The post Boot Camp: Count von Counterprotocol appeared first on &.

]]>“We can count, but we are rapidly forgetting how to say what is worth counting and why.”

-Joseph Weizenbaum (16)

Sesame Street’s Count von Count—a Bela Lugosi-style Transylvanian vampire plutocrat muppet of ostensible Romani origin with obsessive compulsive tendencies—holds a worldview which is essentially quantitative.1 Like the wielder of a golden hammer, to whom everything looks like a nail, the Count’s déformation professionnelle limits his outlook to those things which are countable.2 This myopia is cause for concern in instances where his own emotions subside into the cold logic of numerical abstraction; where his taste for counting comes at odds with the sensual body (as portrayed with Cookie Monster, or on a picnic); where he thwarts the creative endeavours of others; where he is faced with the impossible task of enumerating chaos; or where his love of numbers trumps the desires of a significant other.

This Boot-Camp approaches a widespread diagnosis of this Count Syndrome—a particular worldview shaped by the proliferation of numeric abstraction—afflicting those of us affected by digital culture. It further proposes a treatment in the form of a computer virus.

Count von Counterprotocol is a (theoretical) program designed to render explicit the numerical, binary coding that makes up digital media. The malware furtively infiltrates one’s personal computer but does not corrupt or alter any component of the machine. Rather, the virus commands that any and every file opened on the computer be executed as a video of the Count reading aloud each of the file’s bits (ones and zeroes) in sequence. As even a tiny file of 1kb contains over 8000 bits, the virus impels a tedious, protracted reading of digital media that imparts a decidedly limited view of one’s files along their numerical lines. The process insists against interpreting or reading files via the sanctioned protocols that make them comprehensible to human subjects. In ‘fucking up’ these protocols, the program obliges a raw purview of the underlying codes that allow for digital systems to control and order flows of information.

In 1976 the renowned humanist technologist Joseph Weizenbaum put forth an argument now familiar to critics of digital culture. He critiqued the current state of science and technology as mounting from a “passion for certainty” and “quest for control” (126). This concern for unambiguous and governable systems, aside from being consciously developed for technical instruments, stems from a set of unconscious methodological and ideological biases that political theorist Isaiah Berlin recognizes as a heritage of the platonic ideal, in which “all genuine questions must have one true answer and one only, all the rest being necessarily errors” (3). This dominant, binary outlook permits only claims that abide by the law of the excluded middle (true or false) and exclusive disjunctions (either / or operands). If this worldview saw Galileo affirm the centrality of mathematics—that ‘language of the universe’— in the seventeenth century, the same worldview carried the “influence of mathematical logic” into modern cybernetics (Wiener 12).

A harbinger of the digital computer, the field of cybernetics aimed in the twentieth century toward the mechanization of symbolic reasoning. Through feedback, systems analyses, and techniques of control, cybernetics developed a certain quantitative outlook of ‘systems’ as diverse as telephone networks, ecosystems, and human bodies. This mechanized, measured perspective has deeply infected metaphysical understandings of reality, as a dominant force that Jaron Lanier calls Cybernetic Totalism. Here, the self is to be understood as a mere information processor, or the natural environment as a plain set of measurable, biological processes, in what entails a considerably dumbed-down worldview that edits-out unmeasurable complexities and unknowables. This simplified, limited technological outlook based on the centrality of certainty, neglects what Weizenbaum meant when he proclaimed that “there is an outer darkness” (127)—a deep and unapproachable uncertainty that is, as Bifo Berardi and Alessandro Sarti have written, an “intrinsic ontological feature of natural reality” (60).

Such vast unknowables and unthinkables tend not to find representation in computer software, probably for reasons of practical utility (I wouldn’t want MS Word to constantly remind me of the fundamental mysteries and paradoxes of the universe). However, this lack of transparency in digital systems—heavily structured control-machines—is coloured by these larger ideological imperatives toward certainty and order. Based ultimately upon binary systems (what Kittler reduces to its material “voltage difference”3) digital computers necessitate a controlled engagement along binaries: either on, or off. As critic Jan Verwoert has observed, “it is a system based on the constant repetition of either/or choices” (18). In the streamlined efficiency of its interfaces is a “tendency,” as Alexander Galloway explains, “for software to priviledge surface over source” (291). And in this privileging does software hide the biased protocols of its control systems, in what Wendy Chun calls “software’s uncanny paralleling of ideology” (22).

Galloway has developed a sophisticated study of protocological ideology within digital culture.4 At its most basic form, these are standardized technical protocols that sanction access on the Internet, as seen in the functioning of informational systems like TCP/IP, DNS, UDP, and HTTP.5 These systems enable interaction between entities online, but also restrict how and what type of information is shared. Such highly-regulated control structures often go unseen in engagements with the Net—commonly thought of as an open-access, horizontal field devoid of hierarchical powers. Galloway here provides a critical lens with which to see the general functioning of power in digital networks. More than just rules and regulations for online activity, protocol represents ideological forces that underlie these networks.

