Deforming the Human Interface: Glitches, Orlan, and Interacting with Biodigital Mess

The quest for “universals of communication” ought to make us shudder

– Gilles Deleuze (qtd in Galloway and Thacker, 23)

What universally communicative method could provide a better survey of the “manifest image” of the human face than Facebook? A search through the expansive territories of “face” gleans a uniform notion of expression embodying the same flat network of photo albums and timelines: “this is my face,” “I am this face,” “my face was here…” But what are we becoming through interface? And who isn’t becoming like everyone else?

The face is typically regarded as the body’s centre of sense and expression. Biological definition contains this singular organism within the epidermis, its movements correlated with the operations of the brain and central nervous system. Meanwhile, documented in social media databases, the self-involved posts always link back to pics of a publicly verifiable face. “Human subjects thrive on network interaction (kin groups, clans, the social),” write Alexander R. Galloway and Eugene Thacker, and the trafficking of face that occurs on the internet does not convince us otherwise. “[Y]et the moments when the network takes over — in the mob or the swarm, in contagion or infection — are the moments that are most disorienting, the most threatening to the integrity of the human ego” (5).

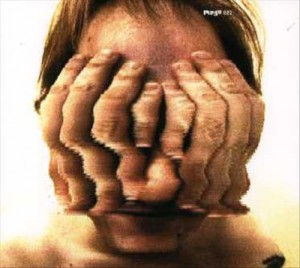

I receive a telephone call from a friend back in Saskatchewan… “Bad news,” they say. A neighbour’s face has been burned in a farming accident. Imagining the scarred flesh leads into networks and affiliations of other facial responses, their reactions to this news. It is perhaps most disturbing to consider a glitch in a familiar face; the face that becomes disfigured, the face that might be contagious infectious… Images of glitched faces provoke a unique array of “fellow-feelings” — ranging from compassion to disgust. These considerations need not be limited to horror films, but are both a biological and digital reality. This paper will consider something like this as its object:

Mathias Gmachl: GCTT CATT 2001

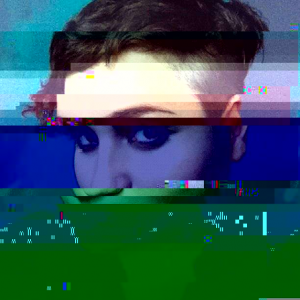

Of course, virtual and organic networks alike are always prone to these types of glitches. No matter how “flat” reality can appear when you have time to prepare for a selfie, a quick survey of the faces aboard the métro reveals varieties of countenances, all of which flourish with unique blend of gaps, dents, bruises, make-up and fissures. Whether it is through avoiding to meet their eyes in the street or if we follow them on twitter, we are in constant negotiation with “otherness.” But these interactions are not limited to “friends,” “colleagues,” and other Instagram users, but with the fields of outside “corruptive” entities, viruses and bugs that are enmeshed in our thriving social communities. And although many of these actants are invisible and undetectable, the right kind of glitch can threaten the unity, efficiency and function of assemblages. Galloway and Thacker aver that “this dissonance is most evident in network accidents or networks that appear to spiral out of control — Internet worms and disease epidemics, for instance” (5). But these exemplifications do not show a network that is in disrepair, but show one that “works too well” (6). For their function as well as their counter-functional disruptiveness, for their dangerous unpredictability and their interface-altering potentiality, glitches demand closer scrutiny. Perhaps Marina Galperina is correct to claim that “Glitch is the new selfie.” Here, for instance, are two more examples created via the app “glitché”:

Georg Fischer : Glitch Experiment

Dmitriy Krovtevich : Pixel Drifter

Galloway and Thacker ask how we might engage as both individual and social bodies, as parts of living networks involving “aggregates of singularities — both human and nonhuman — that are implicated in the network” all of which is “constantly undergoing changes” (70,71). Perhaps art provides response to these queries. In the “Glitch Studies Manifesto,” for instance, Rosa Menkman emphasizes the aesthetic beauty of such experimentations: “the glitch is a wonderful interruption that shifts an object away from its ordinary form and discourse, towards the ruins of destroyed meaning” (340). Performance art has a long history of exploring the glitchiness of the human form, using the body as an intimate interaction between technology, synthetic and organic material:

