Are Brontë Studies Too Subjective?

Charlotte Brontë is a difficult author—not because her writing is dense or particularly ambiguous, but because a phenomenon that Lucasta Miller calls “The Brontë Myth” has made her difficult to study. In her book by the same name, Miller examines the cultural fascination with the Brontës’ writing and their lives through a study of the different biographies that have been published and re-interpretations of the Brontës in modern culture. Only this fascination doesn’t end with their most recent biography or film adaptation, but bleeds into scholarly criticism. To explain what I mean, I’m going to refer to an off-hand comment a professor once made about teaching Charlotte Brontë:

“You have to be careful when you teach the Brontës. Give your students too many biographical details and all their term papers will focus on the parallels between their lives and their writing.” — Dr. Tabitha Sparks

And the reasons are compelling: when you consider Charlotte Brontë’s final novel, Villette (1853), you quickly notice a crux of parallels between Brontë’s biography and the experiences of the main character, Lucy Snowe. Like Snowe, Brontë spent time living and teaching in Belgium, where she also had an affair, before returning to England. In fact, Villette is a rewritten version of Brontë’s first novel and semi-autobiography, The Professor (1857).

But just how much of recent scholarship on Villette uses Charlotte Brontë’s biography to ground their interpretations of her writing?

To answer this question, I surveyed recent criticism (published between 1995 and 2015) on Charlotte Brontë’s Villette. In order to ensure that I conducted a comprehensive survey of the critical field, I used coordinated searches of the MLAIB, ABELL and JSTOR databases using the subject terms “Brontë and Villette.” Then in a secondary search, I used the key terms “biograph* or autobiograph* or postcolonial* or material*” in an attempt to narrow down on the authors’ methodological approaches. As a result, I collected two critical essay collections, one book and 24 journal articles that make up the object of my analysis. To determine the main methodological approach of each author, I paid close attention to the articles’ abstracts, introductions and conclusions as well as examined patterns in the citations the authors used.

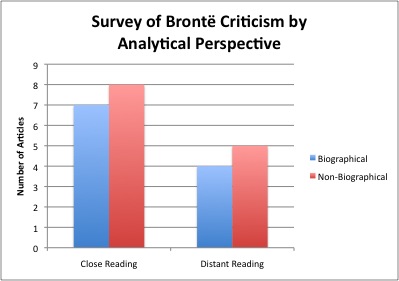

Of the 27 different articles I read, biographical details were used as the unique context or key evidence for argumentative reasoning in 14 examples (52%). But of remaining 13 articles, how many consider Villette in context? I then separated the articles according to whether they used a close reading or distant reading approach, as you can see in the figure below.

The articles designated “close reading” didn’t consider Brontë’s writing in context, either ideological or historical, but rather focused on interpreting the structure of Villette. In actual fact, the number of texts that engaged with a textual discussion of Brontë’s novel without basing their arguments on her biography only constituted 18.5% of my sample pool.

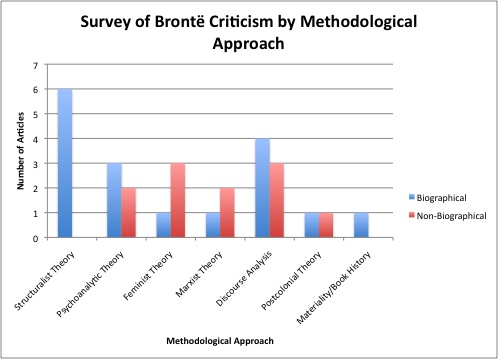

In figure 2, the texts are divided according to their main methodological approach. This graph shows how structuralist critics privileged biographical elements to ground their interpretations, while users of the other dominant methodological approach, discourse analysis, demonstrated both biographical and non-biographical arguments. While both these graphs allow us to visualize the spread of recent scholarship on Brontë’s Villette, they don’t necessarily make apparent the weight the articles attribute to Brontë’s biographical details. This requires a more qualitative analysis.

