The post Boot camp: (In)Corporations of Fairy Tales in ABC’s Once Upon A Time appeared first on &.

]]>Moretti argues there is at least one “consequence of [the network model] approach: once you make a network of a play, you stop working on the play proper, and work on a model instead: you reduce the text to characters and interactions, abstract them from everything else, and this process of reduction and abstraction makes the model obviously much less than the original object” (4), leading me to wonder whether there’s value in the network model approach in folklore studies; is the network model appropriate for exploring and ideally illustrating the use of a fairy tale character despite and/or because of its specific placement in plot? What are the potential benefits of seeing folklore from a network perspective than from, say, the database of the ATU? For my boot camp, I decided to explore the potential of network diagrams with Once Upon A Time, which is of particular interest because of its constant allusions to Disney fairy tale films, and the dense network of fairy tale themes this move invokes.

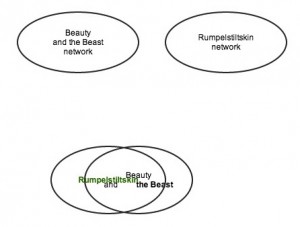

In my first diagram, I attempted a simple and somewhat failed attempt to illustrate how Once Upon A Time combines two previously independent networks, or tales (fig. 1) – in this case, the previously independent tales of “Rumpelstiltskin” and “Beauty and the Beast.” However, this diagram only indicates that two tales overlap, and provides no supplementary qualifications for this relationship. After experimentation, I ended up with a Venn diagram to represent my network (fig. 2). This Venn diagram attempts, like Moretti, to “make visible specific ‘regions’ within the plot as a whole; subsystems, that share some significant property” (4). Venn diagrams comparatively evaluate data, which I use to demonstrate the “regions” of plot (that of “Rumpelstiltskin” and “Beauty and the Beast”) ABC constructs in Once Upon A Time’s narrative by sharing significant tale attributes (e.g. character associations).

Thus “Rumpelstiltskin” is also the Beast from “Beauty and the Beast.” But this narrative is further complicated with ABC’s explicit allusions to Disney’s version of Beauty, Belle, who shares the same name and attire as ABC’s live action version; “Rumpelstiltskin,” “Beauty and the Beast,” and Once Upon A Time collapse into each other under the umbrella corporation of Disney, owners of ABC since 1996. This Venn diagram ends up illustrating Disney’s corporate ownership of specific tale attributes (Belle) and ABC’s consequent (legal/legitimate) ability to manipulate Disney associations, simultaneously enacting folklore’s transformative gestures as well as corporatized indications of self-reference that actually paradoxically close off the network of folkloric associations in favour of expanding economic investment. In the densest part of the Venn diagram, we have the most convoluted manipulations of the folklore network for the consolidation of corporate ownership through cable network television.

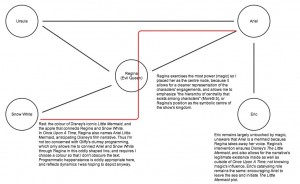

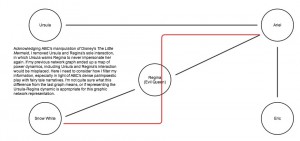

This almost hegemonic assimilation of two or more tales continues and becomes a hallmark trope of Once Upon A Time. My third through fifth diagrams examine “Ariel,” the episode dedicated to “The Little Mermaid,” which unsurprisingly emulates the Disney version by referencing Ursula (unknown to the tale-type prior to Disney), Ariel (once again, Disney specific), and clothing the titular character in the same attire Disney created over a decade ago. In fact, “Ariel” is fascinating precisely because ABC capitalizes on Disney’s copyright ownership and elaborates upon The Little Mermaid while enabling its narrative: while Prince Eric appears in the episode, his knowledge of Ariel is minimal and can actually inform the movie’s catalyzing romantic plot;

prior to Regina’s (the Evil Queen from “Snow White”) impersonation of Ursula, Ariel believes Ursula is only a myth, and thus ostensibly would not have sought the sea witch out in the film if not for the knowledge Once Upon A Time imparts upon her; Regina actually names Ariel Little Mermaid, becoming ABC’s narrative consolidation as well as corporate nod to their parent company. Thus Regina is the centre node of my network diagram, because her character not only fuels the narrative with her machinations, but visually marks the centripetal structure of the corporate networks at work.

