Why doesn’t the Dalai Lama have an H-index?

This probe will investigate citation practices and contemplative knowledge through the framework of discourse as defined by Michel Foucault in On the Archaeology of the Sciences: Response to the Epistemology Circle.

Tenzin Gyatso is the fourteenth Dalai Lama and was recognized as the reincarnation of the thirteenth Dalai Lama at the age of two. The Dalai Lama is the spiritual leader of Tibet and is believed to be an enlightened Bodhisattva who has “postponed their own nirvana and chosen to take rebirth in order to serve humanity” (www.dalailama.com). Born in 1935, his monastic studies began at the age of six and by the age of twenty-three he passed his final examinations which earned him the equivalent of a doctorate in Buddhist philosophy. In addition to his work as the political and spiritual leader of Tibet he has received several honorary doctorates and published over a hundred books. Since the 1980s the Dalai Lama has collaborated with scientists and researchers in a variety of disciplines which has led to Buddhist philosophy informing modern scientific research and conversely modern science has been incorporated into the monastic curriculum at traditional Tibetan institutions.

The H-index is a bibliometric tool used to indicate the productivity and impact of a researcher according to journal publications and citations. Named after Jorge E. Hirsch the H-index is commonly referenced in the valuation or ranking of scientists and scholars. A Google Scholar search on the Dalai Lama returns several results including his 1998 book The art of happiness: A handbook for living which has 413 citations. The top citation of this work is by Richard Layard, Professor Emeritus of the London School of Economics. His 2011 book entitled Happiness: Lessons from a new science is cited 4077 times. Apart from the irony of citing some of the oldest wisdom traditions in the context of a ‘new science,’ the citation system works well for Dr. Layard who has a respectable H-index of 69. Also telling is that ten times more authors cite a respected academic rather than a spiritual leader who has dedicated his life to the study of the subject. Why do we need “sophisticated, cutting-edge, scientific research” (Layard abstract) that will share the same conclusions as the knowledge that has survived from ancient texts? Does the practice of citation offer an opportunity to revisit and revalue older philosophies and practices?

Given that the Dalai Lama is widely cited amid everything from academic publications to motivational posters, how should his authority, authorship and knowledge be considered in relation to established methods of recognition within the scientific and academic community? I will examine this question in relation to Michel Foucault’s proposed methods of discourse analysis. This question also lends itself well to working through Foucault’s assertions on authorship and continuity within history since the Dalai Lama cannot easily be considered as an individual but rather as the representative of a cannon of knowledge and experience going back at least to the 14th century.†

