reBootprobe(sic): Hacking the Alphabet: DJ K-VAS Spins a new Discourse

“O, these eclipses do portend these divisions! fa, sol, la, mi.” – King Lear 1.2.134-35

CHECK IT OUT: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ymjkzSHJZn4&feature=youtu.be

If “Capitalism begins when you / open the Dictionary” (McCaffery 178), then discourse begins when you sing the Alphabet, that national anthem for the English language which we recite in kindergarten alongside the English-colonized nation’s anthem. “Now I know my ABCs” = “Now I know my Ps and Qs.” “M-N-L-O-P,” the class might stutter, to which Teacher scolds “non,” until you get the symbolic order right. Everyone then knows “the” alphabet. Even though everyone must perform (converge) the post-Babelic Ro(o)te Word only in order to deform (diverge) it into its branches, anagrams called “writing”.

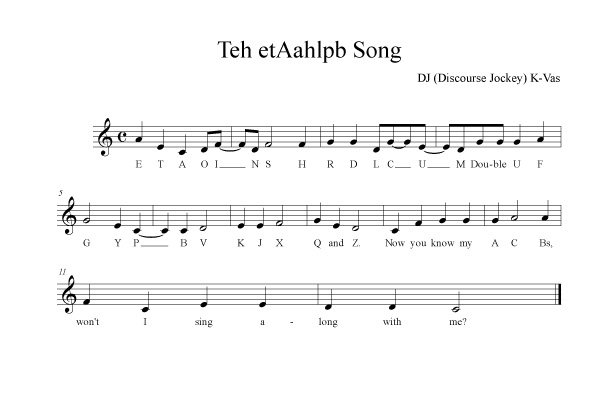

FIGURE 1: The ABC-Alphabet Song

The same is true for music, whose ratios as symbolized in its alphabet of the tone-centric Western scale the alphabet song equally serves to entrench in us. In fact, many of us hear the music first; “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” is a common lullaby. No wonder Zellers once capitalized on the alphabet (“I am Alpha and Omega”) for a commercial jingle. (Cf. the alphabet of brand names.) Another dirge for the “public” domain.

The fact that we memorize the sounds of a spoken language via the sounds of a musical language from which that language wishes us to cloister its own sounds concedes to the inextricability of the two. We cannot talk language without talking sound; and yet our language is content to allow us to talk all the time without talking about it.

It is because of this division that Lisa Samuels and Jerome McGann’s proposal of a “deformance” approach to textual criticism may initially appear alarming to a student trained to worship a text-as-is. Despite poststructural revelations about every reading being a rewriting, “Reading Backward” (4) may somehow seem more blasphemous than all the other inversions that occur in any reading. But from the perspective of music and orality, literature’s forgotten origins, what Samuels and McGann call “deformance” is simply “performance”. Yet they manage to discuss “Interpretation as Performance” (4) without ever mentioning that reading, interpreting, and performing were already concepts long conjoined in music, in which performers “interpret” a piece. Indeed, in many musical practices “Reading Backward” is simply a common compositional and performative technique – in addition to any other number of thematic inversions and transpositions. Hence “Theme and Variations”. (In fact, retrograde performance is even a common trope for the alphabet [song] specifically.)

It is in light of this testament to the alphabet’s symbolic dominance that I have remixed (“deformed”) the alphabet song: to illustrate the contingency of its ordering, information, and the equal importance of sound thereto. The power of remix is in rearticulating what we know, and what do we know more intimately than the first mnemonic tricks by which we were taught to know? It’s about time you learned your ACBs.

For my source text I wanted something bare-bones; I figured something that best foregrounded the tune itself would produce an optimally defamiliarizing variation since it’s the tune that’s implanted in our minds more than any particular performance. YouTube, it turns out, is saturated with variously, often elaborately instrumentated versions, but eventually I came across a kids’ karaoke video-prompter version. I couldn’t resist the idea of having a disordered karaoke text-scan as a glitchy visual.

But for the audio component my initial remix attempt produced disappointment: the karaoke was still far too instrumentated; the backing piano arpeggios made my cut-up too glitchy, too difficult to parse. For an experiment whose efficacy depended upon the compare-and-contrast of pattern recognition, I needed to stick with deformance.

So I simply composed the variation myself into a simple piano line using music notation software (Finale), then exported the MIDI data as a WAV. My variation procedure (same as in my first attempt, my plan all along) was this: I re-ordered each of the song’s letter-note(s) pairs by descending order of English letter frequency. (I contingently pluralize “note[s]” because letters such as “W” take three notes to sing [Figure 2, measure 4].) So, letter “E” (quarter-note A) occurs the most and take’s A’s place, and “Z” (half-note D) still comes last. (“H” and “X” are the other two letters which retain their rank, meaning that the ABC-alphabet does graph for letter frequency but with only 3/26 = 11.5 percent accuracy.)

The next step was to find some vocals to match to my piano. I couldn’t have asked for better than someone’s YouTubed recording of their little girl’s a capella rendition. I stated earlier that the tune is what’s important, rather than a specific performance, but that’s not completely true: a childish timbre engenders the song’s deepest associations. The fact that the girl inevitably would be off-key from my remix, which I composed in C major (“true” to the “original”), would only fuck things up all the better.