“No interaction is crucial in itself. But taken together, they perform an essential reconnaissance function: they make sure that the nodes in this region are still communicating: because, with hundreds of characters, the disaggregation of the network is always a possibility” (Moretti 9). This is where suspicion informs my plotting of ABC and Disney networks: no interaction is crucial, but as the removal of Regina makes clear, the Evil Queen’s interactions are in fact crucial to legitimizing the combination of Snow White, the Little Mermaid, and even more tales in Once Upon A Time. The enforcement of Disney’s network through self-references legitimizes these fairy tales as Disney’s property, and “with hundreds of characters, the disaggregation of the network is always a possibility.” Thus, we have the Evil Queen, a tyrannical monarch who colonizes various tales under Disney(‘s)World, a self-enclosed narrative where transformations are only variations of their own copyrighted characters, and the transmission and transmutation of tales have shifted from the public sphere to the privatized corporate one. As much as my first diagram attempted to illustrate two previously closed-off networks opening affiliative possibilities, what my diagrams have made visibly evident is that these networks seem to have become increasingly more (in)corporated.

Works Cited

“Ariel.” Once Upon A Time. ABC. 3 Nov. 2013. Television.

Moretti, Franco. “Network Theory, Plot Analysis.” Literary Lab 2 (May 2011).

The post Boot camp: (In)Corporations of Fairy Tales in ABC’s Once Upon A Time appeared first on &.

]]>The post BorderLands: (Para)Textuality in Cartography appeared first on &.

]]>“[A]rt, as we have seen, is being edged off the map. It has often been accorded a cosmetic rather than a central role in cartographic communication. Even philosophers of visual communication… have tended to categorize maps as a type of congruent diagram – as analogs, models, or ‘equivalents’ creating a similitude of reality – and, in essence, different from art or painting. A ‘scientific’ cartography (so it was believed) would be untainted by social factors. Even today many cartographers are puzzled by the suggestion that political and sociological theory could throw light on their practices.”

– J.B. Harley “Deconstructing the Map” (4)

Where does the map lie in the image (fig. 1)? Despite cartography’s objective, locational confusion already occurs when considering maps’ framing practices. I am interested in how “cartography” engages with “illustration,” and whether the two are separable enough to say cartography and illustrations are two distinctly different elements of the map proper; in the complex network between illustration, style, data and image, when and where is the map (as a text), and when and where is it distinguished from that which surrounds it (the paratext, the extra-textual)? How do a map’s elements identify and orient place? When Harley argues that “[r]ather than being inconsequential marginalia, the emblems in cartouches and decorative titlepages can be regarded as basic to the way maps convey their cultural meaning” (9), he notes the mediation of “extra-” or paratextual information as part of evaluating a given text (the map). Consider Google’s Maps Engine Lite, a program that highlights the process of mapmaking (fig. 2): drawing, stylizing and layering (i.e., filtering and framing data) determine the map program – because the computer algorithmically processes the mathematical and scientific geographical data, the program’s creative capacity is defined by framing mechanisms that make obvious discursive filters in cartographic processes.

So how separable are paratext, context and text in mapping practice? To separate and omit the (re)presentational elements of a map from cartographic study is to make the same mistake that Kate Trumpener isolates in Moretti’s “Style, Inc. Reflections on Seven Thousand Titles (British Novels, 1740-1850),” where Moretti’s omissions of certain subtitles in his survey – or the framing mechanisms used to present or map information – “foreclose analysis of the relational assignment of generic designations as part of a mutually constitutive genre system” (163). I, following Harley and Trumpener, would like to address the “generic designations” of illustration and map in cartography, to see how information is appointed in a “mutually constitut[ed] genre system,” how generic expectations inform the production and reception of maps. Harley wants to deconstruct the map, reveal the “attempt[…] to purge [mapmaking] of ambiguity and alternative possibility” (10), but his biggest limitation is that he does not acknowledge the rich history of cartography’s exchanges between paratext, context and text.

