The post Musical Trees appeared first on &.

]]>Boot Camp – November 7

The German-Swiss poet Hermann Hesse once wrote, “Trees are sanctuaries. Whoever knows how to speak to them, whoever knows how to listen to them, can learn the truth. They do not preach learning and precepts, they preach, undeterred by particulars, the ancient law of life.”

I have always had a great appreciation and fascination for trees. As a child, my favourite thing to do was explore the “Fairy Glen” in Scotland, listening for the fairies hiding in the trees and waiting to hear or see some form of life within the forest. My love for trees and their powers led me to name my most recent musical project “Tree Talk” . For this week’s boot camp I decided to make a tree diagram from a collection of Newfoundland and Labrador Fiddle Tunes by Newfoundland musician Kelly Russell.

His collection took place between 1970-1980 with Canada Council funding. Russell concentrated his collecting on the west coast of Newfoundland and Labrador because he knew there were many fiddlers living on the West of Newfoundland and Labrador. He makes note in the introduction that he does not claim to have visited every fiddler, but he believes his collection is an accurate representation of the music being played in these areas at that particular time.

Most fiddlers were between 50-70 years old, and many passed away before the publication of the book (2003). He would show up to towns and ask, “Does anyone around here play the fiddle?” Being a well-known personality gave Russell easy access and welcomed attitudes in each new town and village he visited.

He believes that there was once a broader musical tradition that has died out in most areas of Newfoundland and Labrador, and feels as if his collection documents the last remains of this tradition. The difficulty in tracing sources of tunes was a challenge, and Russell is unaware of many sources of tunes he collected, as were the players themselves. Many also did not know the names of tunes they played, which resulted in titles printed in the book such as “Old Reel #3.”

Mapping out this collection could have gone in many directions. Did I want to visualize the amount of tunes from a particular region? Or perhaps specify the particular types of tunes found in each region? Did I want to focus on the individual fiddlers and their contributions to the collection? Or the keys that the tunes were played in? I drew my tree diagram to first show the six geographic areas Russell collected from, and then broke it down into the different fiddlers from those regions, and finally to the amount of tunes they contributed to the collection by type of tune (reel, jig, waltz, etc.).

Another factor making this collection difficult to graph is the fact that many fiddlers played the same tunes, but he only published them once under one fiddler. It is not specified which other fiddlers shared the same tunes, so the most popular ones are not noted. If one were graphing the music by geographical region, the data would not be accurate due to the lack of specificity of players and tunes. Depicting the shared tunes in a tree diagram would be a wonderful method of showing the interweaving of tunes from one place or person to another.

Moretti says, “A tree can be viewed as a simplified description of a matrix of distances,” and that they are “a way of sketching how far a certain language has moved from another one, or from their common point of origin” (46). I would propose taking Russell’s collection further and finding the original rooting places of fiddle tunes and tracing how they moved geographically from one place to another over time. Simply tracing what was being played at one point in time in particular areas is an interesting snapshot, but the interesting data behind it would be very useful information. Plotting out this tree diagram resulted in me having more questions rather than feelings of satisfaction.

I have drawn on a blank map of Newfoundland and Labrador the six areas Russell collected from, and indicated the number of tunes published from each region. Seeing the actual geographic space each region takes up on a map makes me realize how much of the province he did not collect from, and how varied the areas are in size and location. For example, he collected fifty tunes from the tiny area of Stephenville/St. George, but only forty tunes from Labrador, which is massive in comparison. Russell collected from four fiddlers in both of those regions, but is there a reason that the repertoire is larger in Stephenville/St. George than in Labrador?

Just for fun, I graphed the number of tunes by geographic location, matching the colours from my map and tree diagram. NL graph

I thoroughly enjoyed this week’s boot camp and readings, and being able to critically examine this collection, which has been a major part of my musical life. I hope to take the investigation further and to find answers to some of my many unanswered questions.

Works Cited

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History – 3.” New Left Review 28 (Jul-Aug 2004): 43-63. Print.

Russell, Kelly. “Kelly Russell’s Collection: The Fiddle Music of Newfoundland & Labrador, Volume 2, All The Rest.” Trinity, Newfoundland: Pigeon Inlet Productions Ltd, 2003. Print.

The post Musical Trees appeared first on &.

]]>The post bootcamp: “ ”, the Bellman cried! appeared first on &.

]]>

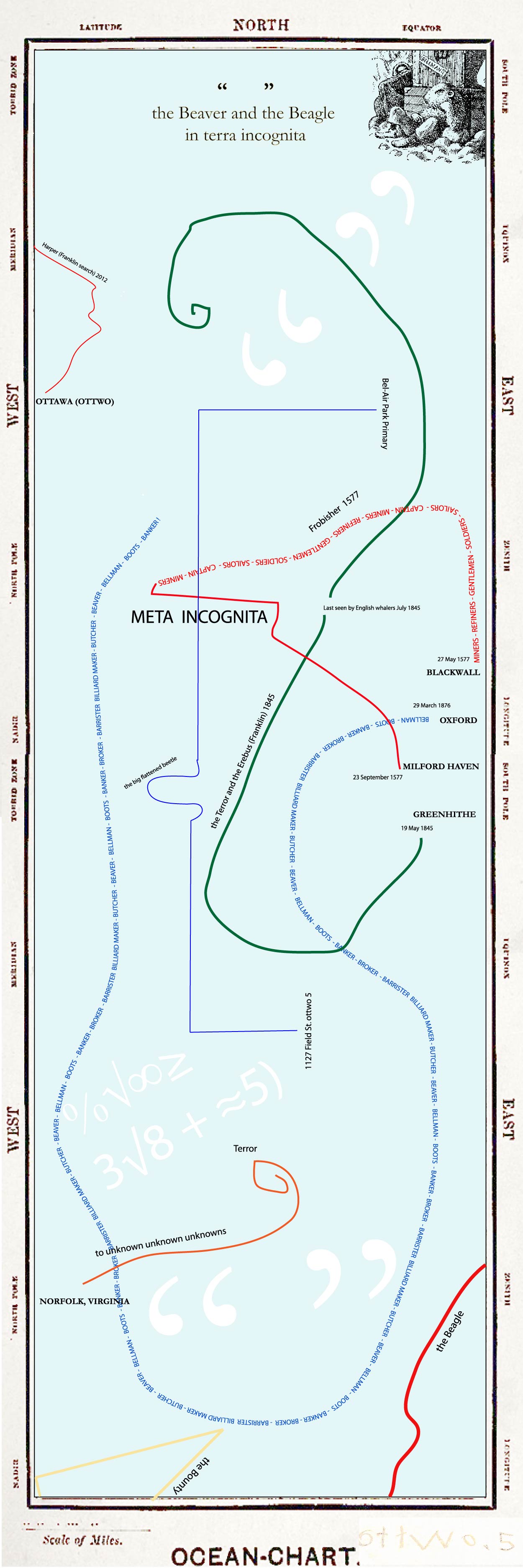

The Beaver and the Beagle in terra incognita.