Significantly, Galloway’s framework also accounts for forces of political resistance against protocols.Here, through what he terms counterprotocol, critical rifts can be torn into both the technological and, hence, ideological structures of digital systems. Protocols, then, allow for their own undoing: not merely a hegemonic system, “protocol is synonymous with possibility” (244). Counterprotocol practices are modes of resistance within-but-against protocological structures. They are practices that enable the penetration of a system in order to exploit it. Not the mere wrench-in-the-machine of neo-Luddism, counterprotocological activity infiltrates and works with ‘the machine’ in order to undermine and leverage its power.

It is this disruption that the Count von Counterprotocol virus aims toward. It renders visible (though absurdly and incomprehensibly) the basic structures of computation, and the protocols that shape ideological engagement with them. The virus compels a raw look at a file’s underlying material structure – foregoing the computer’s designs toward communicating information, in favour of representing its more ‘pure’ data. Like Moretti’s distant reading, it is limited to the degree that “it provides data, not interpretation” (72). In rendering mere binary code, though, it attempts to make visible what sociologist Manuel Castells has called the “unseen logic of the meta-network” (508), and consorts with Geert Lovink’s call to “revolt against the mathematical shapes of networks” (23). It attempts to open a critical fissure through which the fixed definitions and impenetrable logic of the computer may become questionable and uncertain.

Works Cited:

Berardi, Franco Bifo and Alessandro Sarti. RUN Morphogenesis. Kassel: Documenta und Museum Fridericianum, 2012.

Berlin, Isaiah. “On the Pursuit of the Ideal,” The New York Review of Books. 35.4. 1988.

Castells, Manuel. The Rise of the Network Society. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2000.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2006.

Galloway, Alexander. “Networks.” Critical Terms for Media Studies. W.J.T Mitchell and Mark Hansen, University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Lanier, Jaron. “ONE HALF A MANIFESTO.” Edge.org, 11 Nov. 2000. Web. 1 Nov. 2013. <http://www.edge.org/conversation/one-half-a-manifesto>.

Lovink, Geert. Networks Without a Cause: A Critique of Social Media. Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2011.

Moretti, Franco. Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History. London: Verso, 2005.

Verwoert, Jan. “Exhaustion an Exuberance.” Tell Me What You Want, What You Really, Really Want. Sternberg Press, 2010.

Weizenbaum, Joseph. Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgement to Calculation. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman, 1976.

Wiener, Norbert. Cybernetics; Or, Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. New York: M.I.T., 1961.

Footnotes:

1I owe credit to the artist Adam Kaplan, who coined the concept of the Count Syndrome. adamkaplan.net

2Perhaps comparable to Weizenbaum’s “drunkard’s search syndrome” (130).<http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/if_all_you_have_is_a_hammer,_everything_looks_like_a_nail>

3“All code operations (…) come down to absolutely local string manipulations and that is, I am afraid, to signifiers of voltage difference.” Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter (Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1999), 15.

4Permeating much of his work over the past decade, it has found its most thorough articulation in his 2004 publication: Alexander R. Galloway, Protocol: How Control Exists after Decentralization (Cambridge, MA: MIT), 2004.

5 Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), Internet Protocol (IP), Domain Name System (DNS), User Datagram Protocols (UDP), and Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) structure the dominant uses of the Internet.

The post Boot Camp: Count von Counterprotocol appeared first on &.

]]>The post Probe: Instituting Errors: Glitch Imagery in Communications Networks appeared first on &.

]]>Gliché is a free iPhone app that promises to “distort your photos into works of digital art.”1 As characterized in a recent network-based arts biennial that featured the piece of software, it is “a free photo app to generate wrong.”2 The app adopts the aesthetics of glitches—those unanticipated and unintended technological errors—in the service of controlled, deliberate image-production.

Such glitched imagery represents an aesthetic (and set of computational processes) that has lent to sensibilities of a diverse range of cultural producers that includes artists, designers, hackers and software developers. This probe asks how glitch imagery has been used in both artistic and commercial capacities, and what to do with claims of the glitch’s radical nature.

“The break of a flow within technology (the noise artifact) generates a void which is not only a lack of meaning. It also forces the audience to move away from the traditional discourse around a particular technology and to ask questions about its meaning. Through this void, artists can critique digital media and spectators can be forced to recognize the inherent politics behind the codes of digital media”

(Rosa Menkman 340).

