Probe 1: Fan-fiction and Foucault – “What is an Author?”

Specifically, what is an author in contemporary, 21st century society? We are living in a time where anyone can access and circulate text through the web, making it easier to reach target audiences and group together people that have similar interests.

Are people who write fiction online “authors”? They circulate text and create fiction, but are they “real” authors? Consider sites such as fictionpress.com where writers post their original free-to-read stories, and sites like amazon.ca and barnesandnoble.com that allow people to publish and sell their own books online. A good example would be the self-published writer Amanda Hocking who wrote an online only book series titled “My Blood Approves”. The book is only available for purchase as an e-book and costs under $1.00. What is interesting is that when I first found this book, it was free to read. Today, the books have gained more popularity and the author has begun to publish paperback books.

A similar case occurred with E.L. Jame’s “Fifty Shades of Grey” which started out as “Twilight” fan-fiction, but has since obtained its own, exclusive fan base.

So what is an author? Are you an author when you write books and release them to the public? Or is it only when you create printed books and sell them? Do you have to make a living off your texts to be considered an “author”? Additionally, what do we call “authors” that create free-to-read Fan-fiction, fiction created by fans based on pre-constructed text?

With the Internet, how can “real” authors maintain authorial power over their texts? Once released to the public anyone is free to interpret and to imagine new scenarios as they like. Problems concerning plagiarism and copyright laws arise when these fan-authors write down their ideas and publish them on sites such as Fanfiction.net.

My Focus will henceforth look at fan-fiction and specifically Harry Potter fanfiction.

“ Once the Author is removed, the claim to decipher a text becomes quite futile. To give a text an Author is to impose a limit on that text […] The reader is the space on which all the quotations that make up a writing are inscribed without any of them being lost […] the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author. (Barthe 147-148)

Fan-fiction sites such www.hpfanficarchive.com (Harry Potter Fanfic Archive ) and fanftion.net are interesting to handle:

Harry Potter Fanfic Archive calls itself an “archive”.

Both call their writers “authors” instead of “fan-fiction author” or “contributor”. They allow members to comment and “favorite” stories. The site also lists the “published” dates and completed dates and whether the story is “in progress” or “complete”.

It is interesting to note that the use of words such as “author” and the “publishing” date speaks to a form of “real” or “authentic” authorship. These sites validate fan-writers as authors of their own texts. Do these sites demonstrate fan desire; their desire to be part of the media franchise they love? To have a say in what happens to the narrative over time? It would appear that these site empower fan-writers by giving them such titles. Once established as a “good” writer, other fan-readers might take to calling them the author of “so-and-so fan-fiction” — displacing the “real” author and attributing new power to a fan-writer.

Foucault explains that “the author […] is a certain functional principle by which, in our culture, one limits, excludes, and chooses; in short, by which one impedes the free circulation, the free manipulation, the free composition, decomposition, and recomposition of fiction” (Foucault 230). However, fanfiction sites such as Fanfiction.net allow fans to create and distribute their own renditions/recreations/stories on any given, pre-created work. These sites circulate fan create fiction and allow readers to participate in the creation of new texts. “Authors” can obtain feedback through comments in the forms of ‘reviews’. Readers can ‘fav’ their favorite stories and add them to their favorite list. Fanfiction.net allows fans to distribute, preserve, and share with their communities (“fandom”) their own works for validation. The site becomes a digital archive, not of published works, but of works based of off other works.

Jk Rowling wrote an average of 155,000 words per book while writing bestselling novel series “Harry Potter”. What made her an “author”? Is it the fact that she put her thoughts into words and sold them on paper, or the fact that she created a story? Or, alternatively, is it something else entirely?

Harry Potter

The Philosopher’s Stone – 76,944

The Chamber of Secrets – 85,141

The Prisoner of Azkaban – 107,253

The Goblet of Fire – 190,637

The Order of the Phoenix – 257,045

The Half-Blood Prince – 168,923

The Deathly Hallows – Approximately 198,227

http://www.betterstorytelling.net/thebasics/storylength.html

What does it mean when fan-fiction is as long (or longer) than the original fiction it emulates; that it is free-to-read and easily accessible to the masses?

