Harry Potter: Towards Fan-made transmedia…or not?

In my last week note I looked at fan made Pokémon Minecraft servers and their inability to portray a realistic depiction of any of the Pokémon medias including, but not limited to, the game, the anime, and the manga. The fan games, I argued, did not have the competency to create fully functional environments, which was a detriment to the feeling of immersion. The battle system, level distribution on the map, and the controls removed our ability to remain immersed in the environment as we were constantly being reminded of its errors. This time my focus is on a Minecraft mod called Potterworld that is based on JK Rowling’s Harry Potter. I previously argued that this server goes beyond recreating the iconic structures of the Harry Potter world, and that it brings the player directly into this world. However, while it does create a more immersive experience, the player must suspend their belief of the real narrative.

What makes this mod stand apart from other Harry Potter servers (and many Minecraft ones) is not only the beauty and picturesque perfection of the scenic elements, but the shear amount of moderators. The game works well because it is brilliantly created, and well managed. While it does allow some dialogue and continuation of the film and novel narrative, it undeniably falls short.

The Server and Ranking Up

This server boast a staffed of over 70 members, including professors, prefects, developers, architects and the headmaster. Members must apply for these positions after having completed their courses at Hogwarts, or for the developing team, a portfolio of work done using various programs. For example, the Potterworld FAQ link includes this description of the stated responsibilities of a prefect .

Additionally, players can view the extended list of requirements to become a developer, or other staff members, listed afterwards. The server administrator expects strong candidates with experience to help create this environment and maintain it. And this, with no cash incentive listed.

To advance as a player in this server, one must attend class, perform well and pass competency examinations. Upon successful completion of the examination, the student can move up the rank to the next level and so on and so forth until they graduate. At that point, they may apply to become professors, prefects, or decide to become Aurors or Deatheaters, etc.

Creating an area for extrinsic narratives?

