Player-Generated Content and Transmedia Story Telling in Pokémon

Project Info

In these next few weeks, I will be writing about my experience on different Minecraft servers as a method to keep track of my thoughts on video games, not as a separate entity from literature and films, but as a part of a constantly developing transmedia culture that encompasses the different manners in which we create narrative.

To begin, I will be observing different player-made servers to explore how and why players create their own narratives through online resources such as Fanfiction, fan-art, fan comics and more importantly for my research, in Minecraft. I am interested in the implicit rules players create and follow to explore and emulate these narratives.

In this first week post, I will explore the Pokémon franchise. I will begin with my own personal experience on the different servers and my thoughts on the overall construct. Then, I will ground my research through a reflection on the relationship I found therein with different academic sources.

Player-Generated Content and Transmedia Story Telling in Pokémon

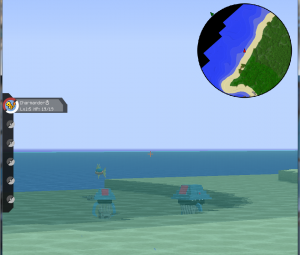

After spending the day playing on different Pokémon themed Minecraft servers, I can safely assume that as of yet, there is no online server that encompasses the entirety, nor the soul of the Pokémon Franchise. The attempt is noble, interesting and viable but demands experienced programmers. So far, what makes these servers “Pokémon” are the use of player generated content such as high quality models of different Pokémon, a battle system interface, the overhaul of the main user interface, and familiar environments such as the Pokémon Center and battle arenas. However, while the environments may lead to a feeling of immersion, the game mechanics feel skewed and take away from the overall experience of what one would expect from a first person adaption of a Pokémon game.

Visually, the environment lead the player towards a new and different experience of the Pokémon franchise they have known through Game cartridges, Manga, Animated television and light books, however, the core mechanics are unpolished and make it difficult for a player to acclimatize to, and understand the game rules. While in battle, the camera circles around the player—an attempt it would seem at portraying the animated televised battles, however the camera turns too quickly and the Pokémon are often outside of the camera’s lens. The player may start to feel motion sick. At times, the camera freezes, and the player cannot see the battle but is left to mindlessly press the “fight” button like they would in the game. My expectations were high: I wanted to see my Pokémon battle for ‘real’, like in the animated show. Additionally, the game made it difficult to level up one’s Pokémon. In my experience on these servers, once the player “spawns” onto the server they are given only one level five Pokémon and then stranded in an area with other Pokémon ranging in levels between 1 and 100, with most at around level 40. The player has almost no way of leveling up naturally but must contend with using a “warp” (if there are any) that brings them to another area where they can kill Magickarps (a fish Pokémon with no battle moves except “splash” that has no effect) to level up.

Visually, the environment lead the player towards a new and different experience of the Pokémon franchise they have known through Game cartridges, Manga, Animated television and light books, however, the core mechanics are unpolished and make it difficult for a player to acclimatize to, and understand the game rules. While in battle, the camera circles around the player—an attempt it would seem at portraying the animated televised battles, however the camera turns too quickly and the Pokémon are often outside of the camera’s lens. The player may start to feel motion sick. At times, the camera freezes, and the player cannot see the battle but is left to mindlessly press the “fight” button like they would in the game. My expectations were high: I wanted to see my Pokémon battle for ‘real’, like in the animated show. Additionally, the game made it difficult to level up one’s Pokémon. In my experience on these servers, once the player “spawns” onto the server they are given only one level five Pokémon and then stranded in an area with other Pokémon ranging in levels between 1 and 100, with most at around level 40. The player has almost no way of leveling up naturally but must contend with using a “warp” (if there are any) that brings them to another area where they can kill Magickarps (a fish Pokémon with no battle moves except “splash” that has no effect) to level up.

I found it easier to access the universe of online Minecraft Pokémon with a friend. We were able to battle each other and in so doing, level up our Pokémon. In this way, the servers can be said to have unconsciously recreated the narratives of the Game, Anime and Manga. In each media, the different main characters face an antagonist—their childhood rival, and through battling with each other they learn to overcome obstacles and gain experience. Without my friend, I might have been unable to obtain a level high enough to venture into the woods. I would have been stuck waiting for another new player to spawn and battling with them—and perhaps this is what the server administrators intended, however I am not persuaded that this was their intent.

