The Kanye West Phonotext: sampling, sharing, re-appropriation and racism

As a “graduate candidate” in literary studies, I often ask myself whether my analyses of unpopular, neglected poems, novels and plays are culturally relevant. This short essay considers some things that are perhaps too often ignored by English scholars — the immense relevance of American popular music, how music relates to current trends in culture and consumerism, and the manner in which most ideological and aesthetic exchanges occur in the phonotextual virtuality of the internet. In an interview on “Sway in the Morning,” Kanye West claimed that nobody can achieve more cultural relevancy than a “rap rockstar.” And it might be that Kanye is not completely wrong; he may even be right! Jason Birchmeier, a contributer at allmusic.com describes West as: “Far and away the most adventurous (and successful) mainstream rapper of the new millennium, changing his sound and style with each new album.” But when I think about Kanye, I don’t think “musician.” As can be attested to by those of you (suckers) that went to see him live at the Bell Centre last February, West thinks of himself as much as a clothing designer, a poet, and a visionary as he does a rapper or music producer. Part of this “rap/rockstar’s” success, according to Sway, is demonstrated in West’s capacity to “manipulate the internet,” to draw attention to the Kanye brand through the avenues of fashion, through YouTube, through paparazzi scandals, and so on. All of this demonstrates that in the world of hip-hop, cultural “relevance” does not merely rest in selling albums, nor does it rely on getting people to listen to mp3s; more important (at least to Kanye West) is in connecting looking with listening, in drawing phonotextual links between these virtual conglomerations.

In Jonathan Sterne’s terms, the internet has introduced “new praxeologies of listening,” permitting music to be more than a container of containers (as Sterne describes the mp3), but a platform of outward links. Sterne describes how the mp3 marks a change in the economy of musical exchange, introducing a situation where “data could be moved with ease and grace across different kinds of systems and over great distances frequently and with little effort” (829). But this “possibility for quick and easy transfers, anonymous relations between provider and receiver, cross-platform compatibility, stockpiling and easy storage” (829) is old news in the world of hip-hop. For decades, hip-hop has relied upon an interactive collective phonotext exceeding sound. As Jeff Chang shows us in his insightful “History of the Hip-Hop Generation,” the musical innovations of spread like fire in the late-70s: “cassette tapes passed hand-to-hand in the Black and Latino neighbourhoods of Brooklyn, the Lower East Side, Queens, and Long Island’s Black Belt” (127-28). Hip-hop has always been a “hyperlink” musical genre. When it comes to rhymes, breaks and beats, the logic of rap eludes most of the rules of “intellectual property” that constrain scholars in academic institutions. Borrowing, sampling, sharing and stealing are in fact crucial parts of the collaborative “phonotexts” that hip-hop inevitably opens up. According to Greg Tate, the hip-hop generation is always “about ten years ahead of culture in terms of embracing [and utilizing] technology” (43). We see how hip-hop takes the music sample to embody “an item that ‘works for’ and is ‘worked on’ by a host of people, ideologies, technologies and other social and material elements” (Sterne, 826). Drawn out of the noise of the internet and ripped from previous songs, the sonic trafficking done by DJs does not produce original scores so much as generating remixes and re-appropriations of previously recorded media. Social and material relations are always at the centre of the music. And as we see with the example of Kanye West, the lyrical emphasis on consumerism, race, and oppression are inextricable from the formal operations of technology, advertising, distribution, performance, and so on.

“Annotate the World” : Welcome to Genius

Sterne uses the mp3 as a “tour guide” through social, physical, psychological and ideological phenomena of which otherwise we might not have been fully aware; this essay uses Rap Genius as a means to discuss the same phenomena. “Annotate the world” is the Genius mantra. Search the relational database and you will discover a “world of communities,” each fixated on their own phonotextual genres (channels range from R&B genius, rock.genius; country.genius; news.genius; lit.genius; history.genius; law.genius; sports.genius; to many others). The site displays shifting narratives which vacillate between the critiques, rants and appraisals of participants. Everyone is eligible for an account, which allows for maximum participation in the collaborative annotation of the lyrics, aesthetics, production, and intertextual reference that occurs within and surrounding the thousands of featured songs. Rap Genius shows us how the internet can be used to organize, expand and store data about hip-hop, its history and relates all of this to current events. We also see how the interactive, visual, imaginative extensions of music take us outside the “contained” space of the mp3, beyond what Sterne describes as the “fine distinctions of the human ear” (834). Rap Genius, like the mp3, has altered the nature of the music recording industry as well as the actual and idealized practices of listening. Rap Genius is an internet hypertext mapping and storing the contours of hip-hop; it is an exegetic phonotextual knowledge base that is both structured and always open to alteration.

LOOP ONE : “New Slaves”

Sterne discusses mp3s as “cultural artifacts in their own right,” as a “psychoacoustic technology that literally plays its listeners” (825). As a means of testing the “Genius,” I began browsing the web pages associated with a couple of tracks from Kanye West’s newest album entitled Yeezus. How do fans and critics play with Yeezus? How does the mp3 “container,” in tandem with web-based music discussion boards open a situation where listeners, consumerism, culture and music play off each other? After all, “music” describes more than listening, viewing, sharing, trading, and stealing audio files, but represents a cultural dialogue — and in my view, this intercommunication needs emphasis. Thus how do the perplexing, ambiguous and infuriating messages of Yeezus escape simple hermeneutic interpretation, and demand an expanded virtual phonotextual analysis? Yes, Kanye sometimes raps like a misogynistic egomaniacal, elitist asshole, but this does not mean that his product is not of immeasurable capitalist and cultural value. If we are going to talk about “big data,” mass media, capitalist production via the phonotext, why not turn to the “rap rockstar” that ostentatiously proclaims “I am a god”? In the spirit of “distant reading,” as I browsed the site theory synchronized with scores of other cultural objects, feelings and images. Images of West’s clothing line led into vertiginous accounts of the American white establishment; ethics, bling, racism, politics, hate, hope, America. To view albums as single “containers,” as “cultural artifacts” is to ignore larger debates of what the world of music is doing. Rap Genius invites a formal analysis of music that acts, and thus aids in uncovering how a world of listeners are making sense of the larger controversies embedded within Kanye’s phonotext.

check out the link; you might even participate in the forum!