How do generic expectations inform the production and reception of maps? This question depends on context. Gerardus Mercator’s Atlas Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura (1569) endorsed a “scientifically rigorous worldview” arising from Mercator’s mathematically inclined geographic projections which “mapped the continents to the same accurate scales for the very first time” (Beauty of Maps). While Harley’s cartographic model has been the prevailing one for centuries, the “correct relational model of terrain” (4) was not always the reigning and framing rhetoric of cartography. In the medieval mappamundi (fig. 3),

“[t]he world [is] presented somewhat summarily, [and] stands in for the variety of its contents, monsters, and all…. [T]he map shows not only the physical earth, but also its spiritual history” (Edson 505). Thus Jerusalem lies in the center of Hereford’s Mappamundi, and the rest of the world emerges from this theological locus, while Christ observes from above and judgment day occurs at the top of the mappamundi, outside the globe’s sphere. Theology, politics and even empire visually and conceptually shape the map, with unknown territories marked by monstrous others like the Blemyes (fig. 4),

headless humanoids with eyes in their chests, or the Sciapods, a race of desert-dwellers who use their sole overgrown foot as a sunshade (fig. 5). Cultural capital is the locus of this map, and the mappamundi’s schema is directly determined by medieval beliefs, where there is less familiarity and easy affiliation the further from Jerusalem one moves on the map; the more removed one is from English medieval culture, the further the subject matter is pushed towards the data’s terminal and the stranger the creatures one encounters.

Thomas de Wesselow argues “[t]he tremendous visual disarray of the map is a sign of man’s fallen vision of the world. In a way it directs attention away from the world, away from trying to understand the world, towards trying to achieve an understanding of, a vision of, things outside the world, of heavenly things” (Beauty of Maps). The map enforces an ideological ideal as its framing mechanism, and the medieval traveler accordingly orients themselves within the discursive matrix of the mappamundi.

Richard Macksey and Michael Sprinkler define paratexts as “those liminal devices and conventions, both within and outside the book, that form part of the complex mediation between book, author, publisher, and reader” (i), a definition coupled with the book that I would like to extend to maps and mapmaking for the purpose of this probe. Does context or paratext mediate the map, or is a map simply a “mirror of nature” (Rorty qtd. in Harley 4)? If paratextual information mediates the reader’s reception of the book, medieval cartography also mediates its contemporaneous observers’ relation to the medieval world (and even a contemporary observer’s relation to the medieval world is telling: removed from the post-Enlightenment ideal of scientifically accurate information, we are puzzled, unable to enter and navigate the mappamundi’s cosmos. Without discourse as our legend, orientation is difficult). Another way of asking “which image constitutes the map” is asking “what is paratext and what is text” in the map-as-object; which relations shift in the cartographic network of representation? In the case of the Hereford mappamundi, what is “paratextual” – illustrations, legends, dedications – is actually contextual, and by medieval cartographic standards, it becomes simultaneously textual since mappaemundi, and the Hereford Mappamundi in particular, discursively as well as geographically situate – they are not just spatial, but temporal (eternity is embedded around the globe, separating celestial and terrestrial [fig. 6]), theological (Christianity), and cultural (imperialism, the unknown Other).

Fig. 6 The four thongs connecting the world to the surrounding sphere spell MORS, Latin for “death.”

Grayson Perry’s Map of an Englishman extends and makes explicit the merging of paratext, context and text (fig. 7).

