The leaky life & times of the AA battery inside the Residual Media Depot: A snapshot of battery life & faded battery power

The area of concern I am focused on is e-waste and specifically, dead batteries. What do dead batteries have to do with degradation and loss of materials within a literary archive, within a museum collection, or in this case, within the Residual Media Depot (RMD)? Before I answer that question, I will orient you the space within the RMD dead batteries are drawn from.

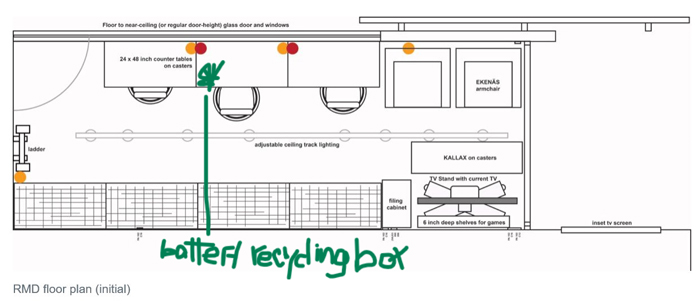

RMD floor plan + battery site

As is described on the RMD website and as Professor Wershler has mentioned, “the physical space of the RMD is a former depot for photography equipment.”

Peripherals up close

As we have seen, the RMD collection includes: game consoles, game boxes, a work bench, hardware, tools, cables, file cabinets, TVs and other monitors and seating. Below eye-level and beneath the work bench, as indicated in the floor plan above, there are storage boxes containing cords, power bars, rubber gloves, nylon cable ties, Q-Tips and so on. The golden nugget for this probe? A single blue recycling box which keeps used batteries. While you can’t make the batteries out in the image here, the box itself and some (or many) of the batteries within it was inherited from the aforementioned photography depot.

Battery life

So, what do dead batteries have to do with degradation and loss of materials within a literary archive, a museum collection, the RMD?

The image of a museum collection as being “timeless, without end,” as Lubar et al. discuss in “Lost Museums,” typically does not foster thinking on the nuts and bolts of production nor specifically on batteries. A battery is a “helping” consumer product. No matter how far in the background batteries and dead batteries may be in view of a museum or of research collections, they have an important place in helping to make parts of collections and the tools of collection maintenance to simply work. Yet, batteries (and other power sources) are crucial to making the media devices and tools we use actually work.

There is an element of language use and speaking I wish to consider. How can we speak about collections and management of them in a way that includes all of the “moving parts” so as to make visible their presence when alive (or working,) or dead? As I mentioned in an earlier probe, I am interested in design (and therefore, in ways of speaking) that considers media devices, peripheral items and power sources from “cradle to cradle” rather than from “cradle to grave.” (McDonough & Braungart.)

Charles Acland breaks into within his discussion of Harold Innis’ identification as a “dirt economist.” He writes:

At one level, media commodities are but a surface manifestation of a deep structure of materials and their movement. Our analytical capabilities would be impoverished if they only charted the topsoil and ignored the geological layers beneath. Pursuing the dirt and depth of cultural economies should not dissolve medium specificity, but should help us conceptualize and understand the full systemic entwinement of our media objects with resource economies. (Acland, 9)

Museum life

“Museums might bend, rather than break” (Lubar et al., 8)

Lubar et al. address the perceived monolithic yet fragile existence of museums and assert that looking ahead, “museums might bend, rather than break,” – a salient proposal. They quote Sheila Brennan, who “urges us to ‘think radically’ about collections, using them rather than storing them,” (Lubar et al., 10) in her blog article, “Making room by letting go: A look at the ephemerality of collections.” The recommendations Brennan makes are so important to community building and museum sustainability. In reading them, I couldn’t help but to imagine the environment also fitting into this vision. Building on Lubar et al’s work, I would assert that museums are not only smooth bendable surfaces, but they are also porous with human interaction and traffic. They are located on soil or concrete and are susceptible to weather conditions, to nature. Museum structures also flex with air, crack with the cold and require heating, power and people to turn the lights on and off each day.

