“There’s no good way to know for certain if I’m not lying. Or something.”

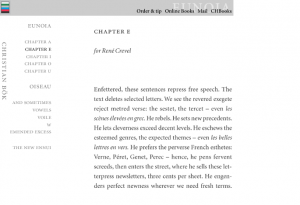

Conceptual Poetry is a mode of contemporary writing best explained to the uninitiated through a close reading of its title: Poems or pieces of “text” are constructed and constrained by and through a centralising conceptual idea. Conceptual Poets take ideas, imaginings, and thoughts and then enact them—either in extremely literal ways or in extremely abstract ways. There is rarely a middle-ground in capital C “Conceptual” works. The unifying factor is the constraint of content and a strict adherence to a set structural pattern. The most straightforward example is probably Christian Bök’s 2001 novel Eunoia, which features five chapters each limited to words with just one vowel.

“Chapter E” of Christian Bok’s Eunoia (source)

Conceptual work is not teleological, or often even representational, but rather focusses on the original and binding concept. This often leads to a privileging of structure over content, as well as appropriative use of older pieces in the process of forming new ones:

In conceptual poetry, appropriation is often used as a means to create new work, focused more on the initial concept rather than the final product of the poem. In its extreme form, such works are process-oriented and nonexpressive. Some of these works include large amounts of information and are not intended to be read in their entirety. (Poets.org)

Conceptualism has been popularised by American poets Vanessa Place and Kenneth Goldsmith, both of whom have recently been criticised for their appropriative usage of African-American culture. In a performance-art piece entitled “The Body of Michael Brown,” Goldsmith read the autopsy report of unarmed murdered black teenager Michael Brown at an event at Brown University, altering the text in order to “narrativize” it (De Jesus). While Goldsmith’s explanation of the piece justified the act as a “powerful” comment on the injustice of systematic racialized oppression, his use of the medical document and manipulation of it into a narrativized poem is problematic, especially considering his response focusses more on the merits of Conceptualism as a form and his practice of it than on systematic and racialized police violence in America. Vanessa Place has also been criticised for her Conceptual work (usually considered radically feminist) after a four-year project on Twitter during which she tweeted lines from Gone With the Wind with an image of Hattie McDaniel playing Mammy as her avatar.

While the work of Goldsmith and Place is particularly dangerous for its lack of acknowledgment of privilege and appropriation, it draws on a trend in Conceptual work that posits that the conceptual always trumps the material or the bodily subject. Place’s piece is conceptually designed to ignite a lawsuit with Gone With the Wind’s publisher that would force the corporation to acknowledge the novel’s perpetuation of racism. However, Place’s mode of igniting the issue has been called racist and insensitive, especially since her tweets can be taken out of context on the extremely public interface. Likewise, Goldsmith’s conceptual move of reading autopsy ~*~as performance~*~ privileges his freedom as an artist to make the social issue a conceptual art piece. In both cases, the ideal of the work as work overshadows the political and radical intentions of the poets. They dig their heels in instead of apologising or re-assessing. Conceptualism’s denial of the corporal, tangible, and very real body is inextricably linked to being in the privileged position of being able to forget the body. This becomes an issue when Conceptual works engage with issues that emerge from radically different social contexts—ones where the body is inherently inseparable from the way it look and therefore from how is treated.

While the engagement of Conceptual poets with social issues is often precarious, the very construction of the mode’s form and conventions can also be implicitly exclusionary. The idealisation of form and structure over content, and the privileging of discipline and restraint, speaks to disengagement with the personal, the individual, or the “messy” emotive sphere. “Pure” Conceptualism is ideally unreadable, or pointless to actually read, which heightens that division. As in many canonical and didactic views on poetry, using the lyric “I” voice, or engaging with the “self” seems to be discouraged, or, at the very least, not valued as highly as a removal from the personal sphere. Excess, lack of control, and interest in the self are often associated with female poetics, especially with work deemed “confessional.” It is no secret that such work is often regarded with contempt in both the academy and pop culture, especially in the case of women writers.

