Mapping the Fictional

As my dissertation slowly begins to take a hazy shape (somewhere far off in the future, it sometimes feels), I’ve been turning my thinking and energy towards the geographic. There are all sorts of ways to assert this descriptor that interest me and stimulate thinking about media. There’s imaginary geography (Said’s concept of those perceived spaces created by narrative, discourses, image and sound), fictional geography and cartography (think of the richly detailed worlds of fantasy novels and the maps found on their inside covers), virtual geography (Batty’s idea of simulated environments that algorithmically combine real geographic traits from mapped spaces and invented details), and the city symphonies of classic and contemporary cinema (those experimental documentaries that capture urban life, from Man With a Movie Camera and Berlin: Symphony of a Great City to spiritual inheritors of the genre like Baraka and Toronto Tempo). The list goes on and on, and once you get into conceptual geographies like information visualizations, the field explodes. What really piques my interest though is thinking about the geographic when it comes to transmedia and pop culture assemblages.

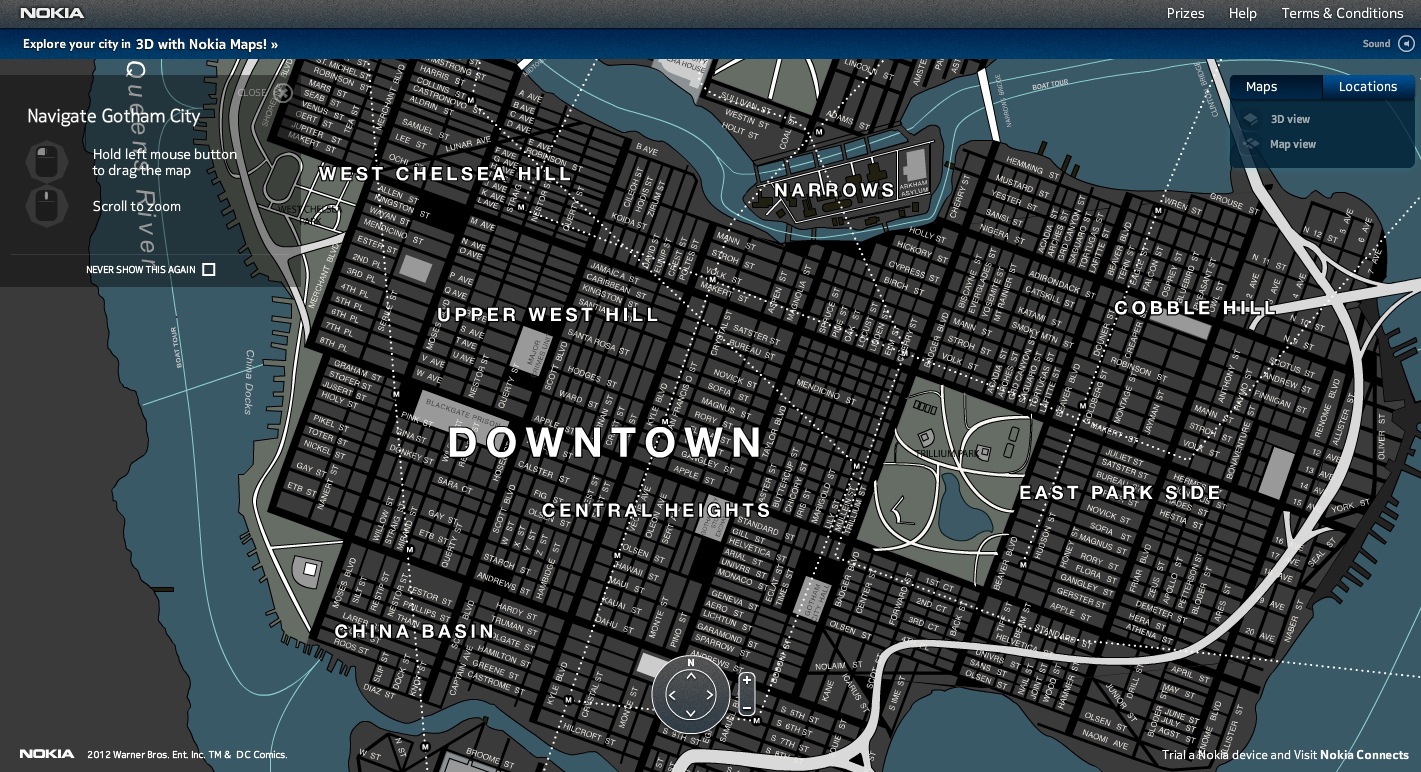

With digital record-keeping and transmedia franchising we’re seeing fictional geography treated in a way it’s never been treated before. The details of an imaginary city’s geography, for example, used to be exclusively the realm of the die-harder, the kind of reader or audience member who questions the redesign of the city’s skyline or the relocation of a building for narrative convenience. In the old paradigm, the majority of media consumers seem to have paid little mind to the inconsistent randomly generated landscape of games like Arena or that Godzilla might be seen smashing the exact same building three times in one movie. Now, digital networking allows transmedia to more easily establish aesthetic and geographic consistency across a vast narrative disseminated through multiple media.

The island of Lost is a great example. For a fake place that literally moved and jumped around the ocean over time, the producers of the show (and books and websites and games and merchandise) put a great deal of work into maintaining a steady map of the island that clearly charted the distance from one landmark to another. Was this necessary to please anyone beyond the die-hard fans? Probably not, but the creators of Lost wanted to create a sense of realness and possibility for the story’s audience, and consequently made a map for consultation whenever any branch of the creative team looked to script an episode or produce an offshoot website or product. Though the story would eventually posit the idea of the island as a metaphor or ethereal space, physicality of the mapped island was the foundation on which the entire story was constructed.

In the next year, my responsibilities with IMMERSe expand slightly to cover the grounds of my own research initiative. I’ve been tasked with building my own little research team around questions of fictional geography and producing some knowledge. Just what this entails is still in development, but I know I’d like to get a few publications done, and maybe build an annotated bibliography for researchers interested in the topic in the future. As it stands, I’ve already collaborated with Skot Deeming to put together a panel CFP for next year’s SCMS and begun my research into fictional geography in earnest. The next step, I think, will be to start collecting maps–especially from games.