Virtual Shtetl: Mapping as Postmemory

I first found out about Virtual Shtetl while sitting in the Warsaw Jewish Community boardroom overlooking the city’s central Pałac Kultury. I was going on Birthright—a free trip to Israel for young Jews of the diaspora—with a Polish group (the Canadian division of Birthright told me that I wasn’t Jewish enough to go, but that’s a story for some other space) and I asked how I could participate in Poland’s Jewish community from Montreal. The response I got was something like, “You could volunteer and translate the entries on Virtual Shtetl, for example, into English.”

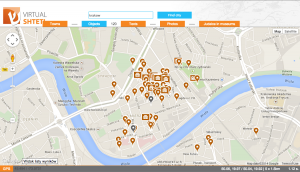

Virtual Shtetl (Wirtualny Sztetl) is a project that seeks to unearth Polish-Jewish history that was destroyed, lost, or forgotten during the Holocaust. The Virtual Shtetl website is divided into seven main archival parts—“Towns”, “Sites of Martyrdom”, “People”, “Glossary”, “Gallery”, “Map” and “Bibliography”—of which I will focus on the “Map” aspect, which is in my opinion the most interactive and intriguing.

Piece by piece, Virtual Shtetl reconstructs lost spaces of Jewish history by way of geographically locating Jewish places that either still exist the way that they did before the Holocaust, that no longer exist, or that exist but in a way that is no longer necessarily Jewish (for example the building that was the synagogue in Skawina still stands but now houses a convenience store) and archiving them onto their virtual map. The map is not necessarily “complete” but is well populated and most entries—particularly those for big cities—are translated. The project relies largely on donations and the work of volunteers and interns to populate the map.

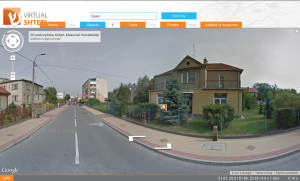

Currently, their website is a resource for scholars, tourists, and locals that allows them to discover bits of Polish-Jewish history interactively through Google Maps, where they can not only search a specific town, they can go into street view and virtually stand in front of a building that was formerly the town’s synagogue and presently looks like any other house on the street, for example the former synagogue in Grojec:

The project itself is extremely ambitious. As you’ll see if you visit their website or Facebook page, they seek not only to create a map-based database of Jewish places in Poland, but also to create exactly what the name of the project indicates: a virtual shtetl—a Jewish town or community—that is in dialogue with one another online. Their description of the project on their website is as follows:

The “Virtual Shtetl” is devoted to the Jewish history of Poland. Currently, our portal is a source of information, but in the future it will also include an interactive system by which Internet users will interact with each other. It will create a link between Polish-Jewish history and the contemporary multicultural world. (sztetl.org.pl)

The goal of this project is not only to discover lost fragments of Jewish life in Poland and to map them geographically, but also to reestablish the actual community ties and atmosphere that were lost with the extinction of Polish shtetleh through an interactive website. The concept of “creat[ing] a link between Polish-Jewish history and the contemporary multicultural world” complicates this notion further as the project interacts with many of its followers through their Facebook page which is called “Virtual Shtetl Portal”, described as a space “Dedicated to the documentation of Jewish life and heritage in Poland, the Virtual Shtetl Portal is not a place, but rather the community by which it is created” (Facebook, emphasis mine). Though the project does not physically appear in the streets of small towns and in the cemeteries of big cities—there is no plaque on the convenience store in Skawina telling its patrons that the building was a synagogue less than a century ago, and it is even possible that the people who run the store are unaware that it is marked as a synagogue on Virtual Shtetl’s website, let alone that the building they do daily business in was formerly a place of worship—the project is meant to inhabit the spirits and minds of the community members it gathers through collective reconstruction of memory through mapping.

In many ways, using Google Maps as a template makes the map of Poland appear less subjective to the viewer: the map itself appears not to have any biases. However, the icons used to mark points on the map of Poland are anything but generic: the synagogue icon depicts an old-style synagogue with a rounded roof implying a wooden structure (the type that you would have seen in pre-war shtetleh), the cemeteries are marked with icons depicting distinctly rounded Jewish tombstones, the places relevant to Jewish history or tragedy are marked with rounded dark icons that resemble regular Google Maps markers, though these have a white Star of David in the middle of them.

Virtual Shtetl has used Google Maps as a template and has customized aspects of its aesthetic, programming and imposing various aspects of Jewish history onto a widely accepted map of Poland. It is the user who chooses which layers of Jewishness to impose onto the map of Poland in the “Objects” tab of the map interface, selecting from different options grouped under the headings “Information about the town”, “Jewish community before 1989” (the year when communism fell), “Heritage Sites”, “Town today” and “Sources”. The options for marking this virtual map include labels such as “Cemeteries”, “Education and culture”, “Trade, industry, services,” “Synagogues, prayer houses and others”, and “Sites of Martyrdom”, allowing the user to choose what aspects of Jewish life they wish to uncover, remember, focus in on, or ignore.

These customized icons and layers change the way that the viewer reads the generic, widely-accepted map of Poland: it is no longer Google Maps as one might view it from the regular Google browser, it is Google Maps with layers of Jewishness transposed onto it. In fact, this virtual map of Jewish Poland figuratively, or perhaps virtually, colours outside the lines: Jewish sites that are no longer a part of Poland, sites that are now in Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus and Russia are also marked with synagogues, cemeteries, and the like, showing a discrepancy between what the project considers to be “Jewish Poland” and the generally accepted boundary of Poland. Virtual Shtetl reaches beyond the boundaries drawn by Google Maps.