Confessionality is often seen as synonymous with the style of teenage diaries (or at least with popular imaginings of teenage diaries, because honestly, who’s actually reading the personal diaries of teenagers?!?!), and is therefore seen as a trite and immature expression of excessive emotional overflow. Judgements about this style of writing are inordinately gendered towards young female writers, as teenage girls are culturally linked to emotional excess, romantic obsession, hysteria, and narcissism. Autobiographical work by women is almost always seen as inherently narcissistic, excessive, and messy, while male autobiographies (usually billed as memoirs, and rarely as confessional) are reminders of the unified male self, and any sign of instability is a brave expression of vulnerability.

How do these views about “confessional” work relate to Conceptual Poetry, Media Theory, and New Materialism?

Material excess and bodily materiality—both are often figured as inherently Bad, embarrassing, or lazy. In terms of capitalist consumption and ecological waste, as well as consumer culture: yes, they are BAD. Most can probably agree on the wastefulness of North American consumption. In her theory on body materialism, Jane Bennet focusses on “thing-power,” a theory that posits that stuff, or our material surroundings “command attention as vital and alive in its own right, as an existant in excess of its reference to human flaws or projects. […] it commands attention, exudes a kind of dignity, provokes poetry, or inspires fear ” (Bennett 350). Bennett argues that excess devalues thing-power; it obscures the “specialness” of each object and its influence. Criticism of material excess and over-consumption are often inherently gendered, much as they are in discussions around lyric and Conceptual poetry. Moreover, much of academic theoretical discourse either cloaks or ignores the body, and how bodies operate differently in different contexts. While Bennett’s work places value on thing-power as a potentially radically approach to theorizing ecological matter, her views on excess draw on gendered notions of female relationships to objects.

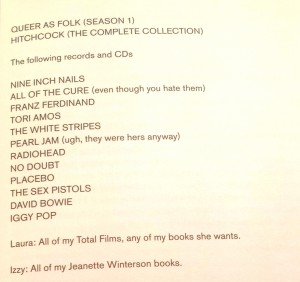

In her 2013 conceptual novel The Compleat Purge, poet and public critic Trisha Low explores popular conceptions of confessionality and teenage culture through a constrained conceptual text in the mode of Lyric Conceptualism (a mode of Conceptual Poetry solidified by Sina Queyras in her “Lyric Conceptualism, A Manifesto In Progress”, which calls for inclusion of the bodily, the self, and the “I” in conceptual work). Low’s novel opens with a cycle of suicide notes written by various iterations of a “Trisha Low,” followed by a parodic ladies’ conduct novel detailing the assault of a “Trisha Low”; chat-room fantasies written by an online “Trisha Low” featuring members of The Strokes and Dirty Pretty Things; and a closing academic dissertation by “Trisha Low” on the notion of authenticity and the conceptual mode. Throughout the novel, various iterations of “Low” list their material possessions. Low’s fixation on materiality speaks to cultural views on how teenage girls relate to their possessions: passionately, fixedly, and in excess.

How does Bennett’s notion of thing-power apply to these instances of possession that are marked as overly excessive or emotional?

Low’s answer is to meet the reader’s eyes while winking very slowly, telling us that she knows what the autobiographical and “confessional” expectations are for her work as a millennial, POC women writer. Low knows what we think, and she doesn’t give a shit whether she lives up to our expectations (disappointments) or not.

Trisha Low reading “Hunting Season,” 2014

Low always reminds me of what the critic and scholar Terry Castle wrote in her NY Review of Books piece on Sylvia Plath in 2013. I’ll never forget it. Castle said that Plath is a “sensation still among bulimic female undergraduates.” Low both confirms and denies that you know what she’s about to do. She plays with our faith. She makes us believe that it is okay to cry about how your hair looks and then go do a seminar presentation on actor network theory. That there is no shame in being a young women who wants to write poems and then isn’t shy about how good they are in seminar. She’ll make us have faith, in these things that we already know to be true, but that we doubt sometimes. And she’ll do so through a sixty page transcript of fanfic chatroom cybersex, written from the perspective of a fifteen year old girl pretending to be Julian Casablanacas’ girlfriend.

vocal fry / excess / hysteria / selfies / too many selfies / loss of control of emotions due to onset of menstruation – is the valuing of abstraction, disassociation, and disembodiment linked to gendered ideas about intellectualism, knowledge, and theory within the academy, or am I just being like, so dramatic?

