

Gliché is a free iPhone app that promises to “distort your photos into works of digital art.”1 As characterized in a recent network-based arts biennial that featured the piece of software, it is “a free photo app to generate wrong.”2 The app adopts the aesthetics of glitches—those unanticipated and unintended technological errors—in the service of controlled, deliberate image-production.

Such glitched imagery represents an aesthetic (and set of computational processes) that has lent to sensibilities of a diverse range of cultural producers that includes artists, designers, hackers and software developers. This probe asks how glitch imagery has been used in both artistic and commercial capacities, and what to do with claims of the glitch’s radical nature.

“The break of a flow within technology (the noise artifact) generates a void which is not only a lack of meaning. It also forces the audience to move away from the traditional discourse around a particular technology and to ask questions about its meaning. Through this void, artists can critique digital media and spectators can be forced to recognize the inherent politics behind the codes of digital media”

(Rosa Menkman 340).

In visualizing technological failures, glitches (and similar ‘faults’ within digital systems—i.e. bugs, jams, noise…) compel a view past the controlled surface of the digital. Critical glitches may offer counterpoints to technological systems that rely on efficiency, accuracy and predictability. To standards of streamlined, regimented digital aesthetics, they may represent a more human-scaled information presence; to the problem of plenitude, they may enact a slowing-down or freezing of the cyberflow; to the tyranny of digital logic, they may offer absurdities outside its narrow peripheries. In their most radical instances, glitches may present transgressive modes of cultural and political engagement.

In distinction from more expressly activist strategies (seen in hacking and cracking, culture-jamming, tactical media and cyberfeminist practices) the critical glitch enacts a process of defamiliarization that thrusts “information without a purpose” onto the clean surface of the digital image (Nunes 13). It engenders a heritage of hacking that turns around the tools of a technological system to rupture itself. Here—in the digital realm—a communications system built for the transfer of clear signals is stymied by objects that are corrupted, scattered and mutated. Like Lisa Samuels and Jerry McGann propose of the deformative, deliberate misreading of literature, glitches “short circuit” conventional protocols of reading (30). These are media objects squarelyat odds with those supported by mainstream channels ofdigital circulation, and they warrant a challenge to dominant interpretive frameworks.

Within the history of communications technology, noise represents a deficit in efficient transmission. Forefathers of information theory (and harbingers of contemporary communications networks) Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver sought in the mid-20th-century to diminish noise—to send signals with “zero probability of error” (Shannon 8). This cybernetic ambition was concerned with exacting total programmatic control of information through the eradication of errors. In optimized cybernetic systems, glitches are permitted only insofar as they provide feedback for how best to sidestep them. Thus have contemporary digital communication networks maintained a glitch-free ethos that media theorist Mark Nunes describes as stemming from “a cybernetic ideology driven by dreams of an error-free world of 100 percent efficiency, accuracy, and predictability” (3).

Glitches carry excess meaning onto the digital image’s clean, superficial surface, and thrust into visibility information that is not clear, predictable, or controllable. This noise denotes a communicative malfunction: a disconnect between sender and receiver. Representing a break within its flow of information, glitches may thus offer a critical counterpoint to technologies that rely on efficiency, accuracy and predictability. Where digital technologies necessitate particular protocols of codified interaction, the critical glitch represents an unwillingness to nourish a control system in which legible feedback is crucial. They work against the predictable grain of the digital to offer up “unintended trajectories” (Nunes 8). This unexpected behaviour is the ontology of the glitch: as Cinema scholar Hugh Manon and artist Daniel Temkin describe “one triggers a glitch; one does not create a glitch.”

