WELCOME to the Techno-Dystopian Future!

In this probe I will examine the enchanting and problematic trope of thinking about the future as an abstract, fictional and perpetually deferred time. I will describe the present in relation to techno-utopian ideas of the past and attempt to map out what a humanities-based media lab can enable for researchers concerned about utopian representations of the technological.

Yesterday’s Future

Much speculation about the future of humans and machines is born in the world of science-fiction. Unfortunately this creative genre of literature often relies on certain themes and stock scenarios that easily ignore logistical aspects such as energy (Ghosh, 1992). Since the nineteenth century, celebratory expos and world’s fairs have taken imaginative futuristic concepts and put them on display alongside exotic imported cultural expositions from around the world. Art works were also displayed as samplings from human cultural history to complete the narratives and frame the technologies of the future.

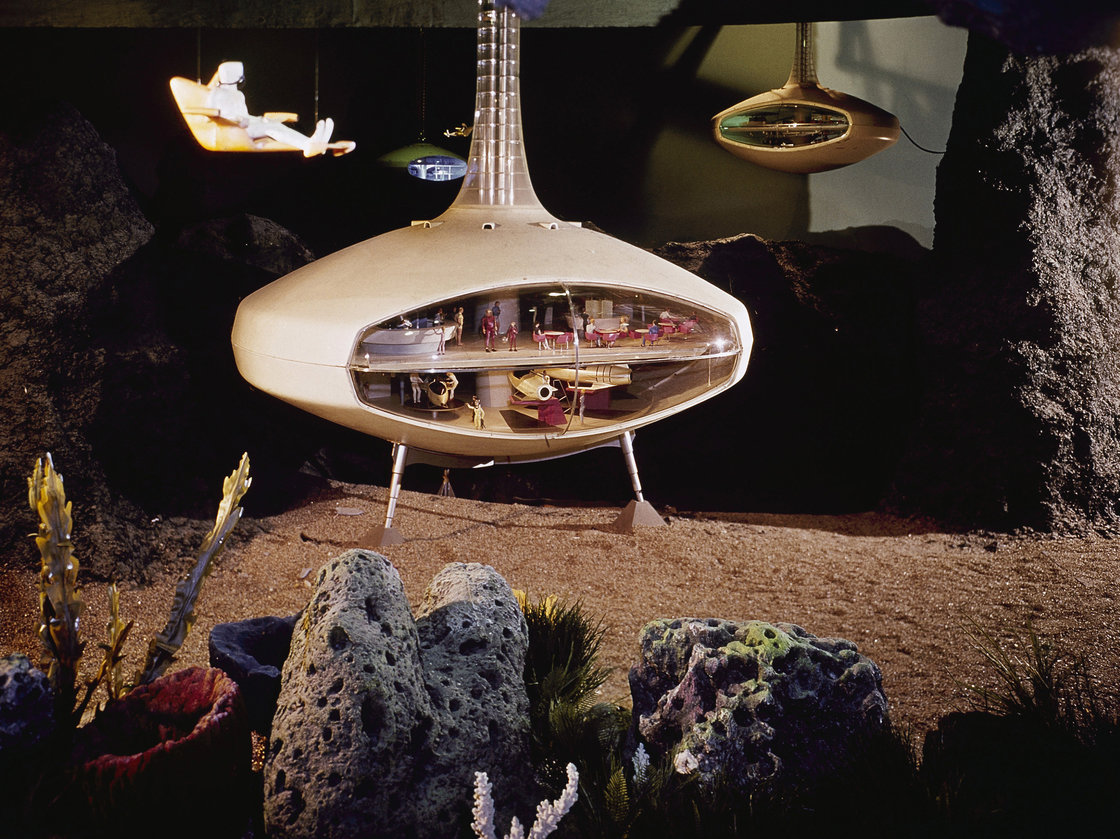

A brief overview of the technologies of the future presented at the 1964 New York World’s Fair include picture phones, hotels under the sea, and giant machines that would cut through jungles to build roads bringing “the goods and materials of progress and prosperity” to newly productive communities. (Futurama II exposition video 4m15s – 5m00s).

