Probe: Kayaking with the Critics

If the digital humanities have been absent in what Liu calls “cultural criticism”, then what criticism or “critique” actually entails in the postmodern age should be subjected to analysis so as to ascertain what exactly is involved in the critical process. For Latour, at least in 2003, a crisis of confidence in his ongoing critical pursuits encouraged a self-assessment – a recognition of the possibility that the theory and practice of his methodology had been appropriated by socio-political forces that maintained diametrically opposed ideological stances vis a vis the transformative cultural instance of 9/11. Not that the events of 9/11 themselves had sent the populace in search of a critical method by which they could challenge the geo-political proclamations of certitude related to the Fukiyomian 1992 declaration regarding the end of history or the Huntingtonian (via Bernard Lewis) insistence on the incompatibility of civilizations. The climate of challenge in relation to established “facts” regarding scientific, societal, political and cultural growth has a more sustained history – a history that involves the modernist yearning for the “new” and a particular affinity with the events of May 1968. Latour, however, embraces the militaristic jargon of the post-9/11 atmosphere in his essay “Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern”, and proceeds to critique his critiquing methods. What is surprising in this transcribed lecture (and it is important to acknowledge that this was a public lecture requiring a performative delivery) is the tone that suggests that Latour is somewhat shocked that his methodology has been appropriated and manipulated by ideologues who are intent on “instant revisionism” in accordance with a specific agenda. What is troubling is Latour’s egocentric sense of shame – that he is responsible for “let[ing] the virus of critique out of the confines of their laboratories and cannot do anything now to limit its deleterious effects; it mutates now, gnawing everything up, even the vessels in which it is contained” (Latour 2004, 231). The “mad scientist” analogy and employed language is dramatic and obviously performative, – undoubtedly latour is exaggerating for effect. Nevertheless, the premise that postmodernist forms of critique, including the revelation of the “social construction of scientific facts”, have uniquely transformed the social and cultural landscape in such a way as to allow for the “bad guys” to undermine and “destroy hard-won evidence that could destroy our lives” (Latour 2004, 227) is questionable. It can be argued that the particulars of Latour’s methodology of critique are not unique and are not responsible for the advent of patronizing conspiracy theory proponents.

Latour’s insightful exposition on the relationship between “matters of fact” and “matters of concern” relates to his discussion regarding the “conditions that made them [matters of fact] possible” (Latour 2004, 231). What ensues is an understanding that the matter of fact – that which is a “primary quality … real, material, without value and goals and only known through totally unknown conduits” (Latour 2008, 36) – evolves into a matter of concern once “you add to it its whole scenography, much like you would do by shifting your attention from the stage to the whole machinery of a theatre” (Latour 2008, 39). What Latour is doing here is attempting to suspend the “bifurcation of nature” by removing the distinction between Heidegger’s separated “object” (coke can) and “thing” (handmade jug). In essence this attempt by Latour to erase this distinction transforms the matter of fact into a viable component of a whole contained within the matter of concern. The thing becomes this whole: “A thing is, in one sense, an object out there and, in another sense, an issue very much in there, at any rate, a gathering. To use the term I introduced earlier now more precisely, the same word thing designates matters of fact and matters of concern” (Latour 2004, 233). Latour maintains that the matter of fact remains in play and is engaged in a symbiotic relationship with matters of concern that involves a continual ebb and flow between the two:

Instead of simply being there, matters of fact begin to look different, to render a different sound, they start to move in all directions, they overflow their boundaries, they include a complete set of new actors, they reveal the fragile envelopes in which they are housed. Instead of “being there whether you like it or not” they still have to be there, yes (this is one of the huge differences), they have to be liked, appreciated, tasted, experimented upon, mounted, prepared, put to the test. (Latour 2008, 39)

For Latour, Heidegger’s bias prevented him from being able to understand the conflation of this gathering: “Heidegger’s mistake is not to have treated the jug too well, but to have traced a dichotomy between Gegenstand and Thing that was justified by nothing except the crassest of prejudices” (Latour 2004, 234).