This map is a continuation of my look at The Hunting of the Snark (1874) started in the Markdown boot camp. A narrative is a kind of a map, a map of a journey through time. So The Hunting is already a map or a certain kind–a map with a certain end (a jovial evasion of oblivion by a logician). And it also contains within it a literal (blank) map as a clue, or a decoy or an amusement. My new map makes a layering of one narrative on top of another to add cross-dimension to the linearity of narrative. This allows me to situate some juxtapositions without asserting them as fact in an expository way. The layering here begins with thinking about the terra incognita (unknown land) to which the Bellman’s map seems to refer, those blank spaces on the early maps of empire not yet explored or assayed. By Carroll’s C19, the apex of empire, very few of these blanks remained in the space/time of Victorian cartographers. To the map of The Hunting I add a fragment of the journey’s of Martin Frobisher, who searched and mapped Baffin Island on behalf of the English crown. In 1577 he returned to London from Baffin with tons of ore (mistakenly thought to be gold) and three kidnapped Inuit (mistakenly thought to be cannibals). What you desire most comes along with what you fear most (gold with cannibals, snarks with boojums). Queen Elizabeth named the new-claimed territory meta incognita (the unknown limits). To this layer is added trajectory fragments of the Franklin expedition, which departed England in 1845 and became lost (thirty years before The Hunting). Searches for Franklin’s lost ships and men continued sporadically into the 1870’s. Much commercial exploration in the arctic was carried out under this label (and it goes on, witness Harper’s search). To this is added a last layer which is my own pre-literate trajectory through The Hunting by crayon and my first trajectories through my childhood neighborhood.

Is this map accurate to the data? I think not. Does it have an intentional or specific communication goal. No. Are the juxtapositions intentional? Yes. Is the intention for a fixed result or reading on the part of the reader? No. Does it have value as a critical tool? Perhaps. If I am a designer engaged to create a visualization of a certain communicable position I am making a representation of that position or ideology. If I do my job professionally the facts and the ideas (and the ideology) will all line up. If, however, I mimic such a rationalistic representation as a gambit to juxtapose some disparate information, facts, views, conjectures without knowing the specific outcome for individual viewers, then I might be mis-designing with purpose. In this case I have made some choices about what to put in this mix, but without premeditation about what people should conclude. In other words, the juxtaposition comes before the conclusion as a kind of pre-thought. (No doubt conclusions seep in along the way.) So the designer or the social scientist (or the explorer) is looking for things to ‘appear’ as nodes in the data according to the map’s logic. Hunting for the Snark, so to speak. But another question is what might ‘disappear’, sliding into the cracks of this method.

The post bootcamp: “ ”, the Bellman cried! appeared first on &.

]]>The post Bootcamp: Our Humanities Theorists Tree-mapped appeared first on &.

]]>Bootcamp + Trees + Nov 7

“There is a constant branching-out, but the branches also grow together again, wholly or partially, all the time.” – Alfred Kroeber, Anthropology

Experiencing our class thus far, I must say it’s been less painful then expected to get my mind inside the theory circle. Once I became familiar with the ‘big names’ and most of the prevalent terms and ideas, everything became much easier. The circulatory nature of theory in the Humanities is evident as you read repeated names and quotes cited in each of our readings. And, as the semester has worn on, it has already become clear to me who speaks loudest to my sensitivities, my ways of working and my intuition. I have favorites: theorists I’ll keep tabs on and those I probably won’t. It’s the same for them. Some drool over Foucault while other go for Delueze and Guattari.

Franco Moretti had me at ‘graphs’.

This last series of Graphs, Maps, Trees is right up my alley because I am an intensely visual learner and communicator. Moretti gave us darn good reasons as to why this use of quantitative data and its visual representation add something to the textual humanities and can give us a new way of seeing. Of Graphs, Maps, Trees, I’m most interested in Trees. It probably has to do with my subject of study and its long lineage or my penchant for trees themselves. The graphs here feel less rigid, more organic and illustrate the more ‘messy’ bits of quantitative data better. Either way, I knew it was the perfect form for my latest question: the lineage of thought.

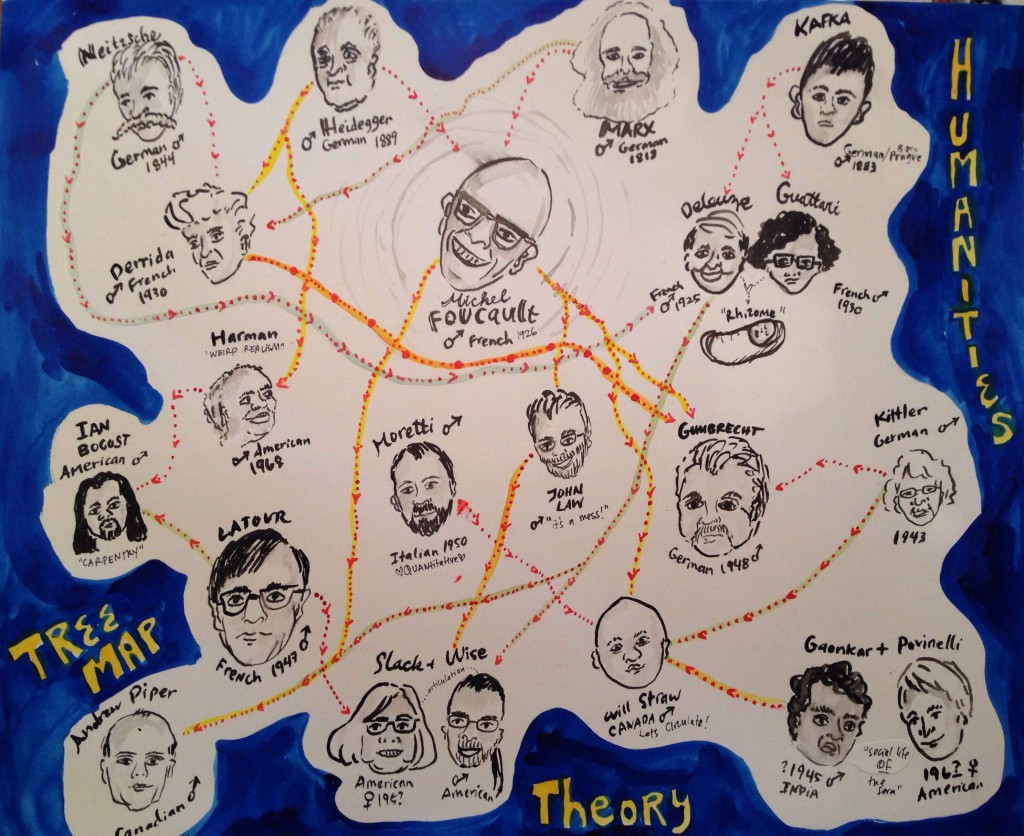

For this week’s Bootcamp, I’d like to experiment with our own syllabus. Who/what are we reading and what did those people read? How is the flow of theory/knowledge passed down to us and how do we become a part of it? Who inspired those who inspire me?

So, I made a tree graph.

I chose to do this with my own artistic interpretation because 1) I’m horrible with computer programs, 2) It’s dead fun to cartoonize the serious theorists we’ve been reading*, 3) We can see how the cartographer’s bias can influence our interpretation of the information. My method was similar to Moretti’s method of plotting Hamlet in next week’s Network article: I went through all of the readings and marked down each writer’s direct positive references within the articles we’ve read. If there was no obvious citation, I went online and did a search to see who their biggest influences were. I, by no means, exhausted these articulations. Sadly, I had to make many omissions and simplifications in order to fit it on the page. JP Harvey’s Deconstructing the Map and its warnings about the cartographer’s inherent bias is well taken.