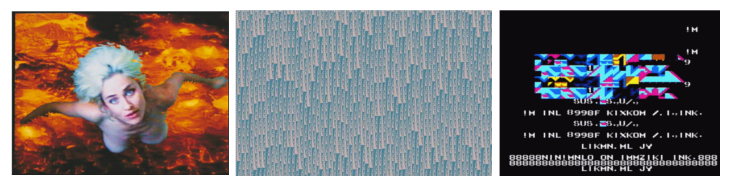

Rob Sheridan. The Social Network Soundtrack by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, 2010

Kunihiko Morinaga’s 2011-12 A/W collection for fashion house Anrealage

Still from Nabil Elderkin’s music video for “Welcome to Heartbreak” by Kanye West

“Errors come in many kinds, but increasingly, our errors arrive prepackaged” (Mark Nunes 13).

“When the glitch becomes domesticated, controlled by a tool, or technology (a human craft), it has lost its enchantment and has become predictable. It is no longer a break from a flow within a technology, or a method to open up the political discourse, but instead a form of cultivation” (Menkman 342).

Given the unpredictable nature of the critical glitch, what are we to do with the predictable, manageable glitch imagery offered by mainstream practices and services like Gliché? Such stylized, superficial glitches seem to fit squarely within the same economic logic of commerce culture media-forms, and of the pixel-perfect, efficient-signal logic of cybernetics. Artist Rosa Menkman warns of a state of “conservative glitch art,” that, as with now-institutionalized Avant-garde art and punk music, capitalizes and neutralizes the glitch (342). As electronic musician Kim Cascone has recognized, we are entrenched in a “famous for fifteen megabytes culture” in which the glitch “is a tactic of subversion that has become a fashion statement” (qtd. in Moradi 19). This prevalence of glitch-like formal design—from high-fashion to popular music production—can be shown to recuperate and defang the critical glitch, mirroring a force that, as Peter Bürger famously wrote of art institutions, “neutralizes the political content of the individual work” (Bürger 90). Here, glitches may be merely cultivated fuck-ups—happy-accidents bred for commercial results. “There is no question,” Manon and Temkin assert, “that the glitch aesthetic [has] been co-opted by mainstream media.”

Indeed, commercial markets have supported a taste for what Italian media theorist Vito Campanelli calls “disturbed aesthetic experiences” (154). Here, “flaws” of digital media are written into commercial objects, taking advantage of the fact that noise, interference, pixilation, etc. have “become part of everyday aesthetic experiences” (ibid.). Hence, synthetic or staged glitches have found their way into popular cinema (from Hollywood to Dogme 95), and into professionally-made ‘amateur’ porn. These objects, Campanelli argues, “attempt to take possession of the truth of the flaw,” benefiting from an aesthetic of imperfection that appears more ‘authentic’ within a context of over-produced, polished media (164). This phenomenon, he suggests, has arisen “in concert with generalized distrust of the cold perfection of the cultural industry as whole.” (Campanelli 166).

This taste for low-fi, crude imagery (and its processes of improvisation, low-skill manipulation, and technical transparency) has further been bred into more vernacular visual sensibilities of the digital age. As internet theorist Geert Lovink has written, “The cinéma-vérité generation’s wish for the camera as ‘stilo‘ has come true: the billions are scratching away with abandon” (11). From digital image filters that increase film-grain and nostalgia (Instagram, etc.), to videos released by hacker group Anonymous, errors in digital media are being extensively exploited by amateur image-makers. These perfected, controlled glitches (or glitch-like) images may thwart the radical potential aspired to by Menkman and her fellow glitch artists.

Do deliberate glitch-making endeavours like Gliché fulfil a kind of conservative, cybernetic imperative—recuperating errors into a mainstream logic of control and predictability? Here, error is parsed as not a way-out, but (as a corrective feedback) a means to underscore the dominancy of the system from which the error arises. Indeed, such deviations could allow for the perfecting of a system’s order and logic. As Nunes relates, “Error, as captured, predictable deviation serves order through feedback and systematic control” (12).