Fanfiction.net

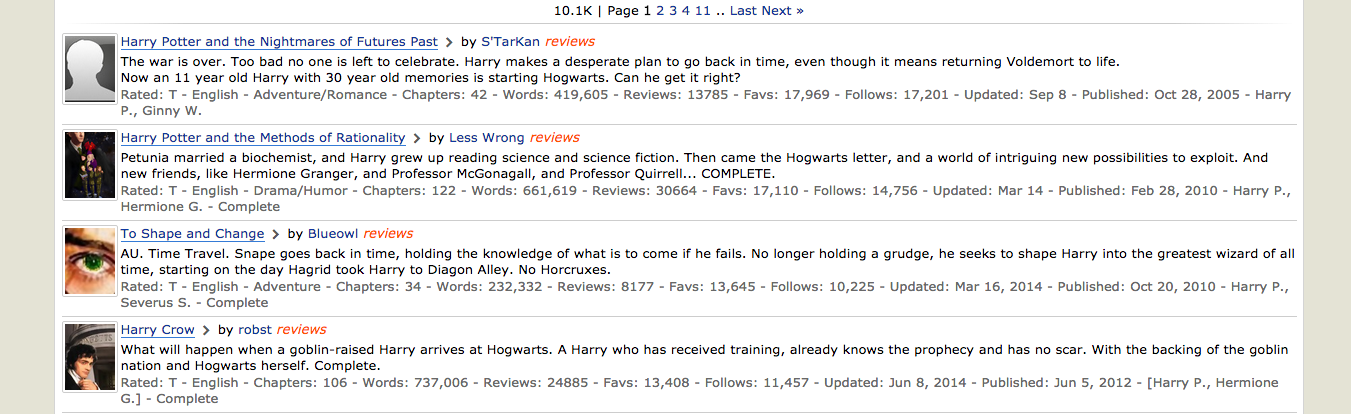

Fanfiction.net houses over 10.1k Harry Potter fan-fictions with over 100k words: there is over 10.1k book length fan-fiction about Harry Potter on Fanfiction.net alone. These are the top “favs” Harry Potter fan-fiction. Fanfiction.net allows registered members to “favorite” a story if they like it. As you will notice, these have well over two hundred thousand (200k) words – these are larger than Jk’s last Harry Potter book. Additionally, Robst’s “Harry Crow” has over 700,000 words (the length of approximately the first 5 books combined!), is “complete”, and has over twenty four thousand comments (24k) and over thirteen thousand “Favs” (13k).

Understand; one can read a fan-fiction without having an account, therefore, the thirteen thousand “favs” can be understood as thirteen thousand different registered readers. Without counting those that do not have an account but who have read and enjoyed the fiction, we can still understand the impact of fan-fiction online. Readers enjoy reading fan-fiction. Writers enjoy creating stories that investigate author-gaps, or alternate universes.

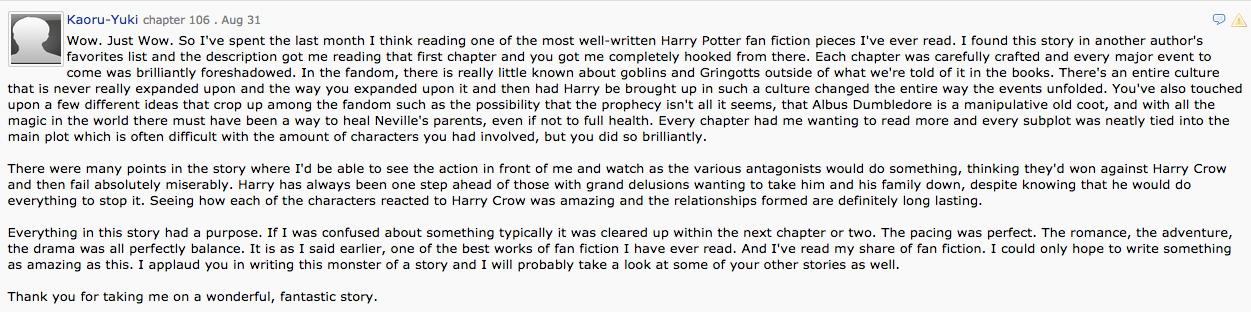

Robst’s explores the lives of Goblin’s in Harry Potter—something that J.K. Rowling did not. Robst created new mythology and investigated the idea of a Harry Potter that did not live with his uncle and aunt, but who lived with Goblins. The story looks at the fundamental rules of being a “Goblin” versus a “Wizard”, and the tension and animosity between them.