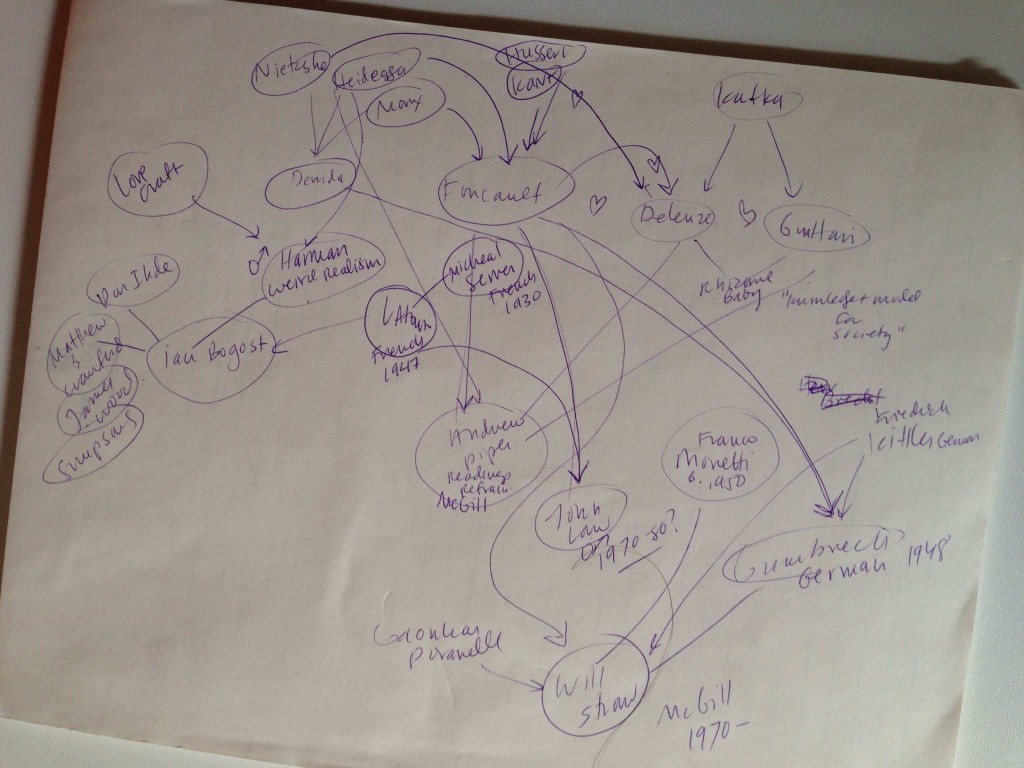

My initial plotting of the theorist tree:

Although it looks like a network graph, it’s really a tree: I loosely placed them from oldest (top of the page) to youngest (bottom of page). And even though it’s messy – it actually does help me see things:

- If you want to be a theorist in the Humanities, you should probably grow a mustache.

- Foucault is by far the most referenced writer in our readings.

- There are other prominent authors that reference within the Humanities less but are referenced more (Moretti, Latour). Does this speak to writing style or more independent or interdisciplinary thought?

- If you do this long enough and are awesome at it, you will come to be referenced by last name only. Also, if you are in collaborative pair.

- Weirdly, there is little symbiotic sharing of intellectual love (other than the collaborative pairs). Most of this seems to simply be because of generational spans.

- At first glance, I thought: of course, it’s all a bunch of white guys from Germany and France. But if you look more closely at the ‘generations’ from top to bottom, you can see that even just in the last 50 years, the field has become much more diverse. I’m not sure if this speaks to the field at large or if Darren has just done a good job of making a point to include these scholars.

To place myself within the spaghetti dinner of thought, I’d probably plop myself down right below Moretti, John Law and Slack and Wise. I feel comfortable there in all directions: Mess, visual representations the present new information to the humanities and Articulations and Assemblages. Interestingly, these scholars are inspired by some of the others that I simply can’t get into – but now, seeing the lineage, feel closer to.

What do you see? Can you see anything at all? Does it help to clarify things or just confuse you? What does humor do to the information? Where are your pathways?

*Making Foucault look like the evil mastermind in the middle was a bit of an accident. Or was it?

And, just for fun, the winning mustache goes to: Nietzsche.

The winning overall hairstyle: Marx.

References:

Goodwin, Jonathan, and John Holbo. Reading Graphs, maps & trees: responses to Franco Moretti. Anderson, SC: Parlor Press, 2011. Print.

Harley, J. B., and Paul Laxton. The new nature of maps: essays in the history of cartography. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. Print.

Moretti, Franco. Graphs, maps, trees: abstract models for a literary history. London: Verso, 2005. Print.

The post Bootcamp: Our Humanities Theorists Tree-mapped appeared first on &.

]]>The post In the Presence of Missing Samples appeared first on &.

]]>Having a freshly generated floor plan of a previously unknown structure is a huge advantage, but if warfighters then have to enter the space, it is very important for them to know of any hazards. The robot must detect objects of tactical significance and annotate such on the map. “When you ask warfighters for a prioritized list of what they want to know about, the number one answer is always human presence,” said [the technical director]. “From a detection standpoint, humans have two obvious characteristics that can be exploited, in that we move around and we give off heat.” […] “The fundamental problem is fairly obvious,” [he continued]. “If the robot is standing still, anything that moves could potentially be a human. But once the robot itself starts to move, everything its sensors ‘see’ appears in motion, and so this simplistic algorithm becomes ineffective.”

This probe aims to investigate one specific mapping technology essential to one of the more horrific events in which we are taking place. The technology is a multifarious one: the Human Presence Detection System, utilized in everything from an iPhone’s face-recognition software to the surveillance drones over Yemen, from urban riot management to the ‘progressive scanning’ of container ships for illegal immigrants hidden among the cargo. As is apparent in the quote which opened the probe, accurate mapping of human presence and activity by robotic sensors has never really been a merely technical hurdle to be overcome by a refining of devices – this sort of mapping is just as complicated by the ontologizing role of observation as was that of the explorer who sketched the nonhuman world. In accounting for the parallax of an HPDS that must move through what it maps, the humans it must locate are more and more thoroughly constituted with a kind of bare subjectivity: in the space between false negative and false positive, which shifts as the tracker tracks, humanity can be found.

In the new mapping regime cartography no longer struggles to find places in which persons can instigate event, but rather persons in which the event can unfold into place. This centrifugal movement in the act of mapping – a fugue-centric line of sight that flees the center – has been announced by both Moretti and Siegert. “Relations among locations [are] more significant than locations as such,” says the one (Moretti 96), because, says the other, “the marks and signs on a map do not refer to an authorial subject but to epistemic orders and their struggles for dominance over other epistemic orders.” (Siegert 11) But these two authors diverge in on a point that I believe our case study can help elucidate. Namely, Moretti’s distinction between a ‘map of mentalité’ and a ‘map of ideology,’ against Siegert’s refusal to distinguish at all between form and content in his redress to a ‘radical hylomorphism.’

In the new mapping regime cartography no longer struggles to find places in which persons can instigate event, but rather persons in which the event can unfold into place. This centrifugal movement in the act of mapping – a fugue-centric line of sight that flees the center – has been announced by both Moretti and Siegert. “Relations among locations [are] more significant than locations as such,” says the one (Moretti 96), because, says the other, “the marks and signs on a map do not refer to an authorial subject but to epistemic orders and their struggles for dominance over other epistemic orders.” (Siegert 11) But these two authors diverge in on a point that I believe our case study can help elucidate. Namely, Moretti’s distinction between a ‘map of mentalité’ and a ‘map of ideology,’ against Siegert’s refusal to distinguish at all between form and content in his redress to a ‘radical hylomorphism.’