In visualizing technological failures, glitches (and similar ‘faults’ within digital systems—i.e. bugs, jams, noise…) compel a view past the controlled surface of the digital. Critical glitches may offer counterpoints to technological systems that rely on efficiency, accuracy and predictability. To standards of streamlined, regimented digital aesthetics, they may represent a more human-scaled information presence; to the problem of plenitude, they may enact a slowing-down or freezing of the cyberflow; to the tyranny of digital logic, they may offer absurdities outside its narrow peripheries. In their most radical instances, glitches may present transgressive modes of cultural and political engagement.

In distinction from more expressly activist strategies (seen in hacking and cracking, culture-jamming, tactical media and cyberfeminist practices) the critical glitch enacts a process of defamiliarization that thrusts “information without a purpose” onto the clean surface of the digital image (Nunes 13). It engenders a heritage of hacking that turns around the tools of a technological system to rupture itself. Here—in the digital realm—a communications system built for the transfer of clear signals is stymied by objects that are corrupted, scattered and mutated. Like Lisa Samuels and Jerry McGann propose of the deformative, deliberate misreading of literature, glitches “short circuit” conventional protocols of reading (30). These are media objects squarelyat odds with those supported by mainstream channels ofdigital circulation, and they warrant a challenge to dominant interpretive frameworks.

Within the history of communications technology, noise represents a deficit in efficient transmission. Forefathers of information theory (and harbingers of contemporary communications networks) Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver sought in the mid-20th-century to diminish noise—to send signals with “zero probability of error” (Shannon 8). This cybernetic ambition was concerned with exacting total programmatic control of information through the eradication of errors. In optimized cybernetic systems, glitches are permitted only insofar as they provide feedback for how best to sidestep them. Thus have contemporary digital communication networks maintained a glitch-free ethos that media theorist Mark Nunes describes as stemming from “a cybernetic ideology driven by dreams of an error-free world of 100 percent efficiency, accuracy, and predictability” (3).

Glitches carry excess meaning onto the digital image’s clean, superficial surface, and thrust into visibility information that is not clear, predictable, or controllable. This noise denotes a communicative malfunction: a disconnect between sender and receiver. Representing a break within its flow of information, glitches may thus offer a critical counterpoint to technologies that rely on efficiency, accuracy and predictability. Where digital technologies necessitate particular protocols of codified interaction, the critical glitch represents an unwillingness to nourish a control system in which legible feedback is crucial. They work against the predictable grain of the digital to offer up “unintended trajectories” (Nunes 8). This unexpected behaviour is the ontology of the glitch: as Cinema scholar Hugh Manon and artist Daniel Temkin describe “one triggers a glitch; one does not create a glitch.”

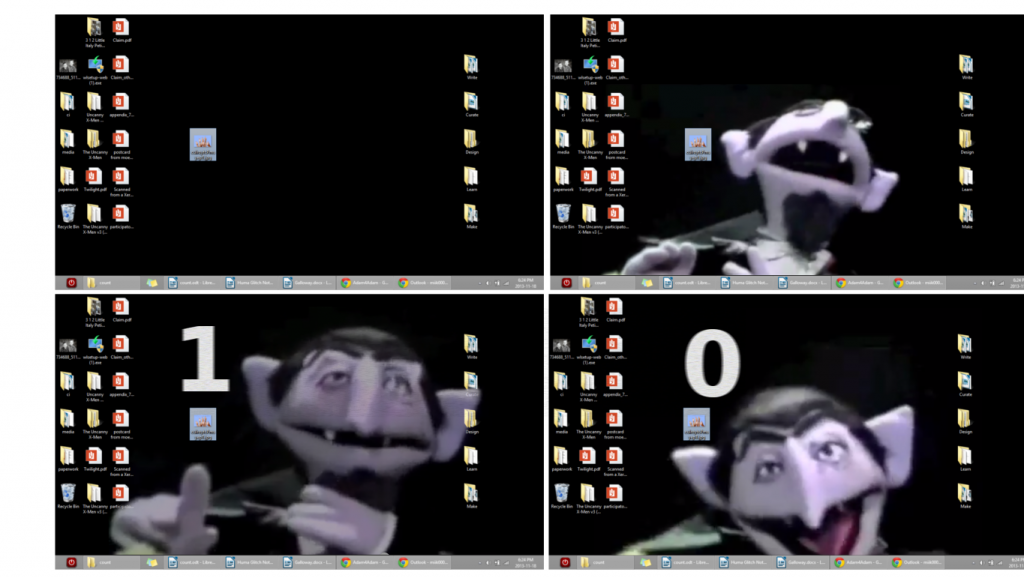

Rob Sheridan. The Social Network Soundtrack by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, 2010

Kunihiko Morinaga’s 2011-12 A/W collection for fashion house Anrealage

Still from Nabil Elderkin’s music video for “Welcome to Heartbreak” by Kanye West

“Errors come in many kinds, but increasingly, our errors arrive prepackaged” (Mark Nunes 13).

