Probe: Gaming and Glitching

CHEATER CHEATER PUMPKIN EATER

The practice of cheating, or deceiving for gain, is witnessed throughout history from ancient warfare, i.e. the Trojan horse, to modern day practices such as tax evasion. Cheating disrupts normative social order; it disobeys the rules of a system and makes visible what was unseen before. It simultaneously functions outside and inside an assemblage, similar to the way in which Rosa Menkman describes digital noise and computers. “The computer is a closed assemblage based on a genealogy of conventions, while at the same time the computer is actually a machine that can be bent or used in many different ways” (Menkman 340).

Cheating utilizes and is utilized by many video game companies and players for a variety of purposes depending on the type of cheating employed; some cheats are initiated by game programmers and others by glitches in the game or console. Glitches inherently are not expected or strategic, but if signified the value attributed inscribes the glitch with stability and authority as seen in glitch art, which has now become a contemporary mode of expression regularized in the art world (Menkman 341). Cheating also becomes a formal mode after initial induction and thus is now anticipated by video game companies and the players, illustrated by the plethora of cheat books and websites. In “Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames” Mia Consalvo uses models of cheating to uncover connections between commercial influence and subcultures of the gaming world. Further, Consalvo states that cheating is developed by the paratextual, which is constituted by the peripheral industries such as gaming magazine articles on cheats and the companies that produce mod chips (Intro § 5 ¶ 5). Do glitches and cheating re-textualize a game? How can the change in rules or statements alter the relations in the game’s network? Is cheating/glitching ultimately a deformance and what does it illuminate about video game scholarship?

GLITCHES: GAINING AND GOING AGAINST THE RULES

The Diablo franchise, produced by Blizzard Entertainment, relies on a role playing format that engages directly with the user and can also be played online with other participants through the battle.net server. However, the user is not given total control as there are set tasks and realms in which the user must remain. “The paradoxical aim of good game design is to strike a balance between the protection of play through regulation and game design on one hand (play as rule bound) and the protection of play as free, unfettered, and improvisational activity on the other hand” (Krapp 80). By setting rules and constraints Blizzard confers its authority, but the games Diablo and Diablo II are over a decade old and thus many cheats and glitches have been disseminated on Internet forums and cheat books that are arguably the paratext. Small glitches, as illustrated in this YouTube video allow the user to follow a set of steps that result in a gain; the user repeats the step and their character’s level of wealth increases (ackerman88), exploiting the original glitch.

Glitches also illustrate interrelations between players through power relations and structures resulting from cheating. A popular glitch that has been exploited is called the ‘drop hack,’ which causes another player’s screen to freeze and eliminates that player from the game (ResinLord).  When a second player (as the creature ‘Barbarian’) enters a first player’s field of perception, the battle.net server sends an information packet about the second character to the first (ResinLord). If the second player’s character has many states or ‘modes,’ i.e. skills they’ve built up, when they approach close to the first player’s character the package of information is so large that the server produces a no end-cap and the first player’s computer waits endlessly, freezing the game and leaving the first player’s character vulnerable and open to attack (ResinLord). The glitch occurs due to the transmission of information size, the communication between computers and servers, and the predominance of one character over another. The network privileges one player directly because of the technological equipment and thus the materiality causes the glitch while reinforcing power relations. Glitches subvert the Blizzard authorial presence by functioning in an unintended way, yet they also reconfigure social networks and hierarchies. The glitch deforms capitalist organization while performing a creation of structure, exposing the experiential side of contingency and its ephemerality.

When a second player (as the creature ‘Barbarian’) enters a first player’s field of perception, the battle.net server sends an information packet about the second character to the first (ResinLord). If the second player’s character has many states or ‘modes,’ i.e. skills they’ve built up, when they approach close to the first player’s character the package of information is so large that the server produces a no end-cap and the first player’s computer waits endlessly, freezing the game and leaving the first player’s character vulnerable and open to attack (ResinLord). The glitch occurs due to the transmission of information size, the communication between computers and servers, and the predominance of one character over another. The network privileges one player directly because of the technological equipment and thus the materiality causes the glitch while reinforcing power relations. Glitches subvert the Blizzard authorial presence by functioning in an unintended way, yet they also reconfigure social networks and hierarchies. The glitch deforms capitalist organization while performing a creation of structure, exposing the experiential side of contingency and its ephemerality.