Conceivably, such discrepancy between ‘pure’ and ‘staged’ glitches may be a trivial argument to begin with. Though a glitched file is emphatically deranged, no irrevocable damage is committed in this apparent iconoclasm. As Manon and Temkin argue, “for all the destructiveness in glitch art, it is actually simulated dirt, simulated breakage, simulated risk.” With a low-stake capacity to ‘undo,’ glitch-making at any level does not, as Virilio speaks of uprisings, “penetrate the machine, explode it from the inside, dismantle the system to appropriate it” (74, mentioned by Manon and Tempkin).

Pipilotti Rist, Still from Selbstlos im Lavabad, 1994. Video installation.

Tony (Ant) Scott, GLITCH #12 – IT’S ALWAYS SCHOOL HOLIDAYS ABOVE THE CLOUDS. 2003. Digital image.

Max Capacity, Section Z Glitch, 2010. Still from hacked NES game.

Rather than dismantling technological systems, glitches—as visual, communicative objects—partake in an unbalancing of representational systems in the digital age. At their most radical, they do not demolish the communications networks from which they are born, but engage those networks to perform what Rita Raley calls a “micropolitics of disruption” (1). Thus has the glitch been employed by artists to figuratively rip apart, say, conventions for representing the (female) body (Pipliotti Rist), to render broken the personal computer (Ant Scott), and to restructure protocols for participating with digital systems (Max Capacity), while leaving actual bodies and machines intact.

Such critical, artistic uses of the glitch ask us to attend to our relationship with technology, but no less do the surfaces of some controlled, designed glitches compel a renewed view of technology. These images too may harbour the useless, textural noise at odds with digital logic’s penchant for efficiency and predictability. In their “failure to communicate,” as Nunes conveys, both staged and critical glitches signal “a path of escape from the predictable confines of informatic control: an opening, a virtuality, a poiesis” (3).

Works Cited:

Bürger, Peter (1974). Theorie der Avantgarde. Suhrkamp Verlag. English translation (University of Minnesota Press) 1984.

Campanelli, Vito. Web Aesthetics: How Digital Media Affect Culture and Society. Rotterdam: NAi, 2010.

Lovink, Geert, and Rachel Somers Miles, eds. Video Vortex Reader II: Moving Images Beyond YouTube. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011.

Manon, Hugh S., and Daniel Temkin. “Notes on Glitch.” World Picture 06 (Winter 2011). Web. 15 Jan. 2012. <http://www.worldpicturejournal.com/WP_6/Manon.html>.

Menkman, Rosa. “Glitch Studies Manifesto.” Video Vortex Reader II: Moving Images Beyond YouTube. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011. 336-47

Moradi, Iman. Glitch: Designing Imperfection. New York: Mark Batty, 2009.

Nunes, Mark. Error: Glitch, Noise, and Jam in New Media Cultures. New York: Continuum, 2011.

Raley, Rita. Tactical Media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2009.

Samuels, Lisa, and Jerome McGann. “Deformance and Interpretation.” New Literary History 30.1 (1999): 25–56.

Shannon, Claude. “The Zero Error Capacity of a Noisy Channel.” Institute of Radio Engineers, Transactions on Information Theory IT-2 (September 1956).

Virilio, Paul. The Accident of Art. Semiotext(e): New York, 2005

1 Writes its designer: “Glitché is a free iPhone application to distort your photos into works of digital art using several effects based on computer errors and bugs such as glitch, slitscan, datamosh and many other” <http://cargocollective.com/shreyder/Glitche-2013>.

http://glitche.com/. App designed by Vladimir Shreyder and developed by Boris Golonev and Ivan Shornikov.

Automated glitch-art generators aren’t particularly new, with forerunners like Data Glitch 2, a commercial plug-in for mainstream motion-graphics software, freeware glitch image maker Monglot, and online, real-time generators such as the canvas-API Glitchy3bitDither, animated .gif glitcher YouGlitch, javascript Glitch Images and Imageglitcher, and the iPhone app Satromizer. Gliché has received much critical attention, as indicated in the app’s Facebook photo-stream.