Probe #2: Maps “What exactly do they do?”

I spent a year and a half playing Legend of Zelda: A Link To The Past.

My brother and I got a Super Nintendo for Christmas from a rich aunt and uncle in 1993 and spent somewhere between the next 18 and 20 months doing almost nothing else in our spare time but play the game. We kept a notebook where we would update each other on things that we found when our kid-schedules didn’t line up, so if we placed without each other we would know what happened, but mostly we played together, passing the controller back and forth as our different skill sets were needed (Michael was much better at boss fights, where I excelled at hidden passages).

And we drew maps. We didn’t buy and official game guide and it would be years before we had an Internet connection at home, so we made the maps ourselves. Blocky and uncertain at first, the maps would spiral out, growing rhisomatically as we explored, until we found the edges of the small, digital world.

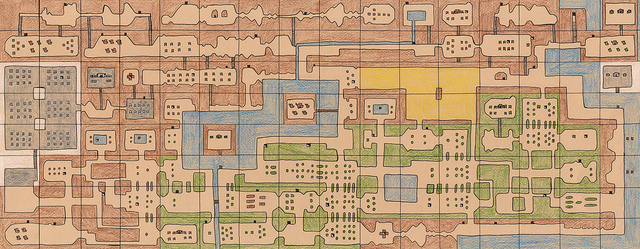

Hand-drawn Zelda map by Daniel Brown. You can see more of his work here: https://www.flickr.com/photos/51653338@N06/4751755703/

As we made discoveries, we annotated our maps. The landscape that emerged was built up not just of the terrain we encountered, but of our experience of it, a phenomenon similar to what Franco Moretti describes: “out of the free movements of Our Village’s narrator, spread evenly all around like the petals of a daisy, a circular pattern crystallizes—as it does, we shall see, in all village stories, of which it constitutes the fundamental chronotope. But in order to see this pattern, we must first extract it from the narrative flow, and one way to do so is with a map. Not, of course, that the map is already an explanation; but at least it shows us that there is something that needs to be explained. One step at a time” (Moretti 84). The maps we made were bound and dictated by the way that we experienced the game,

The maps each of us made were were profoundly influenced by our different play styles; as the game was different for each of us, our maps had “a different geography according to who was looking at it” (Moretti 81). My maps were littered with markings about item locations, suspicious cracks in rock walls that could be bombed to reveal caverns, shrubs that could be pulled up to reveal holes, treasure chests on ledges I had yet to puzzle out how to reach. My brother drew battle lines, noted where enemies were most densely concentrated, plotted out the safest paths through traps and treacherous terrain.

Without an official map placed over the game experience we had, the maps we made were produced by the way we explored. Official game maps are much cleaner and tidier, coolly rebuffing the impulse to annotate, standardized and sanitary. Official maps represent of the game experience the game makers want us to have, with connects to Jacob’s Harley’s assertion that “maps are authoritarian images. Without our being aware of it maps can reinforce and legitimate the status quo” (Harley 14). I still find official maps too confining, to neat; I still game with a notebook next to me, full of notes and doodles — and sketches of maps.

* * *

“Things are not always so neat. But when they are, it’s interesting” (Moretti, 85).

Charting the experience of gaming through making my own maps gradually led me to writing games. As in most areas of my life despite the fact that I had no idea what I was doing at all I decided to leap in and try it via an intense 6-week workshop called Junicorn, run by Dames Making Games, a feminist gaming organization in Toronto. It was during this process, banging my head against RPG Maker and over graphic-intense game creation engines, that I stumbled on Twine.

Unlike the other engines that I had were exposed to, Twine is text-based. It’s a simple interface for interactive storytelling, game making, and choose-your-own-adventuring. It’s simple enough to puzzle out, but Anna Anthropy has an excellent beginner’s tutorial so that you can start building a narrative immediately.

Using Twine, instead of writing linearly, the narrative grows rhisomatically. As you explore the implication of every choice and the resulting options, the narrative grows and splits off. With every fracture the narrative landscape take up more ground, feeling every outward for the edges of the story. There are a lot of ways to write multifoliate texts – Scrivener is a tool that was mentioned in class before, and I have even known people laboriously write games with branching narratives on hundreds of Powerpoint slides. The nature of Twine, and what sets it apart, is that the software allows you to lay out your story visually, to see the shape of the narratives as they branch.

