The Carpenters of BFC

This last week (and then some) was characterized largely by resource gathering. This was heavily streamlined by way of the monster farms in the adorably named “Farmer’s Market”. Gathering Glowstone Dust was simple enough, with any treacherous trips to the Nether rendered unnecessary and replaced by the simple task of whacking some respawning ghosts over and over. Incidentally, it gave me a chance to try out a plethora of weapons, including the ever-alluring polearm – you can throw it, and it is awesome.

But I digress – let’s talk about BFC. My colleagues have been constructing the building itself by dual-clienting Minecraft and using the BFC on the vanilla server as blueprints of a sort – though, in reality, it’s more akin to running between a completed building and an unfinished one, building the latter in the likeness of the former. This would probably be incredibly inefficient for actual construction workers, but in our virtual landscape, it’s allowed for the most productivity and only a few miscalculations.

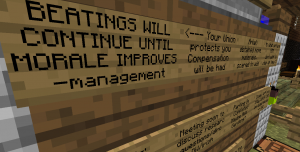

The two buildings have already diverged – either stylistically (the alloy wire parking dividers, the statues, etc.) or mechanically (the chicken cooker itself following a rather different model found on YouTube than the one used in the original BFC), but it’s still unmistakably a BFC. We have the giant, glowing letters sitting above our building site, we work under the oppressive gaze of the giant chicken sticking out of the roof, and we have the… hellish wall of fire surrounding the premises. So what if there’s a little change here or there? A McDonald’s will be instantly recognizable so long as the ubiquitous golden ‘M’ is present, as well as some depiction of Ronald McDonald and sometimes the less-than-sanitary indoor playground for children. Each institution will vary in some slight way or another, but as we live in a culture of icons, a few visual cues will often be enough to establish familiarity – and that’s sort of what building a franchise is all about. Why take a chance on new food when you can kill yourself slowly with the warm, familiar comforts of BFC’s mass-produced autonomously-cooked chicken? (Yes, I realize I should not be involved in marketing of any sort.)

Back to the act of building itself, though: let’s talk about carpentry, now. Specifically, Ian Bogost’s idea of carpentry: the philosophical act of making things. What we, as a team, are doing, is research. Our research does not take on the conventional form of toiling through books and scholarly articles and wasting away in a library – no, Dr. Wershler is infinitely more merciful. We build on a Minecraft server, collecting the appropriate blocks and placing them, one by one, in the shape of a building. Bogost would already consider the more conventional approach to research (or at least the documentation of it) carpentry, but I like to think he’d be particularly tickled by this brand of research. Our research is going to leave something tangible behind – at least as tangible as a virtual fast-food restaurant can be.

To quote Bogost from his book, Alien Phenomenology, “philosophical carpentry is built with philosophy in mind: it may serve myriad other productive and aesthetic purposes, breaking with its origins and entering into dissemination like anything else, but it’s first constructed as a theory, or an experiment, or a question – one that can be operated” (100). What we are doing is philosophical carpentry. We were not simply hired to join the TAG server and build a self-cooking chicken restaurant for the convenience of the other players (unless we were, but I’ll leave conspiracy theories for another post); our main objective wasn’t just to acquire an ungodly amount of cooked chicken – we were building this with philosophical ideas in mind. The idea of a ‘question that can be operated’ is especially interesting – the BFC building is not just a building, it is not just a collection of Minecraft data, it’s not just a player facility: It is also an inquiry, or many inquiries. It (and its construction) asks us how a virtual commons functions, how a commons can expand, how people come together and industrialize, and a number of other interesting questions. “Philosophy is a practice as much as a theory”, Bogost tells us (92). Our research does not begin after we’ve logged out of Minecraft and begun collecting our thoughts for these weekposts – our research is the construction; our theory is intertwined with our practice.

Finally, I’d like to follow up on some of the questions I posed last week. Being more acclimated to the server and its plethora of oddities, I’m no longer quite so overwhelmed, and that’s something worth examining. There’s definitely a direct correlation between the time one spends in the commons and just how comfortably they reside in them. Now that I’ve directly contributed to the enhancing of the commons, they feel more like just that – commons – as opposed to, say, the private property of strangers that I’m treading upon. Eric Raymond, in his paper ‘The Magic Cauldron’, likens the commons to open-source software, but makes the distinction that open-source software increases in value as more and more people contribute to it, as opposed to decreases. The commons – in this case, the ‘open-source software’ – benefits from the more cattle that graze upon it, rather than the other way around. This disparity begs the question: has our addition to the server enhanced it or degraded it? Sure, there are a few less trees around Site Lambda, but there is also now a fully-functioning chicken cooker, which provides not only life-sustaining food but philosophical food for thought; there’s also been a return to activity on the server (as evidenced by the vocal reactions we get from other TAG members whenever they see how many of us are online at once); surely these are enhancements, no? Or is this just industrialist rationale for bringing over a herd of heavy-hoofed cows and letting them stomp all over a perfectly good field?

Bogost, Ian. Alien Phenomenology Or What It’s Like To Be A Thing. 2012.