“When the glitch becomes domesticated, controlled by a tool, or technology (a human craft), it has lost its enchantment and has become predictable. It is no longer a break from a flow within a technology, or a method to open up the political discourse, but instead a form of cultivation” (Menkman 342).

Given the unpredictable nature of the critical glitch, what are we to do with the predictable, manageable glitch imagery offered by mainstream practices and services like Gliché? Such stylized, superficial glitches seem to fit squarely within the same economic logic of commerce culture media-forms, and of the pixel-perfect, efficient-signal logic of cybernetics. Artist Rosa Menkman warns of a state of “conservative glitch art,” that, as with now-institutionalized Avant-garde art and punk music, capitalizes and neutralizes the glitch (342). As electronic musician Kim Cascone has recognized, we are entrenched in a “famous for fifteen megabytes culture” in which the glitch “is a tactic of subversion that has become a fashion statement” (qtd. in Moradi 19). This prevalence of glitch-like formal design—from high-fashion to popular music production—can be shown to recuperate and defang the critical glitch, mirroring a force that, as Peter Bürger famously wrote of art institutions, “neutralizes the political content of the individual work” (Bürger 90). Here, glitches may be merely cultivated fuck-ups—happy-accidents bred for commercial results. “There is no question,” Manon and Temkin assert, “that the glitch aesthetic [has] been co-opted by mainstream media.”

Indeed, commercial markets have supported a taste for what Italian media theorist Vito Campanelli calls “disturbed aesthetic experiences” (154). Here, “flaws” of digital media are written into commercial objects, taking advantage of the fact that noise, interference, pixilation, etc. have “become part of everyday aesthetic experiences” (ibid.). Hence, synthetic or staged glitches have found their way into popular cinema (from Hollywood to Dogme 95), and into professionally-made ‘amateur’ porn. These objects, Campanelli argues, “attempt to take possession of the truth of the flaw,” benefiting from an aesthetic of imperfection that appears more ‘authentic’ within a context of over-produced, polished media (164). This phenomenon, he suggests, has arisen “in concert with generalized distrust of the cold perfection of the cultural industry as whole.” (Campanelli 166).

This taste for low-fi, crude imagery (and its processes of improvisation, low-skill manipulation, and technical transparency) has further been bred into more vernacular visual sensibilities of the digital age. As internet theorist Geert Lovink has written, “The cinéma-vérité generation’s wish for the camera as ‘stilo‘ has come true: the billions are scratching away with abandon” (11). From digital image filters that increase film-grain and nostalgia (Instagram, etc.), to videos released by hacker group Anonymous, errors in digital media are being extensively exploited by amateur image-makers. These perfected, controlled glitches (or glitch-like) images may thwart the radical potential aspired to by Menkman and her fellow glitch artists.

Do deliberate glitch-making endeavours like Gliché fulfil a kind of conservative, cybernetic imperative—recuperating errors into a mainstream logic of control and predictability? Here, error is parsed as not a way-out, but (as a corrective feedback) a means to underscore the dominancy of the system from which the error arises. Indeed, such deviations could allow for the perfecting of a system’s order and logic. As Nunes relates, “Error, as captured, predictable deviation serves order through feedback and systematic control” (12).

Conceivably, such discrepancy between ‘pure’ and ‘staged’ glitches may be a trivial argument to begin with. Though a glitched file is emphatically deranged, no irrevocable damage is committed in this apparent iconoclasm. As Manon and Temkin argue, “for all the destructiveness in glitch art, it is actually simulated dirt, simulated breakage, simulated risk.” With a low-stake capacity to ‘undo,’ glitch-making at any level does not, as Virilio speaks of uprisings, “penetrate the machine, explode it from the inside, dismantle the system to appropriate it” (74, mentioned by Manon and Tempkin).

Pipilotti Rist, Still from Selbstlos im Lavabad, 1994. Video installation.

Tony (Ant) Scott, GLITCH #12 – IT’S ALWAYS SCHOOL HOLIDAYS ABOVE THE CLOUDS. 2003. Digital image.

Max Capacity, Section Z Glitch, 2010. Still from hacked NES game.

Rather than dismantling technological systems, glitches—as visual, communicative objects—partake in an unbalancing of representational systems in the digital age. At their most radical, they do not demolish the communications networks from which they are born, but engage those networks to perform what Rita Raley calls a “micropolitics of disruption” (1). Thus has the glitch been employed by artists to figuratively rip apart, say, conventions for representing the (female) body (Pipliotti Rist), to render broken the personal computer (Ant Scott), and to restructure protocols for participating with digital systems (Max Capacity), while leaving actual bodies and machines intact.