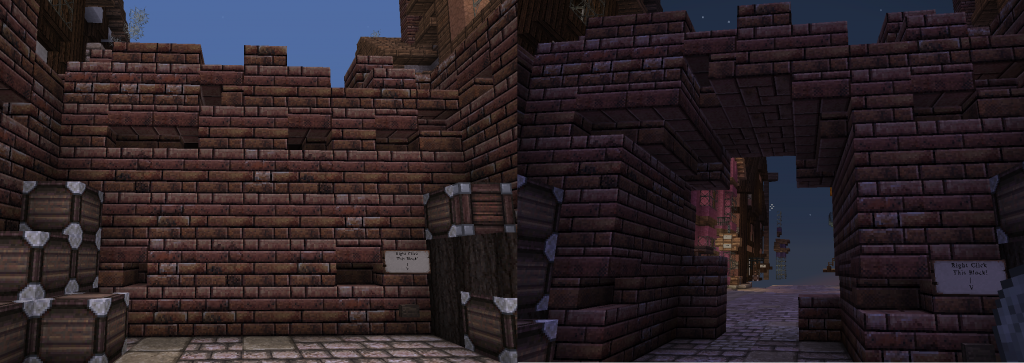

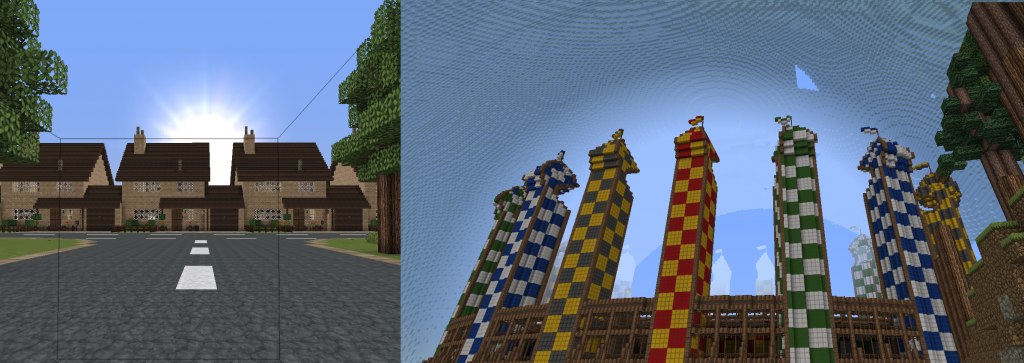

Kurt Squire and Henry Jenkins, renown game researchers, explains “everything there [in the game] was put on the screen for some purpose – shaping the game play or contributing to the mood and atmosphere or encouraging performance, playfulness, competition, or collaboration. If games tell stories, they do so by organizing spatial features” (Jenkens & Squire 1). Potterworld brings “Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry” to life through the use of Minecraft. The server uses plugins to change the look of the regular game and create environments that look incredibly similar to the film version. This is due in part to Minecraft being a sandbox, where one can create anything one wants, but also the sheer fan devotion. The staff’s ability to recreate the “Harry Potter” environments encourages the players to role-play—interacting with the game as though they themselves really attended the school and creating their own narratives with the help of other players. While players can role-play using messaging software such as Skype or through email, this server allows players to interact in a familiar world and create their own custom avatars that will be able to navigate and explore the world. It works because “the game constructs the story time as synchronous with narrative time and reading/viewing time: the story time is now” (Juul 7). This allows the players to feel more immersed than they would using messaging software and allows them to interact differently than “fan fiction”.

While “fan fiction” allows writers to create their own continuation of a series and to explore new grounds, it remains something that is more personal than an online game server. The author can decide not to read reviews or acknowledge suggestions and instead, write what they desire. On a public server, one never knows what will happen. The game allows the player to imagine not only what it would look and sound like to live in the Harry Potter universe, but also to see and experience it for themselves from a third person perspective; “the result is not realism but rather immersiveness” (Jenkins & Squire 6). The third person view allows the player to interact with the environment and players more directly. They are their avatars. This is their life.

Other Player Experienced

Having played on the server myself, I wondered how other players – notably those more interested in “Harry Potter”—would feel about the server. I had fellow student and game researcher Saeed Afzal play the game at Concordia’s TAG facilities.

“My experience with the Potterworld server, though brief, was rich and immersive. Through the use of mods, texture packs, written narratives, and interface changes, the creators managed to transform Minecraft into a nearly unrecognizable version of itself, one that simulated the world of Harry Potter in a number of sophisticated ways”

He explains that he had a positive overall experience in seeing and interacting with the architectural design of the environment from a third-person view. He explains that the buildings were “amazingly well done and followed very closely the designs from the Harry Potter movies”.

Everything from tapping on the wall of the Leaky Cauldron, getting your wizarding robes, and taking the train to Hogwarts was included. While they could have chosen to just drop the players straight into Hogwarts, this preamble added a richness to the narrative and another layer of immersion.

Afzal has previous experience playing licenced Harry Potter games, but said he felt more excitement in playing on this server:

He felt awed when he saw Hogwarts for the first time and explain that the beauty of the server and its mechanic thrilled him.

You feel less like a Minecraft player and more like an actual resident of the Harry Potter universe. Having played commercial Harry Potter games in the past, I can say that my favourite parts of those games were always when the player (usually embodying the character Harry Potter) was allowed to roam the grounds of Hogwarts and attend classes in whichever order they pleased. The gameplay during those points in the story was decidedly open-ended and light on plot progression, allowing the player to truly experience a ‘normal’ day as a Hogwarts student. This server aims to embody that experience, without the contrivances of the main series’ narrative – you get to simply be immersed in the world of Hogwarts and allow your own emergent narratives to blossom.

(Afzal, March 29th 2015)

Although the server does not boast a direct story line as the commercial games do, the server has since begun hosting live events where students—not Harry Potter and his friends—can take on the Dark Lord, protect Hogwarts and save their headmaster from death. These events are posted on their website’s main page. See the comments to view player enthusiasm.

On the other hand, while the server is beautifully crafted, it still falls shorts— it fails to illustrate an ongoing trans-media narrative. The server is more akin to “The Sims”, simulating the world of “Harry Potter,” and not necessarily a continuation of the narrative.

