“WESTERN” MEDIA LAB / “EASTERN” ARCHIVE

The challenge(s) of establishing an alternative history archive from the Global South

The creation of the MIT Media Lab in the mid-80s pointed to a turning point in the way ideas surrounding research were not only conceived but also necessitated. It was in parallel with the widespread introduction of the personal computer, in addition to the fact that society was also very newly getting accustomed to (albeit beta versions of) the home video recorder, microwave ovens, the VHS cassette player, and the CD — and of course, the rise of electronic music. The mid-80s were when Western society was introduced to technology in their homes and every day lives en-masse and the culture of technology-inspired technology-based consumption was kickstarted. A new market had new needs, the public needed to make sense of it all while learning it so it could start consuming it, and institutions of all sorts needed to incorporate technology in order to step up their game. Robert Hassan’s article “The MIT Media Lab: techno dream factory or alienation as a way of life” sheds light on this cultural revolution that occurred and how the MIT Media Lab was propelled by these developments in establishing and pursuing its mandate. I’m interested in one point that Hassan raises in his article, about how the MIT lab navigates the gap between the “developed” and “undeveloped” countries; how “It actively works from both ends of the gap to connect developed with developing countries and IT-rich with IT-poor countries in the quest to enrich world culture(s) and to enhance our collective self- knowledge.” (Hassan, 89)

While the MIT Media Lab can essentially be understood as an organized, sponsored space for highly skilled quantitatively discipline-trained thinkers to essentially work creatively as thematic inventors, most media labs that have popped up since then don’t benefit from the same access to funding, human and technical resources, nor as captive of an audience — clearly this may also have something to do with how much it invests in marketing. However, corporate sponsorship also means that it also has the pressure to produce commercially viable products (Hassan, 93). Steward Brand refers to this as “the entire apparatus” of the media lab. (Brand, 7) Hassan asks two specific questions that I inspire me to begin the discussion of my probe. He asks these key questions that inspire my line of inquiry as I navigate the process of creating a digital archive linked to my PhD research. He asks: “Where do the [MIT] Lab and its work fit in the larger picture of a globalizing capitalism whose aggressive expansionist logic is dialectically interwoven with dynamics of the ICT (information and communications technology) revolution? Moreover, what are some of the possible social, cultural and ontological consequences of ‘being digital’ within a hypermediated digital ecology of interconnectedness?

INTRODUCTION

My doctoral research project explores the participation of Pakistanis as foreign “Fedayeen fighters” (freedom/resistance fighters) in the Palestinian armed struggle under the Palestinian Liberation Organization (P.L.O.) during the seventies and eighties. Existing literature barely mentions the participation of foreign fighters as Fedayeen in the Palestinian armed struggle, and my research was prompted by my discovery of elderly Pakistani men I found living in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon several years ago, who it turned out, were former Fedayeen. My research has taken me to Pakistan and Lebanon where I’ve been attempting to track down former fighters and those who knew them, conducting interviews and navigating the landscape of memory, while in parallel, trying to find and navigate scores of primary source data ranging from documents to photographs to party propaganda, newspaper and media archives, cemeteries and other physical places and/or sites of relevance.

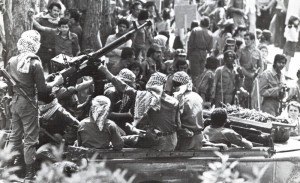

PICTURED ABOVE: Fedayeen fighters of various nationalities, with the PLO, in Lebanon during the Lebanese Civil War (Source: Unknown). This is an example of one of hundreds of photographs that I am discovering as I research that would contribute to a the photographic branch of the archive that seek to create.

Thus, I aspire to realize a media-lab based digital humanities project for my research-creation PhD project, to be known as a “Fedayeen Archive”. At Concordia University, I aspire to house my archive project, of which discourse analysis and anthropology of media are important methodological focal points, under the new Global Emergent Media Lab, which “combines media ethnographic research and experimentation, digitization and curation projects,” (GEM lab website) in additional to theoretical analysis and debate. I am motivated by the ideas of archive and narrative in the digital humanities. For my PhD research I’m navigating large amounts of non-digital resources in numerous countries and languages. At the same time I have been going through the abstract process of attempting to identify factors contributing to the general lack of Palestinian and Lebanese digital resources and archives. I seek to ultimately create a subject-specific digital archive, yet, in order to determine whether such a digital archive project is even feasible, I’m currently navigating the questions: what are the perimeters of collection of data in Palestine studies? What historical resources/archives relating to Palestine and the Lebanese Civil War exist online, in the digital realm, and who put it there? Why is there so little online?

In his key questions which I noted earlier, Hassan refers to the expansionist logic of aggressive globalizing capitalism as being inherently linked to the output of a media lab, and as a whole, it can be easily argued that the Western model of funding academic institutions and research should be regarded as a direct reflection of this. Secondly, when Hassan asks about social, cultural and ontological consequences of “being digital”, one must ask who the production of a particular “knowledge” or “narrative” or “fact” or “data” benefits? Information and facts as we know are socially constructed as the French sociologist Emile Durkheim has explained. My own research project is situated at the intersection of two distinct, ideological, “controversial” historical frameworks: the Cold War and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, there are a series of additional essential questions that I ask. Why was the extensive participation of foreign fighters in the Palestinian armed struggle largely excluded from both of the dominant narratives (Palestinian and Israeli/Zionist) on this period? I hypothesize that it was in neither of their interests to acknowledge the participation of foreign fighters because both Palestinian and Israeli narratives rely on the nationalist position. Palestinians benefited from establishing the position of a strong unified front of resistance fighting for the right of return to a homeland, and Israelis benefitted from identifying a single enemy: the Palestinians, as terrorists. Literally all Israeli books and articles about the Fedayeen refer to them as Palestinian terrorists guerillas, whereas the Palestinian texts refer to them in the sense of a more romanticized nationalist freedom fighting hero.

ABOVE: A short rough cut of an interview I conducted with a Palestinian widow of a former Pakistani fedayeen fighter with the PLO. This is a sample of the type of original material my archive project encompasses and attempts to illustrate the depth of how much this new material needs to be studied.

NARRATIVE THEORY

Roland Barthes outlined a structuralist narrative theory of five codes[1], as he outlines in his analysis of Balzac’s short story “Sarrasine” in his book S/Z, enables one to establish/structure/assign meaning to texts, and thus equips readers with a tool to read texts as essentially codified assemblages of meanings. How can Barthes’ theory of codes be used to read the problematic of limited Arab historical perspectives? Are Lebanese archives are automating a historical processes and/or what is the relation? Are the digital humanities Euro-centric, and if so, why? What role do digital archives play in studies of the Palestinian armed struggle during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990)? Are epistemological [nationalist] claims in Palestinian studies during this period ethical claims? How can one approach using data from non-digital written and visual texts into a digital humanities analysis and project? Who created this information that exists online? Where is most of this information coming from? Why do some events or periods of the wars in both the colonial and post-colonial periods in the Global South have more available information than others? Of existing limited information that exists in the digital sphere, who chose what got digitized? If digital archives are only a “new” medium for “existing” information, how then can digital archives facilitate new understandings of a historical event, without new information? Are Western institutions where DH is centralized, controlling knowledge production/manufacturing in “the East”?

In his preface to the book The Media Lab, Stewart Brand writes that at the MIT Media Lab, “the term ‘media’ means electronic communications technologies, period.” (Brand, Preface, xiv) Using this definition of media, is how we can understand that “media labs” as spaces and places of information production have evolved — researchers or scholars engage with technology(ies) to produce new information. So considering this, the archive that I am attempting to create in order to “produce” new knowledge that would enable scholars and publics to re-learn and re-consider something that has been (exclusively) established in the public domain, requires an engagement with electronic communications technologies on all levels from research to digitization to organization to analysis to generating data to dissemination of data and sources.

NARRATIVE

The crisis of an inadequate presence of Palestinian and Lebanese textual corpora resources in the digital humanities prompts me to question ideas of narrative as forms of representation versus a manner of representation. The inherent problems of narrative and representation in my research fit well within the theoretical framework of Roland Barthes’ structuralist narrative theory; he explains that all texts are either open or closed; open meaning that they can be unravelled, or closed in that they only have one narrative thread. Therefore, Barthes’ view that text can be unravelled also meant that text is reversible in that it has an indeterminable beginning and therefore can be accessed from a multiplicity of entry points. The process of unravelling this narrative or text can lead to numerous possible meanings, and depending upon which angle or position from which we viewed the text, a meaning or perspective can be established, but that this process is limitless and the number of meanings that can be established is essentially infinite. He narrows this down to five codes that can be found in any narrative: Action, in which action produces resolution; Enigma, in which the tension created in the narrative leaves an open-ended question; Symbolism, where new meanings are created from situations, conflicts or conflicting ideas; Culture, which is determined by the reader or audience’s social knowledge and way of thinking; and finally Semantics, meaning that a narrative can have additional significances or subtexts[2]. Hence, if Barthes’ theory of narrative is used to approach the problem of limited digital archives in Palestinian historical studies, it could be said that Palestinian historical narrative is an open text that has been approached from a limited number of perspectives, and by studying transnationalism in the Palestinian armed struggle by using primary and secondary materials and sources that originate from outside of the dominant Arab and Western/Israeli spheres of research, the five codes as Barthes describes, with which we can establish meaning and deconstruct dominant Palestinian narratives will offer dynamic intrinsic value. As David Bodenhamer writes, “Increasingly, historical research focuses on ideas of movement and encounter, on what happens in the spaces between cultures, on processes of transculturation, and on how differently separate cultures perceive the worlds they inhabit.”[3] As such, this Bodenhamer quote perfectly sums up the historical space within which I situate my research, and how approaching the Palestinian armed struggle from the perspective of non-Arab leftists in solidarity with the anti-imperial struggle triggers new interpretations of the Palestinian armed struggle and Lebanese Civil War as an arena for a transnational anti-imperial struggle.