According to this archival video promoting the Futurama II exhibit at the 1964 fair, the technology of the future will “free the mind and the spirit as it improves the well-being of mankind”. This video exemplifies the American-centric, man-over-nature, positivist ethos of the day. I found the promotional video simultaneously quaint and irritating but a more politically correct version of techno-utopian thinking is still quite common today. In their 1997 contribution to the book Beyond Calculation: The Next Fifty Years of Computing, technological determinists and Microsoft employees Gordon Bell and James N. Gray offer the following:

“In 2047 almost all information will be in cyberspace – including a large percentage of knowledge and creative works. All information about physical objects, including humans, buildings, processes and organisations, will be online. This trend is both desirable and inevitable.” (Denning, 5)

Isn’t there a more nuanced, critical and reflexive way of thinking about the future? In what ways have academic researchers been involved in shaping technological innovation?

Stewart Brand’s book The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT proclaims in its title exactly what MIT Media Lab founder Nicholas Negroponte wants people to think goes on in the multi-million dollar laboratory. Through extensive discussions with Negroponte Brand paints a picture of the Media Lab that is closer to advertisement than critical examination. As stated on page 263, one goal of the book was to help the lab consider what its emergent academic discipline might be. The author claims to have failed to accomplish this task. I think Brand’s error may have been to ‘drink the kool-aid’ by buying in to the lab’s exciting promise of “inventing the future”. While the book provides a useful exposé of the projects and infrastructure of MIT’s Media Lab at the turn of the twenty-first century, Robert Hassan effectively summarizes the issues inherent in the lab’s ideology in his article The MIT Media Lab: techno dream factory or alienation as a way of life?

“The informational ecology is unproblematic for corporate capital that underwrites the Media Lab. Indeed, big business views it as vital to the future viability of the so-called ‘new economy’. As they see it, interconnectivity and the new economy go hand in hand, a friction-free and networkable cycle of production, distribution and consumption.” (Hassan, 104)

The Media Lab was poised to cater to the newly merged industries of computing, broadcast and motion picture industries, and print publishing. Negroponte was able to consistently secure millions of dollars for the lab from corporate investors who in return get a glimpse of the “future”. Fantastical conceptualisations of the future and the perpetual deference of crisis to a time where problems magically disappear through innovation is part and parcel of the story of capitalism. This mode of thinking is particularly evident and problematic as economies rely increasingly on credit. It is an ethos reminiscent of MIT professor Marvin Minsky’s philosophy of “messy coding” which favours writing extra code to fix bugs (programming problems) before they manifest rather than fixing problematic code at the source (Brand, 102).

The following quotation by David Thornburg which opens Brand’s chapter about MIT’s funding structure is a good example of the paradox of actually inventing the future:

“One of the worst things that Xerox ever did was to describe something as the office of the future, because if something is the office of the future, you never finish it. There’s never any thing to ship, because once it works, it’s the office of today. And who wants to work in the office of today?” (Brand, 155)

This concept is surely not a problem for companies accustomed to the common mode of advertising that promises consumers virtuous, luxurious, fulfilling products and services until they actually make the purchase, at which point the next product will take over this promise.

Today’s future

“Tinbergen found that the herring gull has a default rule: if you’re out of your nest and you don’t see a straw and there isn’t one in your mouth, then just wander around aimlessly. What you do when there’s nothing special to do always involves activity hoping something will turn up.” (Brand, 103)

This quotation from Marvin Minsky in chapter 6 of Brand’s book simultaneously brings to mind a meditative stroll, consumerism, and a resistance to idleness. Brand and Minsky were discussing how to deal with conflicting priorities.

“Work-life balance” is a trendy term used to describe the erosion of the division between labour and leisure due to communication technology bringing work into homes, and pockets through mobile devices. The initial separation of life from work came when technology provided citizens with leisure time. Prior to the industrial revolution life was mostly work.

The influential economist John Maynard Keynes predicted in 1928 that “by 2028 people wouldn’t need to work more than three hours a day”. Elizabeth Kolbert begins her book review No Time with this famous quotation by Keynes and goes on to describe theories from Brigid Schulte’s recent book Overwhelmed: Work, Love, and Play When No One Has the Time. One of Schulte’s theories is that the social status now associated with being busy has caused people to out-schedule one another. A second theory posited by Schulte relates to the personal conception of being busy — by never mentally taking a break, one could feel overwhelmed even while not doing anything.

The tired expression “time is money” explains and justifies the perceived value of work, because of the amount of compensation lost by not working. Viewing time as an economic entity has contributed to the shift that Barbara Adam calls chronoscopic time (Hassan, 90). This compression of time and space through technological tools has tangible effects on our lives. From companies such as Amazon asking employees to work over 80 hours per week to micro jobs that take minutes and pay pennies, the shifting nature of time is one aspect of the futuristic present that bears examination in relation to technology, society and culture.