Most of the servers I tried appeared to use the same models, skins and interface codes. What appears more plausible to me is that the server administrators obtained these player-generated objects and included them into their own servers without adding any additional codes. In my view, a programmer who has the necessary experience to fully rendered 3D models and change a games core mechanics (Pokémon battles), should also be able to adjust and stabilize the battle camera, and arrange Pokémon spawn points strategically by levels to allow new players to advance in the game and experience a better sense of immersion.

I wanted this server’s environment to mirror that of the franchise world—with the towns I knew, the same Gym locations and with Pokémons distributed by level. While the first server I tried had Pokémon, a battle arena and a Pokémon center, I found that I was just playing Minecraft with Pokémon in it and not actually playing a Minecraft version of Pokémon. In the second server, I felt like the environment better approximated the series, the players where more helpful and, adding a youtube playlist of Pokémon music (including battle music from the game), I felt like I was interacting more closely with the world of Pokémon. I believe a truer rendition would consider these ideas and create a world that is more easily open to player generated narratives. Of course, as Jenkins explains in his own work, by writing this down I have abdicated my role as overseer: these are only my own selfish desires, and attributes I deem important to Pokémon (Jenkins 128).

Battle sequence. It has the same interface as that of the game. Notice that the Pokemon is merged with my avatar

Part 2:

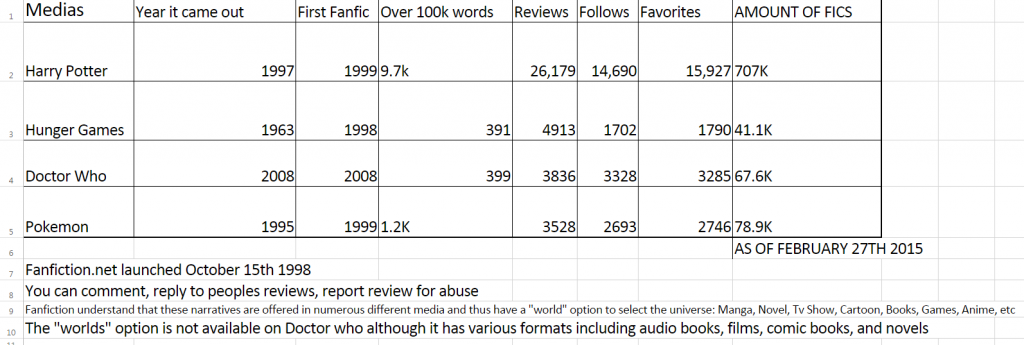

In chapter 3 “Searching for the Origami Unicorn” of Convergence Culture, Henry Jenkins explores the Matrix as a primary origin for transmedia storytelling. The western world was interested in transmedia products such as the Japanese Pokemon franchise that launched in English a year before the Matrix film. He believes that it is around this time, 1998-1999 that children began to “learn to inhabit the new kinds of social and cultural structures” (Jenkins 128), and that “kids who grew up in this media-mix culture would produce new kinds of media as transmedia storytelling becomes more intuitive” (Jenkins 130).

Children born today learn to use smart phones and tablets increasingly early. I recently saw a friend’s two year old child who owned his own iPad and was capable of surfing YouTube to find his favorite songs. We are in an era where we are surrounded by media, and have limitless knowledge at our fingertips.

With the internet comes the ability to express our own opinions on media publically to thousands if not millions of other fans. Fans have the capacity to meet other fans from different countries and speculate together. To form ideas and have them vaporized on the internet. We are no longer restricted to the few in our class rooms, homes and neighborhoods, we have the capacity of engaging in discourses about our favorite media with fans from all parts of the world. While Jenkins might root Transmedia as a story that “unfolds across multiple media platforms, with each new text making a distinctive and valuable contribution to the whole” (Jenkins 96) I would argue that the internet has added an additional clause: fan contribution.

When talking about The Matrix, Jenkins explains that “many fans expressed disappointment because their own theories about the world of The Matrix were more rich and nuanced that anything they ever saw on the screen” (Jenkins 96). Today, our society feels entitled to their opinions, to challenge narratives, and distort and reconstruct them to fit their own ideas. These opinions can no longer be ignored as they clutter the internet. We as a people want a say in the narratives we read, that we watch, and that we play. The internet promotes and facilitates this desire, and so I would suggest that Transmedia narratives did not originate only with franchises such as The Matrix, but also through the prevalence of the internet in popular culture and this consumers desire.