A recurring thread this term has been accessibility—who is actually going to read these theories, and how will they be understood? Two weeks ago Chalsley asked who gets to count as an “academic/intellectual.” I’m wondering much of the same. When modes of poetic discourse that rely on seemingly “confessional” or personal voices are dismissed, when capital T theory often upholds a privileging of conceptualisation over materiality—what are we conveying about the hidden values of these modes? Often, it seems as if the modes of expression generally associated with women are those that are questioned or devalued. Often, it seems as if daring to speak about the body, the self, or the personal is inherently less valuable than abstraction, conceptualism, or objectivity.

Is this a problem unique to a small subset of contemporary poetry that I happen to care about a lot? Noooooooooooo. The ways in which gendered judgments about writing and expression operate in public circulation of poetics is inextricably tied to how women’s voices are received publically. The mistrust and devaluing of women’s voice is pervasive, and highly visible. What does this look like outside of text, outside of theory, and outside of poetry?

It looks like longstanding inequity in Canadian publishing.

It looks like public figures saying that young women in academia are foolishly investing in “faddish social justice issues” and “sexism narratives, cause politics and “identity” zealotry.” It looks like critical, careful, measured, and vital responses to these issues being taken up by “satirical” “humour” magazines and mocked.

It looks like my expression after a student in the course I TA asks me how old I am with a huge smile on his face. A bigger smile when I feel compelled, despite myself, to answer in a polite manner (no source available).

It looks like the time my undergraduate professor invited me to help move his apartment and fed me scotch and beer while the CBC radio signal frizzled (no source available).

It looks like the feedback I got on a seminar presentation (which received an A+) that said “your voice tends to go up at the end of sentences, you might try to change that” (no source available).

It looks like some of our tutorial seminars on a bad day, or even on a good day, when there is no room to speak or contribute—not because our peers are inherently vindictive, but because we haven’t always been taught to think of ourselves as deserving to speak first, last, or often (no source available).

It looks like the ways in which we listen to, believe, disbelieve, and respond to young women have serious and tangible effects on our quotidian existence. Or like, whatever (no source available).

Works Cited

“A Brief Guide to Conceptual Poetry.” Poets.org. Academy of American Poets, 2014. Web. 13 Apr. 2015.<http://www.poets.org/poetsorg/text/brief-guide-conceptual-poetry>.

Bennett, Jane. “The Force of Things: Steps toward an Ecology of Matter.” Political Theory 32.3 (2004): 347-72. Print.

Castle, Terry. “The Unbearable.” The New York Review of Books. NY Books. 11 July 2013. Web. 24 March 2014.<http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2013/jul/11/sylvia-plath-the-unbearable/>.

De Jesus, Joey. “Goldsmith, Conceptualism & the Half-baked Rationalization of White Idiocy.” Apogee. Mar. 18. 2015. Web. 14 Apr. 2015. http://www.apogeejournal.org/goldsmith-conceptualism-the-half-baked-rationalization-of-white-idiocy/.

Murphy, Rex. “Institutes of Lower Education.” National Post. 27 Sept. 2015. Web. 17 Oct. 2015. <http://news.nationalpost.com/full-comment/rex-murphy-institutes-of-lower-education>.

Works Consulted

“2014 CWILA Count Infographic.” CWILA Canadian Women In The Literary Arts. 07 Oct. 2015. Web. 17 Oct. 2015. <http://cwila.com/2014-cwila-count-infographic/>.

Ahmed, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. New York: Routledge, 2004. Print.

Berlant, Lauren. The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture. London: Duke UP, 2008. Print.

Bertram, Lillian-Yvonne. “The Whitest Boy Alive: Witnessing Kenneth Goldsmith.” Poetry Foundation. 2015. Web. 17 Oct. 2015. <http://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet/2015/05/the-whitest-boy-alive-witnessing-kenneth-goldsmith/>.

Bök, Christian. “Eunoia, Chapter E.” Eunoia, Christian Bök. Web. 17 Oct. 2015. <http://archives.chbooks.com/online_books/eunoia/e.html>.

Bök, Christian. Eunoia. Toronto: Coach House, 2001. Print.

