Examining a ‘Braingasm:’ ASMR as Cultural Technique

What is ASMR? The neologism is just beginning to creep into contemporary jargon. The first Reddit thread referencing it appeared four years ago and posed this innocuous question — “who else gets this? [head orgasms?]”. For those unfamilar with the ambiguous acronym, it stands for autonomous sensory meridian response, a pleasurable physiological reaction provoked by certain stimuli (common triggers include whispering and tapping, among others). Colloquially, the response is often referred to as “tingles.” While ASMR-related data is highly anecdotal and peer-reviewed research is just beginning to emerge (one article thus far, with more in progress), the community of “ASMRtists” is ever-growing, a bevvy of YouTube moguls whose homemade videos have one goal — to virtually induce this pleasurable, “tingly” brain-bliss in the viewer.

(It’s recommended to watch these videos with headphones to preserve the sound quality.)

One of the most popular ASMRtists, GentleWhispering – this video has over 12 million views.

Within the last few years, ASMR has gained more widespread momentum and the practice of inducing it has emerged as a viable cultural technique. Traditional media has run exposés like this Atlantic article — “How To Have A Brain Orgasm.” Comedian Russell Brand gained ASMR some global notoriety when he examined the phenomenon, asking, “Is ASMR Just Female Porn? ” There is a distinct language which associates its pleasure with sex and therefore a touch of taboo or illicitness, leading to the colloquialism “braingasm.”

Perhaps a more suggestive ASMR video, as it features kissing sounds. Pretty sure it’s still considered SFW, though I’d imagine your coworkers might look at you awkwardly…

Of course, there is a voyeuristic aspect to watching a video designed to make you feel good. I felt both uneasy and fascinated the first time I viewed one. It reminded me of a Kurt Vonnegut short story, “Welcome to the Monkey House,” in which attractive young women soothe volunteers into willing death. Still, as far as I know, no one has died from inducing ASMR thus far, and many of its artists emphasize an association with the world of sci-fi, using outerworldly theming, 3D sound and 360-degree technology in their videos for immersive experiences. For the most part, ASMR techniques are used to ease anxiety or before sleeping, with 98% of users watching “to relax,” 82% “to sleep,” and only 5% “for sexual stimulation” (Barratt & Davis).

A 360-degree ASMR video with a sci-fi narrative

As Siegert notes, cultural techniques “precede the media concepts they generate” (58), ie. the act of writing predates an organized alphabet. Similarly, the term ASMR “was not coined until 2010 and the biology underlying ASMR has probably existed for millennia” (ASMRuniversity.com). Though Seigert points out the reductionism inherent in Macho’s distinctions between “first-order” and “second-order” techniques, ASMR does perform the act of self-reference or thematizing — like this video on how to make an “ear-tickling” ASMR video.

This particular video is also useful in determining the methodologies of the ASMR technique. The process is always enmeshed with technology — binaural microphones, cameras, and computers are vital in order to create a video containing these “triggers.” This kind of interdependence echoes the “‘always already,’ an ontological entanglement of human and non-human” (Siegert 55). And of course, the platform of YouTube plays a fundamental role. One ASMRtist, Claire Tolan, explained in an interview:

“The role of the ASMRtist and the viewer is defined by the allowances of the YouTube interface. There have been some attempts to create ASMR forums outside of YouTube. These exist but they always kind of fade out.”

The algorithms of YouTube constantly adjusting the rankings of ASMR videos (for example, “suggesting” videos to suitable users, or increasing the artist’s search ranking position). The ASMRtists are aware of the algorithm’s role in their success— the most successful ones use titles and descriptions optimized with keywords like “help sleeping”, “de-stress,” etc. They link to other channels, cultivate subscribers and constantly update their content to prove they’re active. YouTube, conversely, is dependent on both these video creators and their audiences to continue data input — they work in symbiosis, a kind of example of the “ontic operations” Siegert names as generators of cultural techniques. And, because the process is dependent on so many non-human components, the technique/technology lines are blurry.