Perry’s map of an Englishman’s consciousness does not match the physical object to its cartographic representation, and the mapped text (the mind), the paratext (the images and representational politics) and context (auto/biography and/or culture) mutually inform each other. Perry enforces awareness of discursive filtering, graph(t)ing into his map the “consciousness” of Enlightenment ideals: “[g]ood method creates a reliable representational conduit from reality to depiction. It is a one-way street. Nature is made to speak for itself” (Law 7). But as Law points out, this is a “sleight of hand … because realities are being made alongside representations of realities” (7), alongside Perry’s own tongue-in-cheek portrayal of these dynamics. Thus schizophrenia, anorexia nervosa, agoraphobia, hypochondria, psychopath, bipolar disorder and more litter the map’s oceans, where the ejection of these official pathologies from the mapped landscape of consciousness shapes the Englishman’s mental geography, creating the conditions of subjectivity by establishing borders which restrict consciousness and consequently what that consciousness can constitute. In typical deconstructive binary fashion, ideology enforces what should not be and defines what is. Perry’s map illustrates its awareness of “which realities” it has chosen, the “political” and “crucial question” of discursively filtering (cartographic) mess (Law 7), of the fact that “maps contain less information about a territory than about the way it is observed and described” (Siegert 13), the way it is culturally inculcated. In the case of Perry’s Map of an Englishman, cartography tells us less about the Englishman at hand: regret, photo-album, instinct, matriarch, gossip, etc., are not unpopular life experiences or isolated to any specific Englishman. Instead, Perry’s map illustrates the data a subject organizes and evaluates when orienting themselves in the confluence and excess of signifiers. The emphasis in Perry’s map lies in the title’s indefinite article. Mapping here reveals an ordering of the undetermined and underdetermined, that which needs to be plotted in order to be expressed.

The conditions of mapping are isolated in Harvey’s “Deconstructing the Map” to geographic cartography, but as Arthur Jay Klinghoffer notes, “mapping is a schema that may be applied to the brain, genome, emotions, literature or cyberspace in addition to continents, mountains, and coastlines” (1). An awareness of the rhetoric, in Harvey’s words, or the “fingerprint of history” in Moretti’s (97), and the discourses enacted in cartography can provide significant opportunities for critical examination of how ideology endorses and shapes cartography, its referent, and the subjects orienting themselves within these dynamics. For example, Google presents its maps as positivist signifiers of world geography, a catalogue of photographs that need not skew mathematical representation due to massive amounts of digital data. In Google Maps, the transcendental subject subtends the map, rather than Perry’s indeterminate one: finding a place in the Google Maps mobile app requires the user type in the address they wish to find from “My location”; Google Maps preserves your home, work, and any other locations deemed important enough to record (here, discursive authority even designates documentation) (fig. 8);

Google Maps orients location and subjectivity by visually centering the traveler on the screen. If theology guides medieval mappaemundi, the (independent and/or transcendent) subject guides current digital mapping technologies, regulating geography through simulated point-of-view shots that emphasize the subject as cartographic center. We seem to have entered a Barthesian writerly map, into a landscape that plots the subject as “no longer a consumer, but a producer of the text” (Barthes 4), establishing the parameters for a personalized map (albeit ones very different from Grayson Perry’s). However, Google Maps is actually a large-scale accumulation of photographic data, which is “to be read, but not written: the readerly” (Barthes 4). Locations are entered, and the traveler’s presence is even confirmed via GPS in the case of mobile technologies. But the data is already in place before present orientation is specified, so can the subject really shape the map in this digital cartography? For Harley, “the map has attempted to purge itself of ambiguity and alternative possibility. Accuracy and austerity of design are now the talismans of authority culminating in our own age with computer mapping” (10). Google Maps assumes an egalitarian cartography influenced by the Enlightenment presumption of objective positioning, but it merely transfers the Author-God function from the medieval God and theological discursive authority to the digital map’s excessive Enlightenment fervour for accuracy to the point of photorealism. A map is meant to authoritatively orient, and this orientation undeniably goes beyond geographic. So must we always be discursively positioned in maps? Harley deconstructs the map, but is is there a deconstructive map that plots or instigates aporia rather than authority? Should cartography be more transparent in its cultural operations? To frame the question differently, where does cartography’s use and value lie – in its locational applications, its geographical representation, its discursive topology, etc.?

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. S/Z: An Essay. Trans. Richard Miller. New York: Hill and Wang, 1974.

The Beauty of Maps. Dir. Steven Clarke. BBC. November 2011.

Edson, Evelyn. “The Medieval World View: Contemplating the Mappamundi.” History Compass 86 (2010): 503-517.

Harley, J.B. “Deconstructing the Map.” Cartographica 26.3 (Summer 1989): 1-20.

Klinghoffer, Arthur Jay. The Power of Projections: How Maps Reflect Global Politics and History. Westport: Praeger, 2006.

Law, John. “Making a Mess with Method.” Lancaster: The Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University, 2003.