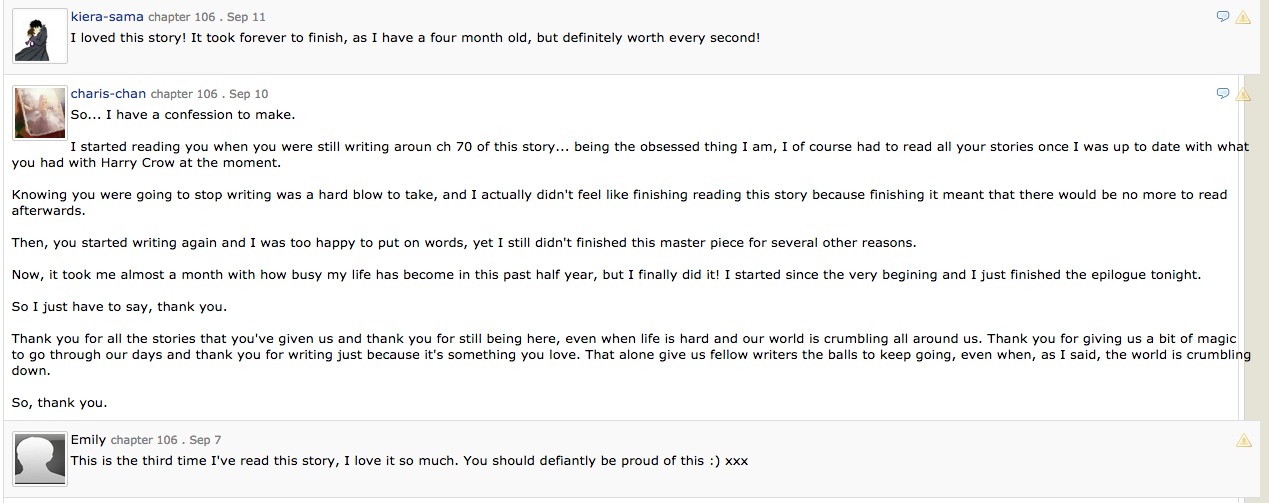

“Harry Crow”’s comment section is full of praise. One reader describes it as a “master piece [sic]” (Charis-chan). Readers enjoy the fact that Robst explores areas of J.k. Rowling’s world that she left unexplored. Interestingly, these readers employ similar dictions of praise as they would a “real” author, using words such as masterpiece, and stating their enjoyment of the work, the praise of the amount of effort it took to create the work, and thankfulness that the writer finished the work. However, Robst is very much a fan-fiction author. So what does Robst’s fan-fiction mean in unison, or parallel to the “real” Harry Potter? What does it do to, and for, J.k. Rowling? What does it mean that Robst created a “masterpiece” ?

