Farber meets Foucault: A Probe

Writing is now linked to sacrifice and to the sacrifice of life itself; it is a voluntary obliteration of the self that does not require representation in books because it takes place in the everyday existence of the writer. Where a work had the duty of creating immortality, it now attains the right to kill, to become the murderer of its author. [1] ~ Michel Foucault, Language, Counter-memory, Practice

Let’s assume for a moment that we the starting point is a stage play with one sole Author. In an adaptation or translation of that play, who is the Author? Now what happens if there are multiple texts that are woven together? Who then is the Author? Is it the goal of both Author and Adaptor to disappear? Or is it the goal of the Adaptor to reincarnate the Author in his or her own work? Does the “play” that exists in an adaptation or translation fracture the seemlessness of the meaning and intention of an Author? If so, what does it expose? Does it expose the infrastructure of the theatre? The infrastructure of culture? Does it force us to look at our contemporary cultural episteme? Are we faced with the inability to look away from our own assumptions?

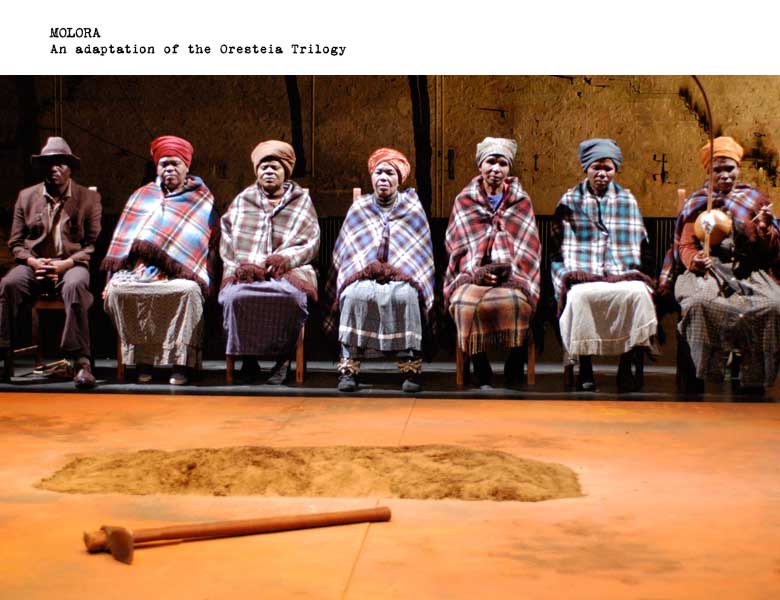

Molora[2], created (or composed) by Yael Farber, is an adaptation of the Oresteia Trilogy placed in the context of post-Apartheid South Africa in the midst of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission proceedings. Klytemnestra, a white woman, has killed her husband Agammemnon. Her daughter, Elektra, steals her brother Orestes away from the house and takes him to a nearby village. The children are mixed race, but are portrayed by black actors. Elektra endures seventeen years of torture as her mother tries to pry the location of her son from her daughter’s lips. She will not give in. Orestes returns. Elektra and Orestes plot their revenge against their mother, but when the moment arrives, Orestes cannot go through with it. Elektra, with the help of the chorus of women (played by the Ngqoko Cultural Group), relents and breaks the cycle of vengeance, offering instead her hand to her fallen mother.

In this play, Farber uses draws together text from Aeschylus’ Agammemnon and The Libation Bearers (Choephoroi), Sophocles’ Electra, and Euripides’ Elektra. She incorporates Xhosa and split-tone singing of the Ngqoko Cultural Group, based out of the region of Transkei. She utilises elements of traditional African storytelling as well as the testimonial from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission trials and winds them together with characters and techniques from the Greeks. But why? What effect does this have on our understanding of the story, or of both stories? What do we see that we wouldn’t have otherwise noticed if this were a new play rather than an adaptation?

Let’s first look at the physical playing space.

(image from http://www.cornellcollege.edu/classical_studies/lit/cla364-1-2006/01groupone/Scenery.htm)

In the mise en scène, Farber says, “This work should never be played on a raised stage behind a proscenium arch… Contact with the audience must be immediate and dynamic, with the audience complicit – experiencing the story as witnesses or participants in the room, rather than as voyeurs excluded from yet looking in on the world of the story.”[3] While she employs the same set up of raked audience with a flat playing surface (complete with an altar) as the Greeks, her intentions are widely different. The Greek amphitheatres were designed to maximize the seating capacity through sightlines and acoustic sensibility and privilege the nobility by seating them closer to the playing space. Farber, on the other hand, believes that this stage set up will create a relationship between audience and actor (or story) that is complicit and active. The audience is no longer allowed to disappear into the darkness of the traditional Western theatre houses of the proscenium arch. They must bear witness to the story. Having used this play as a teaching tool for text analysis classes, I know that this notion of active audience can make people uncomfortable. Why? We are a society that thrives on witnessing. Through posts on Facebook, Tweets on Twitter, pictures on Instagram, (etc.) we demand that the world around us witness our lives through social media. It is almost as if that witnessing is a requirement of being, and without it, without the acknowledgment (likes, thumbs up, retweets, comments) we are nothing. It seems to be, using Foucault’s term, to be the foundation of our cultural episteme[4]. So what is it about this idea of witnessing in Farber’s play that seems so radical? It is live. We cannot be anonymous. We can’t hide behind our digital selves and pretend we are something we are not. Witnessing requires consent and voluntary exposure of self on both the part of the actor and the audience. It requires seeing. Perhaps in Farber’s play her purpose or intention was not related to disappearance, but rather to exposure.