Such critical, artistic uses of the glitch ask us to attend to our relationship with technology, but no less do the surfaces of some controlled, designed glitches compel a renewed view of technology. These images too may harbour the useless, textural noise at odds with digital logic’s penchant for efficiency and predictability. In their “failure to communicate,” as Nunes conveys, both staged and critical glitches signal “a path of escape from the predictable confines of informatic control: an opening, a virtuality, a poiesis” (3).

Works Cited:

Bürger, Peter (1974). Theorie der Avantgarde. Suhrkamp Verlag. English translation (University of Minnesota Press) 1984.

Campanelli, Vito. Web Aesthetics: How Digital Media Affect Culture and Society. Rotterdam: NAi, 2010.

Lovink, Geert, and Rachel Somers Miles, eds. Video Vortex Reader II: Moving Images Beyond YouTube. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011.

Manon, Hugh S., and Daniel Temkin. “Notes on Glitch.” World Picture 06 (Winter 2011). Web. 15 Jan. 2012. <http://www.worldpicturejournal.com/WP_6/Manon.html>.

Menkman, Rosa. “Glitch Studies Manifesto.” Video Vortex Reader II: Moving Images Beyond YouTube. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011. 336-47

Moradi, Iman. Glitch: Designing Imperfection. New York: Mark Batty, 2009.

Nunes, Mark. Error: Glitch, Noise, and Jam in New Media Cultures. New York: Continuum, 2011.

Raley, Rita. Tactical Media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2009.

Samuels, Lisa, and Jerome McGann. “Deformance and Interpretation.” New Literary History 30.1 (1999): 25–56.

Shannon, Claude. “The Zero Error Capacity of a Noisy Channel.” Institute of Radio Engineers, Transactions on Information Theory IT-2 (September 1956).

Virilio, Paul. The Accident of Art. Semiotext(e): New York, 2005

1 Writes its designer: “Glitché is a free iPhone application to distort your photos into works of digital art using several effects based on computer errors and bugs such as glitch, slitscan, datamosh and many other” <http://cargocollective.com/shreyder/Glitche-2013>.

http://glitche.com/. App designed by Vladimir Shreyder and developed by Boris Golonev and Ivan Shornikov.

Automated glitch-art generators aren’t particularly new, with forerunners like Data Glitch 2, a commercial plug-in for mainstream motion-graphics software, freeware glitch image maker Monglot, and online, real-time generators such as the canvas-API Glitchy3bitDither, animated .gif glitcher YouGlitch, javascript Glitch Images and Imageglitcher, and the iPhone app Satromizer. Gliché has received much critical attention, as indicated in the app’s Facebook photo-stream.

The post Probe: Instituting Errors: Glitch Imagery in Communications Networks appeared first on &.

]]>The post Boot Camp: Mapping National Narratives appeared first on &.

]]>“Широкий” (wide). Gosudarstvenny Gimn Rossiyskoy Federatsii. Russia: 17,098,242 km2

“Wide.” O Canada. Canada: 9,984,670 km2

“Colosso” (colossus). Hino Nacional Brasileiro. Brazil: 8,514,877 km2

“Boundless” Advance Australia Fair. Australia: 7,692,024 km2

“жерім” (vast). Meniñ Qazaqstanım. Kazakhstan: 2,724,900 km2

“Madambo” (broad). Mulungu dalitsa Malaŵi. Malawi: 118,484 km2

The six words in the image above—each pulled from a national anthem—are sized relative to the land area respective to six countries. Thus, Wide (of O Canada‘s “far and wide”) is proportionate to the 9,984,670 km2 within our territorial borders, relative to Kazakhstan’s жерім (vast) 2,724,900 km2. All of these words mean, more or less, big. And through mapping these various national claims at magnitude, apropos their actual territorial size, we may hazard to learn something of the relation between national identity, territorial occupation, and abstraction of the natural landscape.

This map measures spatial relations, not diagrammed continuously in reference to other geological forms, but through a reduced set of relations from a chosen set of countries. For each word, I have redistributed measurements of the country’s total area into black lettering printed in regular sans-serif typeface Ariel. It disregards a mapping tradition based on a certain logical abstraction of the globe—rendered on a flat plane to articulate geometries of proportion and distance—and offers instead a minimized scalar logic of relative territorial sizes weighed against the rather macho, national claims of breadth and girth.

Aside from the most widespread of words in national anthems (which include “our,” we,” and “God”1 )common tropes of national anthems include patriotism, triumph, heroism, and pride; bondage, sacrifice and service; sovereignty, liberty or freedom; victory or struggle—both through war and bloodshed; references to flags and guns; and most commonly: territory. Such boastful size claims as the six I’ve chosen are commonplace in national anthems.