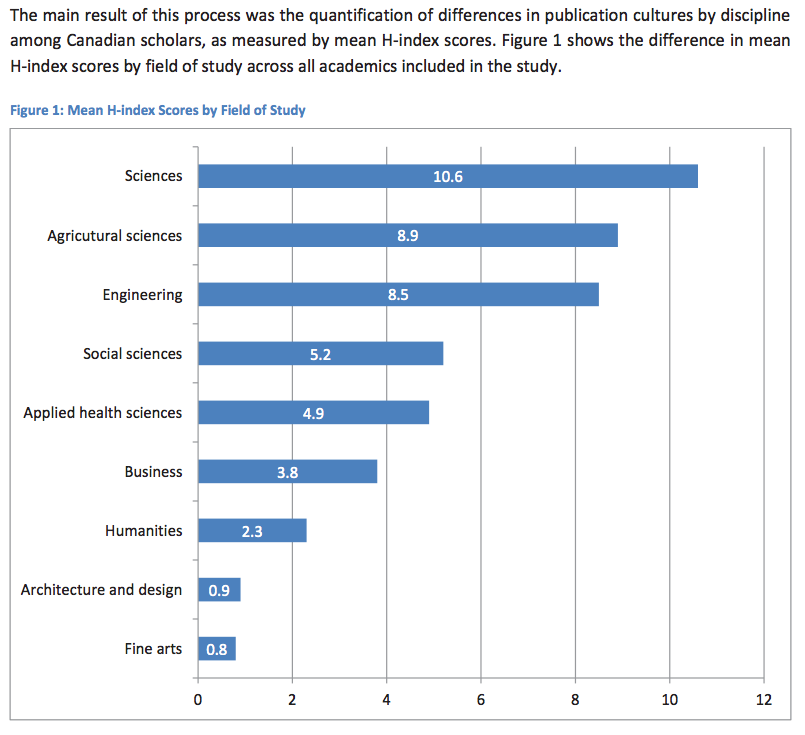

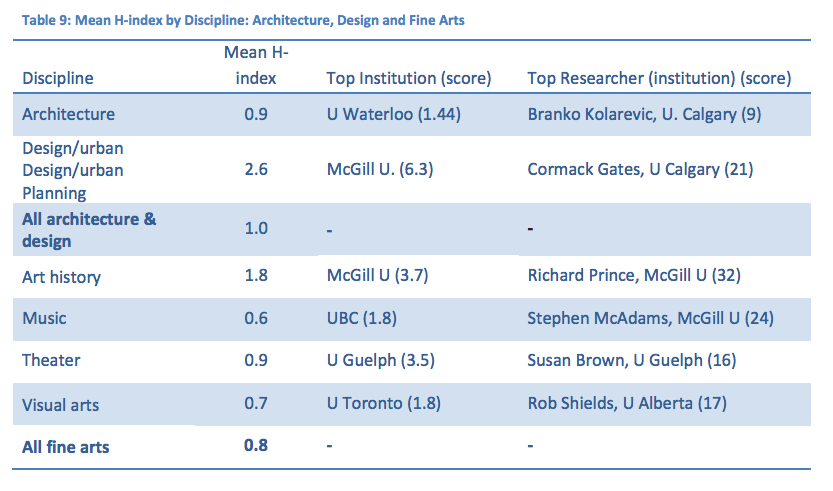

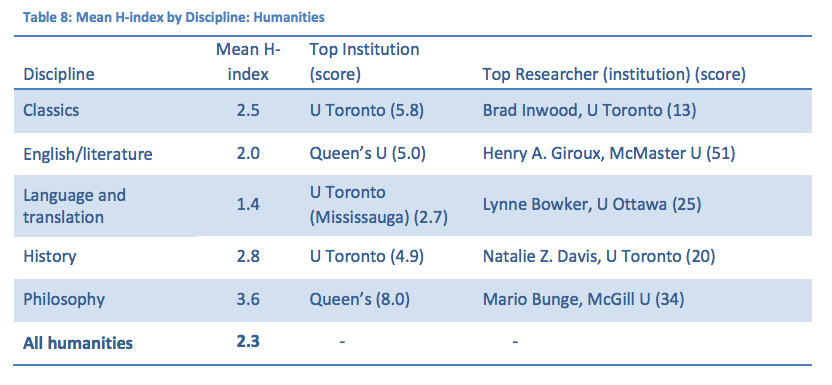

The H-index is considered to work best when applied to scholars within the same discipline since publication practices vary across fields of study. For example, the mean H-index in science is 10.6 compared to 2.3 in the humanities according to a 2012 study by the Higher Education Strategy Associates (HESA) comparing 71 Canadian institutions (Jarvey 15).

A number of criticisms have been raised concerning the methodology of the H-index but regardless it is quickly becoming the most common bibliometric indicator due to the increasing reliance on rankings evident today worldwide. One challenging problem with the H-index is how it favours those who remain strictly within their disciplinary boundaries. Impact is measured by number of citations, a narrow metric which should perhaps be considered as impact within the discipline because it means the most to those also within the field. What is the impact of the Dalai Lama’s work, or of works of fiction? The transcendence of impact in the social and cultural reality of the world make it nonsensical to attempt to give the Dalai Lama an H-index, but it also makes the H-index nonsensical in its own right.

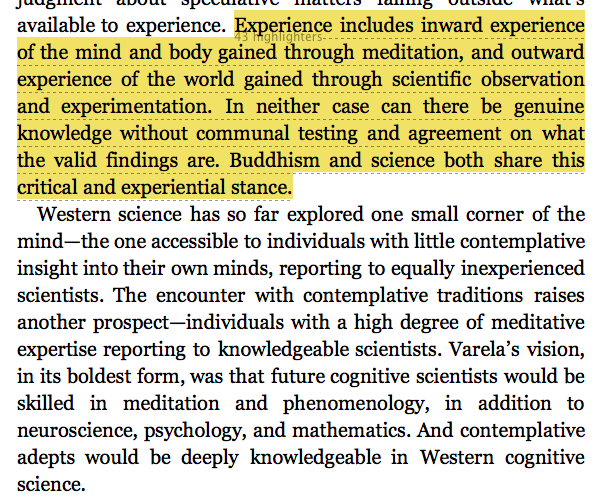

If the validation of knowledge is done by others within the field (as is the case with peer-review) the “referent itself contains the law of the scientific object” (Foucault 331). The way in which knowledge is ascribed value within a field of study could be considered a constitutive part of that field. How should we value knowledge that emerges from a self-justifying system of production and validation? Foucault describes truth as “a system of ordered procedures for the production, regulation, distribution and operation of statements” and is inextricably linked to the systems of power that produce and sustain it (Hacking 35). I see this as the basis for Foucault’s assertion that “the thematic of understanding is tantamount to the denegation of knowledge.” (Foucault 332)