Nam June Paik, Zen for Film (1985)

Lubar et al. make reference to Nam June Paik’s Zen For Film (10) as being a guiding conceptual inspiration when it comes to thinking on new possibilities for the museum. For any cultural collection, I propose we consider not just the surface area of the white box as seen in Zen for Film to re-envision how collections function, but also that we consider and imagine “invisible” parts of this silent film as inspiration. Some of those “invisible” parts can include the small gritty pops of dust in the light passing through the film projector, the sound of one’s own breath and other sounds as the film plays, and the tools and materials that helped to make the film a reality.

Battery life includes dust, clumps, dumps

In his presentation to us about the Richler Reading Room, Professor Jason Camlot talked about getting to understand Richler’s library and an author’s library in general. He asked, “what is the mess of it? How does it relate to other things?” The dead batteries found within the RMD are the literal mess and a retired power source from within the collection. A somewhat uncontainable (for they are gathered in a box), unruly assemblage, as John Law might suggest.

As a function of the concept of “mess”, dead batteries are items that are not a central focus in the everyday. They are by their nature, “peripheral” (but not peripheral) to various electronic tool functions.

“Otherness is absence that is not acknowledged.” (Law)

…Some of the possible styles of Othering:

There is the invisible work that that helps to make a research report.

There is the uninteresting, everything that seems to be not worth telling.

There is the obvious, things that that everyone is taken to know.

And then, to ratchet up the metaphor and what is at stake, there is everything that is being repressed for one reason or another. (Law, 8)

“Otherness is absence that is not acknowledged,” says John Law (8.) The dead batteries from the RMD do undergo a kind of “othering” as Law describes in the paper “Making mess with method.” To echo Law’s possible styles of othering:

- There is the invisible work batteries carry out that helps make tools and devices function.

- There is the uninteresting in batteries. When they work, everything seems to be not worth telling.

- There is the obvious, things that everyone is taken to know about batteries.

- And then, to ratchet up the metaphor and what is at stake, there is everything that is being repressed when we speak about batteries for one reason or another.

The leaky life & times of the AA battery inside the RMD…

Leaky, dead batteries have everything to do with degradation and loss of materials within a literary archive, a museum collection, and the Residual Media Depot. While there are various drop-off points on the Concordia University downtown campus for dead batteries and e-waste, to deal with dead batteries in the everyday, (whether in a university research collection, museum, business or home setting) carries a less than urgent quality. Yet, is there any way we can we find a way to make visible the presence of tools we typically invisiblize or “other”? Can we find a way to speak of dead batteries and other forms of e-waste in a way that imbues not only their commercial and function value, but also their environmental impact and cost in a way that makes our academic, creative, curatorial efforts at the forefront of an expanded preservation and vitality? That acknowledges that they are drawn from and will ultimately be returned to the ground and the air?

Works cited

Acland, Charles R. “Dirt Research for Media Industries.” Media Industries Journal, 1.1, 2014. pp 6-10. Brennan, Sheila A. “Making Room by Letting Go: A look at the Ephemerality of Collections.” Preservation Leadership Forum Blog. forum.savingplaces.org/blogs/special-contributor/2014/08/12/making-room-by-letting-go-a-look-at-the-ephemerality-of-collections. August 12, 2014.

Camlot, Dr. Jason. Presentation to ENGL-645, September 12, 2017.

Law, John. “Making a Mess with Method.” Lancaster: The Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University, 2003.

Lubar, Steven, Lukas Rieppel, Ann Daly, Katherine Duffy. “Lost Museums,” Museum History Journal, 10:1, 2017.

McDonough, William and Michael Braungart. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. NorthPoint Press, a Division of Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York. 2002.

Wershler, Dr. Darren. “What’s In A Name? This is not a media archaeology lab. This is not an archive. This is a research collection.” Residual Media Depot website: residualmedia.net/whats-in-a-name. July 21, 2016.