Many of the articles that used a biographical approach cite Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography of Charlotte Brontë, The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857), as well as some sections of Brontë’s personal correspondence, oftentimes as the sole evidence to contextualize their interpretations. In the introduction to The Brontë Sisters: Critical Assessments (1996), an essay collection that assembles book reviews and scholarship on the Brontës since the publication of their works, Eleanor McNees notes: “[poststructuralist] approaches run a different risk: that of making the novels secondary to the study of specific historical events. In the Brontës’ cases, this is an especially serious dilemma, because their works are so predominantly subjective” (8-9, my emphasis). This “subjective” approach uses biographical details to justify interpretations as “true” by demonstrating authorial intent. However, that authorial intent isn’t as straightforward to gauge as it would seem. In The Brontë Myth, Miller analyzes Gaskell’s biography and demonstrates just how constructed it is. Miller notes that Gaskell’s “hagiographic” (170) biography “redirected our attention towards the moving, dramatic, and uplifting aspects of [the Brontës’] lives” (57). Above all, Miller argues that Gaskell’s biography is inherently subjective and should be considered as a narrative:

It was not designed to celebrate the work but to exonerate and iconise the authors. The legend it laid down—three lonely sisters playing out their tragic destiny on the top of a windswept moor with a mad misanthrope father and doomed brother—was the result of the very particular mindset Gaskell brought to it. (57)

In this light, it’s troubling to consider just how much of Brontë criticism is centred on biographical details.

That being said, a few of the articles that quoted Gaskell’s biography also acknowledged their reliance on Brontë’s biographical details and attempted to compensate for it. In a footnote to her paper titled “Choseville: Brontë’s Villette and the Art of Bourgeois Interiority,” Eva Badowska clarifies that her paper “is part of a larger critical effort to demythologize Brontë studies” and cites The Brontë Myth (1522). Josephine McDonagh makes a similar statement in her own paper on provincialism in Villette:

This claim endorsed the view put forward by Gaskell in her biography, that the Brontës’ works were the unwitting products of their secluded and uncultured upbringing. Such a response to the Brontës characterizes much of the critical work on them, and forms part of what Lucasta Miller calls “The Brontë Myth.” (413-14)

These articles then compensate for their reliance on biographical details by demonstrating a citational diversity that has the effect of reducing the importance attached to individual sources. The most notable of these from the sample pool was Vlasta Vranjes’ “English Cosmopolitanism and/as Nationalism: The Great Exhibition, the Mid-Victorian Divorce Law Reform, and Brontë’s Villette” which cites 64 different primary and secondary texts in her discussion of Villette, including letters from Brontë’s contemporaries, parliamentary debates, contemporary news articles, scholarly books and journals from backgrounds of literary, historical and sociological criticism. This citational diversity is a hallmark of discourse analysis, which Robert de Beaugrand defines as “the cross-cultural study of stories and narratives” to “resituate language in these contexts” (128). This method of discourse analysis lends Vranjes a certain notion of objectivity by distancing the the figure of the author from the argument. To be clear, I am not claiming that discourse analysis is objective by nature, but rather the practice of engaging with a multitude of sources creates the impression of an objective perspective.

It would seem that these two approaches, one “subjective” and the other “objective,” are incompatible: one must either choose between studying the author as subject or studying the author as object (Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author”). However, Michel Foucault offers us a third possibility. In “What is an Author?,” he responds that this shift in focus, “intended to replace the privileged position of the author seem[s] to preserve that privilege and suppress the real meaning of his disappearance” (226). Instead, he argues that we must study the discursive relationship between the author and work (oeuvre), the “relationship (or non-relationship) with an author, and the different forms this relationship takes” (229). It’s important to note that when Foucault discusses the “author” he’s not referring to a historical person, but rather the “author function”:

an author’s name is not simply an element in a discourse (capable of being either subject or object, of being replaced by a pronoun, and the like); it performs a certain role with regard to narrative discourse, assuring a classificatory function. Such a name permits one to group together a certain number of texts, define them, differentiate them from and contrast them to others. In addition, it establishes a relationship among the texts. (227)