Macksey, Richard and Michael Sprinkler. Preface. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Trans. Jane E. Lewin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Moretti, Franco. “Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstracft Models for Literary History – 2.” New Left Review 26 (March – April 2004): 79-103.

Siegert, Bernhard. “The Map Is the Territory.” Radical Philosophy 169 (September/October 2011): 13-16.

Trumpener, Kate. “Paratext and Genre System: A Response to Franco Moretti.” Critical Inquiry 36.1 (Autumn 2009): 159-171.

The post BorderLands: (Para)Textuality in Cartography appeared first on &.

]]>The post “Reality is not made of statements,” But Stories Are. appeared first on &.

]]>In his analysis of paraphrase, Harman argues that “[t]here is no reason to think that any philosophical statement has an inherently closer relationship with reality than its opposite, since reality is not made of statements” (14). Fairy tales make obvious Harman’s warning that metaphysical and ontological realities are not made of or reducible to statements: tellingly removed from the “real” and defined by Stith Thompson as “tale[s] of some length involving a succession of motifs or episodes… [and] mov[ing] in an unreal world without definite locality or definite characters and filled with the marvelous” (8), fairy tales are a subset of the folktale antithetical to nature or reality, to an object as it simply is in a realm of Platonic ideals. In “The Inherent Stupidity of All Content” (11-14), Harman is clearly interested in statements regarding reality (specifically, the relation between Lovecraft’s statements and comprehensible ontological representation), but fairy tales present the exact opposite relation to realism; rather than the typical reception of statements vis à vis the truth, fairy tales make explicit that they do not speak for the world we inhabit. Fairy tales, märchen, or contes des fées are cultural objects whose very names point to the fact that they cannot make any claims to ontological or phenomenological reality, and as such I believe they can be valuable objects to explore Harman’s interest in the politics of experiencing and/or representing an object.

The fairy tale, then, does not attempt to explicate or delineate reality so much as to escape it, and despite being a massive break from Harman’s ontological and literary interest in Lovecraft’s writings, folklore nevertheless exemplifies Harman’s phenomenological gap, most obviously the “horizontal gap,” or what he describes as “the cubist gap between an accessible object and its gratuitous amassing of numerous palpable surfaces” (31). Individual utterances of a specific tale are what define the largely and historically oral tradition of folklore. Each tale’s variant, whether it be that of words or narrative details, becomes the cubist flag flapping in the wind (Harman 30), and his argument that “what we end up with are the truly pivotal qualities of the thing” in Lovecraft’s literary style and phenomenological perspective are exactly the methodologies inherent in folklore studies (31), which typically examines a particular folktale given its various and varying iterations across – and consequent incorporations into – time and space (i.e., its periodization and nationalization, its material distribution via literary and oral renditions in public and private spaces, etc.). In fact, János Honti proposed in 1939 that the fairytale is “a kind of cookie-cutter Platonic form or model which manifested itself through multiple existence [sic]” (qtd. in Dundes 195). This seems remarkably similar to Harman’s example of the flag as an ontological object, where “the specific qualities of the flag encountered at any given moment do not hide the flag as a unitary object, but exist as something extra, encrusted on its surface” and ostensibly expendable in our conception of the object (30; emphasis added). Honti’s notion that a tale-type is a cohesive object with varying manifestations results in the same gap between the accessible object (in this case, the folktale) and its “gratuitous amassing of numerous palpable surfaces” (Harman 30), and moreover informs the classification process of folkloric indexes, which attribute specific iterations of stories to a larger archetypal narrative of the folktale in question. What becomes tautological in Harman’s philosophically inclined argumentation is in fact folklore’s modus operandi. One significant distinction arises: to continue with Harman’s rhetoric, folklorists use each cubist surface or tale’s point of entry for juxtaposition; repetition is not tautological here, but structural, allowing folklorists to recognize specific instances of a larger archetypal tale structure. So while for Harman the “banality” of statements has grave consequences for philosophical theses (14), what his article frames as an issue of discursive relativism (reality is not made of statements) is actually what allows folklorists to identify a tale’s integral constituents, and propose some reality regarding a fairy tale’s identity. In other words, iterations’ variations (within Harman’s argument, a paraphrased statement) reveal an archetypal structure that defines a particular tale and what can be categorized as such a tale, proposing some reality-value regarding a story’s identity rather than revealing, as Harman and Zizek argue paraphrase does, a statement’s removal from reality.