Foucault’s On the Archaeology of the Sciences: Response to the Epistemology Circle provides insight for thinking through these issues. Language is defined as “a system for possible statements” (Foucault 306) and is compared to discourse in relation to the finite or infinite possibilities of statements. Taking simply this description of language, it’s fruitful to consider the value of various works as pursuing the same goal or conveying the same content through different ‘languages’. For example, the Dalai Lama’s and Richard Layard’s books on happiness have similarities in content but are intended to reach different audiences through different means of validation and distribution. If we consider the object in common happiness, then the linguistic definition of happiness offers a limited conception of this entity that doesn’t account for its transformation and translation throughout time. Within Foucault’s discourse, we would instead consider the “law of distribution” through which the referent (happiness) can be understood (313). In this case happiness may refer to something quite different according to context but the unity of the references creates the unity for the referent to maintain some coherence. Ironically when describing the art of happiness, an alternate conception of happiness is precisely what both authors prescribe (to conceive of contentment instead).

In following Foucault’s circuitous logic I feel as though the meaning of a statement is lost early on in the journey. In many ways the path feels analogous to the stochastic Shannon-Weaver theory of information which values the ability to access data (and the probability of that data being found) above all other considerations, such as what the content (meaning) or context may be (Shannon). This theory arose in the context of data being transformed into binary signals regardless of whether the original source was auditory, visual, textual or any other signal that can (in the twentieth century) be translated into the same base code. Foucault’s archaeology highlights the non-disciplinarity of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and his theory of discourse attempts to similarly circumvent disciplinary limits in order to look exclusively at an individual utterance as a unique, autonomous entity. Even though he accepts that the statement is linked to the situation that gives rise to it, he asks that it be considered exclusive of this context. He instead wishes to examine the nature of the statement as “technical, practical, economic, social, political, or other variety” (Foucault 308) which just feels like another kind of classification.

Foucault describes the goal of discourse as attempting to determine why a different statement did not appear in the place of the one given. He wishes for each statement to be evaluated independently to determine why it was chosen in just the way it was. But often there is more than one way to express something, and there can be illogical, inexplicable factors determining what gets said. He is attempting to escape the false continuity that linear, teleological historical narratives generate but the nature of questioning already implies some sort of narrative. If perhaps the only fundamental assertion that can be made is “cogito ergo sum” (I think therefore I am) then a story is already unfolding, namely that I am present and I’ve existed long enough to formulate a question. Narrative is an inherent consequence of consciousness and is built into language even more so. What would the Dalai Lama be without his status as a reincarnated Bodhisattva? Is it even possible to describe Buddhist practices without making reference to the historical construction of the Buddhist philosophy?