Here, the symbolic assertions of a nation’s magnitude may be mapped proportionate to territorial borders—those delineative bastions of an empire’s material limits. National borders may manifest visibly on the landscape in checkpoints, barricades, walls, ditches, or moats: what philosopher Edward Casey calls their Salient Edges. These are the “unambiguous” boundaries that find representation in cartography, each a “kind of edge that announces itself as an edge.” (Casey, 92).

Such mapping denies fully those ambiguous and imperceptible Subtle Edges found in the natural landscape that lead to embodied, subjective knowledge of a place. The Salient Edges delineating mapped territories are impermeable and constant—artificial impositions that mark an imagined landscape-as-space: a resource, apportionable and profitable. Within its regular edges might we discern myopic, virtualized representations of real places—transfigured into icons of territorial domains. These images of power give way to a conceptualization of the natural world that makes possible its exploitation for economic production. This process is characterized by a disregard for the natural world in a myopia that Casey has called “the hegemony of space over place” (105).

National anthems commit a similar depreciation of place. In reifying the natural landscape within the triumphant myths of nation-states, these songs render the landscape as resource. This is manifest in Panama’s “fertile land of Columbus” (mundo feraz de Colón), Paraguay’s “Magnificent Eden of riches” (de riquezas: magnífico Edén), and Malawi—“Fertile and brave and free” (La chonde ndi ufulu).

In juxtaposing the symbolic claims of a nation-state with an abstraction of its territorial claim, this exercise attempts to give insight into both the use of language in nationalism, and processes of conceptualizing place and space. If the exercise is successful, it is for the degree to which these boastful claims are exposed as contingent upon national narrative and land exploitation. Though perhaps lacking the utility of conventional maps, it visualizes a relationship between places and their official mythologies.

1“Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ).”Nationalanthems.info. Ed. David Kendall. Web. 24 Oct. 2013.

Works Referenced

Casey, Edward S. “The Edge(s) of Landscape: A Study in Liminology.” The Place of Landscape: Concepts, Contexts, Studies. Ed. Jeff Malpas. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2011. 91-110.

United Nations. Demographic Yearbook—Table 3: Population by sex, rate of population increase, surface area and density (PDF). United Nations Statistics Division. 2010.

<http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/dyb/dyb2009-2010/Table03.pdf>

The post Boot Camp: Mapping National Narratives appeared first on &.

]]>The post Cyberflâneurie as a Non-Hermeneutic Research Methodology for Networked Imagery appeared first on &.

]]>“Since the world is evolving towards a frenzied state of affairs, we have to take a frenzied view of it.”

Jean Baudrillard (151)

For the better part of three years I’ve been interpreting digital images.1 Imagery made and circulated on the Web, in my study of the visual culture of network aesthetics, was subjected to my tool-set as an art historian.

In interpreting media circulated on posting boards (like 4chan and 9gag), chat-services, and among artists engaged in Pro Surfing Club culture, I turned my critical attention toward the textures of glitched surfaces, the lineaments of digital artifacts, and the semiotics of remixed media objects. Having had several months to reflect since the completion of my MA thesis, and now having this course to spar my thinking, I’ve come to realize (what likely should be obvious): such interpretive practices do little to articulate the constant stream of content in the cyberflow.

This ‘probe’ chances a critical reorientation to networked media that downplays the interpretive methods chronic to the art historian. Today, with far more data than can be comprehended, (let alone interpreted) the imperative may be to develop new modes of organizing and making sense of the deluge of dataflow worldwide.2 The limitations of interpretive discourses in conventional art historical methodologies are palpable, and require a rethinking of the models used to make sense of the new imagery being developed in digital systems.

A new model could stress the participatory, circulatory frameworks of this imagery, rather than one based on a hermeneutics of its surfaces. It may turn to existing image-making sensibilities to identify the processes engaged during production of the vernacular imagery of internet culture. Such imagery (from viral, spreadable media to common ‘profile-pics’) are always already entangled in larger networks of signification outside any critical focus a researcher may choose to impart. i.e. It would be unfitting to develop lolcat analyses or a hermeneutics of the dick-pic—a grammatology of animated gifs or a taxonomy of selfies.

This approach would concentrate less on the specificity of meaningful surfaces, and more on the matrix of possibilities (technical, sensual, epistemological) that characterizes the networked environment from which they are born: less an emphasis on interpretation, and more on the production and circulation of the media artifacts themselves. Instead of analyzing the surface of an image, rich ideas may come from asking how the image can come into being to begin with, how it comes to be recognizable and sharable as an object, and how and why it circulates within a network. Such questions thrust into view the social and technical elements on which systems of image-circulation rely.