Narrative and Simulation

The Potterworld server is easily capable of functioning as a set up for multi-player role-playing. Players are capable of using the server, and all of its plugins, as tools for creating their own player generated narratives. They can enact the rivalry between the different factions, can duel, and can play the role of regular Hogwarts students, professors, and enemies—anything they can imagine. The player can even decide to find a job, rent a house or shop, or even buy a home thanks to the wealth system which uses the famous Harry Potter coins. The players are not forced to participate in the actual courses; however if they do not, they cannot advance in society. This brings up questions of ideology and of what this server depicts as a successful witch/wizard: one must absolutely participate in courses, study, pass and obey their superiors to succeed in the world and be more than just a “muggle”. The world closely resembles our own world in that players interact realistically with each other according to rules they would have learned in schools: raise your hand before speaking in class, be respectful towards other students and staff, do not vandalize, etc. Players can use these environments to “do their own dramatic reenactments of scenes from the movie or to create, gasp, their own ‘fanfiction’” (Jenkins 165). The rules allow them to participate in the narrative on a much deeper level: they know what to expect, and staff members will deal with those who breach protocol (“prefects”, “Staff”, “Professor” or the “Headmaster” himself). By naming the moderators according to the franchise itself, the game allows the players to feel more immersed and so when they have a problem, players need not ask for a moderator, but for a “prefect” to come and settle a dispute, all the while remaining immersed in their fictive narrative. This server, to rephrase Jenkins on the Star Wars game, shows “what life would be like” for a witch/wizard attending Hogwarts (Jenkins 106).

However, many factors ruin this sense of immersion. The game itself is a simulation that relies on the players’ knowledge of the franchise. It is this “familiarity with [the] basic plot structure [that] allows script writers to skip over transitional or expository sequences, throwing us directly into the heart of the action” (Jenkins 120). But by doing so, it removes the “real” narrative as seen in the books and films. The player is left with clay that they can then mold to create their own narratives.

Other than being a simulation, the game demands that the player overlook certain game mechanics. The server is huge and can host over 300 players at the same time. The sheer size of each map and players causes extreme lag (player avatar lag and block lag). When a player goes from one map to another it can take several minutes before the scenery appears. Meanwhile, the avatar is sluggish and the screen glitches. This even happens with a higher-end gaming desktop. And if the player tries to explore out of the map bounds, they walk into invisible walls that cannot be broken down. Another glaring issue, that players do not appear to notice, is the course system. To find the dates and times of classes, the student-player must go to the official website and check the schedule of class. This creates a feeling compatible to that of attending a “real” online course. There are also a particular set of rules for attending classes that one can obtain from the website:

To experience Potterworld completely, the student must frequent the website as much as the game server for rules, new plugins and news about the live events happening around campus.

In addition, the student must attend class and do the required homework and exams to pass and move on to the next level. To go to the class the player must either click a link that appears in the chat box or go to a sign that brings them there. It would have been more realistic (both to the Harry Potter world, the player-narratives, and the online Minecraft school experience) if the magnificent structure that looks like Hogwarts also had actual class rooms with doors instead of a sign system (opening the classroom door for instance could have been the portal to the classroom map).

Another problem is the way in which students communicate. Video game scholar Drachen suggests that researchers should study communicative patterns to notice when players are most immersed (Drachen 34). In the real world, students can only hear those closest to them and can thus have private conversations (or listen to gossip). In Potterworld, there are so many players typing at once that it is easy for a message to be overlooked. Even whispering (sending someone a message only they can see) is difficult as the text can be lost in the flow of other comments. A way to offshoot this problem would be to create groups with friends and use a voice-based application such as Skype to communicate. However, if the player also wants to interact with other players outside of their group, it could create a schism between the two messaging systems.

For the moment, when there are many people using the chat box, it can become difficult to communicate with the on-site prefect or staff member if a problem occurs. The player could just head to the website and file a complaint directly – but again, this ruins the immersion. My own experience with prefects has been good: when you first arrive on the server, you are classified as a “muggle” and the prefect’s job is to come and escort you to Hogwarts where you will be sorted and then be left to your own devices. They maintain a high level of communication, constantly making sure that you are “ok” and to “follow” them. However, one must keep their eyes fixed on the chat box, or they could miss a vital step.