Here is a supplementary explanation about why Kanye thinks “we are all slaves”:

LOOP 2: “Blood on the Leaves” [Annotation from Rap Genius]

Sterne claims that the iPod introduced new ways of listening to music; and although mp3s are assembled by a variety of technologies, Sterne cites Philip Sherburne, that computer manipulation demonstrates “the ongoing dematerialization of music” (831). But when we listening to music through the channel of Rap Genius, what sorts of rematerializations occur? Take, for instance, “Blood on the Leaves” — where Kanye’s narcissistic lamentation about a break-up rematerializes the entire track of Nina Simone’s “Strange Fruit” — a mournful song about the lynching of countless African Americans. Jody Rosen criticizes the rapper is “well aware of how audacious it is to interpolate that sacred song into a monstrously self-pitying … melodrama about what a drag it is when your side-piece won’t abort your love child.” Meanwhile, the responses on Rap Genius include several extra-textual references that might help to make sense of the broader context of the song. One of the links posted is this video:

Rap Genius extends Jonathan Sterne’s evaluation of the “peculiar status of the mp3 as a valued cultural object which can circulate outside the channels of the value economy … enabling conditions for the intellectual property debates that surround it” (831). Kanye’s sampling of “Strange Fruit” ignites more than a conflict about intellectual property, but draws our attention to the reappropriation of a historical and cultural artifact, in this case one that explicitly speaks about the slavery and murder of countless African Americans. Although the original message of “Strange Fruit” is obscured by Kanye’s self-involved contemplations and the tight production of an aesthetically-pleasing song, Rap Genius displays how the phonotext cannot evade these illuminating and necessary debates.

LOOP 3:”Black Skinhead” (I recommend that you read the full Annotation for this one)

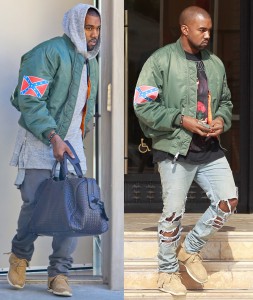

These are certainly not the first exemplifications of Kanye West’s words producing arguments about racism. But with Yeezus, merchandise may have generated as much public discussion about race than did the lyrics of his songs:

Through the “Genius lens,” merch becomes another component in the phonotextual narrative; although these images conflate and confuse matters, they also draw us back to the music. The jam’s provocative title is well-summarized by the Rap Genius community. (I found the link to the wikipedia entry on skinhead to be a very informative annotation for this track). As we have already developed, the re-appropriation (resyncing, remixing, re-defining) of symbols, iconography and lyrics (from the sacred to the profane) is one of Kanye’s greatest skills. These are, after all, perhaps the crucial components of any relevant phonotext — at least in the virtual world of pop. But can we take srsly this self-proclaimed “god,” this modern-day “Yeezus”? But when I turn to the news.genius channel, Zach Schwartz has this to say: Applaud Kanye West for Wearing the Confederate Flag

To conclude, Rap Genius offers more than some interesting table talk about sharing, sampling, re-appropriation, and racism. Kanye certainly “ain’t got the answers!” But at least phonotextual platforms such as these are getting us all to dig.

Works Cited

Chang, Jeff. Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. Reading: Ebury Press, 2007. Print.

Cross, Brian; Mark Anthony Neal; Vijay Prashad; and Greg Tate. “Got Next: A Roundtable on Identity and Aesthetics after Multiculturalism.” Total Chaos: The Art and Aesthetics of Hip-Hop. Ed. Jeff Chang. 33-51. New York: Basic Books, 2006. Print.

“Kanye West – Black Skinhead.” Rap Genius. Genius Media Group Inc., 2014. Web. 5 Nov. 2014.

“Kanye West – Blood on the Leaves.” Rap Genius. Genius Media Group Inc., 2014. Web. 5 Nov. 2014.

“Kanye West – New Slaves.” Rap Genius. Genius Media Group Inc., 2014. Web. 5 Nov. 2014.

Manhatten, Chris. “Kanye West Flips Out On Sway In The Morning Interview Nov 26th, 2013.” YouTube. YouTube, 27 Nov. 2013. Web. 1 Nov. 2014.

Maya, H. “Nina Simone – Strange Fruit.” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 29 Mar. 2011. Web. 7 Nov. 2014.

Rosen, Jody. “Rosen on Kanye West’s Yeezus: The Least Sexy Album of 2013.” Vulture. New York Media LLC., 18 June 2013. Web 20 Oct. 2014.

Schwartz, Zach. “Applaud Kanye West For Wearing the Confederate Flag.” News Genius. Genius Media Group Inc., 7 Nov. 2013. Web. 5 Nov. 2014.

Sterne, Jonathan. “The mp3 as cultural artifact.” New Media and Society 8.5 (2006): 825-842. Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

West, Kanye. Black Skinhead. Grooveshark, 2013. Stream.

—. Blood on the Leaves. Grooveshard, 2013. Stream.

—. New Slaves. Grooveshark, 2013. Stream.