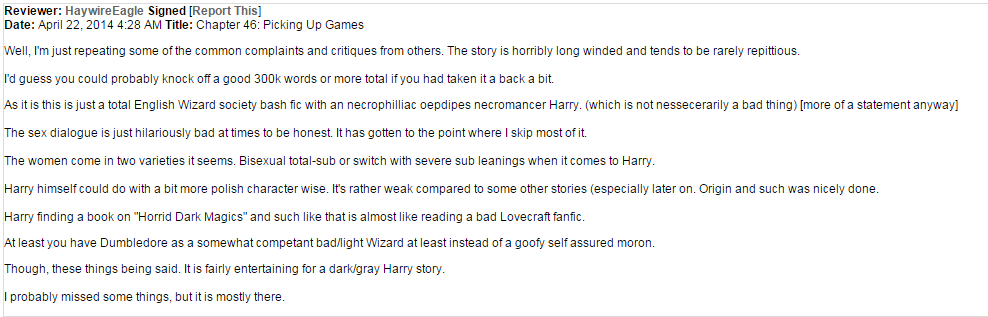

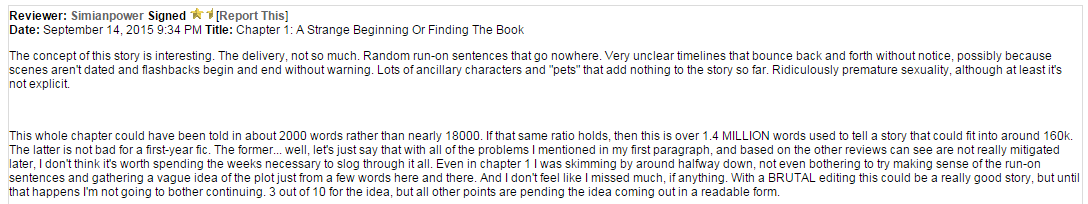

While these stories do pose multiple questions regarding authorship and validity, not all fan-fiction are created equally. Fan-fiction author SamStone’s story “Enter the Silver Flame” on Harrpy Potter Fanfic Archive, is over 1.4 million words long. However, compared to “Harry Crow” who has 24k comments and thousands of “favs” and half the amount of words, “Enter the Silver Flame” only has two hundred and thirty comments, with most complaining about the length, the grammar and many aspects of the story itself.

Should SamStone and Robst be considered “authors”? Should we considered one of them to be more of an “author” than the other based on the other stories they have written, the comments they have receive and their overall rating?

Copyrights

When Warner Bros bought the rights to Harry Potter, the company began sending cease and desist letters to fan-fiction authors, fan sites, and etc “on the grounds that they infringed on the studio’s intellectual property” (Jenkins 170). The fight was messy and included non-profit websites maintained by teenagers (www.dprophet.com) having to argue and defend themselves against the large corporation. In the end, the disputes were settled and Warner Bros allowed the sites to continue. Author J.K. Rowling later came out saying that she did not mind readers creating Harry Potter fan-fiction but that she wanted them to remain PG. Still, as Media scholar and professor Henry Jenkins’ puts it, “Nobody is sure whether fan fiction falls under current fair-use protections. Current copyright law simply doesn’t have a category for dealing with amateur creative expression” (Jenkins 189)

While Authors like J.K. Rowling, Meg Cabot, and E.L. James are ok with readers writing fan fictions (link: http://www.dailydot.com/culture/10-famous-authors-fanfiction/), other authors such as Anne Rice, Ursula K. Leguin, Diana Gabaldon see them as an attack, as illegal and “immoral”. These later authors have sparked a lot of conversion online.

Readers, those that consume and allow these writers to live on their writing, are also participating in this discourse. Fans want an area where they can talk about their fandom and create their own stories. They want to be heard – they want a say in how the story “ends” and will not sit back. When Jenkins explains that “the studios are going to have to accept (and actively promote) some basic distinctions: between commercial competition and amateur appropriation, between for-profit use and the barter economy of the web, between creative repurposing and piracy” (Jenkins 167) do we believe him? Do we see this as the possible death of “the author” as controlling, powerful source? Do we see this as the future of authorship?

Jenkins explains that media producers can obtain the most fan loyalty when they allow fans to have a part in their favorite media franchises. “Giving them some stake in the survival of the franchise […] creating a space where they can make their own creative contributions, and recognizing the best work that emerges” (Jenkins 168). Although Jenkins is referring to online games such as Star Wars, I find it is equally applicable to fan-fiction in general. Can allowing fans to ‘infringe’ on rights by writing their own fan fiction actually sustain relevance for a given work? Read: can it maintain social interest over time.

Perhaps more author’s like Orson Scott Card will finally come to terms with fan-fiction and use it to their advantage: “‘Every piece of fan fiction is an ad for my book,’ Mr. Card says. ‘What kind of idiot would I be to want that to disappear?’” he decided to give his loyal writers something to look forward to, something to legitimize their writing:“Fans will be able to submit their work to his Web site. The winning stories will be published as an anthology that will become part of the official “canon” of the “Ender’s Game” series.

