The Last Probe: Additive Critical Gestures

VLADIMIR: Sewer-rat!

ESTRAGON: Curate!

VLADIMIR: Cretin! ESTRAGON: (with finality). Crritic!

VLADIMIR: Oh!

He wilts, vanquished, and turns away.

Q) Are we stuck in a critical trap?

A) (Sardonic laughter)

Q) Seriously, are we?

A) (Rolls eyes)

With God, The Author, The Subject and The Text all dead, the critical landscape is starting to look like one of Moretti’s Hamlet diagrams. At least there are still digital humanists to organize the corp(o)ses, and distant reading archivologists to design the neatly ordered plots where texts can be found amongst their family resemblances. On a map, near the bottom of a tree, it is written: Here lies Early Detective Fiction, killed by subtler clues. But will the texts lie silent in their neatly ordered graves? Or will there be ghosts in the machine? Will there be ghosts of the Ghost of Tom Joad, indignantly speaking out for the individual texts that have no voice?

Unlikely, according to Alan Liu:

The relevant text is no longer the New Critical “poem [text] itself” but instead the digital humanities archive, corpus, or network—a situation aggravated even further because block quotations serving as a middle ground for fluid movement between close and distant reading are disappearing from view (Liu).

Individual texts, Liu argues, are no longer significant. Rather, the archive, corpus or network is the significant matter of concern for digital humanities. His logic, undeniable really, is that text analysis focuses on a microlevel and is mapped on a (seriously massive) macrolevel. The middle ground comprised of individual texts, or even groups of individual texts, is not applicable to this model of DH. Their only possible survival method is to perform lexical duties in larger para-textual networks, similar to the role they play in Barthes’ S/Z.

The problems with lexical synecdochism are numerous, and I’m not too keen on using this loophole to save texts from the digital abyss. If all we get to keep from Hamlet is, “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark”, I say “not to be”. Landow’s technologically antiquated yet historically relevant Hypertext (circa 1992), describes the early 1990’s hyper-textual paradigm shift, noting that the originators of this movement aren’t all technological theorists like Theodor Nelson and Andries Van Dam, but also literary theorists like Barthes and Derrida:

Barthes describes the ideal textuality that precisely matches that which has come to be called computer hypertext—text composed of blocks of words (or images) linked electronically by multiple paths, chains or trails in an open-ended, perpetually unfinished textuality described by terms link, node, network, web and path. (Landow 3)

It may be an cliché observation, but it is relevant to point out that the network superstructures performing the annihilation of singular texts seem to be fractal images of their antiquated predecessors . But hasn’t the interest in texts always adhered to patterns within networks? And, moreover, haven’t blocks of texts, acting within seemingly closed textual networks (poems/books ect) always actually existed within larger global networks? Are Literature, Philosophy, History, Politics anything other than globally integrated networks?

In Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern, Latour asks, “Is it really possible to transform the critical urge in the ethos of someone who adds reality to matters of fact and not subtract reality?” (Latour 232). One of the ways to produce additive criticism, which Latour and Liu both point to, is to integrate scientific practices within the humanities, digital and otherwise. This shift is largely what we’ve been studying this semester. By observing scientific methods, techniques and philosophies, we have seen a series of critical analyses and techniques that attempt to circumvent the debilitating rhetorical dogmatism inherent within hermeneutic deconstructionism and other interpretive based literary critiques. Latour sees this possibility as additive, and I think we can all stand to live within this critically framed worldview.

Starting in January, Latour is responsible for a MOOC called Scientific Humanities. The course website claims that it will provide students with the “extension of interpretative skills to the discoveries made by science and to technical innovations. The course will equip future citizens with the means to be at ease with many issues that straddle the distinctions between science, morality, politics and society.” This sounds like a great course, but if we read (ahhhhhhhhhhh) closely, there is no mention of aesthetics. Latour is really selling Scientific Social Sciences, which not only sounds redundant, but is not an original product (think Plato’s Republic, or more recently Gall’s seminal text of 1809, The Anatomy and Physiology of the Nervous System in General, and of the Brain in Particular, with Observations upon the possibility of ascertaining the several Intellectual and Moral Dispositions of Man and Animal, by the configuration of their Heads). I’m not suggesting that Latour is selling us a bridge, or that the new scientific social sciences aren’t more scientific then phrenology, only think we should any claims representing the final humanities solution with a grain of sodium chloride (NaCl).