Crocker, Lizzie. “Does Tweeting ‘Gone With the Wind’ Make This Poet Racist?” The Daily Beast. Newsweek, 28 May 2015. Web. 17 Oct. 2015. <http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/05/28/does-tweeting-gone-with-the-wind-make-this-poet-racist.html>.

Douglas, Andrew. “Wunker of the Week.” Frank Magazine. 29 Sept. 2015. Web. 17 Oct. 2015. <http://www.donotlink.com/www.frankmagazine.ca/node/4272>.

Fassler, Joe. “How Doctors Take Women’s Pain Less Seriously.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, 15 Oct. 2015. Web. 17 Oct. 2015. <http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/10/emergency-room-wait-times-sexism/410515/>.

Gill, Jo, Ed. Modern Confessional Writing: New Critical Essays. London: Routledge, 2006. 1-10. Print.

Healey, Emma. “Stories Like Passwords.” The Hairpin. 06 Oct. 2014. Web. 17 Oct. 2015. <http://thehairpin.com/2014/10/stories-like-passwords/>.

Johnson, Jim. “Mixing Humans and Nonhumans Together: The Sociology of a Door-Closer.” Social Problems 35.3 (1988): 298-310. Print.

Junaid, Jia. “I Didn’t Believe the Women Accusing Jian Ghomeshi, and I’m Ashamed.” The Star. 2 Nov. 2014. Web. 17 Oct. 2015. <http://www.thestar.com/opinion/commentary/2014/11/02/i_didnt_believe_the_women_accusing_jian_ghomeshi_and_im_ashamed.html>.

King, Amy. “WHY ARE PEOPLE SO INVESTED IN KENNETH GOLDSMITH? OR, IS COLONIALIST POETRY EASY?” VIDA: Women in Literary Arts. 18 Mar. 2015. Web. 17 Oct. 2015. <http://www.vidaweb.org/why-are-people-so-invested-in-kenneth-goldsmith-or-is-colonialist-poetry-easy/>.

Low, Trisha. “An Interview with Trisha Low.” Interview by Coco Papy. Bookslut. Dec. 2013. Web. 12 Mar. 2014. <http://www.bookslut.com/features/2013_12_020428.php>.

Low, Trisha. “Portrait of the Marquis De Sade as a Young Female Hacker.” Interview by Blake Butler. VICE. 21 Nov. 2014. Web. 12 Mar. 2014. <http://www.vice.com/en_ca/read/portrait-of-the marquis-de-sade-as-a-young-female-hacker>.

Low, Trisha. “Trisha Low Reads “Hunting Season,” February 6, 2014.”YouTube. PennSound, 13 Feb. 2014. Web. 17 Oct. 2015. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XVScqtph-4w>.

Low, Trisha. The Compleat Purge. Berkeley: Kenning Editions, 2013. Print.

Parikka, Jussi. What Is Media Archaeology? Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2012. Print.

Queyras, Sina. “Lyric Conceptualism, A Manifesto In Progress.” Harriet. Poetry Foundation, 9 Apr. 2012. Web. 6 Mar. 2015.

Smith, Rich. “Vanessa Place Is in a Fight Over Gone with the Wind‘s Racism, But It’s Not the Fight She Says She Wants: An Interview.” The Stranger. 21 May 2015. Web. 17 Oct. 2015 <http://www.thestranger.com/blogs/slog/2015/05/21/22251060/vanessa-place-is-in-a-fight-over-gone-with-the-winds-racism-but-its-not-the-fight-she-says-she-wants-an-interview>.

Voigt, Ellen Bryant. The Flexible Lyric. London: Georgia UP, 1999. Print.

Wunker, Erin. “Dear Rex Murphy: Dismissing Rape Culture Crisis on Canadian Campuses as ‘faddish’ Is

Reprehensible.” Rabble. 29 Sept. 2015. Web. 17 Oct. 2015. <http://rabble.ca/blogs/bloggers/campus-notes/2015/09/dear-rex-murphy-dismissing-rape-culture-crisis-on-canadian-campu>.

[…] my last probe I wondered about how we frame the voices of young women, such as poet Trisha Low. An assumption […]