Exogene (1997)

from Precolombian Self-Hybridizations (1998)

African Self-Hybridization (2003)

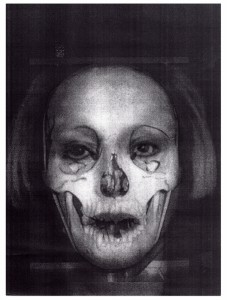

Though Orlan has never professed to be a “glitch artist,” her facial metamorphoses embody some of Menkman’s principles of “glitch art”: as a “shifting, ungraspable, unrealized utopia connected to randomness and idyllic disintegrations” (341). Quoting from Orlan’s official website, the artworks are described as

self-portraiture in the classical sense, but realised through the possibility of technology. It swings between defiguration and refiguration. Its inscription in the flesh is a function of our age. The body has become a ‘modified ready-made’, no longer seen as the ideal it once represented; the body is not anymore this ideal ready-made it was satisfaying to sign.

With a mantra that embraces pain, transformation and suffering, Orlan’s performances require surgical, manipulative, deformative alterations of her face for each public appearance. Media innovations are utilized not as progressions toward facial perfection, but as noisy disturbances of typical body language, as defacements of the smoothed and structured systems that try to hold face.

from Omnipresence Surgery (1993)

from Omnipresence Surgery (1993)

Through all the multiplications, subfunctions, microfunctions of the interface between organic and electronic materials, the internet offers fertile ground for viewing such facial metamorphoses. Orlan’s facial repertoire hightlights the gaps and fissures that thrive within the human network; her face becomes through symbiogenesis — process of composition whereby new organisms are formed out of two or more separate structures. The face is characterized by the messiness from whence it emerges, from what John Law describes as “a reality out there and beyond ourselves” (5). Orlan is always beyond the self, cannot be fixed. Her face is a lack of identity, “that which is elsewhere. Absent” (7). To remix of Samuels and McGann’s philosophy of deformative poeisis, Orlan undergoes a constant change whereby the face (and not text) becomes a site of process. These acts deform the possibility of anticipating particularities, “short circuit[ing] the sign of [facial] transparency and reinstalls the [face]” (30). Orlan’s collaborations with surgeons and surgical instruments display how poeisis can assume new “physiques,” and are far more impressive than a backwards reading of Wallace Stevens. As facial constancy is glitched, we are forced to look in the eyes of the unfinished character of construction and infrastructure. Glitches thus complicate simplified concepts of the face, diverting methods toward interfacing with multiple forms of presence.

Operation Réussi (1991)

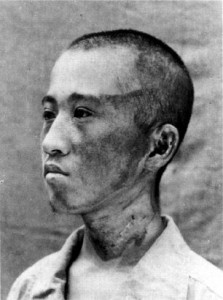

Orlan acts out the extremes of subjugating one’s physiognomy to the alterations, additions, divergences of the interface between medicine and art. We are caused to ponder what happens when the face “yields to such a remapping” until something “emerges as an imagination of something we do not know” (Samuels and McGann 38). The universals of communication are rewired through the symbiogenesis of artistic creation. But we are all subject to such constitutional glitches; indeed, the history of human faces is full of glitches. Lynn Margulis points out that human organisms are the result of “a long line of progenitors that can be traced back to the first bacteria” and these microbes continue to characterize who we are (qtd in Manning 91). “If it doesn’t kill you, glitch might help make you stronger!” But then, Walt Bogdanich’s essay on “The Radiation Boom” demonstrates that while new technology allows doctors to more accurately attack tumors and reduce certain mistakes, its complexity has created new avenues for error — through software flaws, faulty programming, poor safety procedures,” and a variety of other complications (166). Bogdanich reports 133 occasions where modulated radiation technology equipment was misused, occasionally glitches in the machinary accidentally administered fatal overdoses to hospital patients (168).