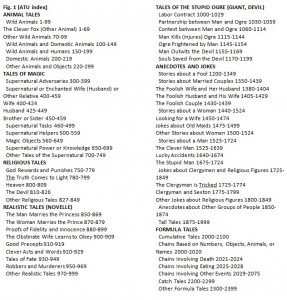

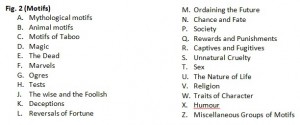

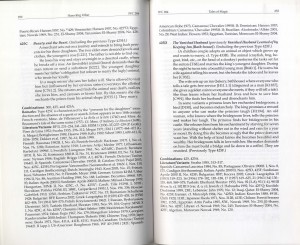

So I began with the premise that the fairy tale genre repudiates reality, and yet have concluded that it still makes a truth claim. In fact, Antti Aarne (1910), Stith Thompson (1928, 1961), and later Hans-Jörg Uther (2004), have created a classification system (herein abbreviated to ATU index, tale type, etc.), which is widely acknowledged as an invaluable source in folklore, “an international sine qua non among bona fide folklorists” and authority on what constitutes a specific tale (Dundes 195). In the ATU index, a folk tale is given a code based on numbers and letters. The number corresponds to types of tales, and the letter to tale motifs (see figs. 1 and 2).

Thus “Beauty and the Beast” is ATU 425C (fig. 3), introducing the motif of taboo (in the particular case of 425C, the Beauty figure “overstays the allotted time” when visiting her family [Uther et. al 252], resulting in the Beast figure’s near demise) to the Search for the Lost Husband tale type. This is distinguished from its mythological predecessor, “Cupid and Psyche,” which is typically identified as straddling 425A (“The Animal as Bridegroom”) and 425 B (“Son of the Witch”). This organization inevitably raises questions: why is “Beauty and the Beast” identified as 425C, whose ATU motif assignment deals with taboo, when “The Animal as Bridegroom” seems to be the larger focus of the tale? When it comes to the ATU index, framing mechanisms emphasize the object as somehow transcendent, yet the mechanism itself is highly mediated.

Perhaps some awareness is necessary of how, as Foucault warns us, “divisions[,]” in this case those between tale types, “are always themselves reflexive categories, principles of classification, normative rules and institutionalized types; they are, in turn, facts of discourse which merit analysis alongside other facts, which certainly have complex relations with them, but do not have intrinsic characteristics that are autonomous and universally recognizable” (303). But the problem can be exceedingly complex, especially when such awareness makes evident just how political categorization can be. For example, is “Cupid and Psyche” 425A, 425B, or should it have its own category? What influences the process of categorization (hint: in the overall category of ATU 425, Search for the Lost Husband, ideologically encoded language and titling which denies female agency and emphasizes patriarchal roles), and what are the limits of these boundaries and their impacts? What does choosing one motif over another as the vital motif imply? If “Beauty and the Beast” is in fact determined by the taboo of Beauty “[breaking] the prohibition of staying home too long” (Thompson et. al 252), the sociopolitical implications of a tale defined by a woman failing to return to the beast who possesses her due to a failed transaction (specifically, her father’s failed transaction with the Beast) is certainly telling. In fact, even the Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales argues that “[u]nlike the Cupid and Psyche tale… where the emphasis is on the breaking of the taboo that forbids the young woman to look at her husband… ‘Beauty and the Beast’ emphasizes the animal qualities of the groom and his ultimate transformation from a monster into a human being” (106), and yet it is still identified under the “taboo” motif.