Moretti does in fact think a kind of form/content division into his mapping, with a few caveats. On the side of content he places mentalité, “the omnipresent, half-submerged culture of daily routines—position of the fields, local paths, perception of distances, horizon—which […] is often entwined with the performance of material labour.” (Moretti 85) Not only does this quote clearly give emphasis to the worked-matter that content is normally understood to be, it also takes individual human knowing, perception and presence as matter. On the side of form then, “not mentalité, but rather ideology: the worldview of a different [outside] social actor, […] whose movements duplicate the perimeter of […] mentalité, while completely reversing its symbolic associations” (ibid). Before I go on, the first caveat here is that I am putting aside the literary context in which Morreti applies his reading for now. The second caveat is that my reading requires taking his phrasing on page 98 to mean that both ideology and mentalité are present, rather than identical, in each other’s maps. Both are tethered to a ‘world of the mind’ of some sort, but ideological mapping is a second level procedure that depends upon the ‘stuff’ of mentalité for shaping and occurs intersubjectively. “A map of ideology emerging from a map of mentalité, emerging from the material substratum of the physical territory.” (ibid)

Siegert however rejects the idea that there are different modes for the map. He begins with the hylomorphism of Aristotelian philosophy, which held that “the operations that allow the matter to become form are inherent in the structure of the matter; […] form is completely turned into expression,” and he ends with a “media-philosophical conception, [where] each of the two terms, [content and expression], embrace form and matter.” (Siegert 16) In effect this is to say that the temporal relationship between form, matter, content and expression are wholly excised. Unlike Moretti, who acknowledges a physical world prior to our familiarity with it, and a perception of the world prior to the ideological subversion of the range of perceiving – two priorities and two different kinds of responsibility for the mapmaker – Siegert ironically disempowers mapmaking in the same stroke that he makes everything indistinguishably mapped (“there would be no [humanity, race, class, etc.] without cultural techniques”). Siegert’s sense of the new regime “therefore consists of a vehement criticism of an ontological conception of philosophical terms [alongside attempts] at revealing the operative basis of those terms.” (Siegert 15) Fitting that his paper ends with a nod to deterritorialization; what is more emptied of territory than the map made by nonhuman sensors programmed to see only what is human?

Returning to the juxtaposition above of rates of false negatives (no human presence detected, when someone is actually there) against rates of false positives (human presence detected, when nobody is actually there), it should be noted that I lifted this graph from a scholarly paper proposing human motion detection based not on the satisfaction or not of criteria, but purely on anomalous signal variance in a wireless field. Suddenly, wi-fi hotspots are maps updating themselves as your body passes through, connected to them or not. Suddenly, you are neither a posited being nor a host of negated alternatives, but mere anomaly, and thus in need of surveillance. But the range of HPDSs goes on and on, and can be at best gestured towards by a recent survey of the industry, readable here:

http://www.eng.yale.edu/enalab/publications/human_sensing_enalabWIP.pdf

Siegert has said that he does not want to go the route of the cultural studies theorist seeking to understand the map by understanding the intentions of the mapmaker – their particular parsing of an independently existing world. Instead, he is interested by the way that the subjectivity of the mapmaker is founded by their mapping (Siegert 13) and, as on-point as he may be when we look at the anti-hermeneutic opera of human presence detection technologies, I can’t help but feel that something is lost when the map is taken to be entirely a-intentional and commensurate-with-territory. If “the whole question of representation was shifted towards the question of the conditions of representation” (Siegert 15), then the answer is mind-numbingly obvious: the condition is violence – the technique is violence – the relation is a violent inclusion, a symposium, a polishing of the cutting edge in human presence detection. In the more forgiving reading, mapping’s “conditions” can be traded for its “intentions” without much fuss. But in the less forgiving reading it is as if Siegert has confused Moretti’s ‘map of ideology’ for the only sort of map on offer, when in actual fact a truly ideological mapping depends on the possibility of an outside for subversion to take place. Without an outside, a “condition” alterior to that of global capital, we are just dealing with one mentalité among the rest, albeit one that is much broader (imperially vast) than that of a meagre sensor from the provinces. (Moretti 94).

Though the individual may share a condition with instruments of human detection, though it may be mapped alongside strangers, it is its unmediated particularity that throws off the sensors: a humanity closer to balaclava than face.

WORKS CITED

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History – 2″. New Left Review 26 (March/April 2004: 79 – 103

Siegert, Bernhard. “The Map Is The Territory.” Radical Philosophy 169 (September/October 2011): 13 – 16

Dakis, Ann. “Human Presence Detection”. CHIPS: The Department of the Navy’s Information Technology Magazine (October/December 2011) Online ISSN 2154-1779

Teixeira, Thiago. “A Survey of Human-Sensing: Methods for Detecting Presence, Count, Location, Track, and Identity”. http://www.eng.yale.edu/enalab/publications/human_sensing_enalabWIP.pdf

The post In the Presence of Missing Samples appeared first on &.

]]>The post Getting Graphic: Representing Representations in Humanities and Sciences appeared first on &.

]]>Preview:

INTRODUCTION: GOOGLING GRAPHS

A Google search for the prompt “graphs are…” yields the following results: the best way to summarize data, visual representations of what, everywhere, often constructed from tables of information, and what of relationships. These fragmentary results illustrate the various approaches to graphs by different fields of research and institutional practices, as well as common conceptions regarding their purpose and value. In the article “Graphs, Maps, Trees,” Franco Moretti argues for a quantitative approach to illustrating literary trends; a shift from hermeneutic practices around individual texts to a quantitative analysis of literature (67). Introducing graphic displays of literary information exposes the field of literary studies to the questions aforementioned, not only is the question what the display shows but how and why its modality functions and what are the implications regarding power relations. What are the politics of graphing and how do they relate to the respective fields of humanities and sciences? Why does quantitative analysis in literature warrant such a “revolutionary” sentiment?

LITERARY LIKENESS: GRAPHS IN HUMANITIES

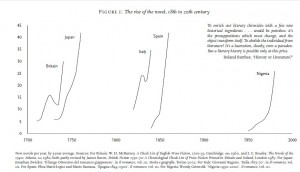

In “Graphs, Maps, Trees” Moretti employs a combination of line and bar graphs to illustrate his empirical analysis of the rise and fall of the novel. “Figure 1: The rise of the novel, 18th to 20th century” depicts increases in literary production in Britain, Japan, Italy, Spain, and Nigeria over 300 years with specific clustering effects (Moretti 69).

Moretti introduces the scholars whose data will provide the basis for the graph at the start of the section two, several lines before referencing Figure 1 in text and a page before the actual illustration (68-69). The contextualization then appears before the reader encounters the graph, and is repeated in the figure caption which also lists the sources, as is captured by Figure 1 above. This reiteration of source material provides an emphasis on validity and traditional scholarly methods, that by referencing accepted scholarly work the author’s own hypothesis or statement is by connection authorized as well. Joseph Bensman discusses the elitism of footnotes whereby one must cite another scholar who is “equal or higher in prestige” in order to gain legitimacy (450), the data sources for Moretti’s graph work similarly. The graph and its data sources connote power relations precluding contradictions and complexities of authorship and authority, as power exerts its forces in humanities research through the figure of the Author-god. Bensman states that “footnotes have important institutional, “political” and aesthetic functions” (443); similarly these functions are also influenced by and through the graphs presented. The aesthetics as well as the political functions assert the graph’s authoritative dominance, Moretti uses a quote from lauded scholar Roland Barthes to champion the removal of the subjective from his analysis and thus this quote corroborates the quantitative analysis methodology (69).