CHANGING THE GAME: PHYSICAL MODIFICATION

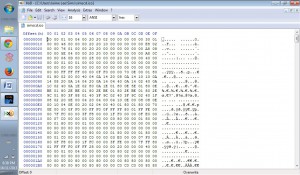

In early game play companies sold devices that could temporarily rewrite the original game’s code to change elements such as the number of lives available or the levels achieved (Consalvo 3 §2 ¶2). The physical modification, a potential ‘glitch’ in original purpose, deforms the game ephemerally while also performing defiance. Another modification uses ‘mod chips’ which are soldered onto the boards of Xboxes or game consoles and are illegal in the United States and other countries, necessitating a black market for mod chip manufacturers and distributors. Mod chips physically deform the board and “show us the current edges of acceptability for the rest of the industry” (Consalvo 3 §6 ¶3), again displaying the network and power hierarchies inherent in commercialist modes of gaming. Glitches from modification uses the object of ‘glitch’ in a different set of statements than the exploitation of glitches; contingency is altered due to the inference of the assemblage’s apparent totality that accompanies manipulation of physical systems. This is further observed in hex editing which uses a hex editor program to expose the internal code of a game that can then be manually modified. A hex edit for Diablo is shown in the following YouTube video where the user locates specific lines of code and rewrites them in order for his character to become more formidable (x51NN3Rx “How to Hex a Character”).  Hex editing is similar to the method of backwards reading employed by McGann and Samuels, providing insight and visualization of the ‘hidden’ mechanisms of the game like the qualities of the Stevens’ poem. “Error sets free the irrational potential and work[s] out the fundamental concepts and forces that bind people and machines” (Krapp 87). Perhaps the paratextual, the companies and mechanisms that arise from the demand of illegal gaming activities, is what enables these errors, the glitches, and therefore reconfigures and makes transparent the machine and the game as well as the relationship between research and gaming cultures. Menkman proposes that glitches destroy meaning (340), while Consalvo discusses the boredom that accompanies cheating in that the game becomes too easy to play ( 3 §6 ¶2). Glitches and boredom function in tandem, whereby perceiving glitches and exploiting them, i.e. cheating, then meaning in a Western signifying mode is ineffectual. Instead of asking what the meaning of a game is if urgency is lost, the question changes to how boredom enables the movement of glitches through social interactions. If the single transcendental signifier (Western notions of ‘meaning’) is eschewed in favor of a multiple organ network structure then polyphonic creation and contingency seem imperative and thus research can include Internet forums, illegal guides and other ‘underground’ digital communities. How does the game’s paratextuality relate to the Internet culture? What are the ways in which we can discuss boredom and loss of meaning in terms of subversion and manipulation in deformative gaming practices?

Hex editing is similar to the method of backwards reading employed by McGann and Samuels, providing insight and visualization of the ‘hidden’ mechanisms of the game like the qualities of the Stevens’ poem. “Error sets free the irrational potential and work[s] out the fundamental concepts and forces that bind people and machines” (Krapp 87). Perhaps the paratextual, the companies and mechanisms that arise from the demand of illegal gaming activities, is what enables these errors, the glitches, and therefore reconfigures and makes transparent the machine and the game as well as the relationship between research and gaming cultures. Menkman proposes that glitches destroy meaning (340), while Consalvo discusses the boredom that accompanies cheating in that the game becomes too easy to play ( 3 §6 ¶2). Glitches and boredom function in tandem, whereby perceiving glitches and exploiting them, i.e. cheating, then meaning in a Western signifying mode is ineffectual. Instead of asking what the meaning of a game is if urgency is lost, the question changes to how boredom enables the movement of glitches through social interactions. If the single transcendental signifier (Western notions of ‘meaning’) is eschewed in favor of a multiple organ network structure then polyphonic creation and contingency seem imperative and thus research can include Internet forums, illegal guides and other ‘underground’ digital communities. How does the game’s paratextuality relate to the Internet culture? What are the ways in which we can discuss boredom and loss of meaning in terms of subversion and manipulation in deformative gaming practices?

EASTER EGGS : TOO EASY?

The Easter egg is a hidden surprise for the video game user which may or may not affect the outcome of the game. The first Easter eggs were illustrations of programmers’ names that would appear if a specific location was scrolled over and resulted in a ‘secret’ communication between programmer and gamer (Consalvo 1 §1 ¶2), however Easter eggs have evolved beyond simple displays to tools for cheating. The Sims, a life simulation game developed by Maxis and published by EA, contains an Easter egg feature that not only changes the player’s strategy but purpose. By pressing the combination [ctrl] + [shift] + [c] a dialogue box on the upper left corner opens and the player then enters a variety of commands which will allow them to increase money, happiness and modify locked features (“Cheat Code Central: The Sims 3”) For example, typing ‘rosebud’ increases the character’s finances by $ 1,000 and the succeeding command of ‘!;’ repeats this gain, making it easy for a player to gain thousands of dollars in a few seconds. The objective of The Sims is to emulate life, a type of simulacra in which the player’s character has a house and family, gains money by going to work and purchases items within the specific budget mimicking a suburban narrative. Subverting the basic objective by illegitimately increasing wealth allows the player to use the game for other purposes and presents a quixotic life. Instead of caring for characters and working to save money, the user can focus on building a mansion or even killing their character. But are Easter eggs the product of commercialist companies or glitches? Can we include them in paratextuality?

