Interacting with Print – The Multigraph

Interacting with Print is an interdisciplinary, inter-institutional research group devoted to the study of European print culture in the period 1700-1900. IwP is nearly ten years old, and has members and collaborators from McGill, Concordia, the Université de Montréal, Stanford, the University of Toronto, Simon Fraser University, the University College of London, the University of Edinburgh, and the University of Virginia, from different departments such as English, History, German, and Modern Languages. This collaborative approach enables them to “build a solid understanding of the cultures of print in a way that disaggregated studies could not… Interactivity is both the group’s topic and method: in order to study the interactions of the past, IwP creates new kinds of interaction in the present” (interactingwithprint.org).

The group’s primary goal is to use interactivity as a lens through which they examine print culture and media history. They are interested in how people interacted with printed materials, how they interacted through these printed materials to communicate and interact with each other, and how “printed texts and images interacted within complex media ecologies.” Interactivity is the key to their investigation: “‘Interactive’ is a word most often associated with digital technologies, but we contend that a nuanced and historicized concept of interactivity is key to developing a deeper understanding of print, which emerged as the predominant communications technology in Europe in the period 1700-1900” (IwP).

The Multigraph

Jonathan Sachs approached me to work on the Multigraph, an innovative collaborative book project, in June. He explained that the project is a direct extension of the group’s goal to change current conceptions of print media. The plan was for the book to address “the variety of cultural practices of intermediality prevalent in Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,” and to “investigate how individuals interacted with printed matter, how they used print to interact with each other, and how print itself interacted with other influential media from the period, such as handwriting, illustration, sculpture, the theatre, musical performance, public readings, and polite conversation” (IwP). By examining this sort of interaction, the multigraph aims to provide readers with a “systematic overview of key concepts for the study of this vital period of media transition, from print’s emergence as the predominant communications technology in Europe until the onset of electronic media in the twentieth century” (IwP).

The Methodology

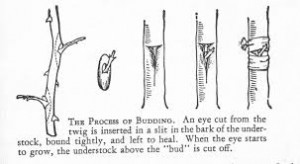

Among the contributors, this project is nearly always discussed using organic metaphors. While the structure of the multigraph may at first seem like the Exquisite Corpse game, the transparency of the process makes it much more like growing a garden. There are three phases – seeding, grafting, and pressing, and they correspond rather elegantly to spring, summer, and fall, or planting, tending, and harvest.

In the seeding stage, participants were asked to offer brief contributions on a key concept for the volume from any area of their own research. The seed had to be generative, so as to motivate further additions from other contributors: “The ideal seed is one that can grow in several directions. It encourages the contributors to think about the openness of research questions.” The digital seedbed contains nineteen seeds now, and it is quite different from the initial set of seeds; like any organic matter, any seeds that did not thrive in the growth phase simply died, or had to be pruned.

During the grafting stage, authors were expected to expand on at least two other authors’ seeds by about 500-1000 words per graft, but they could also contribute in any way to any of the available seeds. As in any good garden, the point of the graft was that it must take – it required consideration of the ideas of another and an attempt to draw connections with thoughts that are not one’s own. In order for a graft to survive, and to promote subsequent grafts, it had to integrate well.

The pressing stage is concerned with the fixation of the project into a stable form, to shift from the vitality of the web to the more permanent form of the hortus siccus, the specimen book of pressed flowers. Authors took on the role of editors, in this phase, and began to prune and refine the seeds into a finished product. Each author was responsible for editing his or her own seed, but any author could edit any part of the multigraph. One of the most interesting and indeed collaborative aspects of the project is that, in this phase, there was absolutely no hierarchy between the authors and the editors.

The multigraph is, at its core, an experiment in changing the way scholars think and write about print culture and the history of media. It is particularly interesting that the platform IwP is using to perform this experiment is a digital one. We use a private, password-protected Wiki, but it functions quite like the Wikipedia we are all familiar with. Anyone can create a page (the “seeds”), anyone can add anything to any page, and anyone can edit. There is no visible indication of the authorship, although administrators can access that information.

For a project that is so deeply concerned with print as a form, the choice to use this format for the writing is significant. It changes the nature of the text because it transforms the author(ial)ity of the writing. The goal of the multigraph is, at its core, to “draw on the interactions of both digital and print media, ultimately taking the form of a printed book, but one whose creation utilizes the collaborative tools of online communication” (IwP), however, that very collaboration causes some unexpected effects.

Collaboration is a fairly rare thing to see in academia. The reason for this is that collaboration and authorship exist on a plane of inverse proportions. The more collaborative a work is, the more nebulous the authorship becomes. This is a problem for scholars because their value is determined by how much they publish. The tired old “publish or perish” still rings true, and only gets harder to do as the world becomes increasingly digital. Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s book Planned Obsolescence addresses this issue:

“Academic institutions are facing a crisis in scholarly publishing at multiple levels: presses are stressed as never before, library budgets are squeezed, faculty are having difficulty publishing their work, and promotion and tenure committees are facing a range of new ways of working without a clear sense of how to understand and evaluate them.” (Fitzpatrick)

When we consider this project and the people who have produced it, it seems only logical that this sort of work would emerge as their final product. It is also easy to imagine how this format could be adapted and applied to any number of projects in any number of fields, and yield all kinds of fruitful discourse. However, with Fitzpatrick’s point in mind, we can see the difficulties it may encounter as it gains the momentum it will need to become more than an interesting and unique prototype. In this sense, the multigraph is an experiment that might never have been conducted, were it not for this group who has interactivity as both their topic and their method.

Ultimately, the goal is to publish this multigraph as a book. Publication is the teleology of all academic writing, and this book is no different – except that it is entirely different. Its form will be the same as most other books, but there’s a blurring in the content that emerges from its unusual authorship, which is part of the multigraph’s purpose: to reduce “author function,” as Foucault would see it, and to make this a print object that is uniquely concerned with print. This project is something of a unicorn, however, because unlike most academic writing, the group made the conscious choice to “move in a different direction than the academy’s increasing over-reliance on measures of accountability, in which, unable to measure what we value most, we have come to value what we can measure. Effacing the acute measurability of academic work is a first step in moving past the absurd — and in our view deleterious — tendency towards quantifying the assessment of learning and research today. It is time to develop new models of creativity and thought that are not easily subsumed within the accountant’s black arts. This project intends to affirm the argument that when it comes to the making of ideas the whole is always greater than the sum of the parts” (IwP).

Works Cited

Interactingwithprint.org

Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy. New York: New York University Press, 2011. Web.

Foucault, Michel. What Is An Author? Trans. Josué V. Harari. Movement Research. 22 February 1969. Web. 22 October 2014. http://www.movementresearch.org/classesworkshops/melt/Foucault_WhatIsAnAuthor.pdf

Aristotle. Poetics. Trans. S. H. Butcher. The Internet Classics Archive. Web Atomic and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 13 Sept. 2007. Web. 4 Nov. 2008. ‹http://classics.mit.edu/›.