BATTLEDOME: SCIENCE VS. ARTS

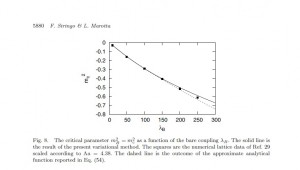

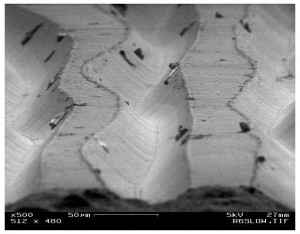

Moretti states that “graphs are not models; they are not simplified versions of a theoretical structure in the way maps and (especially) evolutionary trees” are (72): graphs are relations. Moretti both supports and contradicts this thesis with his own graphs; although they do illustrate relations between the numbers of books produced and the books’ locations, the accuracy as well as the reliance on traditional scholarly validation subverts the radical claims. Cosma Shalizi criticizes Moretti’s methods, arguing that Moretti should have analysed the data himself and mathematically calculated the probabilities for clustering occurrences and errors (118). This argument represents the burgeoning issue of transplanting quantitative analysis methods from science based research to literary practices. If Moretti’s data sources are proven wrong, or if his methods are found faulty then his argument for literary quantitative analysis can be refuted. An example of traditional scientific graphs is found in Figure 2, taken from a scholarly paper on Higgs modelling, a scientific phenomena which, as the paper attempts to prove, can be adequately imagined through specific microscopic structures called crystal lattices (Siringo 5880).

Regardless of its scientific meaning, the graph connotes several key statements which illustrate the shortcomings and successes of Moretti’s quantitative analysis. The line graph uses the caption to describe the phenomena and its graphic representation, it does not refer to outside sources for validity of previous results. Secondly, error is factored into the illustration by the size of the data points as well as the predicted function (the dashed line). By encrypting the graph with secondary information that is accessible through the primary study, the scientific graph elucidates the conceptualization process, turning to transparency for validation and allowing the reader to deduce its value rather than relying purely on precedent research.

Yet the scientific graph reinforces power relations by assuming the reader is adhering to the conventions of reading graphs, for example understanding that larger data points mean more possible error. Audience influences the output, the graph and caption describe sets of social relations and systems, discursive sets in a Foucaultian sense. In Andrew Piper’s article “Reading’s Refrain: From Bibliography to Topology” he suggests literary topology, which analyses the text not through hermeneutics but by assigning values to the lexicographic elements and represents them visually, signals an inspection of places in which literature intersects with other types of social strata and discursive readings (394). The inability to escape power relations through graphs, both in the humanities and sciences, highlights the connection between the process of academic research, Authorship (as in the panoptic) and social rules. Moretti hypothesizes that “quantification poses the problem… and form offers the solution” (86) which can be compared to concept of literary topology. Literary topology, as Piper illustrates in the Goethe graph, performs a similar function to work of Moretti’s graph, preferring quantitative data to the interpretative techniques (385), exhibiting shifting power relations between Author and reader that allow the reader more authority. This also is present in the scientific article, as form is contextualized later in the Higgs paper, when the discussion reveals the equation for the line graph and its derivation, evoking specific associations to fields of study and popularized theories. Therefore the graph summarizes the data while reflecting the environment in which it was constructed, physically from the digital program which produces the equation to the politics of theory behind the illustration.

HYBRIDIZATION STATION

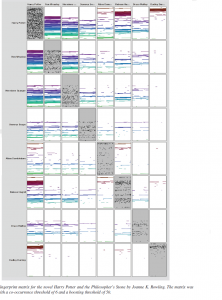

Moretti’s graph attempts to convey more than one set of data results, i.e. more than one line segment. The results represent a comparison between countries and publication numbers, yet temporally they do not provide a cohesive linearity and further inference on the part of the reader is required. The article “Fingerprint Matrices: Uncovering the dynamics of social networks in prose literature” examines inter-character relations and compares these relations between novels, such as The Queen’s Tiara by Carl Jonas Love Almquist and J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philospher’s Stone. Although the articles’ subject matter is slightly different, both propagate quantitative analysis of relations as the main analytic form; the graphs included illustrate the shift in methodologies and as such Piper’s concept that topology is the analysis of ratio rather than difference (379).

“Fingerprint Matrices” presents material in a radically different graphic form than in the Moretti article, it uses matrix graphs to visual social networks. Ratio is “knowledge of the relational and the scalar, the co-presence of difference” (Piper 382); this is witnessed in the Harry Potter matrix graph which highlights the relationships between characters as well as their placement within the novel and subsequently their importance in the plot. With multiple goals the graphing structures must change as the two dimensional line graph used by Moretti is no longer able to display the information, and thus fingerprint matrices (as seen in Figure 3) are created instead (Oelke 372), becoming visualizations of text.

Alongside the fingerprint matrices are the researcher’s methodologies and background sections. The latter section (which cites Moretti) again displays the typical academic posturing, however it is more concise than previous essays examined. The methodologies section describes data collection, processing and graphic output, something which is markedly absent from Moretti’s section two-Figure 1 relationship. Piper states “when we read topologically we are reading our way through language’s historical entanglements,” (Piper 378) therefore the fingerprint matrices not only examine the repetition of Harry Potter characters, but the changes in research illustrations and performs a conjoining of theory and criticism (Piper 389). By producing a methodology whereby all its mechanisms become pellucid the validity of traditional research in humanities changes. No longer do the citations hold substantial authoritative power, but the empirical data and its representations are available for the reader to evaluate the efficacy of the results. Therefore the modifications of the mechanism and its display alter the researcher’s writing as well as the traditional outline of literary articles, which now use methodology and discussion section headings.

Conversely, the opposite argument can be made, that the articles modify the methods; these texts are located in digital domains. All three graphs outputs are digitally rendered, the scientific graph and fingerprint matrices both disclose the graphing procedures which use programs to sift and organize data. By analyzing the pixilation of the lines and the familiar settings of LaTEX, Moretti’s graphappe ars to be constructed via computer program. Digital graphs now require the reader to examine new elements, such as the efficiency of graphing programs or the image resolution in order to discern veracity and value. A further discursive set creates the authoritative relations between journals and readers, another power relation that highlights the function of graphs in scholarship. Currently these articles are available online through Science Direct and the Arts and Humanities Databases, which limits use to university affiliations yet still disseminates the material to a larger audience than through paper production. As quantitative analysis opens more possible readings to literature, the ‘entanglements’ of objects grow; the graphs emphasize the rules of literary production and character relations, rather than the meaning and the objects themselves, reflecting the increased multiplicity of articles and journals available. This perhaps addresses Piper’s question “what does it mean to read electronically?” (373); digital reading utilizes electronic resources and thus makes conscious our academic practices of reading in humanities research. Ultimately more questions remain, those still left unanswered include: how do these academic objects move through popular culture? Where are the intersections between fields of research in regards to graphing techniques? Does digital production of methods alter the function of research?

Works Cited

Bensman, Joseph. “The Aesthetics and Politics of Footnoting.” International Journal of Culture, Politics, and Society 1.3 (1988): 443-470. Web.

Munroe, Randall. “Tall Infographics.” XKCD.com. October 4, 2013. Web. October 19, 2013.

Moretti, Franco. “Graphs, Maps, Trees.” New Left Review 24 (Nov-Dec 2003): 67-913 Web.