By pressing the combination [ctrl] + [shift] + [c] a dialogue box on the upper left corner opens and the player then enters a variety of commands which will allow them to increase money, happiness and modify locked features (“Cheat Code Central: The Sims 3”) For example, typing ‘rosebud’ increases the character’s finances by $ 1,000 and the succeeding command of ‘!;’ repeats this gain, making it easy for a player to gain thousands of dollars in a few seconds. The objective of The Sims is to emulate life, a type of simulacra in which the player’s character has a house and family, gains money by going to work and purchases items within the specific budget mimicking a suburban narrative. Subverting the basic objective by illegitimately increasing wealth allows the player to use the game for other purposes and presents a quixotic life. Instead of caring for characters and working to save money, the user can focus on building a mansion or even killing their character. But are Easter eggs the product of commercialist companies or glitches? Can we include them in paratextuality?

Consalvo argues that the process of finding Easter eggs in the early 1980s is what preceded and thus carved a space for paratextuality (1 §3 ¶5). Nintendo purposely revealed Easter eggs in their magazine Nintendo Power! in order to increase playability and reignite interest in older games (Consalvo 1 §5 ¶1). A former EA employee discussed the purpose of Easter eggs and how they are possibly created. The developer’s knowledge of the Easter egg depends on its impact, if the Easter egg reveals a secret character or skill as in the Nintendo example then it has been vetted by the programmer’s supervisors. However some Easter eggs happen by chance; before a game is released programmers often set parameters for bug testing which include invincibility or unlimited resources. Occasionally these debugging features are not turned off or deleted and thus gamers can either unlock or find these advantages. The developing process becomes pellucid as the Easter eggs illustrate the relationship between software and corporation, retextualizing the game in purpose and functionality.  When entering the rosebud cheat in The Sims a second dialogue box appears on the screen with the words “no such cheat!” yet the money still appears and the cheat in fact does work, inferring that the developers were aware of the cheat, as it recognizes the dialogue box as a place specifically for cheating. Easter eggs do not just set the context for paratextuality; they are paratextual elements themselves, important in video games research. The Easter eggs function much like the index and end notes of a book, providing additional information and credibility, serving as a space in which author/programmer can comment as critic/player. Mark Sample states that “the deformed work is the end, not the means to the end” (“Notes toward a Deformed Humanity” ¶ 13), a declaration that is indicative of the Easter egg’s form. The Easter egg relays information about the user, their intentions, the coding process, the developing and publishing companies, the marketing strategies and the machines themselves. Ultimately more questions about Easter eggs and their relations to glitches arise. Can we apply an adopted digital forensics methodology and formalized approach to investigate how Easter eggs and glitches are developed and relate to layered networks of video games? How do considering Easter eggs as paratextual redefine relationships between glitches and authoritative structures?

When entering the rosebud cheat in The Sims a second dialogue box appears on the screen with the words “no such cheat!” yet the money still appears and the cheat in fact does work, inferring that the developers were aware of the cheat, as it recognizes the dialogue box as a place specifically for cheating. Easter eggs do not just set the context for paratextuality; they are paratextual elements themselves, important in video games research. The Easter eggs function much like the index and end notes of a book, providing additional information and credibility, serving as a space in which author/programmer can comment as critic/player. Mark Sample states that “the deformed work is the end, not the means to the end” (“Notes toward a Deformed Humanity” ¶ 13), a declaration that is indicative of the Easter egg’s form. The Easter egg relays information about the user, their intentions, the coding process, the developing and publishing companies, the marketing strategies and the machines themselves. Ultimately more questions about Easter eggs and their relations to glitches arise. Can we apply an adopted digital forensics methodology and formalized approach to investigate how Easter eggs and glitches are developed and relate to layered networks of video games? How do considering Easter eggs as paratextual redefine relationships between glitches and authoritative structures?

———————————————————————————–

Forms of glitches/cheating in popular culture to be discussed during probe in class:

Nintendo Power! - The Nintendo Magazine with ‘Cheats’

Wreck it Ralph – An animated movie about computer games. Clip 1: Vanellope is a glitch; Clip 2 King Candy uses the Konami Code

Cheat Code Central – A website dedicated to video game cheats

———————————————————————————–

Works Cited

ackerman88. “Diablo glitch/cheat the duplicator glitch.” Youtube. Youtube, 27 Sept. 2009. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

Blizzard North. Diablo II. Blizzard Entertainment, 2000. PC.

“Cheat Code Central: The Sims 3.” Cheat Code Central. CCC, 2013. Web. 15 Nov 2013.

Consalvo, Mia. Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007. Kindle File.

Krapp, Peter. Noise Channels: Glitch and Error in Digital Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011. Print.

Maxis. The Sims. Electronic Arts, 1999. PC.

Menkman, Rosa. “Glitch Studies Manifesto.” Video Vortex Reader II: Moving Images Beyond YouTube. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011. 336-47. Print.

ResinLord. “Godly Diablo II Bugs.” d2jsp. d2jsp.org, 5 Nov. 2008. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

Sample, Mark. “Notes Towards A Deformed Humanities” SAMPLE REALITY. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Nov. 2013. <http://www.samplereality.com/2012/05/02/notes-towards-a-deformed-humanities/>.

Samuels, Lisa, and Jerome McGann. “Deformance and Interpretation.” New Literary History 30.1 (1999): 25–56. Print.

x51NN3Rx “How to Hex a Character.” Youtube. Youtube, 30 June 2013. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.