Labanotation: The Topology of the Moving Body

“In its diagrammatic nature, topology is a persistent encounter with the shape of language. In moving from the haptic totality of the book to the visual totality of the diagram, topology allows us to reengage with the notion of the textual corpus–as a body in space whose surfaces and contours have meaning. In place of the book’s geometric continuity…topology marks an entry into a textual universe of far greater formal and structural diversity. In returning us to the question of form, topology is also a figurology” (Piper 390).

This quote by Andrew Piper in “Reading’s Refrain: From Bibliography to Topology,” made me think about the text as a three dimensional “body in space” and the varied shapes and “structural diversity” that this concept of the text can illuminate. Both Piper and Franco Moretti take up literature as their object from which to create a topology, but I began to wonder whether this type of diagrammatic approach would be possible with any other type of art. Of course, I always seem to return to dance and performance, and as soon as I began to think about actual bodies in space and the alternative ways they might be recorded or dissected, I remembered the geometrical notation of Laban Movement Analysis.

Rudolf Laban (1879-1958) was a Hungarian dance artist and theorist and a pioneer of modern dance in Europe. He developed Labanotation in 1928 as a means of archival notation and movement analysis, and it is used to this day, even in the development of robotics and human movement simulation. Labanotation uses abstract symbols to define:

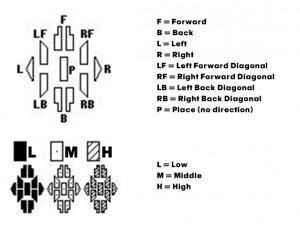

Direction and Level of Movement

The static shape is a rectangle, denoting no movement. It is adapted to demonstrate the eight directions: forward, back, side left, side right and the four diagonals. The shading within the shape signifies whether the level of the movement is low, middle or high.

Parts of the Moving Body

The shapes are arranged on a vertical staff to indicate which part of the body is moving. The center line of the staff represents the center line of the body. Symbols situated on the right represent the right side of the body and likewise for the left.

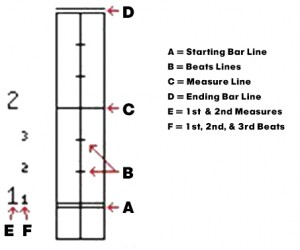

Duration of Movement

The staff is read from bottom to top and the measure is marked by bar lines. The length of the shape/symbol on the staff denotes the duration of the movement. Weight transfer, spatial distance, spatial relations, turns, particular body paths and floor plans are all notated by specific symbols. Jumps are indicated by an absence of symbol, which shows that no part of the body is supported or in contact with the floor.

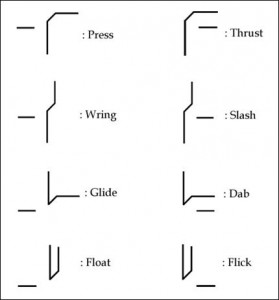

Dynamics of Movement

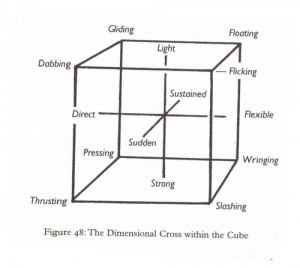

Effort symbols are used to indicate an increase or decrease in movement energy. The four categories of quality are:

Space: Direct / Indirect

Weight: Strong / Light

Time: Sudden / Sustained

Flow: Bound / Free

Labanotation not only provided a new way to record movement that would help keep traditional choreography alive and well, but also changed the way we think about dance. Laban successfully liberated dance from the formal constraints of music, narrative, steps and “technique,” focusing instead on the basic shapes and directions of a body in motion.

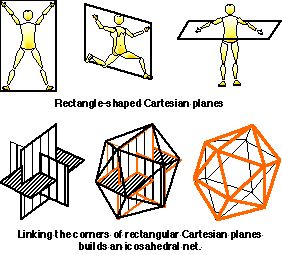

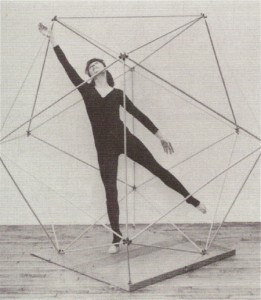

Laban saw that dance had evolved in a flat space, limited by the space of the theatre and other spaces of performance, and wished to restore depth to dance.

He used the icosahedron to indicate a volume of multiple directions, thus freeing dance from the flatness of the stage.

Laban also separated dance from its entanglement with music–movement for Lacan did not pander to an outside source of melody, rhythm or meter but rather could be sudden or sustained, direct or flexible, light or strong, depending on the impulse from within the dancer’s body. By freeing dance from music, Laban also freed it from time.

In relation to weight, Laban realized that body movements couldn’t be isolated from the flow of weight in the body and that “for every muscular contraction there was a relaxation,” yet by freezing the body at different points in its trajectory, using photography, 3D modeling, drawing or mapping, Laban was able to identify where the subtle shifting of weight began (as an impulse) and receded.

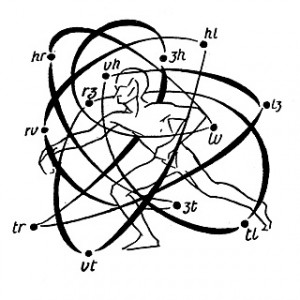

The “Kinesphere” is the Laban Movement Analysis term for the zone of possible movement of a human subject:

In “Laban’s Choreosophical Model: Movement Visualization Analysis and the Graphic Media Approach to Dance Studies,” Nicolas Salazar Sutil explores the influence Rudolf Laban has had on the way we understand human motion as a collection of fixed points in a movement continuum. Sutil writes “Whilst intuition knows the movement from within as a continuous whole traversing space, an analytical eye encourages us to think of movement and rationalise it as a series of immobile divisions. This breakdown of movement into units” effectively “seizes the continuous flux of movement” (148).

This topological approach is essential to the theoretical study of movement, because when “this meaningless flow becomes identifiable as a fixed object of analysis,” it also becomes “an object for documentation and reconstruction” (148). As Laban puts it, “we consider our snapshots separately only for the sake of analyzing the characteristics of the whole flux” (qtd. in Sutil 148).

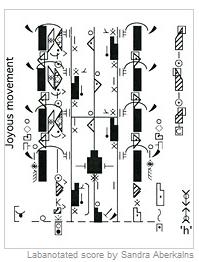

Andrew Piper’s conception of textual and literary topology encourages us to consider reading a “deeply visual experience” and to “think about language as a form of action rather than expression” or that “which can be mapped and seen” (387, 377). Likewise, methods of drawing and kinetographic inscription such as Labanotation highlight the activity of dance, rather than its expressionism. Laban’s topography serves the purpose of analytical examination and provides a record of movement that can extract from a random flux of motion a series of basic units within which to construct ordered sequences and patterns (Sutil 148).

Piper writes that “the topology itself is largely metaphorical….Unlike the pages of a book, which can never be observed all at the same time…the topology allows visual access to a textual corpus in its entirety. It replaces the haptic totality of the book with the visual totality of the diagram” (388).

Likewise, whereas individual body positions in dance can never be observed all at once since the body is in constant motion through space, Laban’s notation allows some sense of “visual access to a textual corpus in its entirety” by way of mapping corporeal tendencies in space that span across different bodies, places and temporalities (Piper 388). Laban’s achievement in the formal conceptualization the dancing body is not unlike Franco Moretti’s statement on what graphs and maps can reveal about literature: “Form is precisely the repeatable element of literature: what returns fundamentally unchanged over many cases and many years” (225). These types of approaches are thus shown to reveal, not only the architectural “scaffolding” that lies at the core of a work of literature or a piece of choreography or movement, but also we see how topology can be a useful tool for understanding history, legacy and heritage. Laban’s notation made it possible to record movement on the page, increasing accessibility to choreography and eliminating the human agent who would need to teach said choreography to the dancers of the future. But Laban also changed the way we think about the body in general.

By using the Platonic shape of the icosahedron to demonstrate the capabilities of human movement, Laban invented a somatic mathematization that is both organic and yet also void of the human. Sutil notes this hybridity: “What is remarkably contemporary about Laban’s writings is that they present this relationship between body and ideal space not in a strictly Pythagorean or Platonic sense, that is, not from the point of view of a metaphysical and totally bodiless agency. The Platonic solids are not mathematical objects, they are real-life models of harmonic movement” (161).

There are many similarities between Labanotation and the topological methods that Piper and Moretti offer. These types of methods change how we think about narrative expression, but they also offer a new way of thinking about the text or the object of dissection. Just as Christian Bök’s experiment with Jekyll and Hyde in Already Bad Enough When the Name Is But a Name offers us a new way to visualize the way these characters interact within the text (using a statistical analysis of Stevenson’s use of their names), so too might Labanotation offer a new way to read the narrative of Swan Lake, for example. The difference between the literary and the dance object in these experiments is that whereas literature is produced by a human, once it is on the page, it becomes its own object worthy of analysis. Dance, on the other hand, is inseparable from the human body. The dancer’s body is both canvas and paintbrush, and the production of dance art hinges upon movement as a tactile and experiential sense.

How can the dancer’s agency or subjectivity be accounted for in diagrammatic methods of distant reading such as Laban Movement Analysis? And how does something like Labanotation change the way we think about the body? Is dance even possible without a body, or without multiple limbs or range of motion? These are questions that have arisen and will continue to interest me throughout this exploration.

Works Cited

Moretti, Franco. “The Slaughterhouse of Literature.” MLQ: Modern Language Quarterly 6.1 (March 2000): 207-227.

Piper, Andrew. “Reading’s Refrain: From Bibliography to Topology.” English LIterary History 80 (2013): 373-399.

Sutil, Nicolas Salazar. “Laban’s Choreosophical Model: Movement Visualization Analysis and the Graphic Media Approach to Dance Studies.” Dance Research 30.2 (2013). 147-168.