A German media studies scholar, Geoghegan Bernard Dionysius, writes,

“Every cultural technique (Kulturtechnik) tends towards becoming a cultural technology (Kulturtechnik). Where English sharply distinguishes and opposes these meanings, colloquial German designates their intimate and ontologically elusive conjunction” (69).

I liked this quote because sometimes I find it difficult to conceptualize the distinctions between technique/technology, particularly in cases like this when ASMR videos function as both a technology to induce ASMR and yet as a technique, formed of many different variables, in which the technology is only one component.

There’s also the question of the relative “newness” of ASMR and how it could be researched or legitimized in an academic sense. Dr. Tom Stafford of the University of Sheffield posed some doubts about this in this article:

“It might well be a real thing, but it’s inherently difficult to research. The inner experience is the point of a lot of psychological investigation, but when you’ve got something like this that you can’t see or feel, and it doesn’t happen for everyone, it falls into a blind spot. It’s like synaesthesia – for years it was a myth, then in the 1990s people came up with a reliable way of measuring it.”

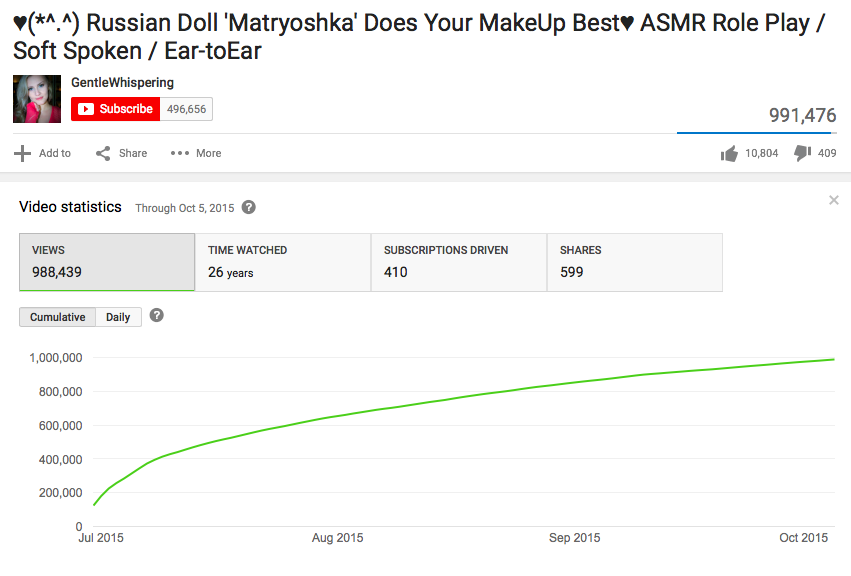

So, how can ASMR be measured for validity’s sake? In an interview regarding media cultures, Jussi Parikka speaks of the “questioned notions of the temporality of media culture; instead of a linear, progressive time of media, does it follow cycles or other modes of repetition?” In consideration of Parikka’s question, we can examine the tendencies towards emerging research in ASMR via analytical data. Certainly, some aspects of web analytics appear stripped of temporality (ie. number of subscribers or shares as a measurement of how many people engage with it) but a lot of it is still dependent on a traditional linear narrative, as you can see in the screenshot below. There’s also a variance in how effectiveness can be measured — for example, a human perspective may privilege the physiological reaction provoked from watching, but the inner workings of the YouTube platform would determine ASMR’s “success” very differently in terms of the number of users it drives within the platform, the number of video uploads it receives, etc. Is there a definitive measure of its effectiveness?

Do these statistics mean that ASMR is “real?”

Krämer and Bredekamp make an analogy of calculus which can extend similarly to ASMR practice; they note that the “aesthetic produces and constitutes these kind of ‘objects’ at the moment of their visualization in the first place” — a technique “feeding” a concept into the register of sensory perception (26). In this sense, the ASMR video can be an object/actor which serves as a focal introductory point to enlightening the body’s physiological capabilities for this, while promoting ongoing growth of a lexicon to accompany the technique.