This re-appropriation of the object (matter of fact) away from “critical barbarity” is the overarching concern for Latour. His review of the critical landscape challenges the continued binary associations regarding the fact position and the fairy position of the object and exposes the bias of the critics: “We explain the objects we don’t approve of by treating them as fetishes; we account for behaviors we don’t like by discipline whose makeup we don’t examine; and we concentrate our passionate interest on only those things that are for us worthwhile matters of concern” (Latour 2004, 241). Here lies the problem that provoked Latour’s exaggerated sense of culpability at the beginning of his essay/lecture. Critics are fixated on a particular interest (their own) and are stubbornly unwilling to engage in a “gathering” by which the matters of fact can be incorporated within the “whole” of the critical enterprise and not relegated to a binary opposition. What Latour suggests is that critics need to reassess their methods and approaches so they no longer have to “live in the phantasmagoria of divided experience, having to choose between meaning without reality and reality without meaning” (Latour 2008, 26) – the two riverbanks that correspond to the bifurcation of nature. What is exposed here is that, despite the trajectory towards a breakdown in the multiplicity of distinctions of the “old” school of criticism, postmodern critique, so Latour seems to be suggesting, still maintains an “othering” component and that has allowed for the “bad guys” to employ these techniques in subjective and pseudo-critical ways.

But is this really the case? Is the problem that disturbs Latour the fault and responsibility of the specifics of the critical practices employed by today’s academics? Has there actually been as great a gap between the matters of fact and the matters of concern that Latour is suggesting? These questions pertain to the distinctive and debated role of the critic. Latour argues that “a certain form of critical spirit has sent us down the wrong path” (Latour 2004, 231) and this has a direct correlation to the concerns expressed regarding “prejudices” at the beginning of his essay. The philosophical discussion regarding the methodology of critical approaches to matters of fact emanate from a concern with the lack of any critical “sure ground” that leaves the path open for conceivably outrageous claims in the name of critical exegesis. Is there a suggestion, by the end of the essay, that a “sure ground” is obtainable? Is a recognized and mutually accepted foundation of critical positioning necessary? Latour is just problematizing here – he doesn’t pretend to have a definitive answer. But he does have a strong sense of the critic’s role:

The critic is not the one who debunks, but the one who assembles. The critic is not the one who lifts the rugs from under the feet of the na ̈ıve believers, but the one who offers the participants arenas in which to gather. The critic is not the one who alternates haphazardly be- tween antifetishism and positivism like the drunk iconoclast drawn by Goya, but the one for whom, if something is constructed, then it means it is fragile and thus in great need of care and caution. (Latour 2004, 246)

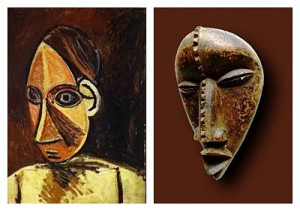

The critic is not to pass judgment but to elucidate and reveal the multiplicity of possibilities contained within any given object (or gathering, or matters of concern etc.). This has been the designated role of the critic throughout the twentieth Century. Modernism produced the multifaceted critic – the critic/scholar/artist – a critic who could draw on a wealth of knowledge and a diversity of expertise facilitating the daunting task of attempting to excavate the complexity and density of the modernist artistic pursuit. Modernism saw an explosion of diversity regarding the subject matter and objects of creative developments. Those matters of fact were embraced by the twentieth century artist and easily slipped through the borders/barriers that defined Whitehead’s bifurcation of nature. The artist was (is) a critic drawing on the plentitude of post enlightenment possibilities revealed by the secularization of the entirety of concerned fields contained in the humanities. The historical, political sociological, psychological, economic etc. were critiqued and absorbed into a modernist “gathering” fueled by utopian ideology that generated an exploratory fervor that insisted on “making it new”. William Carlos Williams fuses Man and City into a new identity – an “interpenetration” that proclaims: “no ideas but in things” (Williams 4-6). What is this if not a creation and a critique? Pound’s Cantos not only insist on a rhizomatic reading, but his work as a critic (ABC of Reading) utilizes typographic innovations augmenting the “lesson” with a plea to reach beyond the classic tradition and absorb the visual (visionary) reading experience. The modernist experience tore down barriers revealing the latent networks that had been hidden under the oppression of institutional (religious and political) rule. These networks led artists and critics alike to explore the cultural diversity of the age and brought African primitive sculpture to the Paris avant-garde

and initiated the proliferation of modernist collage techniques that assembled seemingly incompatible objects, blending high and low cultural icons and everything in between.