How are biotechnologies, electromagnetic waves, and digital uploadings altering notions of the human face? Does new media mean new faces? Eugene Thacker’s Biomedia “facilitates and establishes conditionalities, enables operativities,” to seek further to answer the question “what can a body do?” But we are also learning (sometimes via catastrophe) the limitations of biological and digital systemic operations. Both domains “inhere each other,” writes Thacker: the biological ‘informs’ the digital, just as the digital ‘corporealizes’ the biological” (7).Following John Law, however, we might regard “otherly mess” that is not easily incorporated into political, social, and philosophical analyses. Law elucidates the problems that result in the systemic othering of this so-called “mess,” those who are not easily incorporated into idyllic or smooth conceptions of human societies. Besides looking at glitchy art, how should we proceed through involving organic, synthetic and digital networks in order to address the symbiogenetic antagonisms of glitch? There can be serious ethical implications in disavowing the messiness that results in the fall-out of glitches. Perhaps these faces (which can be viewed at hiroshima-remembered.com) provide some clues as to why it is crucial that we try to “make sense of the mess.”

Out-there is certainly more of a mess than we can put a face to, and we certainly need to envisage (much) better methods of drawing attention to the gaps, abnormalities and exceptions that warrant critical attention. As our bodies interface with the rest, we inevitably share many of the same microbes, germs, DNA, and other detritus that flows in, out and through. A glitched notion of the human face demands new conceptions of realities which are neither coherent nor fixed, but highlights that we are part of the shifting collaborations and antagonisms that occur via biodigital interactivity. And as Law points out, we must become more cognizant of the “out-hereness as well as in-hereness” of such a reality. Network analysis thus necessitates also reckoning with the worms, bugs, and viruses that threaten the structure’s stability. Out-there/in-here glitch is not only poeisis — the creative randomness emerging out an error in digital circuitry — but a destructive and revisionary critique of infrastructures. Glitches certainly demand a broad reconsideration of face (of interface, of facing up), and may even move toward novel, more radical decisions to look courageously at the multiplicities and diversities that are thriving “out-there” as well as “in-here.”

Works Cited

Bogdanich, Walt. “The Radiation Boom.” Glitch: The Hidden Impact of Faulty Software. Ed. Jeff Popows. Montreal: Prentice Hall, 2011. 165-185. Print.

Fischer, Georg. “Glitch Experiment.” Fast Company. Mansuento Ventures, 19 Sept. 2014. Web. 19 Nov. 2014.

Galloway, Alexander R. and Eugene Thacker. The Exploit: A Theory of Networks. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007. Print.

Galperina, Marina. “Glitch is the New Selfie.” Fast Company. Mansuento Ventures, 19 Sept. 2014. Web. 19 Nov. 2014.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered. AJ Software and Multimedia, 2013. Web. 19 November 2014.

Krovtevich, Dmitriy. “Pixel Drifter.” Fast Company. Mansuento Ventures, 19 Sept. 2014. Web. 19 Nov. 2014.

Law, John. “Making a Mess with Method.” After Method. 3 (2003): 1-12. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Manning, Erin. Politics of Touch: Sense, Movement, Sovereignty. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007. Print.

Menkman, Rosa. “Glitch Studies Manifesto.” Vortex II (2008):336-347. Web. 10 Oct. 2014.

Orlan Official Website. NetAgence, 2014. Web. 16 Nov. 2014.

Samuels, Lisa and Jerome McGann. “Deformance and Interpretation.” New Literary History. 30.1 (1999): 25-56. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

Thacker, Eugene. Biomedia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004. Print.