Oelke, D., D. Kokkinakis and D.A. Keim. “Fingerprint Matrices: Uncovering the dynamics of social networks in prose literature.” Eurographics Conference on Visualization 32.3. Ed. B. Preim, P. Rheingans and H. Theisel. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2013. Web.

Piper, Andrew. “Reading’s Refrain: From Bibliography to Topology.” English Literary History 80 (2013): 373-399. Web.

Shalizi, Cosma. “Graphs, Trees, Materialism, Fishing.” Reading Graphs, Map, Trees: Responses to Franco Moretti. Ed. Jonathan Goodwin and John Holbo. Anderson: Parlor Press, 2011. 115-139. Web.

Siringo, Fabio and Luca Marotta. “Nonperturbative Effective Model for the Higgs Sector of the Standard Model.” International Journal of Modern Physics A 25.32 (2010): 5865-5884. Web.

The post Getting Graphic: Representing Representations in Humanities and Sciences appeared first on &.

]]>The post Probe: Phonographs, Maps, Carpentrees appeared first on &.

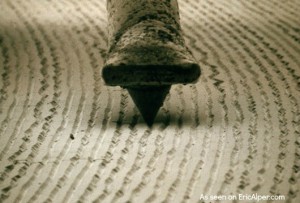

]]>When it comes to listening to vinyl, NYC artist Rutherford Chang antithesizes what Franco Moretti identifies as the “typical reader of novels” in Britain up to about 1820 (Moretti 71). Instead of “a ‘generalist…who reads absolutely anything, at random’” (Moretti 71, quoting Albert Thibaudet), Chang listens to and collects anything, mostly at random, of a very specific corpus: copies of just one edition of one album, “the Beatles[’] first pressing of the White Album” (Paz np). To exhibit and expand this collection, which currently stands at “693 copies” (out of the over three million copies that comprise the 1968 “limited edition”), from January to March 2013 Chang occupied “Recess, a storefront art space in SoHo. It’s set up like a record store…and visitors are invited to browse and listen to the records. Except, rather than sell the albums, I am buying more” (Paz np). While there, Chang listened to White Albums all day, “recording the albums and documenting the covers” (np). Each record, being vinyl, bears its own record of needleworked grooving; many a cover, being once famously white, has been personalized with doodles. These covers Chang “put up on the ‘staff picks’ wall” – a topographized supercut. As for the records, “[a]t the end of the exhibition, I will press a new double-LP made from all the recordings layered upon each other. It will be like playing a few hundred copies of the White Album at once, each scratched and warped in its own way” (np). In the meantime, Chang released a preliminary effort onto SoundCloud, “White Album – Side 1 x 100”: one hundred White Album Side Ones playing simultaneously.

On what scale is Chang’s a scalar reading project? How does a noisy audio palimpsest multiplying “one” object compare with the pristine genre-spanning graphs of Moretti or the intricate Göethe-corpus topologies cited by Andrew Piper?

It’s tempting to dismiss Chang’s White Album remix as simply the synchronic equivalent of a less sophisticated “vernacular” of distant-reading like the supercut. But Ian Bogost’s proposal that object-oriented ontologists need to graduate from the logocentrism of writings which do ontology in theory, to the carpentry of crafted objects that put ontologies into practice (e.g. 91-2), suggests that graphing-objects similarly needn’t be constrained to the logo-visual. Can the “palimpsest” component of Chang’s clearly praxis-oriented project be considered, then, as “auditorizing” data in the same way that one of Moretti’s graphs visualizes data? A pertinent question, given “today’s growing interest in the field of information visualization” (Piper 388).

After all, what is graphic representation? “Graphing,” as the etymology suggests, is a form of writing, which is a form of drawing. As Piper points out, “Friedrich Kittler’s argument, of the two-thousand-year-old antipathy between the alphabetic and the numerical[,]” is a “false notion” (380). Nonetheless, the invisible Cartesian latticework gridding any typeset page, into whose discursive position of “prose” most writing gets indifferently wrapped, has continuously disarticulated graphemic writing from the genre of alphanumeric graphical representation. Notably the same, however, cannot be said for music. From its earliest forms, well before Descartes and de Fermat, the musical staff makes little secret about its dimensionality: pitch vs. time. But: “non-musical” texts encode sound no less! They, too, graph sounds against time, within a limited repertoire of graphemes (e.g. 26 letters vs. 12 tonic pitches). Thus, while literary analysis may have preoccupied itself with “the two-dimensionality of the page or the three-dimensionality of the book” (Piper 383), its broader problem has been that it would not even have articulated its conceptions of the page and book as such, for only recently has it begun to consider its objects in dimensional terms whatsoever. Meanwhile, graphing (alphabetic writing) and graphing (alpha-numeric charting) and graphing (musical scoring) have remained distinct. And a musical graph is expected to be performed aloud, with the body, whereas a philosophical or statistical graph is expected to be performed in silence, with the head. Cartesian plane indeed.

Sound, in short – by which I don’t mean speech – has been systemically excluded as a medium for philosophy, let alone for demonstrative data representations, and this has everything to do with philosophy’s logocentric tradition in emphasizing content over form, music being strongly articulated to the latter. But if we re-articulate the above various forms of writing as graphings more broadly, can we then likewise re-articulate any performance of a graphing as itself a form of graphing, even if this performance is sensually other to the visual (as the iconized data of Piper and Moretti, despite their iconoclasm in other respects, tends to emphasize)?

Things become clearer if we elaborate further on what graphing (i.e. writing) is, and illustrate with vinyl. In Vilém Flusser’s description, “writing…was originally an act of engraving. The Greek verb ‘graphein’ still connotes this…. [T]o write is not to form, but to in-form, and a text is not a formation, but an in-formation” (Roth 26). It is such information that we find grooving a vinyl record: a form of information whose curves, unlike these graphemes that I type, is more readily articulable to the curves of information that discourse has arbitrarily distinguished as graphing (see Figs. 1 & 2). Indeed, confusions have arisen at all because we speak of information in such logocentric terms as Flusser himself does, whereas information theorists speak of it in terms of waves, frequencies – something that writers like Piper do evoke with statements like, “any textual field is at base a configuration of differential repetitions” (394). Whereas, now that we’ve re-articulated graphing as information, we can see how the curves of Figure 2 could just as easily be transfigured into audio as could the curves on the vinyl. It would be up to us listeners to re-articulate our logo-visual biases to interpret the “audiograph” as well as we can its visualized score. But is it just our lack of familiarity with interpreting an “audiograph” as a graph that would other it as comparably “messy” (in John Law’s term), or can such graphs simply not compare with pristine Cartesian visuals, say for reasons of transfiguration?

The approach to this question is rolled up in what the convergence of Figures 1 and 2 illustrates: the zero-point at which “distant” and “close” break down into “a continuous spectrum of focalization” (Piper 382). This is a useful place to begin discussing Chang, whose “1 x 100” audiograph intuitively seems more of a “distant reading” than the audiograph from a single record. But, having dismissed the distant-close binary in favour of an ontology of surface relations, we shall see that “more” no longer necessarily means more, nor “less” less. If all graphs record regularities of information, then the question becomes not about perspectival proximity, nor even exactitude, but about how and what each object – 1 White Album vs. 100 White Albums simultaneously – graphs differently. What do the regularities of one single White Album measure in comparison with the overlayed regularities of one hundred White Albums?