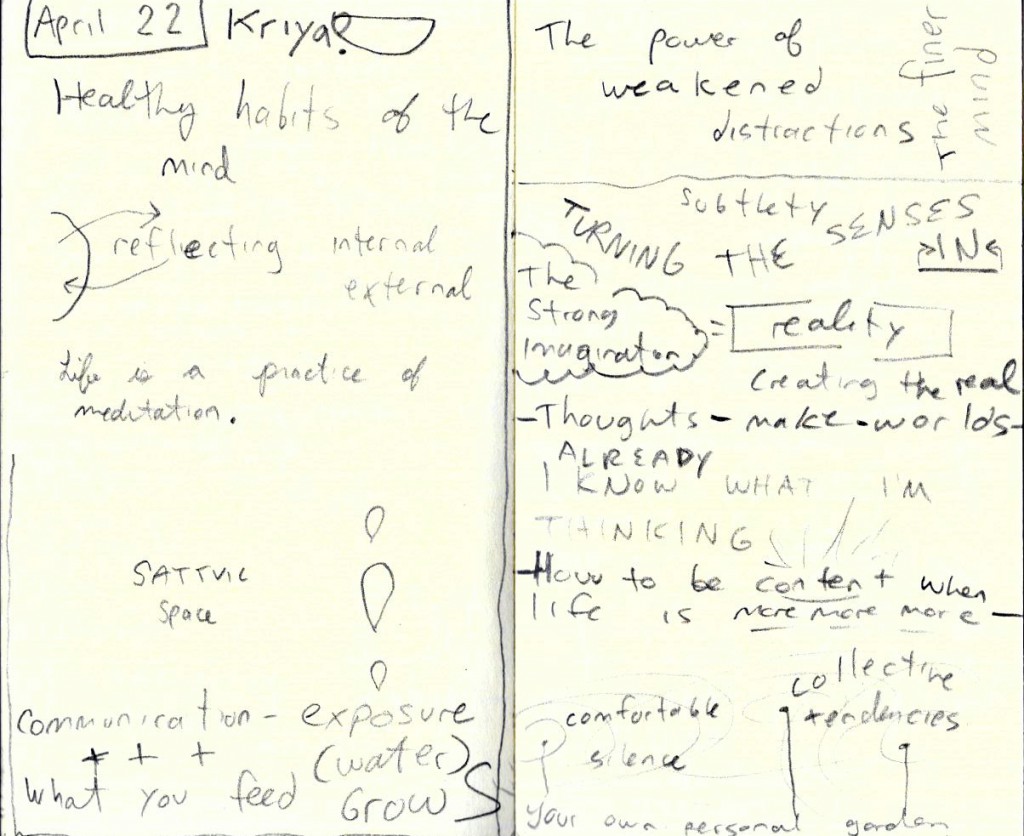

The exercise of trying to grasp and employ Foucault’s discourse analysis can be compared to a passage from Evan Thompson’s 2015 book Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self and Consciousness in Neurosience, Meditation, and Philosophy††. In Chapter 5, which describes neuroscientific sleep studies being conducted with lucid dreamers, he explains how an account of a dream is always given from outside of the dream (Thompson 164). From the moment of awakening there are already linguistic, temporal and cognitive laws shaping the conscious state from which the dream can be recalled and shared. Although Foucault exhausts a plethora of devices and algorithms for examining statements “a statement is always an event that neither language nor meaning can completely exhaust” (Foucault 308). Given this difficulty, perhaps there should be more room for what Foucault considers the problematic origin and narrative tradition he heartily wishes to discard. In one of his most poetic passages about ‘the nonsaid’ he describes discourse as putting into words that which is “already found articulated in the half silence which precedes it” which is then uncovered and rendered silent by its articulation (Foucault 306). This statement reminds me of a note I recorded at a satsang (meditation class) not long ago which was “you already know what you’re thinking”.

Personal page of reflections from April 22, 2015 Satsang at Sattva School of Yoga, Edmonton, Alberta.

This idea was prompted by the discussion about the non-silence that runs through the mind and must be set aside in meditative practice. This ‘narrative on auto-pilot’ can be exhausting if un-checked. The concept that it can reasonably be set aside because it is in fact a circular narrative telling me things I already know liberates me from the stories I tell myself. In this way meditative philosophy and Foucault have a common goal of escaping narrative habits and tendencies. Additionally many East Asian philosophical traditions including Buddhism teach non-attachment to the emotional values habitually ascribed to events. Hence, rather than seeing all things as positive or negative they should instead be taken with a more equanimous, balanced acceptance. Foucault’s project of removing the direct meaning of utterances sounds very familiar in this context.

I think there is value in finding a way to examine ‘enunciative events’ apart from their historical or linguistic ties but it feels counter intuitive to isolate them to the extreme proposed by Foucault. His writing style involves frequently guiding the reader down a path he intends to reveal as fallacious, creating mistrust in the reader that leads to a more critical reading of the text. This strategy could perhaps be employed in his goal of examining discourse. By enacting his philosophy rather than mainly describing it through negation (such as the request to reject traditional models of understanding) readers may follow his path and find themselves no longer needing to cling to traditional modes of understanding. For now I’ll hold onto the aspects of Foucault’s discourse that resonate true within my own systems of valuation, the statements in which he reaches for something beyond what can be described — the “voice as silent as a breath” (305-306).

Works Cited

Foucault, Michel. Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology. New York: The New Press. 1998. Print.

Hacking, Ian. Foucault: A Critical Reader. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. 1986. Print.

Jarvey, Paul, Alex Usher and Lori McElroy. Making Research Count: Analyzing Canadian Academic Publishing Cultures. Toronto: Higher Education Strategy Associates. 2012. Web. Link

Lama, Dalai. The Art of Happiness: A Handbook for Living. New York: Penguin. 2009. Print.

Layard, Richard. Happiness: Lessons from a new science. New York: Penguin, 2005. Print

“The Dalai Lamas.” His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet. The Office of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet. n.d. Web. 26 September 2015. Link

Shannon, Claude. E., and Warren Weaver. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. 1949. Print.

Thompson, Evan. Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self and Consciousness in Neurosience, Meditation, and Philosophy. New York: Columbia University Press. 2015. Print.

† From www.dalailama.com: “In 1447, Gedun Drupa founded the Tashi Lhunpo monastery in Shigatse, one of the biggest monastic Universities of the Gelugpa School. The First Dalai Lama, Gedun Drupa was a great person of immense scholarship, famous for combining study and practice, and wrote more than eight voluminous books on his insight into the Buddha’s teachings and philosophy. In 1474, at the age of eighty-four, he died while in meditation at Tashi Lhunpo monastery.”

†† Thompson does an exemplary job of bridging Eastern and Western philosophical traditions and both are strengthened through his explorations.

Additional images: