Mosaic and Collage in Jonathan Lethem’s “The Ecstasy of Influence”

Jonathan Lethem’s essay “The Ecstasy of Influence”—a tissue of appropriated passages from writers ranging from Sandra Day O’Connor to Mary Shelley—bears the subtitle “a plagiarism,” but it is an odd word to describe the piece. Reading through the assiduous inventory of references in Lethem’s closing “Key: I Is Another” (68), the reader recognizes that the one thing “The Ecstasy of Influence” is not is an act of plagiarism, at least in the usual sense of the term, such as in the definition offered by Laura Murray: a “use or reuse of [another’s] words or ideas without acknowledgement” (174, original emphasis). At one point in his notes, Lethem reflects on what would have been the case in the text “had I been an ordinary cutting-and-pasting journalist” (70), and indeed it is clear that he is doing no mere cutting and pasting here; he even includes a “Key to the Key” (71) in which he acknowledges those who have had the mere idea of a text collage before him, among them Walter Benjamin in his unfinished Arcades Project. Lethem writes that “[a]ny text is woven entirely with citations, references, echoes, cultural languages. . . . The citations that go to make up a text are anonymous, untraceable, and yet already read; they are quotations without inverted commas” (68), but of course there is nothing “anonymous” or “untraceable” at all about the passages borrowed here.

Lethem places his essay in the context of the multivocal works of pastiche that it discusses, framing the work itself as likewise “ecstatically” reveling in and integrating the catholic context of the writers who have influenced it. He writes of the “‘open source’ culture” (60) of jazz and blues, the “allusion and sublimated collaboration” that are the “sine qua non of the creative act” (61), and the problematic ways in which intellectual property figures in both the “market economies” and “gift economies” (65) that are so basically at odds with one another. Lethem’s text is thus an anthology of the creatively liminal, radical, and egalitarian. To suggest that the text is in some way also a “plagiarism,” though, is to suggest at least one of two further things about it: first, that Lethem intends to deceive in some way, that he would have the reader assume that at least some of the appropriated material is his own, and second, that he intends to confuse or obscure the distinction between his text and its context—not just an appropriation but a sort of absorption of these other voices and works, smoothing over the lines between his own words and those of others. We can dismiss the first of these, as with the thoroughness of its documentation Lethem’s piece is clearly intended to deceive no one: he means to leave us in no doubt about the source of any of the lifted passages. He does not actually “plunder” either the editions or the visions of anyone: he attributes everything, operating within a citation economy rather like the one in place in academic writing, clearly laying out what belongs to him and what does not, what remains unchanged and where he has altered things and intruded upon the text.

What is at stake here, then, is the relationship between text and context, between the individual textual fragments and the work as a whole that Lethem constructs. I want to suggest that he deals in the essay with two quite different forms of composite construction, one of which is quite unlike the collage form with which he explicitly identifies “The Ecstasy of Influence”; the riot of assimilations and appropriations that he describes is, to borrow another metaphor from the visual arts, more like a process of mosaic construction, a subsuming of fragments into a unified whole to which each fragment is subordinate. Without the key at the end of the text, that is indeed exactly what “The Ecstasy of Influence” itself seems to be, as Lethem modifies his borrowings to dovetail them seamlessly with what is ultimately a continuous piece in terms of voice, tone and perspective. Only by incidental recognition of one or another passage along the way could readers know that the text is a mosaic comprising fragments rather than a homogeneous work, a little like the effect of viewing a mosaic at a distance rather than up close. The effect of the “key” at the end of the text, though, is more than just to bring the viewer close enough to the mosaic to view the fissures between the fragments; it is to destroy the unity of the text altogether, to break the pieces apart and resituate each within its original textual and authorial context. This is ultimately the effect of collage rather than mosaic construction, of fragments “placed in juxtaposition” (“collage,” OED Online) rather than uniting to comprise a “variegated whole” (“mosaic,” OED Online 2b). My goal in highlighting these ideas of collage and mosaic composition in this probe is to point out the manner in which Lethem’s text underscores the differences between these two kinds of composite creation by embodying and demonstrating both ways of understanding text and context, and to offer us a potentially useful vocabulary for talking about fragments in compositional context more generally.

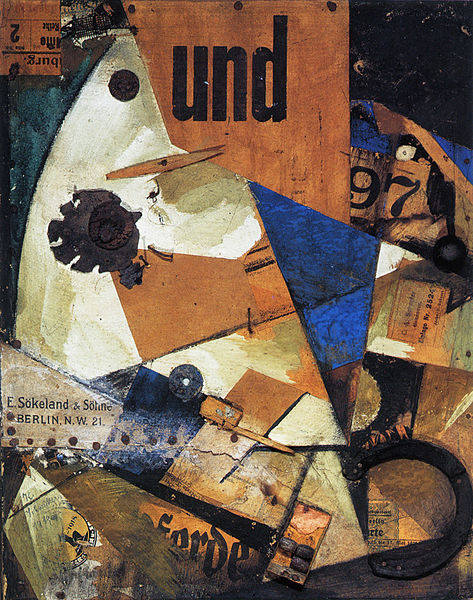

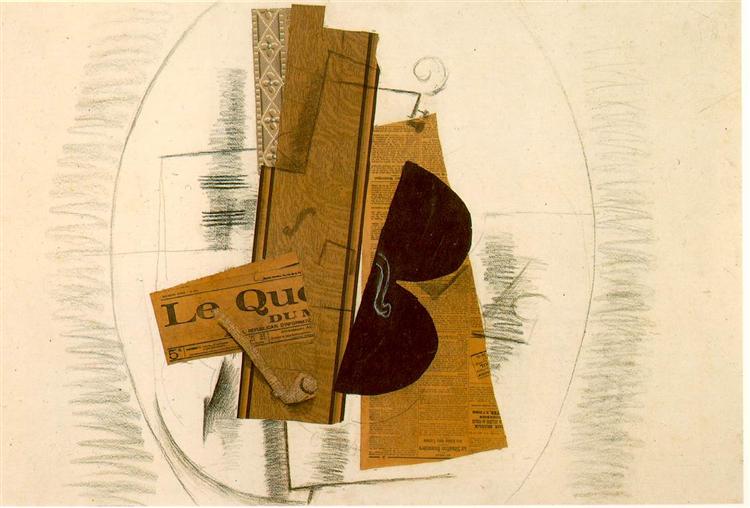

Lethem refers to his work here—the result of a process by which he “stole, warped, and cobbled together as [he] ‘wrote’” (68)—as a “collage text” (71). This metaphor aligns Lethem’s text with notable works of visual collage such as those by Picasso, Schwitters and Braque in which fragments are “placed in juxtaposition” (“collage,” OED Online) and “photographs, news cuttings, and other suitable objects are pasted onto a flat surface, often in combination with painted passages” (Chilvers, “collage”).

Pablo Picasso, Still Life With Chair Chaning (1912): http://www.arthistoryarchive.com/arthistory/cubism/images/PabloPicasso-Still-Life-with-Chair-Caning-1911-12.jpg

Kurt Schwitters, Das Undbild (1919):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:DasUndbild.jpg

Georges Braque, Violon et Pipe (Le Quotidien) (1913-1914): https://www.wikiart.org/en/georges-braque/violin-and-pipe-le-quotidien-1913

In each of these collages, the frame around the canvas unites the gathered fragments in a sense, but they do not form a single coherent image. Their differences of origin, medium, shape, style, etc. remain in place, and in fact it is precisely this emphasis on juxtaposition and discontinuity that establishes the form of the collage itself, what Lethem in his piece calls “the art form of the twentieth century” (59, original emphasis).