Close-distant reading: We needn’t hear 100 versions at once for us to know that our single copy is not singular, that the “object” we listen to is much larger than its packaging’s pretense to unity; indeed, the fact that it is not one-of-a-kind is likely how and why we and the object found each other in the first place. For Foucault, the very fact that we have a White Album playing at all means that it is discursively sanctioned, corresponding to a discursive statement, a regularity within a field of discourse: the grooves of a single White Album already graph a regularity concerning White Albums. Like the statement “QWERTY,” produced by a standard keyboard, any printing of a White Album is a statement produced by a similarly standardized mass-printing device programmed to print the White Album from a “master” copy or image, such that any single vinyl record graphs a regularity of discourse, a record of the process of inscribing White Albums with the grooves that constitute White Album-ness. A White Album graphs, more accurately than its hundred-fold multiplication, the pristine Gaussian “mean” of White Album articulation. Mass production’s claim to mass identity is its mass delusion, but an individual album is nonetheless a graphical index of its mass-media ur-stamp. Indeed, this is so because it is such standardization’s goal: to distribute the closest approximation of the Same, so that a claim for Sameness may be made, a common-place created.

Distant-close reading: What do the 100 albums played at once tell us, then? We needn’t listen to know that there will be much “noise”; indeed, judging by the present recording, if Chang carries through with his plan to mash up his 600+ records, we would hear nothing but noise. What, then, does this audio-topography do? Ostensibly it graphs the relative fluctuations between 100 versions – but not in any distinct way. Can we distinguish all the tracks (and their interrelations) as we might in a visual representation? Indeed, there is “noise” because there is information lost – each element in the audiograph interferes with every other. Or is the noise we perceive as much a function of our bias to the logo-visual? If for topology “the ‘object’ is merely the identification of a visual thickness” (Piper 384), then Chang’s project fits the description, but does this hold if topology considers “reading” only as “a deeply visual experience” (Piper 387, emphasis added)? Alternatively: Friedrich Kittler engages in an alien phenomenology of the phonograph to describe its recordings as constituting the real: “The phonograph does not hear as do ears that have been trained immediately to filter voices, words, and sounds of noise; it registers acoustic events as such. Articulateness becomes a second-order exception in a spectrum of noise” (Kittler 23). Such engagement raises the question: Is (topo)graphing unable to deal with acoustic events as such? Would the noise be better approached from the phenomenology of an alien object?

Works Cited

Bogost, Ian. “Carpentry.” Alien Phenomenology, or, What It’s Like to Be a Thing. Posthumanities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012. 85–111. Print.

Roth, Nancy A. “A Note on ‘The Gesture of Writing’ by Vilem Flusser and The Gesture of Writing.” New Writing: The International Journal for the Practice and Theory of Creative Writing 9:1 (2012): 24-41. Web.

Kittler, Friedrich A. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz. Stanford UP: Stanford, 1999. Print.

Law, John. “Making a Mess with Method.” Lancaster: The Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University, 2003.

http://www.comp.lancs.ac.uk/sociology/papers/Law-Making-a-Mess-with-Method.pdf

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History – 1″. New Left Review 24 (Nov-Dec 2003): 67-93. Web.

Paz, Eilon. “Rutherford Chang – We Buy White Albums.” Dust and Grooves: Vinyl Music Culture. 15 Feb 2013. Accessed 10 Oct. 2013. http://www.dustandgrooves.com/rutherford-chang-we-buy-white-albums/

Piper, Andrew. “Reading’s Refrain: From Bibliography to Topology.” English Literary History 80 (2013): 373-399. Web.

The post Probe: Phonographs, Maps, Carpentrees appeared first on &.

]]>The post Re-building and re-thinking the Great Wall of China appeared first on &.

]]>

I struggled trying to decide on what object to write this week’s probe. I initially was going to write about a very specific and concrete object with an equally specific purpose, such as a toothbrush, but I found myself continually coming back to thoughts of much more abstract and complicated things. Perhaps I wanted a challenge, but I’ve decided to write this probe on the Great Wall of China. I hope to spark discussion and critical thought on how to classify and distinctively describe objects such as the Great Wall of China.

Originally made with stone and earth about 2300 years ago, The Great Wall of China stands today as a world heritage sight and one of the New Seven Wonders of the World. Believed to be the best way to keep invaders out and to protect China, the wall is a network of fortifications that were joined together to form one wall circa 220 BC. Although about 50% of the original structure does not exist today, preservation remains an ongoing challenge. Problem #1 for me: it is a collection of numerous smaller walls, all built at different times…the network is gigantic and highly “messy”. But, as Law states at the beginning of his article, objects are “networks of relations” (91) – it is as if the complicated networks stemming from the Great Wall are like the wall itself: branches of smaller walls coming from different directions, connecting at certain points along the way.

Actor-Network Theory, as we have already discussed, is based on the concept that all things are related as enactments of strategic logic; everything participates in holding everything together (Law 92). The network of materials that make up the Great Wall of China is immense – stretching out over thousands of years and including the most basic materials from dirt and leaves, to the more elaborate and modern tools used today in restoration. This is not just a wall built around someone’s property to keep the raccoons out – it is a major feat of engineering as well as a cultural symbol.

I found Law’s description of Portuguese vessels to be particularly intriguing. Thinking of the object in terms of what it does in a social relativist view is very different from looking at it with a view of scientific naturalism. These vessels could transport people and objects, enabled exploration and colonial domination, had the ability to navigate in unfamiliar territories, and could be updated or expanded. From a scientific naturalist perspective, a vessel is made up of a large collection of smaller bits and pieces to serve the larger purpose of a fully functioning vessel. If parts of the material network (hull, sails, ropes) do not function, then the object is no longer what it was intended to be (Law 93). But, it can still function without sails if one saw the vessel in terms of social relativism; the vessel may no longer be homeomorphic if it is “broken or torn” in some way, but it can still function – just as you or I could live a healthy life with only one kidney.

Considering the Great Wall of China as a result of society and human behaviour from a social relativist point of view, it was meant to protect from invaders, but it also ended up serving other roles like transportation routes, and providing employment.

Law asks the question early in his article: “What is an object if we start to think seriously about alterity?” (92) Under what circumstances can an object be deformed without changing its shape? (95). Since the Great Wall of China has undergone construction and been rebuilt, is it still the same object? It is being restored today using new materials, new methods, modern techniques, and new tools. It will never be what is originally was, so is it “correct” to still refer to it as the same object? If the Mona Lisa was damaged and another artist restored it, would people still wait in line to see it? Is it still the Mona Lisa even if someone else has become part of the art itself? This is a particular question I would love to further discuss in class to gain further insight into what you all think.

Drawing from Bogost’s description of carpentry, the “practice of constructing artifacts as a philosophical practice” (92), the Great Wall of China is an expression of culture, knowledge and philosophy. Bogost includes a quote by Latour, “Knowledge does not exist…Despite all claims to the contrary, crafts hold the key to knowledge” (110). Creating the longest man-made object is indeed an expression of knowledge (and dedication!), but how long did the Chinese see this wall lasting for at the time it was being built? Since there are always multiple modes of expression and forms that expression can take, was a wall really the best method of protection for the Chinese? As Jared Diamond is quoted, “The major events and innovations of human progress are the likely outcomes of material conditions, not the product of acute, individual genius” (Bogost 87). Thinking in terms of material history, with the materials that were accessible at the time the Chinese needed protection, it made sense to use those materials to construct a wall to keep invaders out.