Here is where Harman’s “vertical gap” occurs, the one “between unknowable objects and their tangible qualities” (31). A fairy tale is language, words spoken out of mouths or script read on a page. Their tangibility is undeniable, but their categorization, the knowledge of what any specific tale is, remains less certain. Organized by tale type and subcategorized by motif, the ATU index highlights folklore as a medium of repetition, paraphrase and slight transformation. Thus no story will remain identical to its previous iteration, and the very notion of a tale independent from its type confuses and befuddles when considering folklore from within the context of the ATU indexical system. Is “Beauty and the Beast” a distinct tale type, where each iteration or variant is a single unit or cubist facet of its expression, or is it a less certain and more troubling distinction between tales that are, by ATU tale-type definition, different and inherently so? In the instance of ATU classification, a tale’s tangible qualities, a specific variant’s pronunciations, names, regional references, diction, cultural mores, etc. often reveal gaps between what can be known (the tale I have accessed) and the “unknowable object” (Harman 31), or the tale type as a consistent unit or ontological object. However, while I establish a connection between the ATU index and Harman’s ontological “‘vertical’ gap,” it is important to note that Harman’s gap is due to the evasion of signification, whereas the ATU index’s “vertical gap” is due more to an excess of signifiers, of diegetic elements and narrative motifs that expand potential forms of categorization rather than completely evade them. And this is where and how discourse emerges in the ATU indexical system: with an excess of signifiers, discourse becomes the inevitable filter for the database.

Having reached the end of my probe, I realize I have argued that fairy tales are antithetical to reality, make truth-claims regarding a certain kind of reality (regarding the stability of an archetypal tale and the collusive politics of categorizing, naming and consolidating narrative details), and are ultimately undermined by this gesture due to excessive potential signifiers and consequent discursive moderation. And so I, like Lovecraft, find I am unable to directly talk about a thing, and instead must move about it and probe it from different angles while ultimately unable to coalesce these details. Folklore is, like Lovecraft’s writing, “disturbingly alert to the background that eludes the determinacy of every utterance, to the point that [both] invest[…] a great deal of energy in undercutting [their] own statements” (Harman 28). However, I’m comforted by the fact that folklore also struggles with this, and that its rich history of mining tales for traces and motifs that can help identify a story have increasingly battled with the dissatisfaction over motivated categorizations. As Harman argues, “objects are what the classical tradition called substantial forms, inhabiting a mezzanine level of the cosmos, and can be paraphrased neither as a meaning for some observer nor as the dangling product of some genetic-environmental backstory” (253). The ATU index attempts to both identify a “genetic-environmental backstory” (the archetype) as well as provide meaning (“Beauty and the Beast,” according to ATU classification and prioritization, is a story about a woman who fails to return to her husband, as opposed to a story about a woman who becomes an expendable transaction being forced to return to her place of imprisonment). Fairy tales are by definition fiction, but what about their forms of classification? Is an archetype a fact, or a convenient, if not necessary, fiction? Should the methodologies and scholarly paradigms used to study a fairy tale correct their relationship with reality, or emulate what they examine? Is this a matter of preference, or an ethical issue, given the seeming customary (and increasingly moreso) coupling of folklore and ideology? So while Harman argues that “we can only support objects” (253), I would like to emphasize that we must first examine those objects’ relations to us, and in cases like folklore we must also question whether something is (easily) determinable as a cohesive object, and evaluate whether Harman’s phenomenological gaps à la Lovecraft produce valuable complications of just how “we produce our own real objects in the midst of [perception and context]” and the knowledge bases these productions secure (260).

Works Cited

Ashliman, D.L., ed. “Beauty and the Beast: Folktales of Type 425C.” Folktexts: A library of folktales, folklore, fairy tales, and mythology. University of Pittsburgh, 25 June 2009. Web.

Dundes, Alan. “The Motif-Index and the Tale Type Index: A Critique.” Journal of Folklore Research 34.3 (Sep. – Dec. 1997): 195-202.

Foucault, Michel. Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology. Ed. James D. Faubion. Trans. Robert Hurly et. al. New York: The Press, 1998.

Harman, Graham. Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy. Washington: Zero Books, 2011.

Swain, Virginia E. “Beauty and the Beast.” The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales. Volume 1: A-F. Ed. Donald Haase. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2008 ed.

Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1946.

Uther, Hans-Jörg. The types of international folktales: A classification and bibliography, based on the system of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2004.

The post “Reality is not made of statements,” But Stories Are. appeared first on &.

]]>