To get back to my experience with Pokemon I will now turn to how a player/consumer re-invention of Pokémon contribute to Transmedia narratives. I previously stated that I felt disappointed with the mechanics in the different servers. I felt like the servers lacked key points that made Pokémon Pokémon. Steinkuehler explains that “something must guide an individual’s sense making. This ‘something’ is (often tacit) assumptions about how the world “works,” assumptions that hang together to form ‘cultural models’” (Steinkuehler 40). I think this idea can be extended to the Pokémon franchise: those who have read the manga, played the games, and watched the show have a sense of what the ‘real’ Pokémon world is like: how it should work. Similarly, in “The Art of Contested Spaces” Squire and Jenkins argue that there are two different kinds of games one that is realistic and one that is immersive, “the realistic elements contribute to our sense of being there, whereas various forms of exaggeration ‘perfect’ the real world experience, making it even more exciting” (np). The Pokémon server’s felt ‘realistic’ as they emulate the different geographical regions of the Pokémon world, iconic land marks and had 3D Pokémon creatures. However, the servers do not exaggerate past these realistic points, and in so doing they limit the possibility for transmedia narratives to occur. That is not to say that it cannot do so, for I believe the possibility is there. As it stands, these servers are ripe for transmedia narratives, but are lagging behind, missing just a few crucial elements to emulate the feeling of Pokémon.

Squire and Jenkins explains that one of the major breakthrough in gaming came with “The shift from the top-down maps of Civilization to the through-the-gunsights perspective of the shooters [that] suggests a much more immediate, moment by moment, participation in the struggle for spatial dominance” (Squire and Jenkins). Like Civilization, Pokemon is has a top-down model. Players are trying to create their own first person version of the game that suggested to me that they want to embody their avatars in a way that a top-down model does not allow. They want to become the character. We can clearly see this in the number of fan fiction consumers create, and the amount of fans who read and enjoy them (see table below). They do not want to feel like they are in the game. And while I have not found any suitable Pokemon game server that could create an ongoing dialogue, I have found an exemplary one in “Potterworld”, a Harry Potter Minecraft server. This server goes beyond recreating the iconic structures of the Harry Potter world, but bring the player directly into this world. The player attends Hogwarts, must correspond with their house prefect, attend actual classes (and obey rules such as using commands to lift up their hands before speaking) and can only advance through the system by passing their courses and graduating. They can even try out for the sports team. Seeing this server, I know it is possible for players, for consumers, and not just franchise owners, to create ongoing transmedia narratives.

The everyday Joe wants his or her word heard, their story told, and their own real sense of being there, and they can achieve this through the internet, through their own comics, their own YouTube videos, games, fanfiction, etc. Today more than ever, fan-based creations play a role in how we interact with media. We cannot ignore the 9.7k fan fiction that have over 100k words each, nor can we ignore or discredit fan-authors who have over 26k reviews, 14k followers and 15k favorites (Harry Potter, Fanfiction.net, 27/02/2015).

Conclusion

“As players engage more directly in the design process, the line between gamers and designers begins to dissolve” (Squire and Jenkins). With the internet, consumers have the ability to build on pre-existing narrative. The amount of people that flock to the Pokémon and Harry Potter Minecraft servers, and the amount of fanfictions speak of our enthusiasm and desire to be a part of our favorite franchises. We now have the ability to recreate scenes from films or novels, to explore options the author did not include, to create our own narratives. One example of this desire is seen clearly in the manic craze surrounding Fifty Shades of Grey, a book series that started out as a Twilight fan fiction.

-Answers I sought in this play-through-

- What does it mean to impose an existing fictional structure on a game (like Minecraft) that has very little of its own?

- How do civility and the formation of rules create environments that are “true” to existing fictional narratives?

- How are video game narratives different than “fan fiction”, which also creates new dialogues between reader and established media?

- What does this interplay between player and media reveal?

- Can games force us to rethink the narrative models that we have inherited for discussing literature?

Sources

- Jenkins, Henry, and Kurt Squire. “The Art of Contested Spaces.”

- Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture : Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

- Carey, James W. “A Cultural Approach to Communication.” [Chapter 1.] Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society. Media and Popular Culture. Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1989.

- Steinkuehler, Constance A. “Massively Multiplayer Online Video Gaming as Participation in a Discourse.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 13.1 (2006): 38-52. Web. 12 Jan 2015.

- Thorhauge, Anne Mette. “The Rules of the Game—The Rules of the Player.” Games and Culture 8.6 (2013): 371-391. SAGE. Web. 20 December 2014.

MINECRAFT SERVERS

POKEMON

- spark.thedestinymc.com

- johto.pixelmoncraft.com

HARRY POTTER

to see some of this world, view the website, its class schedule, and this promo video