Such a perspective gains steam from the work of literary theorist Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht. He argues that a focus on materiality or structure should replace the orthodox emphasis on interpretation in the study of cultural artifacts. “Interpretation,” he charges, has “become the predominant… paradigm that Western culture [has historically] made available for those who wanted to think the relationship of humans to their world” (Production of Presence 28). With an imperative to abandon interpretive methods, Gumbrecht advocates a recourse to nonhermeneutic methodologies (such as writing—Schrift), endeavouring for a focus on the production of presence—that is, on the tangible, material aspects of communication. Such methods better illuminate the conditions on which the emergence of meaning is possible to begin with.

By dropping my dedication to interpretation within my study of digital media, I might better discern the ‘exterior’ properties of “Materialities of [digital] Communication,” which allow these images to emerge (Materialities of Communication 389). I might cut through the low-fi, low-brow surfaces of the imagery in question to reveal some of its primary functions. In a study of digital media, this perspective could carry one “from higher to lower levels of observation” where all digital artifacts may be reduced to mere binary signals, or voltage difference as Friedrich Kittler tell us (150). Further, the approach may reveal the modes by which images and ideas are developed and shared within digital networks. They may, as Dilip Gaonkar and Elizabeth Povinelli propose for reading new cultural forms, “foreground the social life of the form rather than reading social life off of it” (387, emphasis in original).

Jon Rafman

promotional image for Kool-Aid Man in Second Life, ongoing

Second Life avatar, performative tours, videos

Existing artistic practices may serve as a beta model for new research methodologies concerning digital images. These practices are situated to move within the protean stream of the dataflow—surfing (we might add surfen to Gumbrecht’s schrift) through digital media objects, while avoiding the pitfalls of bestowing them meaning.

Enter the cyberflâneur.3

They are what Geert Lovink has called data dandies, and Vito Campanelli: Travellers in the Aesthetic Matrix: networked wanderers – spontaneously archiving as they surf through the media landscape.4 Notably, elaborate practices of cyberflâneurie have been developed in Artist Surfing Clubs—small leagues of artists engaged in a blog-like public exchange of found and remixed digital media.

544 x 378, ComputersClub, DoubleHappiness, Loshadka, NastyNets, SpiritSurfers, and Supercentral are among the first and most famed clubs, each of which assembled between 2005 and 2010. Microcosms of the networked media environment, these are elastic, collaborative research-creation groups bent face-first into the global communications network. Their products are dense vortexes of media that suck in a wide breadth of digital forms to transfigure and transpose their objects within a public arena. Sampled, slashed and remixed, this imagery manifests from a vantage deeply entrenched within a culture of everyday life online.

doublehappiness.ilikenicethings.com_slash_question_p=1502. 2010.

Digital image from Nasty Nets Surfing Club.

The cyberflâneur’s is a methodology of navigating the media commons that participates directly in its erratic flow. Counter to a process of interpretation, it is more akin to Susan Sontag’s erotics—a more concrete and sensual mode of engaging one’s object of study.5 Their embodied method sheds light on the processes by which content is produced online by generating images as inscriptions within their networks of engagement

This ‘probe’ proposes that the cyberflâneurie visible in Artist Surfing Clubs represents an engaged practice best equipped to research and articulate digital images. It aims to turn away from interpretation and meaning, and toward the type of creative engagement espoused by the cyberflâneur. A participatory research methodology that adopts such cyberflâneurie, instead of the hermeneutic distance of the art historian, might allow an intimate, emic knowledge of these media forms.

In embodying the copy-paste sensibilities of the cyberflâneur—in surfing the deluge of networked media—a researcher might better comprehend these objects at the level of their material reality. It is an approach tethered not to interpretive practice, but to the participation in their circulation. Rather than developing a model that obliquely delineates the complex ecology of any single image or system of networked images, a participatory methodology may allow a richer reading that does not reduce the complexity of the thing it describes to mere explanation—to “sequential elements of syntax,” but rather aims for preserving the “infinity of the task,” as Foucault wrote of the inadequate “relation of language to painting” (8, 9).

This effort is not fully without precedence in art historical methodology, as manifest in approaches that emphasize the circulation of art objects, the social histories of art and aesthetic trajectories, and various post-structural modes that stress extralinguistic, contextual, and political dynamics and veer from inherited interpretive methods. Anti-hermenutic positions against the writing and speaking about art are commonplace, as in Sontag’s account of aesthetic interpretation as a “violation” against art (6).

