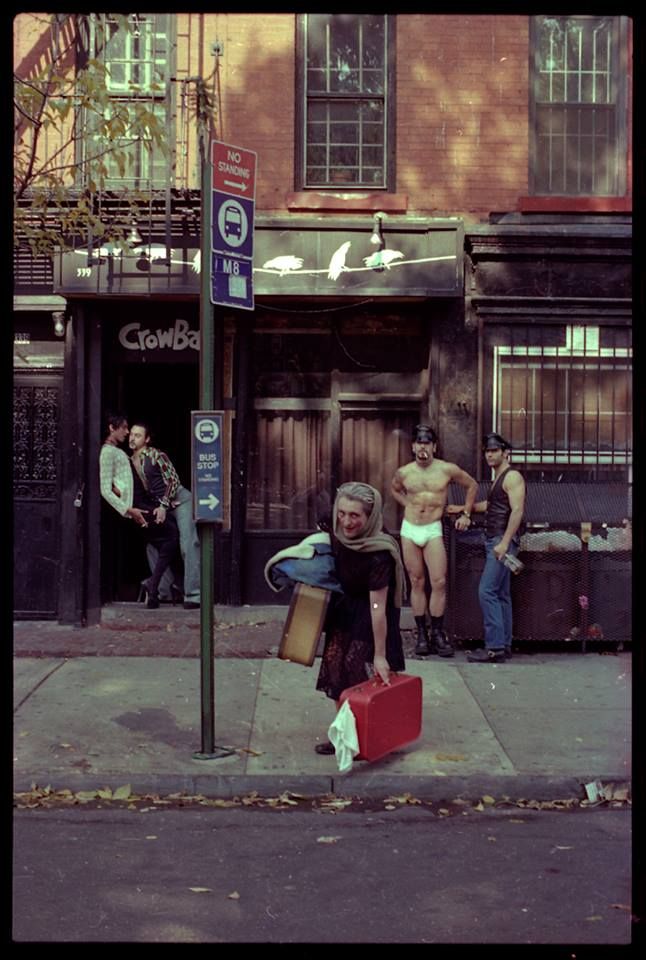

The Media Lab as a Leather Bar

The Village, a Gay Titanic

Michel Foucault’s concept of heterotopia, grounded as it is in our course in the idea of the media lab, made me think of a major concern I have when it comes to my scholarship on city space. Specifically, it made me think of the gay village, and Montreal’s Gay Village in particular, as a kind of utopia, or heterotopia. In her book on Walter Benjamin and The Arcades Project, The Dialectics of Seeing, Susan Buck-Morss writes about the arcade as reflective of bourgeois utopian dreams through its references to commodity fetishism, prostitution, gambling, etc. The gay village is built on a similar kind of utopian idea of safety, freedom, and a particular kind of aesthetics.

Yet, Montreal’s Gay Village is failing. While centrally located and a tourist attraction, especially in the summer, businesses are closing all along Saint Catherine Street, bars are losing their younger patrons and the area is generally seen as less desirable to live in due to violence, homelessness and the economic median. The Village, with its aggressive (yet dwindling) consumerism that certainly defines it as both “gay” and a “village” (bathhouses, sex shops, leather bars, etc.), has become normalized, normativized and boring. Left on the margins of contemporary queer life in the city, I question if the Village might constitute a heterotopia if it fails to be contradictory or disruptive, to be the “other” space that excludes normality while emulating a particular kind of utopia.