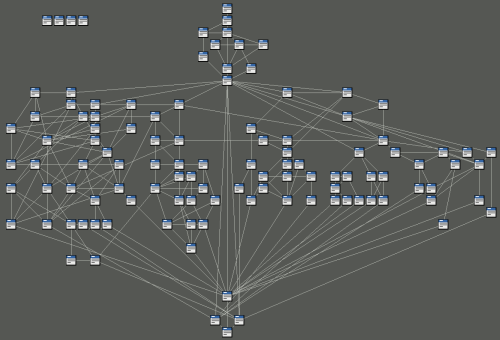

Eerily like maps

From OneGameAMonth Project: ” 109 content passages, with 238 links connecting them, containing over 8,000 words.” http://www.maximumverbosity.net/1GAM/2013/03/

Moretti talks about the way maps reveal “the direct, almost tangible relationship between social conflict and literary form. Reveals form as a diagram of forces; or perhaps, even, as nothing but force” (Moretti 103). t]The structure of the game maps and the structures of the guts of Twine games — interior and exterior views of the same narrative — echo each other, revealing this conflict or tension. This also gestures towards what Bernhard Siegert says when he talks about the Aristotelian concept of hylomorphism, the relationship between matter and form as manifested within maps: “the map is the territory. In this case this means that as the materiality of the map interferes with its contents, and as the medium of representation interferes with the representation of the territory (for which representation is an ontological condition), the map as a representation is deterritorialized by the map as a medium” (Siegert 16). I was sruck by how much the form and content of game maps and Twine games echoed each other.

The connection is made even more directly in the case of the tool Inklewriter, which has the compositional option “map mode” to help you visualize your piece as you write it. In her critique of the tool, Emily Short notes the illuminating limitation “the map gets increasingly tangled and tricky to read after a moderate amount of work, and as the lines cross it’s not always clear which of the connections represent choices and which direct choice-less progress from one paragraph to the next” (Short 2012). What I find most interesting about this observation is, again, the parallels betweent the narrative map and the geographic one: as a story can get tangled — too complex, overwritten, etc. — so can narrative maps. In the process, the medium itself becomes a constraint, a limitation that defines the sorts of stories that are being told, how many choices are available, how many branches reveal themselves.

I believe this is what Harley is talking about when he discusses “the narrative qualities of cartographic representation” as well as the “rejection of neutrality” in that neither can be disentangled from each other: cartography is narrative and narrative is cartographic, when it comes to game writing (Harley 8). The process of writing in Twine is extremely revealing about these cartographic biases, and it essentially works them out backwards: as cultural context seeps into and defines every aspect of map making, so the act of writing within a map limits the cultural production that comes out of it.

So what kind of games are produced within those limitations? Games like reProgram, an interactive exploration of meditation and BDSM, by Soha Kareem, wherein the circular, repetitive nature of meditative practice is juxtaposed with moments of violence. Some choices lead you farther away from the safety of the centre as they fracture outwards, increasing the players sense of risk and vulnerability; or, conversely, lead them back to a place of calmness and safety. Each of the player’s selections, each click, become choices toward violence to tenderness, each choice transmuted into action and changing the narrative landscape.

In games like Even Cowgirls Bleed by Christine Love, the act of selection is even more intensified: every decision is a gunshot (or, occasionally, the option is presented to holster your weapon). You must shoot to progress, revealing more text through acts of destruction, and as you pepper the game landscape with bullets it changes: tensions rise, relationships begin to erode. Every action, every choice, each necessary to propel the relationship forward, changes the terrain, making it more hostile, discovery as an act of violence.

I wonder if games, and specifically game scripts and maps, represent a space between the text and the map as Moretti imagines, a liminal space. When he talks about distant reading at the end of the chapter, Moretti states that “distance is however not an obstacle, but a specific form of knowledge: fewer elements, hence a sharper sense of their overall interconnection. Shapes, relations, structures. Patterns” (Moretti 94). As maps take stories and distill them, simplify them, reveal the shapes, in engines like Twine we see the shape of the narrative, the edges of the fictional universe, the patterns. Plus, both are meant for exploring.

Works Cited

Harley, Jacob. “Deconstructing the Map.” Cartographica 26.2 (Summer 1989): 1-20.

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History — 2.” New Left Review 26 (Mar-Apr 2004): 79-103.

Short, Emily. “Choice-based Narrative Tools: inklewriter.” Emily Short’s Interactive Storytelling. September 11, 2012. Web. October 26, 2014.

Siegert, Bernhard. “The Map Is The Territory.” Radical Philosophy 169 (September-October 2011): 13-16.

Works Discussed

Christine Love. Even Cowgirls Bleed. Love Conquers All Games. 2013.

Soha Kareem. ReProgram. 2013.