A Digital Poetry Writer: Yaxkin Melchy and Lisa Gitelman

Web writing or moving our works on the internet means never relinquishing while there exists this universe of expressions that appear and disappear, that are created and erased. The web is a riddle to write.

(Melchy 2011, 35).

The subtitle of this chapter from Lisa Gitelman’s book Paper Knowledge attracted my attention since I skimmed through the semester readings–knowing by PDF. When you get most of your semester’s readings on a USB or a Dropbox file, as has mostly been my case since my M.A. years in Tijuana, you eventually get to understand how stupid it is to print 100 pages one week and totally dismiss them next week until the end of semester (at best). Plus, digging into the thousands of photocopies left behind to reread an interesting passage can become like finding a needle in a haystack. So you give up trying to materialize your readings and start reading them as you should’ve done in the first place–on your computer screen. Or e-reader, or tablet. Suit yourself. The thing is, if you really like reading, most of your material will eventually be in PDF format. Increasingly. I know many colleagues and friends still stand for the books’ materiality (such romantic, pseudo-bohemian aspects like “the smell of a good old book” or “the feeling of the pages in my fingers when I turn them”), but sometimes the only way to get access to some texts, in a world of urgency and saturation, is through digital formats, mostly HTML and PDF. We get access to important portions of knowledge through texts that do not have a material coalescence.

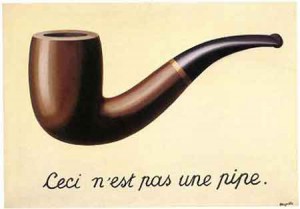

It is interesting that Gitelman starts her arguments by invoking the meta-representational dilemma posed by Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe, later studied by Michel Foucault, which uncovers the artistic process of mimesis as a representation that wishes to take the object’s place, but leaves an absence instead, a kind of ghostly presence which is probably related to Walter Benjamin’s concept of “aura”, that non-reproductible, almost divine feature of original paintings that mechanical copies would not attain. Benjamin would not have thought that aura would then move to previously non-aural artistic processes, such as traditional photography when digital photography came to replace it, or from obsolete music players and video game consoles. In the middle of the discussion about PDFs “page images” (as defined by Gitelman 2011, 115) resembling print pages while not entirely being such (becuase of the lack of materiality, its most important feature), the auratic argument is one of the main positions at stake.

Here’s where the task of writers who release (I find this verb mor accurate than “publish”) their works online gets into the stage. There are hubs of writers, like the Alt Lit movement in US (using this contested term to refer to blogs such as Pop Serial and New Wave Vomit) or the “Savage Poet Network” blog in Mexico, who in a way have given up their right to get an economic profit for their writing. Most of them have published their work under alternative licenses, such as Copyleft and Creative Commons. I know this is quite a deal for people in Quebec, for example, where the writer unions and associations have struggled for the aknolwedgment and rights to be paid for their creative work, but it also poses a different approach to the possibilities of network publishing.

I believe that poetry read on paper drags a History of literature and a body that is the material itself–the history of that paper. Poetry on screens is not better or worse, it has another form and other ways or entries for us to perceive the poetic, we’re talking about interactions like Internet allowing us to have access through a screen to contents that otherwise would be almost impossible to read due to its historical or geographic distance (Melchy 2011, 34).

Yaxkin is, as his Australian translator Alice Whitmore calls him, “a young self-published Mexican poet and founding member of the Red de los poetas salvajes [Savage Poets Network]” (Whitmore 2013, 42). In fact, Yaxkin is the brain and hand behind the Network. He invited several poets to publish their works online, then created projects such as anthologies and compilations, so that “the Red began as a small-scale blog and eventually transmogrifed into a vast, unoffcial online journal and forum” (Whitmore 2013, 43). He did this as an alternative to Santa Muerte Cartonera, a project he was holding at that time (2008) with the Chilean poet Héctor Hernández Montecinos, one of the first independent publishing houses to use cardboard as primer material for the creation of their covers (known as the Cartonera movement; for more information see Akademia cartonera, a primer of Latin American cartonera publishers published by U Wisconsin-Madison). Given the strong emphasis of materiality in the cartonera projects, instead of proposing a sort of “digital cartonera”, Yaxkin decided to apply both the digital and the material sides of publishing in the Red, since many books were published both in digital format and as chap books or in paperbound editions. Later on he would keep on mixing digital and printed media in his project 2.0.1.3. editorial.

The ambiguous nature of PDF (one would say its “simulacre”, following Baudrillard, rather than its “nature”) is akin to the amphibious strategy of Melchy’s project. When published in PDF viewing sites, such as Issuu, the experience of reading is even simulated by a page-flipping sound and flashing page corners to suggest movement. The PDF is like the sample in a virtual store, and the ideal paper sample keeps on being the one to have (at least when it’s not “grey literature”), even if the PDF version is stored in our computer and can be readily printed. We can see that the ungraspable, almost ghostly presence that Gitelman grants to PDFs is not fully realized in digital projects like this. Even though Melchy mentions the commonplace of multimediality as a possibility within the digital (“Poetry read on computers can be accompanied with video, audio, interactivity and even immediate feedback”, Melchy 2011, 35), there are no audiovisual contents in the Red’s PDFs, but in the blog itself instead. In this sense seems to be true that ” The portable document format thus represents a specifc “remedial” point of contact between old media and new” (Gitelman 2014, 115). The ground is there for the taking, but the users have only dealed with a limited number of possibilities, still dominated by the printed page format.

Within Yaxkin’s work there is a twist on the audience intended, though. The use of such simple apps as Nick Ciske’s Bynary to “read” binary code fragments included in Poesíavida will reveal us a multi-level reading process, in which not all the content is intended for human eyes. Some of Yaxkin’s work is only “readable” by machines, which doesn’t mean such machines will interpret such readings, just load them and (if asked for) display them. However, how far are we really from digital poetry?

There are things I don’t share with Gitelman’s approcach. For example, she says that in the PDF technology there is an orientation toward the author rather than the reader” (Gitelman 2014, 124). Even free PDF-reading programs, such as Foxit, have already integrated editing, commenting and fill-in tools, let alone the Canadian Government PDFs that generate a barcode when properly written on. So even in the rigid form of PDF, there are many ways to distort the text, as it was the case with printed pages, to add and erase things, to include commentaries. And in the end the file is never the same, even so when the program asks us to save the changes before closing the document. However, it is undeniable that PDF won over other text files because of its “natural” tendency to lock text editing while allowing (within certain limits) text copying. This is why web publishing sites like Issuu are so popular among comercial firms, but also among independent publishers. It gives an impression of materiality, with all those stacks, shelves and bookmarks. A virtual library potentially full either of grey literature or of avant garde experiments on readability in a post-print era. Hmmm.

References

Gitelman, Lisa. “Near print and beyond paper: knowing by *.PDF”. Paper Knowledge: Toward A Media History of Documents. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2014, 111-135.

Melchy, Yaxkin. Poesíavida. Tijuana: Kodama Cartonera, 2011.

Whitmore, Alice. “Four Poems by Yaxkin Melchy”. The AALITRA Review: A Journal of Literary Translation, Melbourne: Monash University, No.6, 2013, 42-55.