What can a media lab do?

The humanities, like most academic disciplines, have shifted with scholarly trends leading to new areas of research such as the digital humanities, and the post-humanities. It’s important however not to diminish established disciplinary ground by changing a department too swiftly with emergent research. Similarly, enough interest in cross-disciplinary research could cause departments to merge.

Perhaps what a media lab can do is create a flexible enclave within which to house a research program that could reach across disciplines and explore new topics safely (without de-stabilizing the field it emerged from). The MIT Media Lab is the marital bed of ICT companies and researchers at the leading edge of technological development. Few other places can do what MIT does, nor do they need to. What media labs do at other academic institutions can vary based on the needs of researchers. Labs have a vital role to fulfill in promoting the humanities, social sciences and arts through the production of discourse that enables emergent critical thinking in these fields. The kinds of partnerships that keep funds flowing into MIT’s projects could work elsewhere, and may be worth seeking out given the movement at many North American universities toward a corporate business model. By allowing work from media labs to leak out into the high-tech world, ideas and ethos other than those of commerce could become visible. Ideally this would support citizens’ capacity to think reflexively, which is “a central requirement to the functioning of a vibrant democratic culture” (Ulrich Beck et al., as quoted in Hassan, 102).

A post-humanities lab would be a humanities-based lab that takes into account the work of theorists who have rightfully sought to destabilize the human exceptionalism historically apparent in academic discourse (and culture at large). Writers such an Donna Haraway, Bruno Latour, Cary Wolfe, Katherine Hayles and several others have written about cyborgs, non-humans and companion species in the interest of promoting a more complex conception of the interconnectedness of all entities within and beyond the scope of human understanding. Some theorists including Haraway and Claire Colebrook have moved beyond or rejected post-humanism in order to shift away from the anthropogenic nature of the term, preferring to focus on the social and economic conditions that have contributed to global inter-species concerns like climate change which are not perpetuated by all humans equally across cultures.

I like to think of posthumanism as reaching toward what might go beyond all that “human” implies. If we can transcend what keeps us trapped within the contradictions of capitalism maybe we’ll have a shot at a post-“future” future.

Works cited

Bell, Gordon and James N. Gray. The Revolution yet to happen, Beyond Calculation: The Next Fifty Years of Computing. Peter J. Denning and Robert M. Metcalfe (eds.) New York: Springer,1997. pp. 5 – 32. Print.

Brand, Stewart. The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT. New York: Viking Penguin, 1987. Print.

Ghosh, Amitav. Petrofiction, The New Republic, March 2, 1992. pp. 29 – 33. Web.

Hassan, Robert. The MIT Media Lab: techno dream factory or alienation as a way of life? Media Culture Society. Vol. 25, no.1, pp. 87-106. 2003 doi: 10.1177/016344370302500106. Web.

Kolbert, Elizabeth. No Time: How did we get so busy? The New Yorker. May 26, 2014. Web.

Schulte, Brigid. Overwhelmed: Work, Love, and Play When No One Has the Time. New York: Harper Collins. 2014. Print.

Additional Reference

Barbrook, Richard and Andy Cameron. The Californian Ideology. Science as Culture. Vol. 6 Issue 1. 1996. Web.

I have always found it deeply disturbing that images of housing in the “future” always involved these space-craft-like modules, where individual “units” of people could live separately and contained in their little bubbles, as though the dream of the future was to never have to interact unless it was absolutely necessary.

This was surely because the American Dream was each family to its own house, while the enemy Communists were “collectivized”. But the notion of “community” has suffered ever since; the “global village” is just consumerism on a mass scale, and everyone on the internet is part of some kind of “online community” which is non-existent IRL.

The “labor-atory”, a shared place of work, is essential to reversing the harmful trend toward alienation and division which predatory capitalism thrives on.

I liked your critique of some of the discourse on media labs and .This probe reminded me of our own Expo 67 and the super anthropocentric motto “Man and His World” and how the World Fairs seem to act as temporary media labs/trade shows that are also involved in the construction of national identity. I also wondered what happened to the expos since the 60s and we still have them but the themes have shifted, interestingly, from how many different ways that man can master spaces to the somewhat alarming need to apply technology to the crises of food shortage (“Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life: Milan 2015) and renewable energy (“Future Energy”: Kazakhstan 2017)