In the case of Brontë studies, it is quite clear that the author function has been conflated with the person of the author, but what impact has this had on the choice of methodology by scholars? Foucault argues that, “The author allows a limitation of the cancerous and dangerous proliferation of signification” (230) and allows for the definition of “true” interpretations via “authorial intent.” So far in my own research, I’ve found that the pursuit of an “authorized” reading amongst Brontë scholars has precluded any serious study of the materiality and the history of Villette in print. What other methodological approaches have been neglected?

Throughout this short discussion and survey of recent criticism on Charlotte Brontë’s Villette, I’ve considered the role an author plays in a critical context. While this analysis of writing on Brontë and Villette is by no means complete, I mean this to be the starting point for a longer discussion of our current notions of authorship. Specifically, how do these notions structure the kind of research that is possible. Some other questions to be considered are: How is this discursive relationship altered by anonymity? How does gender play a role in authorship? How has our understanding of authorship changed over time? What other critical lenses could be useful when considering the author question?

As these questions are enumerated and eventually answered, they’ll establish an active study of the author function in scholarly criticism.

Works Cited

Badowska, Eva. “Brontë’s ‘Villette’ and the Art of Bourgeois Interiority.” PMLA 120.5 (Oct. 2005): 1509-1523.

Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” The Book History Reader. Ed. David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery. New York: Routledge, 2002. 221-224.

Brontë, Charlotte. Villette. Ed. Kate Lawson. Peterborough, ON: Broadview, 2006.

——–. The Professor. Ed. Margaret Smith and Herbert Rosengarten. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1991.

De Beaugrand, Robert. “Discourse Analysis.” Contemporary Literary & Cultural Theory. Ed. Michael Groden, Martin Kreiswirth, and Imre Szeman. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 2012.

Foucault, Michel. “What is an Author?” The Book History Reader. Ed. David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery. New York: Routledge, 2002. 225-230.

Gaskell, Elizabeth. The Life of Charlotte Brontë. London: Dent, 1908.

McDonagh, Josephine. “Rethinking Provincialism in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Fiction: Our Village to Villette.” Victorian Studies 55.3 (Spring 2013): 399-424.

McNees, Ellen, ed. The Brontë Sisters: Critical Assessments. 4 vols. East Sussex: Helm Information Ltd., 1996.

Miller, Lucasta. The Brontë Myth. London: Vintage, 2002.

Sparks, Tabitha. “The Sensation Novel.” ENGL 405: Studies in the Nineteenth Century. McGill University, Montreal. 17 Nov. 2014. Lecture.

Vranjes, Vlasta. “English Cosmopolitanism and/as Nationalism: The Great Exhibition, the Mid-Victorian Divorce Law Reform, and Brontë’s Villette.” The Journal of British Studies 47.2 (April 2008): 324-347.

For a complete list of the works I examined in writing this probe, click read more.

Badowska, Eva. “Brontë’s ‘Villette’ and the Art of Bourgeois Interiority.” PMLA 120.5 (Oct. 2005): 1509-1523.

Bernstein, Sara T. “‘In This Same Gown of Shadow’: Functions of Fashion in Villette.” The Brontës in the World of the Arts. Ed. Sandra Hagan and Juliette Wells. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate, 2008. 149-167.

Braun, Gretchen. “‘A Great Back in the Common Course of Confession’: Narrating Loss in Charlotte Brontë’s Villette.” ELH 78:1 (2011): 189-212.

Buzard, James. “Outlandish Nationalism: Villette.” Disorienting Fiction: The Autoethnographic Work of Nineteenth-Century British Novels. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2005. 245-276.