If an author is (in a “limited sense”) “a person to whom the production of a text, a book, or a work can be legitimately attributed” (228), is fanfiction.net wrong in calling those who write “authors”? should they be “contributors”? What term could be best attributed to these fiction writers? Thieves? What gives these writers the power to call these fan-fiction their own? Why do they feel the need to demand that no one else use their ideas? In a future where authorship is irrelevant, Foucault considers new questions we will ask of literature: “what are the modes of existence of this discourse? […] where has it been used, how can it circulate, and who can appropriate it for himself” (230) – all these questions seem answered through fan-fiction. This growing, digital fandom living in a gigantic and forever growing archive—constantly mediating between the text, the author, the writer, the readers and the fandom.

Fans will continue to speculate and create their own renditions in order to fill the “gaps and breaches” that they conceive authors left behind. Whether author’s like it or not, fan-fiction has become part of the media industry. Acting as times as an after life, or delving into mysteries the author chose not to explore. Consider that many readers often feel a sense of loss at the end of a good book/movie/etc. Although we still operate within an author define and controlled discourse, fans can still find gaps and breaches in works that appeal to them and envision scenarios that could fill them. Earlier, I spoke about how fan generated fiction allows the free circulation of work—however, more often than not, fan-fiction authors will include a note in their first chapter, something akin to “All characters and story belong to [respective author or company]. Original characters and this story belong to me. Please do not redistribute or steal my ideas”. While fan-fiction might be a method of killing the author and it’s function, for the moment, fan writers cannot escape the notions of being an author—of possession control over their “own” work while also asserting that they are appropriating other people’s works in order to create their own stories. They want to manipulate someone else’s work, but fear their own being manipulated. So while fan-fiction sites allow the free distribution and circulation of fan-generated texts, it is still entrenched in the idea of the author as the proprietor and owner of text. The problem remain; what is an author and is it ethically, morally correct to actually “publish” fan-fiction online?

Even writing a work cited reference for a fan-fiction is complicated: how do you write it? There does not appear to be a standard way of writing one. Fan-fictions are becoming increasingly popular, should it have its own reference MLA guide?

Stay tuned for the class discussion where I will focus on these thoughts as well as:

- The “author function” at play

- K. Rowling’s male pseudonym: an attempt to escape her fame as the creator of Harry Potter by disassociating her name from her new work.

- Media tie in — killing the fan-fiction author?

- Fan-fiction writers and pseudonym’s – does this affect the text as much as the “real” author’s use of a pseudonym?

- The author’s word is law: bridge in fandom

- The text and it’s afterlife: film, adaption, remakes.

- Are TV shows adaption like “True Blood” simply fan-fiction of their original text?

Work cited and referenced

Jenkins, Henry. “Convergence Culture : Where Old and New Media Collide”. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

Robst. “Harry Crow.” Fanfiction.net. Jun 5, 2012. Based on J.k. Rowling’s Harry Potter. Web. https://www.fanfiction.net/s/8186071/1/Harry-Crow

“Book Post: How authors feel about fan-fiction.” Oh No They Didn’t. Livejournal, 19 April, 2012. Web. 19 September 2015.

Barthes, Rolland. “The Death of the Author.” Trans. Jean-Pierre Vernant. Web. Pdf. http://artsites.ucsc.edu/faculty/Gustafson/FILM 162.W10/readings/barthes.death.pdf

Tresca, Don. “Spellbound: An Analysis of Adult-Oriented Harry Potter Fanfiction.” Fan CULTure: Essays on Participatory Fandom in the 21st Century. Ed. Barton, Kristin M and Jonathan Malcom. USA: McFarland & Company. 36-46. Print.

Alter, Alexandra. “The Weird World of Fan Fiction.” Art & Entertainment. 14 June 2012. The Wall Street Journal. Web. 23 Sept. 2015. http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303734204577464411825970488

Harry Potter Fanfic Archive. http://www.hpfanficarchive.com/stories/reviews.php?type=ST&item=270

Foucault, Michel. What is an Author? Web. DropBox.

“Jk Rowling revealed as author of The Cuckoo’s Calling.” Entertainment & Arts. 14 July 2013. BBC. Web. 22 september 2015. http://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-23304181

Kee, Chera. “Translating Media.” The University of Southern California Journal of Film and Television Criticism. Spectator 30.1 (2010): 30-34. Web. 4 may 2015.