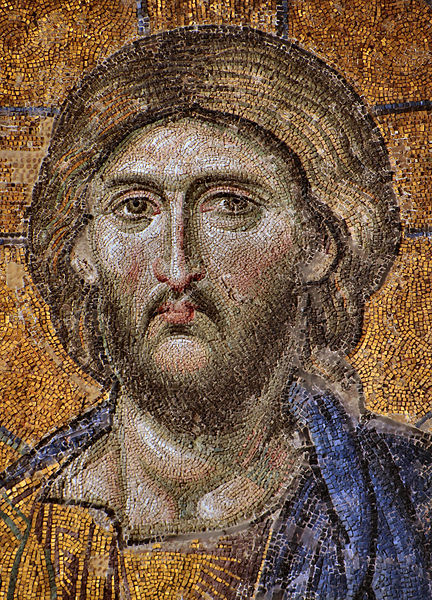

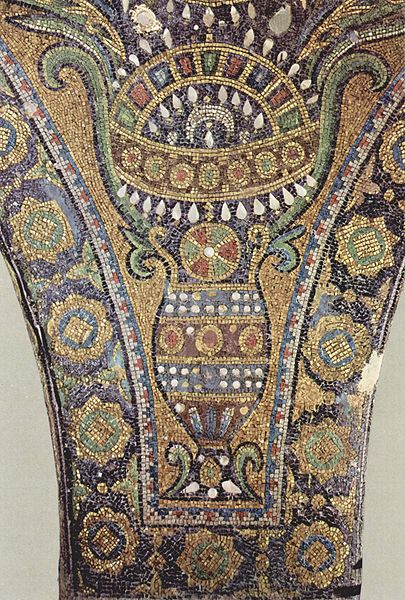

“The Ecstasy of Influence” is not constructed like a collage, though, at least in its main body. Lethem carefully trims the edges of these textual cuttings so that they fit seamlessly with the rest, coming together as if produced by one voice. He obscures the discontinuities, the harsh lines and overlapping corners of the constituent elements of the text, and what emerges here instead has more affinities with a mosaic image than a collage, “a variegated whole formed from many disparate parts” (“mosaic,” OED Online 2b) rather than a juxtaposition of discontinuous fragments:

Christ Pantocrator mosaic, Hagia Sophia: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Christ_Pantocrator_mosaic_from_Hagia_Sophia_2240_x_3109_pixels_2.5_MB.jpg

Perso-Roman floor mosaic, Iran: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mosaic01.jpg

Mosaic, Dome of the Rock: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arabischer_Maler_um_690_002.jpg

In a mosaic, the “variegated whole” is a coherent, consistent image in the aggregate; even in cases in which each fragment of a mosaic is itself a complete photographic image, each is nonetheless fully integrated into the larger image, comprising it harmoniously alongside all the others. Where the context of collage fragments is one of discontinuity and contrast, of visual cacophony, the context of mosaic fragments is one of pictorial unity, of visual consonance.

Lethem writes of works with both mosaic and collage constructions in “The Ecstasy of Influence”; the “freely reworked” (60) mosaic composites of blues and jazz and other musical mash-ups contrast with collages like the “vertiginous mélange of quotation, allusion and ‘original’ writing” (61) in Eliot’s The Waste Land. Dealing with both of these forms, Lethem’s own text is a mosaic until the appearance of the key at the end, where, with the inclusion of the citation apparatus, the lines between the textual fragments become visible, and the text breaks apart, with each text attributed to its original author and the piece as a whole reframed as an anthology, a collected and arranged miscellany. What had been a mosaic construction dissolves into a collage of juxtaposed textual fragments, and while there are common themes among these passages to be sure, their discontinuity and polyphony is apparent in the various diverse discourses from which they are drawn: literature and literary criticism, law, the writings of experimental musicians, filmmakers, political figures, and so on.

The text describes and represents both of these contrasting forms of composite construction, as the key at the end restructures the whole by reframing the relationship between text and context throughout, isolating the fragments and dissolving the illusory image of the coherent essay by a single author. This is ultimately why the formal and structural distinctions between mosaic and collage construction are of interest to us here, as we address the questions of authorship, reproduction, and attribution at work in the discursive “confusion” between different modes of integration, such as the conflict between plagiarism and copyright infringement that Laura Murray describes. Lethem’s piece prompts us to consider how different methods of incorporation and attribution construct different text/context relationships that prove consequential for the interpretation of composite works and the assessment of the specific roles of fragments in context. We might consider, for example, the politics of Lethem’s shifting relationships with these other writers, whose grandmothers he has been careful not to appropriate (69), but whose works he has nonetheless modified as part of a relationship that recruits and subordinates them. Lethem operates within a citation economy, but he does so only after sustaining the illusion that these secondary materials are his own, and the two ways of appropriating contextual material on display here—assimilation into a mosaic, even with peripheral attribution, on the one hand, and inclusion, with distinctions of authorship and voice nonetheless documented and preserved, in the clamour of a collage on the other—highlight what is at stake when, to various textual and political ends, we quote and integrate the contextual discourse surrounding our work.

Works Cited

Chilvers, Ian. “collage.” The Oxford Dictionary of Art. : Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference. 2004. Web. 8 October 2016.

“collage” OED Online. Oxford University Press, September 2016. Web. 8 October 2016.

Lethem, Jonathan. “The Ecstasy of Influence: A Plagiarism.” Harper’s (February 2007): 59-71.

“mosaic” OED Online. Oxford University Press, September 2016. Web. 8 October 2016.

Murray, Laura. “Plagiarism and Copyright Infringement: The Costs of Confusion.” Caroline Eisner & Martha Vicinus, eds. Originality, Imitation, and Plagiarism. <http://quod.lib.umich.edu/d/dcbooks/5653382.0001.001/1:4/–originality-imitation-and-plagiarism-teaching-writing?g=dculture;rgn=div1;view=fulltext;xc=1 – 4.2>