Bruno Latour’s Scientific Humanities

My main point is this: as scientific discourse merges with the humanities, aesthetics should be taken into consideration, or the merger will turn out to be a massacre (and it will be boring to watch). Perhaps ironically, the best reason I can recommend that aesthetics maintain a seat at Liu’s proverbial table is that aesthetic projects provide critiques without explanation. While aesthetic projects are not always theoretically accessible, they are inherently critical. Further, the types of critiques available aesthetically are not always available to critical theorists or scientists.

Aesthetic projects are able to present uniquely aesthetic critiques because they do not have to make scientific truth claims. And from the social interstice of unreality, statements can be made that might otherwise not come to fruition. In an earlier probe I tried to suggest that Foucault’s critique of history was already being formulated by narrative experimentation in the early 60′s. Can we not also say that Finnegans Wake is legitimate critique within the discourse of linguistics? Or that Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu is an essential critique in the discourse of consciousness? The latter text is so influential within French theory that it would maintain a preeminent position on an evolutionary tree depicting the readings on our syllabus.

Aesthetic projects are also, like branches of applied science, critically additive within their own discursive communities. Beckett, for instance, writes critically on both Joyce and Proust, but I would argue his best critical addition to the discourse surrounding each author’s work is the stark non-referential style deployed in his own dramatic works. Further, I would argue that Joyce and Proust’s aesthetic projects provide essential analysis on the work of their own forbearers, Flaubert, for example. What differentiates aesthetic critiques from the explanatory critiques Latour bemoans, is that they are additive and not subtractive. You can read Joyce and say, “wow I see what he’s doing with the in the head thing, its like Flaubert, but kind of more in there,” but you don’t have to throw Sentimental Education in the garbage afterwards. You can read it again, with pleasure. What’s disheartening about interpretive literary criticism and critical theory, which is directly tied to the political economy of institutionalized power structures that churn out academic papers ad infinitum, so we can theoretically have jobs, is that the urge/pressure to continually re-explain static text-objects lends itself to theoretical cannibalism. If Theorist A proves that the correct interpretation of Text X is Explanation Y, what do we do when Theorist B proves that Theorist A’s Explanation Y is absolutely incorrect, and that the correct interpretation of Text X is obviously Explanation Z. And what of the up and coming Theorist C? In this process, we have read and discarded Y and A, B and Z’s days are numbered, and C+N(ew theory) is probably going to destroy whatever’s left of X.

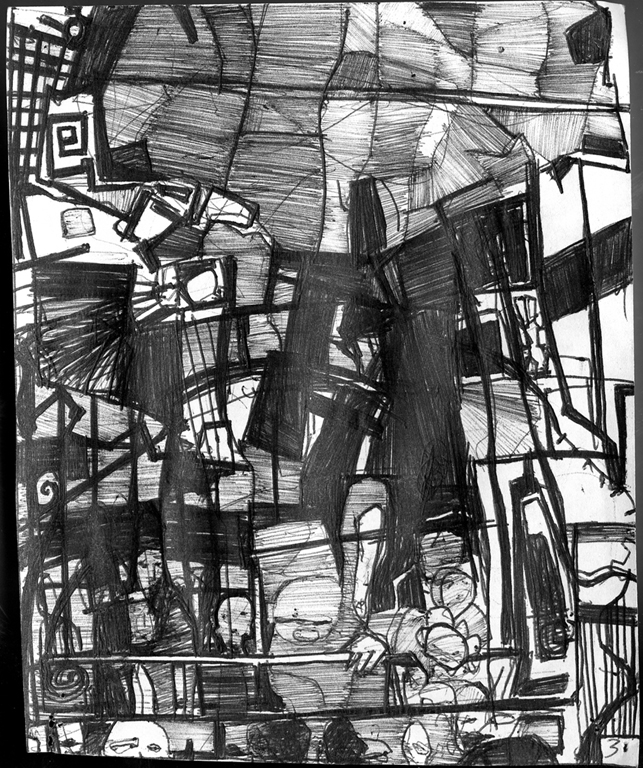

But what of a different paradigm? Imagine a text. Now read the text and make an illustration for every page. This is Zak Smith’s addition to the critical apparatus surrounding the Thomas Pynchon’s 760 page Gravity’s Rainbow:

Zak Smith’s Illustrations For Each Page of Gravity’s Rainbow

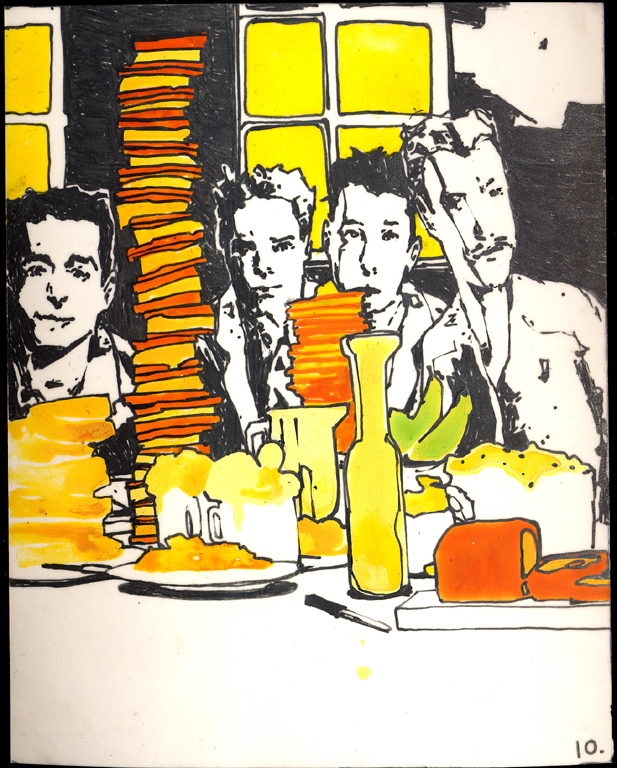

Here are some selections from Smith’s illustrations.

A screaming comes across the sky…Above him lift girders…the carriage, which is built on several levels…drunks, old veterans…hustlers…derelicts, exhausted women with more children…

…banana omelets, banana sandwiches…tall cruets of pale banana syrup to pour oozing over banana waffles…

And highly relevant to this class…

Terri Saul: Did you make the illustrations as a slow and methodical way of reading Gravity’s Rainbow? Or, did you read GR first, and decide to use it as a tool to make your work spin off in a new direction?

Zak Smith: I read GR years before I did the project—but I realized that a lot of the ideas in it—the density, the intricacy, the mishmash of styles and moods, the sort-of-sci-fi-but-sort-of-real-life thing—were all things I had been trying to get in the other work I’d been doing, So, rather than using the GR piece to make my work spin off in a new direction, it was more like trying to use the GR piece to pinpoint some ideas that had been flitting around in there all along. (Quarterly Conversation)

As Smith points out, his work, while certainly interpretive, does not solely constitute an interpretation. Smith’s aesthetic practice blends interpretive analysis with critical judgement in order to materially render a new vision of Pynchon’s text that doesn’t subtract from, but adds to the critical discourse.

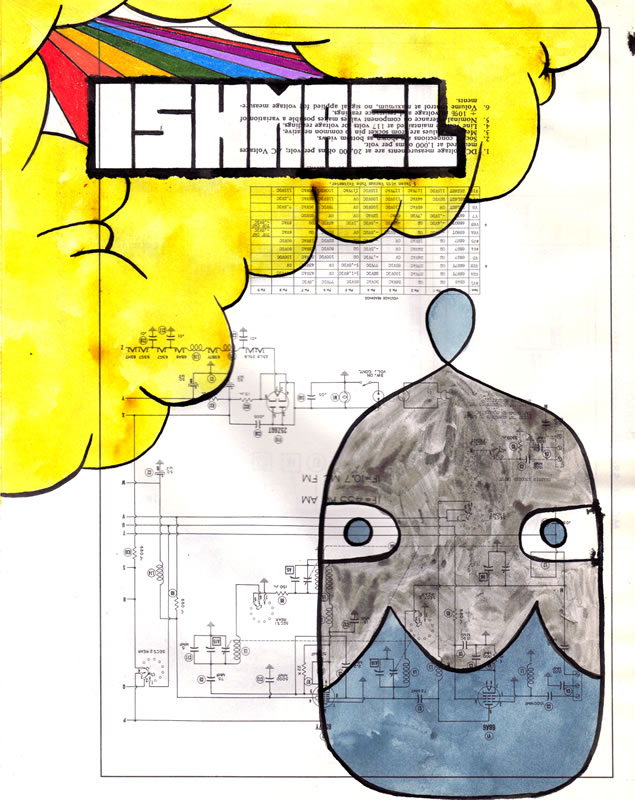

There are other similar projects. In 2009, Matt Kish began an epic journey of his own, which found Kish creating one painting per day for 552 consecutive days relating to Herman Melville’s 552 page Moby Dick.