Where does the Village fail? In “Of Other Spaces,” Foucault writes of the Middle Ages as a “hierarchic ensemble of places: sacred places and profane places […] It was this complete hierarchy, this opposition, this intersection of places that constituted what could very roughly be called medieval space: the space of emplacement” (22). While I would not go as far as to call the Village Medieval, there is something to be said about the fact that, in the absence of a vibrant activist or community-building impulse, the Village has been reduced to that of a shopper, and for this purpose banks on the idea of the “profane.” After all, porn theaters, bathhouses and leather bars are what today’s gay village is. Where it could have been the topsy-turvy place of the carnivalesque, it is not much more than the place of role-play. It is hardly “hetero,” and no one even bothers with the “utopian” part anymore. Certainly, one could speak of the Mile End as an alternative to the village as a reconfiguration of the antiquated idea of “villages” and “ghettos” in a more diverse dress (men, women and others; straights and queers alike), and a space that is queer/heterotopic by default. Otherwise, the dying gay institutions such as the bathhouse, or the YMCA, may betray a sense of heterotopia as deviation and ritual. If we pushed it, today’s village might be heterotopic in a similar way to a cemetery, not only in that it is a dying place, but also in the tradition of gayness as a death of sorts: in her book AIDS Literature and Gay Identity: The Literature of Loss, Monica B. Pearl posited that AIDS was not the first time that “loss, mourning or death” demarcated the gay population, but that it is a part of a larger tradition of interplay between gayness and death, either biological or that of innocence, of the heterosexual identity, of parental/adult authority, or of the natural order” (Pearl 8). Yet, in spite of this macabre, and mythical understanding of the Village, I am still not certain if the Village is the Foucauldian boat for Montreal queers.

The Street Between Four Walls

What of media labs, though? What kind of work can be done in them, especially in terms of urban studies? This is the kind of question that was buzzing around my mind as I thought about the Village as this fixed, inoffensive slice of urban landscape, and I couldn’t help but wonder if the media lab just might be the solution. When, at a round table on media labs, Prof. Darren Wershler spoke of the media lab as heterotopia, both material and imaginary, institutional (relating to, and being funded by a university, for example) and deviant (contained, removed from more traditional modes of knowledge production) (“What Is a Media Lab?”), I kept thinking back of the Village as a mythical project and a much more concretized reality. Would a media lab problematize, or transform, the Village in ways that the Village itself cannot? What would it mean to study the Village at such a distance – both physical and methodological?

If one were to create a media lab based on the study of space, what kind of objects would it contain? Maps, leaflets, flyers, advertisements, street signs, blueprints, coasters with logos of bars underneath… Yet, what would this all do? I am wary of the idea of the database, or the archive – they not only seem so antiquated, but they also seem limited and insular. A media lab, as a think tank, a heterotopia of ideas, objects, and circumstance would have to (re)arrange these artifacts and take them apart like LEGOs in ways that would disrupt and destabilize a place’s accumulated normalcy.

These objects would constitute different media, instances of different mediation of the city space that, in turn, would have agencies of their own. The media lab, then, would constitute a particular assemblage of media and methodology, with an agency unto itself. If, for example, its main three methodologies would fall into the fields of film studies, literature and art history as disciplines that have helped shape our understanding of a particular city space, then a process of curation would not suffice. These material or digital assets would have to then intersect methodologically as well as topically in order for the humanities student to create not a thesis, but an ideology: an overwhelming approach that would valorize certain objects over others, and to, as Jentery Sayers puts it, “yack about theory and process” (“The MLab: An Infrastructural Disposition”). In a decidedly alternative, more informal research space, the media lab’s job would ultimately be to create a kind of vernacular of talking about space (the Village, in this case), which for me constitutes the poetic crux of the thing: coming up with a different vernacular to talk about things that are vernacular to begin with – the city streets, desire and the quotidian. It is heterotopic to the max.

My two questions are as follows: How would one bring the study of space, and in particular urban spaces, into a media lab, especially considering observation and location-specificity of places as a traditional way of studying them? Would we resist the idea of curation of objects, or sorting them into databases, or would the media lab resolve the fixity of such an approach through some other methodologies? It is a similar question, I think, to Sayers’, when he asks, “What makes tactical media persuasive?” (“The MLab”) Furthermore, does a media lab have a shelf life of a gay village? Is it ever in peril of being fixed, or institutionally normalized, both in terms of its thesis and its methodology?

If a media lab ceases to be an “other place,” does it simply become a leather bar?

Notes

Buck-Morss, Susan. The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1989. Print.

Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces.” Trans. Jay Miskowiec. Diacritics 16.1 (1986): 22-27. JSTOR. Web. 10 Oct. 2014.

Pearl, Monica B. AIDS Literature and Gay Identity: The Literature of Loss. New York: Routledge, 2013. Print.

Sayers, Jentery. “The MLab: An Infrastructural Disposition.” Maker Lab in the Humanities. University of Victoria, 29 June 2015. Web. 05 Nov. 2015.