What is this if not a “gathering” – what Latour, in his Spinoza lectures, refers to as a “kayaking” down the river separating the two riverbanks of the bifurcation of nature? (Latour 2008, 13-14). Whether it is John Cage’s engagement with Joyce (Roaratorio),

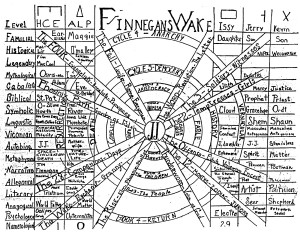

or Moholy-Nagy’s visual representation of the Wake

or Iain Sinclair’s circulatory turn around London via the M25 (London Orbital),

artists from the pre and post 1968 “moment” are both creators and critics intent on challenging the norm and utilizing all the technologies and tools at their disposal to navigate the rapids caused by the mixing sands and tumbling rocks of the riverbanks.

Liu’s ambition to bring digital humanities beyond the “purely technical concerns of implementation” and into the forefront of cultural criticism within the humanities can be (is) realized once the necessity and value of the tools of implementation are more fully recognized and adopted by academics working in the Humanities. These tools are radically changing the research methods and abilities in such areas as Biblical studies. Access to interactive websites related to the discoveries at Nag Hammadi and Qumran have encouraged and facilitated the continued research among the proponents of the “New Perspective” in Pauline studies and the ensuing criticism/scholarship (including the input of continental philosophers such as Badiou, Agamben and Zizek) has forced a complete reassessment of the Lutheran monopolizing critique of Paul and has brought together the previously opposing and entrenched camps of Second Temple Judaic Studies and Early Christian scholars – they have moved off the riverbanks and are now kayaking (gathering) together, unveiling new possibilities in their cultural exchanges (and enabling my own research regarding the Pauline influence on modern poetics). The tools of the digital humanities are already relevant to cultural criticism per se. As Liu acknowledges towards the end of his essay, it is the Humanities in general that must struggle with outside perceptions that marginalize these fields – we are in an age of “practicality” and the three minute sound bite – an age that has little patience for the rigorous intellectualism that is necessary in order to elucidate the complexities contained in Finnegans Wake or the intricacies of the Obama Health Care Plan.

Perhaps the “bad guys” of Latour’s derision are not appropriating an independent critical stance in response to postmodern critical methodology; perhaps their actions are related more to the accumulated (dis)information dispensing technological tools available (social networks, blogs etc.) and the continued failure of political systems to earn trust and deliver on the initial utopian hopes suggested as far back as the enlightenment. Other than the relatively brief intervention of the “new critics”, criticism and critiques have been cognizant of a multiplicity of networks and discourses that shape the cultural landscape. Pre-1968 modernism/modernists sought to reshape this landscape – to mold it into a positive force. Post-1968 (post)modernism/modernists have despaired at the percieved failure of their predecessors and have since been seemingly intent on reshaping the discussion/discourse in an attempt to alter the status quo. The critic in both epochs has played the same role – elucidating and uncovering relations while refining their methodologies to accommodate the influx of new intellectual understandings. But that role has rarely been destructive or culpable in the violence of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The critic/artist has sought harmony amidst the continued confusion caused by the endless “swirl” of the exponentially expanding number of networks – the critic works in tandem with the artist/creator/object helping to sift through the weight of the symbiotic fusion of the matters of fact and the matters of concern seeking a reconciliation that will reveal a potentiality for a greater cultural “gathering”. The problem is that no one wants to listen – most people (due in part to the expediency of technological innovations in communications and information gathering and the loss of intellectual rigor at the expense of that expediency) want quick and easy answers that conform to their already established riverbank view – and they want someone to blame for the unrealized utopia – often that someone is attempting to “right” their kayak in a department somewhere in the humanities.

Works cited:

Latour, Bruno. “Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern.” Critical Inquiry 30 (Winter 2004): 225–48.

__________. What is the style of Matters of Concern? Amsterdam: Department of Philosophy of the University of Amsterdam. 2008. bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/97-SPINOZA-GB.pdf

Liu, Alan. “Where is Cultural Criticism in the Digital Humanities?” Debates in the Digital Humanities. Ed. Matthew K. Gold. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012. 490–509. http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/20.

Williams, William Carlos. Paterson. New York: New Direction. 1992