Let’s see if this theory holds true in the language of the script and production. Farber uses text from four different Greek plays. In the text itself she uses footnotes to cite the passages and acknowledge their Author. In this respect, we cannot avoid noticing or acknowledging the Author of these stanzas. But for her own words, for the lines of dialogue that are solely her creation, there are no footnotes. She writes in both English and Xhosa and there are no footnotes for text in either language. By publicly announcing the presence of the former Authors, is she purposefully turning the attention away from herself? Is she trying to disappear into the spaces between their text? In a production, of course, there are no footnotes displayed as subtitles. So the barriers between Authors becomes more permeable. The classical Greek passages become one singular voice (the dead white man perhaps?). By contrast, Farber’s writing becomes more evident. The play begins with the line “Ho laphalal’igazi. [Blood has been split here.]”[5] The first words uttered on stage in Molora are in Xhosa, followed swiftly by a verbal translation in English (marked by the square brackets). This Translator is a character in the play and this pattern of Xhosa being translated into English exists throughout the play. But it only ever goes one way. Nothing is translated from English into Xhosa. When we hear the Xhosa speech, we are very aware that there is a different voice from the Greeks in play. What then is the role of the translation? What does it do? Is it merely a mechanism to ensure the audience understands the text? If so, why use Xhosa at all? Perhaps it is again about exposure. By including linguistic plurality in the play, Farber forces the audience to rely on the interpretation of the Translator (unless they are fluent in Xhosa, of course). We need to trust in the Translator to give us the correct story. This dependent relationship seems to speak to our willingness to so quickly accept a singular master narrative of history or of historical events. Farber is using two languages and three perspectives (Greek, English contemporary and Xhosa contemporary) to tell the story in Molora. And we, as audience members, are witnessing these three perspectives simultaneously. The use of Xhosa is more than just a mechanism linguistic understanding. It is exposing our lack of understanding, the gaps in our knowledge.

On her site, Yael Farber writes about Molora:

Our story begins with a handful of cremated remains that Orestes delivers to his mother’s door. From the ruins of Hiroshima, Baghdad, Palestine, Northern Ireland, Rwanda, Bosnia, the concentration camps of Europe and modern-day Manhattan – to the remains around the fire after the storytelling is done…

MOLORA [the Sesotho word for ‘ash’] is the truth we must all return to, regardless of what faith, race or clan we hail from. For when fire meets fire, it is only ash that will remain.[6]

Foucault wants the Author as individual to disappear from view into his or her own work. Farber, on the other hand, wants us to appear in our own truth and humanity. Both Foucault and Farber use the idea of ritual – sacrifice for Foucault and fire for Farber – as the means by which we can achieve this disappearance. It is interesting that ash has a double meaning: it is the remains of something that was and also has the potential to spark new life. Farber changes the ending of the original story, saving Klytemnestra and Elektra, breaking the cycle of revenge and robbing the Greek tragedy of its catharsis. By breaking the cycle Farber has exposed the Author, but in doing so she also exposed the Audience and the assumptions we make. If we are all exposed, does that mean we all disappear, or does it mean that we finally look at one another?

When Klytemnestra believes she is to be killed by her son, she says, “Nothing. Nothing is written.”[7]

Perhaps Farber stopped the killing, too. Perhaps her role as Adaptor was to save the Authors and, in turn, save herself.

~A. Bowie, PhD in Humanities Candidate

NOTES

[1] Michel Foucault. Language, Counter-memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews. Edited by Donald F. Bouchard, translated by Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon. New York: Cornell University Press, 1997. 117.

[2] Yael Farber. Molora. London: Oberon Books, 1999.

[3] Ibid, 19.

[4] Michel Foucault. The Archeology of Knowledge and The Discourse on Language. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972. 191-192. The concept is also discussed in one of the class readings – Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology: Volume 2 by Michel Foucault pages 298-301.

[5] Farber, 20.

[6] http://www.yfarber.com/molora/

[7] Farber, 82.

Featured image taken from www.yfarber.com/molora.

WORKS CITED

Farber, Yael. Molora. London: Oberon Books, 1999.

Foucault, Michel. The Archeology of Knowledge and The Discourse on Language. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972.

Foucault, Michel. Language, Counter-memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews. Edited by Donald F. Bouchard, translated by Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon. New York: Cornell University Press, 1997.

Foucault, Michel. Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology: Volume 2. Edited by James D. Faubion. Translated by Robert Hurley and others. New York: The New Press, 1998.