The modes of engaging with digital media objects forged by artist-surfers layout a relational research method unsympathetic to logical reference and interpretation. This much may be obvious, for the imagery in question—often navel-gazing and vapid—does not behoove one to give an analysis on-par with what Velazquez’s Las Meninas elicits (this is the painting Foucault was concerned with). The cyberflâneur’s reading of digital images, though, may best crystallize (punctualize?) the historical present, conveying those fleeting elements of experience that Jonathan Stern recognizes as the absence not recorded in traces of historical documents (80, 81). Participation in these digital networks may directly convey what ordinarily comprises the “lost data” of historicity (84). For engaging in networked media exchange surely reflects the various degrees of boredom, conflict, uncertainty—the lack of continuities, the lapses and excesses of meanings—encountered in any form of image- or knowledge-production online. These practices might help to better articulate that which lies outside of these traces of networked communication—that which goes unseen by the strict protocol of the Web and by the restrictive purview of the art historian.

Art-historical and art-interpretive skills may come up short when applied to networked media objects—the primary content of which is located not on the surface of any individual image, but rather in what they are composed of and how they move within networks. A horizon of comprehension narrowed by a research method that demands rational interpretation would misread the Net’s diarrhetic procession of images as merely referential forms. In not subjecting this imagery to interpretation, we might conceive of their composition as fluid and circular, rather than fixed and chronological (as my skills as an art historian had prepared me to do).

To understand the selfie, the social-media meme or the pirated video, in short, necessitates participating in its circulation. Cyberflâneurie, as a performative research methodology, characterizes digital imagery as immanently material and circulatory, and enables a cleared view of “all those phenomena and conditions that contribute to the production of meaning, without being meaning themselves” (Gumbrecht, Materialities 8). The unlikely practices developed in Artist Surfing Clubs may here represent an alternative research method for comprehending digital imagery. It allows one to deal simultaneously with the surfaces of emergent images created in networked spaces, and the unstable relations between those components that make up the network.

Notes

1 And I’m thrilled to mention myself in a footnote for the first time: Mikhel Proulx. The Progress of Ambiguity: Uncertain Imagery in Digital Culture. Thesis. Concordia University. 2013.

2 The worldwide amount of data produced in the “digital universe” in 2012 alone was 2.8 zettabytes (2.8 trillion gigabytes). John Gantz and David Reinsel, “The Digital Universe in 2020: Big Data, Bigger Digital Shadows, and Biggest Growth in the Far East,” International Data Corporation and EMC Corporation (December 2012).

3 The term emerged, surprisingly, in a 1998 essay in Ceramics Today which touted new, transient forms of operating in cyberspace. Steven Goldate, “The ‘Cyberflâneur’ – Spaces and Places on the Internet,” Ceramics Today (1998).

4 Geert Lovink, “The Media Gesture Of Data Dandyism,” CTheory.net (1 Jan. 1993); Vito Campanelli. Web Aesthetics: How Digital Media Affect Culture and Society. Rotterdam: NAi, 2010. Chapter IV.

5 She ends Against Interpretation with the polemic: “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art” (7).

Sources

Baudrillard, Jean. Impossible Exchange. London: VERSO, 2001. Print.

Campanelli, Vito. Web Aesthetics: How Digital Media Affect Culture and Society. Rotterdam: NAi, 2010. Print.

Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Pantheon, 1971. Print.

Gantz, John, and David Reinsel. “The Digital Universe in 2020: Big Data, Bigger Digital Shadows, and Biggest Growth in the Far East.” Published by International Data Corporation (IDC), Sponsored by EMC Corporation, Dec. 2012. Web. <http://www.emc.com/collateral/analyst-reports/idc-the-digital-universe-in-2020.pdf>.

Gaonkar, Dilip Parameshwar, and Elizabeth A. Povinelli. “Technologies of Public Forms: Circulation, Transfiguration, Recognition.” Popular Culture 15.3 (2003); 385-97.

Goldate, Steven. “The ‘Cyberflâneur’ – Spaces and Places on the Internet.” Ceramics Today (1998).

Gumbrecht, Hans Ulrich. “A Farewell to Interpretation.” Gumbrecht, Hans Ulrich, and Karl Ludwig Pfeiffer, eds. Materialiries of Communication. Writing Science. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1994. 389-402. Print.

–. Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004. Print.

Kittler, Friedrich. “There Is No Software.” C-Theory.net. Arthur and Marilouise Kroker, Eds. (18 Oct. 1995). Web. <http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=74>.

Lovink, Geert. “The Media Gesture Of Data Dandyism.” CTheory.net. Arthur and Marilouise Kroker, Eds. (1 Jan. 1993). Web. <http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=136>.

Proulx, Mikhel. The Progress of Ambiguity: Uncertain Imagery in Digital Culture. Thesis. Concordia University. 2013.

Sontag, Susan. Against Interpretation. London: Vintage, 1994. Print.

Sterne, Jonathan. “Rearranging the Files: On Interpretation in Media History.” The Communication Review 13:1 (2010): 75-87.

The post Cyberflâneurie as a Non-Hermeneutic Research Methodology for Networked Imagery appeared first on &.

]]>