Brent, Jessica. “Haunting Pictures, Missing Letters: Visual Displacement and Narrative Elision in Villette.” Novel: A Forum on Fiction 37:1-2 (2003): 86-111.

Carens, Timothy L. “Breaking the Idol of the Marriage Plot in Yeast and Villette.” Victorian Literature and Culture 38:2 (2010): 337-353.

Clarke, Michael M. “Charlotte Brontë’s Villette, Mid-Victorian Anti-Catholicism, and the Turn to Secularism.” ELH 78:4 (2011): 967-989.

Donovan, Julie. “Ireland in Charlotte Brontë’s Villette.” Irish University Review 44.2 (2014): 213-233.

Forsyth, Beverly. “The Two Faces of Lucy Snowe: A Study in Deviant Behaviour.” Studies in the Novel 29:1 (1997): 17-25.

Heady, Emily W. “‘Must I Render an Account?’: Genre and Self-Narration in Charlotte Brontë’s Villette.” Journal of Narrative Theory 36:3 (2006): 341-334.

Hodge, John. “Villette’s Compulsory Education.” SEL 45:4 (2005): 899-916.

Hughes, John. “The Affective World of Charlotte Brontë’s Villette.” SEL 40:4 (2000): 711-726.

Kent, Julia D. “‘Making the Prude’ in Charlotte Brontë’s Villette.” Partial Answers: Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas 8:2 (2010): 325-339.

Klotz, Michael. “Rearranging Furniture in Jane Eyre and Villette.” English Studies in Canada 31:1 (2005): 10-26.

Law, Jules. “There’s Something About Hyde.” Novel: A Forum on Fiction 42:3 (2009): 504-510.

Lawson, Kate; Shakinovsky, Lynn. “Fantasies of National Identification in Villette.” SEL 49:4 (2009): 925-944.

Litvak, Joseph. “Charlotte Brontë and the Scene of Instruction: Authority and Subversion in Villette.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 42.4 (Mar. 1988): 467-489.

Longmuir, Anne. “‘Reader, Perhaps You Were Never in Belgium?’: Negotiating British Identity in Charlotte Brontë’s The Professor and Villette.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 64:2 (2009): 163-188.

Mayer, Nancy. “Evasive Subjects: Emily Dickinson and Charlotte Brontë’s Lucy Snowe.” Emily Dickinson Journal 22:1 (2013): 74-94.

McDonagh, Josephine. “Rethinking Provincialism in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Fiction: Our Village to Villette.” Victorian Studies 55.3 (Spring 2013): 399-424.

Nestor, Pauline. “New Opportunities for Self-reflection and Self-fashioning: Women, Letters and the Novel in Mid-Victorian England.” Literature and History 19.2. 18-35.

Preston, Elizabeth. “Relational Reconsiderations: Reliability, Heterosexuality, and Narrative Authority in Villette.” Style 30:3 (1996): 386-408.

Surridge, Lisa. “‘Representing the Latent Vashti’: Theatricality in Charlotte Brontë’s Villette.” The Victorian Newsletter 87 (Spring 1995): 4-14.

Vranjes, Vlasta. “English Cosmopolitanism and/as Nationalism: The Great Exhibition, the Mid-Victorian Divorce Law Reform, and Brontë’s Villette.” The Journal of British Studies 47.2 (April 2008): 324-347.

Warhol, Robyn R. “Double Gender, Double Genre in Jane Eyre and Villette.” SEL 36:4 (1996): 857-875.

Wein, Toni. “Gothic Desire in Charlotte Brontë’s Villette.” SEL 39:4 (1999): 733-746.

Wong, Daniel. “Charlotte Brontë’s Villette and the Possibilities of a Postsecular Cosmopolitan Critique.” Journal of Victorian Culture 18:1. 1-16.

Yost, David. “A Tale of Three Lucys: Wordsworth and Brontë in Kincaid’s Antiguan Villette.” MELUS 31.2 (Summer 2006): 141-156.