I imported all the material into the video-editing software Adobe Premiere Pro, editing the audio there because I realized that I could also still make use of the video portion from the karaoke clip. I blended this together with the video track from the little girl’s video (which I purposely cut somewhat messily, such that the letters on screen sometimes flicker in divergence from what the audio reads), along with some palimpsestic titles, deciding that if I couldn’t glitch the audio, I could at least match my audio deformance with a pretty glitchy-looking video. (I suppose I’ve glitched/deformed the deformance-glitching binary, in that sense, if there was one.)

I then decided to add a “second movement”: the song recapitulated into a forty-voice canon (a form all the more appropriate as the term “rote” roots from the Latin rota – a form of round-singing). This was cutely prompted by what I did for the song’s fourteen-note lyrical coda (alterations in bold): “Now you know my A C Bs, / won’t I sing along with me?” The “you” emphasizes the listener in their process of relearning “ABCs” by frequency (becoming the “ETAs” in toto, the “ACBs” by this sample), and the “I sing along with me” signifying not only likewise the remix process whereby, as Barthes would say, every reading is always already a re-reading, as well as signifying the re-othering of the little girl’s identity, but this subsequent movement, in which the song now will literally sing along with itself. Appropriately, after each “double U” of each added iteration a new iteration of the song enters (doubles its/yours/the little girl’s “you”), and this grows until there are forty voices/songs. Forty because there are forty notes in total in the song, such that by the fortieth iteration we are hearing every letter-note(s) pair pronounced with one instance of every other, such that in theory one can extract from that mess any other alphabetical order one wants to. It also, of course, makes manifest the letters’ frequency in two other senses: one, as the representation of frequency now gains a vertical as well as horizontal audio dimension, and two, as the many voices of the many children repeating themselves into the symbolic order – until, of course (a third sense), they ultimately rupture into the real of those other kinds of frequencies, measured in Hertz. As for the video tracks, I palimpsested all those too, producing a glitchy aesthetic, which is truly glitchy insofar as the end result was not wholly predictable to me. (It was either this – achieve the RAM-bunctious eighty tracks of audio + video – or stop whenever my software or computer glitched/crashed for real on the way there [and record/incorporate the result]. Alas, “What actually happens when a glitch occurs is unknown”, and if it’s predictable or premeditated it’s not a true glitch [Menkman 9].) And so, here you have it: the ETA-alphabet song!

My chief motivation for this variation approach was to attempt a serious example of musical infographism which as such would question the information encoded by the ABC-alphabet. I mentioned at the beginning the tone-centricity of the Western scale. While in the ETA-alphabet song (the first movement, at least) this tone-centricity is still inevitably upheld because of the song’s being in C major, some of the tonic cadential structures present in the ABC version are disrupted by the ETA: we no longer get the neat melodically and rhythmically symmetrical phrasings (Fig. 1) ideal for encoding arborescent long-term memory (see Deleuze and Guattari 16). Especially notice how the redistribution of the ABC song’s sole sequence of eighth-note words (“L”-“M”-“N”-“O”) produces uneven, less predictable, less structured, less military rhythms – i.e. syncopations: the tied notes across measures 1-2, 3-4, and 5-6 (Fig. 2).

But the ETA-alphabet also raises even more serious questions about ideology and pedagogy in regards to language. First, what does it say that the infrequency of “Z” provided Shakespeare the following insult: “Thou whoreson zed! thou unnecessary letter!” (King Lear 2.2.60)? Clearly, the perceptions of even words and letters are ideological. What perceptions, therefore, might a more alphabetically explicit ranking of letters alter or exacerbate (regardless of Scrabble scoring knowledge)? Second, there’s nothing to say that learning the alphabet song is the best way of learning the alphabet or of learning linguistic operations in general. This home-schooling program, for example, recommends teaching children the sounds letters make before teaching the names of the letters. Learning the names of letters is less useful and not really the point, causing unnecessary confusion for children; moreover, the program argues, teaching children sounds rather than language-specific names encourages polylingualism, discourages language-isolationism! Similarly, one must wonder about the potential advantages of grouping letters alphabetically by their categories (e.g. closely related consonants grouped together; the ETA actually happens to do this with “p” and “b”), or of teaching children the International Phonetic Alphabet, or multiple alphabets and alphabet songs…..

We really ought to think on these things, next time we recite the global lingua franca’s international lullaby.

Works Cited

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. “Introduction: Rhizome.” A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Massumi, Brian. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. 3-25. Print.

McCaffery, Steve. “Lyric’s Larynx.” North of Intention: Critical Writings 1973-1986. New York: Roofbooks, 2000. 178-84. Print.

Menkman, Rosa. “Glitch Studies Manifesto.” Video Vortex Reader II: Moving Images Beyond YouTube. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011. 336-47

Samuels, Lisa, and Jerome McGann. “Deformance and Interpretation.” New Literary History 30.1 (1999): 25–56.