This idea of spaces between cultures as Bodenhamer describes it, can also be extended to the issue of participation in digital humanities as a discipline. The overwhelming number of digital humanities scholars being North American and European does prompt the question, are the digital humanities white, or simply western? Clearly the Digital Humanities as a discipline or phenomenon hasn’t yet taken root in serious terms among scholars in Lebanon, Palestine and Pakistan, and this may be for a number of reasons. Why are the digital humanities so Euro-centric and is race and ethnicity a factor in the lack of Middle East archives on line? Or is it simply that the first world has the institutional, academic and governmental infrastructure in place to contribute to digital humanities, versus a lack of this in the developing world? Perhaps it’s both. In her article, “Why are the Digital Humanities So White? Or Thinking the Histories of Race and Computation” by Tara McPherson, she writes: “… detailed examinations into the shifting registers of race and racial visibility post-1950 do not easily lend themselves to observations about the emergence of object-oriented programming or the affordances of databases. Very few audiences who care about one lens have much patience or tolerance for the other.”[4] Separately, it’s important to consider that archives emerge within institutional structures, whether state or national, and the lack of a Palestinian state, as well as the lack of Lebanese and Pakistani infrastructure, are major reasons that archives and resources are not indexed, digitized or even fully known. Overall, indeed the Fedayeen Archive project I seek to create would require such extensive resources to achieve, even if I gain the logistical support of a media lab based at a Western institution to house the archive, the fieldwork and costs associated with identifying, generating and digitizing information to form the key corpus of the archive proposes significant challenges as they are largely unidentified materials scattered in numerous countries, in numerous languages. Getting this archive off the ground however could be a significant contribution to Palestinian Studies, Middle East Studies and anthropology, sociology and history, because it could function as a “live” archive-in-progress: while I would establish the archive with the Pakistani element of transnational participation in the Palestinian armed struggle under the PLO, other and future scholars working on identifying other foreign participants as Fedayeen to the Palestinian armed struggle during the same period (and there were many) could also house their material in the archive and the future possibilities for comparative analysis and knowledge production could become infinite.

[1] Hermeneutic; Proairetic; Semantic; Symbolic; and Cultural

[2] Barthes, Roland, S/Z, New York: Hill and Wang, 1974

[3] Bodenhamer, p.25

[4] McPherson, Tara, “Why are the Digital Humanities So White? Or Thinking the Histories of Race and Computation”, Debates in the Digital Humanities, CUNY, Site accessed on November 20, 2014 <http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/29>

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barbrook, Richard, and Andy Cameron. “The Californian Ideology.” Mute 3 (Autumn 1995).

Barthes, Roland, S/Z, New York: Hill and Wang, 1974

Bodenhamer, David J. ‘The Spatial Humanities: space, time and place in the new digital age’, in History in the Digital Age, Routledge: New York, 2013

Brand, Stewart. The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT. New York: Viking Penguin, 1987. chapters 1, 6, 9, 13.

Hassan, Robert. “The MIT Media Lab: Techno Dream Factory or Alienation as A Way of Life?” Media Culture & Society 25 (2003): 87–106.

McPherson, Tara, “Why are the Digital Humanities So White? Or Thinking the Histories of Race and Computation”, Debates in the Digital Humanities, CUNY, Site accessed on November 20, 2014 <http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/29>

Global Emergent Media Lab website, Site accessed November 14, 2015, <http://www.globalemergentmedia.com>

I’m wondering what role shared language plays in the “Western domination” of the Digital Humanities. I’m assuming your archive would be framed in English; is it accepted that Palestinian and Lebanese scholars will speak English and present their public research in English? Or is it accepted that they present in Arabic and choose to have it translated or not. I’m asking this as it relates to my own post on the Hegelian wound; is the universality of English a given as, say, the “anchor language” of your archive? Or will there be a multi-language component to enable all users to access the data? I have always felt that the overwhelming presence of English on the web determines SO much of how we see it — the amount of information in modern Greek, for example, is very small, and most educated people in Greece simply resign themselves to accessing sites in English. As someone interested in the role of translation/national languages in the peace process, I’m interested in your take on this issue.

Great probe! How you applied Hassan’s analysis of the IT-rich and IT-poor divide.

On the subject of diversity in media labs/digital humanities, here’s an article (from yesterday) on diversity at the MIT media lab: https://medium.com/mit-media-lab/30-years-of-research-on-gender-and-equality-at-the-mit-media-lab-3ec534fc52a9#.rowoffeyz