I found Bourdieu’s comments on the body to be useful in analysis of ASMR as well. Bourdieu’s theories of habitus account that “our ways of ‘being in our bodies’ are also socially conditioned” (Sterne 376), with “a certain kind of physicality and social memory to it” (381). The ASMRtists of YouTube appear very similar — at least, the ones with the most subscribers do. I can’t see any published research on it, but scrolling through the YouTube archives, there appears to be one common ASMRtist archetype. ASMRtist Claire Tolan elaborates:

“In terms of gender roles: the videos are often made by young women . . . the role of the caregiver is so often a feminine role . . . this too-perfect care is not often done but it can be done. Care that is not tethered to any reality . . . “

In terms of social conditioning of the body, the feminine-caretaker trope is a tired one, but it raises the question: what bodies are we conditioned to respond to as “soothing” or “relaxing?” The top-subscribed ASMRtists aren’t a great representation of racial diversity, either, as discussed in this Reddit thread. In this offshoot of YouTube, something so niche and particular, it appears larger social problem-patterns are still influential. Though artists outside this archetype exist, they didn’t surface for me until I kept scrolling for a bit, and they don’t have as many subscribers overall.

Other questions I developed throughout this probe were:

- What other ontic operations played a role in the development of ASMR as technique?

- How can the connotations of “weirdness” re: these videos be examined? Is it connected to a kind of posthuman angst, or is it the very humanity of the central ASMRtists that causes some to feel uncomfortable?

- How will the technique change as its technology changes? If ASMR videos utilized a non-human-generated voice and face, would they gain as many fans? (Until Siri sounds a little less monotone, I’d have to guess not.)

Works Cited

[header image credit: PotLuckBrigand/ Deviantart.com]

ASMRUniversity. “The History of ASMR.” asmruniversity.com. ASMR University, 2014. Web. 11 Oct 2015.

Barratt, Emma L. & Nick J. Davis. “Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR): A flow-like mental state.” PeerJ 3:e851 (2015). Web. 11 Oct 2015.

Beck, Julie. “How to Have a ‘Brain Orgasm.'” theatlantic.com. The Atlantic Monthly Group, 16 Dec 2013. Web. 11 Oct 2015.

Brand, Russell. “Is ASMR Just Female Porn?” russellbrand.com. The Trews Ep. 298, 14 April 2015. Web. 11 Oct 2015.

Bredekamp, Horst & Sybille Krämer. “Culture, Technology, Cultural Techniques – Moving Beyond Text.” Theory, Culture & Society 30.2 (2013): 20-29. Web. 16 Oct 2013.

Geoghegan, Bernard Dionysius. “After Kittler: On the Cultural Techniques of Recent German Media Theory.” Theory, Culture and Society 30.6 (2013): 66-82. Web. 11 Oct 2015.

Hugill, Alison. “An Interview with the ASMRtist: Claire Tolan.” berlinartlink.com. Berlin Art Link Productions, 14 July 2015. Web. 11 Oct 2015.

Marsden, Rhodri. “‘Maria spends 20 minutes folding towels:’ Why millions are mesmerized by ASMR videos.” independent.co.uk, 21 July 2012. Web. 11 Oct 2015.

Parikka, Jussi & Garnet Hertz. “CTheory Interview: Archeologies of Media Art.” Resetting Theory 20.0 (2010). Web. 11 Oct 2015.

Siegert, Bernhard. “Cultural Techniques: Or the End of the Intellectual Postwar Era in German Media Theory.” Theory, Culture & Society 30.6 (2013): 48-65. Web.

Sterne, Jonathan. “Bourdieu, Technique and Technology.” Cultural Studies 17.3/4 (2003): 367-389. Web.