As a literary scholar, I can use Virtual Shtetl as a research tool to see what is left of, for example, someone like I.L. Peretz’s hometown of Zamość. Using the various filters, I can search for synagogues, cemeteries, schools and other Jewish organizations and discover whether or not they still exist. I would not have to travel all the way to Poland to discover what parts of Peretz’s Zamość are left, I could simply swoop into street view to consider whether or not it might be worth travelling to in person.

As a genealogical researcher, I can look up the small town my grandmother grew up in and see whether or not there was a synagogue in the town before the war when she was a little girl to consider how religious my family may have been before the war. I can search for cemeteries in the area where forgotten relatives might be buried. If, for example, there wasn’t a synagogue or a cemetery listed for the town, I could zoom out and find the synagogues and cemeteries listed in neighbouring towns and figure out which would have been most convenient for my family to travel to. Instead of jumping in the car and dragging my aunt around the hilly Polish countryside for a day, I can now decipher whether or not a particular site is worth visiting, whether or not it is open to the public, and exactly what is known about it before I get there. Though aspects of visiting such a site in person are arguably just as important as finding the site and discovering its history—for example interactions with the locals, the bumpy car ride, the fresh cherries, the ice cream breaks and spending time with my aunt and hearing her stories—are missing when using Virtual Shtetl, the map function of the website is still an overwhelmingly practical tool, even with its limitations. It is a great place to start one’s research and a great place to share one’s discoveries even though not every Jewish place in Poland is accounted for and not every road in Poland is virtualized by Google Earth.

In J.B. Harley’s article “Deconstructing the Map”, he urges his readers to read maps not as aesthetic objects, but as “cultural text” (Harley 7). A map like Virtual Shtetl is nearly impossible to read as anything other than a rich cultural text which reveals the social implications of not only the Holocaust and practices of postmemory, but also the cultural complexity of creating such an object. In her article Museum as Memoryscape: The Virtual Shtetl of the Museum of the History of the Polish Jews, Pauline Sliwinski notes that, “According to the website’s Google analytics, from the site’s launching on June 16, 2009 until May 31, 2010, there were a total of 299,735 visitors to the site. 82 percent of users [were] from Poland; 6 percent from the United States; 2 percent from Germany; 2 percent from Israel and 2 percent from the United Kingdom” (Sliwinski). These statistics point to the fact that the website is predominantly used by Polish users, an important statistic as it challenges many stereotypes assumed about post-Holocaust Poland. In fact, the museum that backs this project is one of a handful of Jewish establishments supported by the Polish government: “The Polish government has made a programmatic effort to change the country’s image in the eyes of the Jewish world, through diplomacy and artistic and cultural collaborations” (Lehrer 202). Reconnecting Poland with its Jewish roots is on the national agenda, it is no longer a small grassroots movement. Sliwinski goes on to note that it is possible that the “virtual” aspect of Virtual Shtetl could influence how users feel about dealing with such rich and loaded historical material: “Through this medium the differences between Poles and Jews are given less importance than their similarities and common interest in preserving the memory of the vanished cultural and physical landscapes in which Jews were a significant part” (Sliwinski). The user, in other words, does not have to deal with the cultural implications of physically entering into a space that could be potentially confrontational or emotionally uprooting, but rather the user is allowed control of their experience in the privacy of their own home. In this virtual space, the user is free to be guided strictly by their own curiosity and personal interests, rather than being restricted by the way that a space is curated in a museum exhibition or by the boundaries that social conventions impose.

Effectively this project reveals that Poland itself is in a state of postmemory. Marianne Hirsch describes “postmemory” as “the relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before—to experiences they ‘remember’ only by means of the stories, images, and behaviors among which they grew up” (Hirsch 5). Virtual Shtetl is a collective memorial act created by the “generation[s that came] after” the Holocaust in Poland. “These events happened in the past, but their effects continue into the present” (Hirsch 5), writes Hirsch. A project like Virtual Shtetl is evidence of the continuing effects of the Holocaust in Poland in its custodial goals, including the documentation of Poland’s Jewish cemeteries and goals of mapping these sacred places out on Google Maps as well. Upon the unveiling of the Museum of the History of the Polish Jews’ core exhibit, Piotr Wislicki, the chairman of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland, recently stated that, “There is no history of Jews without Poland[, a]nd there is no history of Poland without Jews” (Lyman). The intertwined history of the Poles and the Jews was wiped away by the Holocaust, forcing both groups to forget one another for a period of time, and now, after the fall of communism, both groups are slowly beginning to rebuild the memories that were lost, forgotten, or destroyed. Bernhard Siegert, in his article “The map is the territory”, writes, “A main feature of the analysis of maps as cultural technologies is that it considers maps not as representations of space but as spaces of representation” (Siegert 13). Through the space of maps, a space for the representation of what was lost to Poland during the Holocaust is found in Vitrual Shtetl.

Works Cited:

Harley, Jacob. “Deconstructing the Map.” Cartographica 26.2, Summer 1989. Pgs 1-20. Print.

Hirsch, Marianne. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012. Print.

Lehrer, Erica. Jewish Poland Revisited: Heritage Tourism in Unquiet Places. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2013. Print.

Museum of the History of the Polish Jews. Virtual Shtetl. Web. October 26, 2014.

— “Virtual Shtetl Portal—Wirtualny Sztetl.” July 3, 2009. Facebook. October 26, 2014.

Siegert, Bernhard. “The map is the territory.” Radical Philosophy 169, September/October 2011. Pgs 13-16. Print.