Moby-Dick in Pictures: One Drawing for Every Page

‘Call me Ishmael’

Colored pencil and ink on found paper, August 5, 2009

‘Hearing the tremendous rush of the sea-crashing boat, the whale wheeled round to present his blank forehead at bay; but in that evolution, catching sight of the nearing black hull of the ship; seemingly seeing in it the source of all his persecutions; bethinking it – it may be – a larger and nobler foe; of a sudden, he bore down upon its advancing prow, smiting his jaws amid fiery showers of foam’

Ink on watercolor paper, January 22, 2011

There are also installations of similar natures, including A Failed Entertainment: Selections from the Filmography of James O. Incandenza. The exhibition, organized by Sam Ekwurtzel, opened at Columbia University’s LeRoy Neiman Gallery, presenting 22 instillations adapted from of James O. Incandenza’s fictional filmography (found in a single footnote from Infinite Jest).

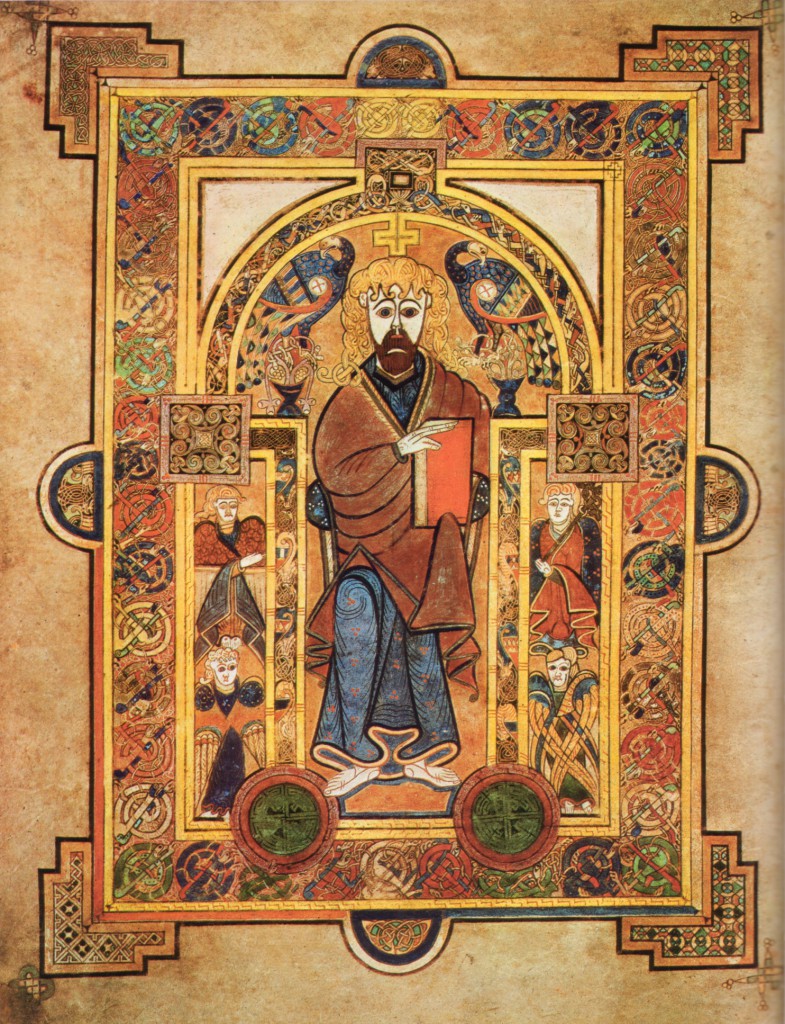

But none of this is new. You can’t write a dissertation based on the fascinating discovery that artists use texts for inspiration. Art has accompanied books since the beginning of books.

In fact, text was art before the pyramids!

All this to say, in response to Latour’s request, I would suggest there are at least two additive critical formulas. One is to apply scientific techniques to the critical analysis of objects, including but not limited to the circulation and articulation of objects within networks. And the other is through the actualization of aesthetic practices, by creating new objects which are not reflexively but intrinsically critical by virtue of their immediately relational status within previously existing aesthetic networks. And as such, I ask that when the divide between arts and science is finally bridged, that we don’t make aesthetics…

Works Cited:

Landow, George. Hypertext: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press, 1992. Print.

Liu, Alan. “Where is Cultural Criticism in the Digital Humanities?” Debates in the Digital Humanities. Ed. Matthew K. Gold. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012. 490-509. http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/texts/20

Latour, Bruno. “Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern.“ Critical Inquiry 30 (Winter 2004): 225-48.Smith, Zac and Terri Saul. Interview. Quarterly Conversation. http://quarterlyconversation.com/the-zak-smith-interview. Online. Accessed Nov 22, 2013.