Another interesting factor in this server is the ability to turn play into work that the players want to do—and apply to do. “Staff” members are no longer just players, but workers. Yee brilliantly says “Ultimately, the blurring of work and play begs the question—what does fun really mean?” (Yee 71). The server administrators have specifically changed the names and roles of moderators to create a form of player-labour. The player is happy as they are “prefects”, elite members of the Harry Potter world – and they take on the tasks as set in the books and films. They are thus playing at working: helping other players as their position demands, taking difficult decisions and generally making sure players act according to the established rules.

The Server Works Unconsciously for the Corporation

While the system does have flaws that make it difficult to classify as a trans-media narrative, it does continue to support it. Jenkins’ states “any given product is a point of entry into the franchise as a whole. Reading across the media sustains a depth of experience that motivates more consumption” (Jenkins 96). By playing on this server and sharing it with friends, players are unconscious consumers working for the company by “offering new levels of insight and experience [that] refreshes the franchise and sustains consumer loyalty” (Jenkins 96). Fan-fiction and player-created servers create more products that fans may consume, keeping them interested and susceptible to the franchise. The fans keep the franchise and narrative alive, allowing for the possibility of new narratives to surface in the future (J.K. Rowling has stated the possibility of new stories in the Harry Potter universe). These fans unknowingly create a market where the franchises can easily determine the viability of new projects. If franchise owners know that thousands of fans consume fan fiction and create their own servers to play those narratives, perhaps they will create new information in the forms of manuals, character sheets, early drafts of the books, and new toys such as plushies, games, etc. “What’s clear” explains Yee, “is that video games are blurring the boundaries between work and play very rapidly” (Yee 70).

Conclusion

In the end, this server is amazing and really makes the player feel like they are immersed in the world of Harry Potter. However, it is a simulation of going to school that teaches certain ideologies about school and society. In effect, the player is not playing a game, but playing at being a student and living in a different world. The maps are well constructed and reflect what players would have seen in the films. However, the sense of immersion is easily broken when players go from one map to another—the screen, world, and avatar lag—reminding the player that they are indeed playing on a server. To attend courses one must click links or signs, and the primary method of communication is always backlogged thanks to the three hundred players that can play at once. Bogost has said “We ought not to be satisfied. That’s the price of getting to make a living studying television, or videogames, or even Shakespeare” (Bogost np). But if we are not to ever be satisfied, we will never reach an end—we will always find fault with any aspect of media. Thus, is it even possible to create ongoing narratives that smoothly run from one media to another? Can the fan ever achieve this without the franchise’s backing? If our job is always to dig deeper and never be satisfied, won’t we always come up with reasons why something does not work? In all cases, the server has more chance than the Pokémon server at creating a trans-media narrative, but leads to questions about play-labour. Jenkins explains that media producers can obtain the most fan loyalty when they allow them (the fans) to have a part in the creation of the trans-media narratives “giving them some stake in the survival of the franchise […] creating a space where they can make their own creative contributions, and recognizing the best work that emerges” (Jenkins 168). These spaces can become “places where diverse groups of individuals with shared interests join together, where groups must negotiate norms, where novices are mentored by more experienced community members, where teamwork enables all to benefit from the different skills of group members, and where collective problem solving leads to collective intelligence” (Kahne 7). By allowing consumers to create their own spaces, corporations only further their interest: the players can feel included and part of the community, and will continue to consume whatever the corporation puts out in the market. Thus, fan created medias generate interest that keeps the fans entertained and thus helps prologue the franchise.

Bogost, Ian. “Against Aca-Fandom.” Bogost. 29 July 2010. Web. 1 April 2015.

Drachen, Anders, and Jonas Heide Smith. “Player Talk-The Functions of Communication in Multiplayer Role-Playing Games.” ACM Computers in Entertainment 6.4 (Dec 2008): 1-36. Google Scholar. Web. 2 January 2015.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture : Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

Jenkins, Henry, and Kurt Squire. “The Art of Contested Spaces.”

Juul, Jesper. “Games Telling Stories? A Brief Note on Games and Narratives.” Game Studies 1.1 (July 2001).

Kahne, Joseph. The civic potential of video games. MIT Press, 2008.

Yee, Nick. “The Labor of Fun How Video Games Blur the Boundaries of Work and Play.” Games and Culture 1.1 (2006): 68-71.