“The major topic of object-oriented philosophy is the dual polarization that occurs in the world: one between the real and the sensual, and the other between objects and their qualities” (Harman 4). If object-oriented ontology is about studying how objects exist and interact with one another, while contending that everything exists equally, is the Great Wall existing in a different sense than it did when it was first built? It is interacting with humans in a very different way than it was intended to. Today, you have to pay a fee to stand on some parts, and there are restricted hours you are permitted to visit.

I will leave you with an excerpt of a video from a series “An Idiot Abroad.” Created by the British comedian Ricky Gervais, it tracks Karl Pilkington, a fellow actor, on his journey to discover the wonders of the world. He sums up his experience by describing it as “the Alright Wall of China.” Do you agree with his reasons for not being impressed with it? How does one write about and describe an object that has existed in different contexts across time? Does it get described differently at specific points along the way, or are we to see it as one general description encompassing all possible networks and associations?

Works Cited:

Bogost, Ian. “Carpentry.” Alien Phenomenology, or, What It’s Like to Be a Thing.Posthumanities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012. Print. 85–111.

Harman, Graham. Selections from Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy. Winchester/Washington: Zero Books, 2012.

Law, John. “Objects and Spaces.” Theory, Culture & Society 19.5/6 (2002): 91-105

UNESCO. “The Great Wall.” Accessed 9 October 2013: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/438.

The post Re-building and re-thinking the Great Wall of China appeared first on &.

]]>The post Narrative Multiplicity, Relative Beginnings and Discourse Networks appeared first on &.

]]>1966. Copies of Gregory Rabassa’s translation of Julio Cortázar’s Rayuela begins to circulate…

Hopscotch receives critical and popular success for a literary work. Much attention relates to the book’s TABLE OF INSTRUCTIONS:

In its own way, this book consists of many books, but two books above all.

The first can be read in a normal fashion and it ends with Chapter 56, at the close of which there are three garish little stars which stand for the words The End. Consequently, the reader may ignore all that follows with a clean conscience.

The second should be read by beginning with chapter 73 and then following the sequence indicated at the end of each chapter. In case of confusion or forgetfulness one need only consult the following list:

(Hopscotch, TABLE OF INSTRUCTIONS)

The inclusion of THE TABLE OF INSTRUCTIONS is interesting, considering most books don’t need one. Usually when beginning a book, you read from left to right horizontally, down vertically, flip page and repeat until the back cover has been reached or the book is put down. Cortázar’s instructions, however, propose that multiple textual realities exist simultaneously within the same text, and the narrative trajectory can be materially altered by the reader’s choices. The first order is the traditional one, but instead of reading to the back cover, ‘the end’ occurs in chapter 56 (out of 155) on page 349 (out of 564). On the following page, another section begins, under the heading FROM DIVERSE SIDES: Expendable Chapters. Thus, Chapter 57 is the first Expendable Chapter. But Chapter 57 is serially listed as 57/155 and is also Chapter 84/155 in Cortázar’s second suggested order. Further, Chapter 57 is variable X/155 in any other reader generated schema. Obviously each choice, order, and variation the reader makes creates a different text.

THE TABLE OF INSTRUCTIONS is also interesting because it negates the traditional TABLE OF CONTENTS. How can there be a table of fluctuating contents? How can there be a beginning, a primary referent, or a definitive end, if the narrative is being created by the reader’s decisions? At first glance, it seems that Hopscotch just privileges the reader’s subjectivity while negating the author’s authority. But if every reader’s subject position is materially privileged within their own re-constituted narrative, doesn’t that negate the interpretive significance of each individual reading? If all interpretive stances are explicitly subjective interpretations of different texts, can interpretative stances have relational validity?

Michel Foucault’s archaeological approach to history is similar in that he seeks to destabilize the continuity of historical narratives by introducing series of relative beginnings.

Continuous history is the correlate of of consciousness: the guarantee that that what escapes from it can be restored to it; the promise that it will some day be able to appropriate outright all those things which surround it and weigh down to it, to restore its mastery over them, and to find in them what really must be called [...] its home. The desire to make historical analysis the discourse of continuity, and make human consciousness the the originating subject of all knowledge and all practice, are two faces of one and the same system of thought. Time is conceived in terms of totalization, and revolution never as anything but a coming to consciousness. (AME 301)

History is an analog for consciousness in the sense that both are conceived of as being, potentially, a primary referent. Situated within a totalized temporality, continuous historical narratives are discovered by the enlightened human subject. But these two correlatives necessitate reciprocal support. If “discontinuity was that stigma of temporal dispersion which it was the historian’s duty to suppress from history” (AME 299), “history had to be continuous in order for the sovereignty of the subject to be safeguarded” (AME 333). Further, any conception of historical continuity that piggy-backs while championing the cognizant human subject, Gumbrecht points out, can only exist within a specific notion of temporality: ”As long as we imagine time as a sequence of moments that link the past with the present, we presuppose that the observations, actions, and events attributed to subsequent moments on this continuum are connected by a principle of (however “soft”) causality” (Gumbrecht 401).

What Foucault, Cortázar, and Gumbrecht do, is break up the subject oriented line of causally based historical continuity. Foucault, for his part, creates an archaeological model that “allows us to treat history as a set of actually articulated statements, and language as an act of description and an ensemble of relations linked to discourse. (AME 287) Cortázar, for his part, disperses his own subjective punctuation throughout the text(s), forcing readers to determine their own path, acting upon their their own textual gestures. Of course, the book’s multi-dimentional structure assures that the text has no finality. It can be continually revised, revamped, reassessed, and reinterpreted. But can we really attempt to relate our interpretation of the text if were all reading different texts (which of course, we are all always doing, even if its not normally so obvious)? Cortázar seems to eliminate his own subjectivity and diminish the the reader’s perspective within the mummers of discourse, to a point where we can talk about the underlying structures or the materiality of the text, but not so much about the narratives themselves. Perhaps Cortázar and his readers enact the anonymous murmuring Foucault seems to desire.

This is not to say that Cortazar’s Hopscotch and Foucault’s Archaeology of Knowledge are directly related, but rather that each text represents a statement or node within a single discourse network, or, actually, a plethora of relative discourse networks. In these discourse networks, Deluze might point out, “science and poetry are equal forms of knowledge” (Deluze 15). Rayuela is published the same year as Burroughs’s The Ticket that Exploded (1962), and Thomas Pynchon’s V (1962), two texts described as anti-novels. All of these texts share with Foucault the desire to displace subjectivity within a textual murmur. Try to find the authorial subject in The Ticket that Exploded, a novel where parts are created by Burroughs and Gysin’s cut-up technique, in which the author cuts up sections of text, re-arranges them with other cut up sections of text. This technique literally disassembles the authorial subject by re-ordering linear text fragments. It is similar to Cortázar’s suggested sequential cut ups, except, instead of the reader choosing intervals of chapters, Burroughs is cutting up sentences, or words, and re-arranging them himself, often at random, or to a predetermined structure.

We also find Borges’s texts within this discursive network. In the preface to The Order of Things, Foucault quotes Borges’s Chinese Encyclopedia. In Hopscotch, a book heavily indebted to Borges, Olivera (the protagonist) says to himself, “the theory of communication, one of those fascinating themes that literature had not gone into much until the Huxley’s and the Borgeses of the new generation came along” (Hopscotch 152). Borges texts, like Hopscotch, create play as readers work through a series of narrative levels . Often, perhaps in mockery of real historical works, Borges conjures up fictional source texts that inspire his narrator’s or his own discussions of literature. Such is the case in Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, where the fictional narrator has found an encyclopaedia of a fictional planet. Attempting to work through the meta levels, false starts, and non-endings within the text, I am often reminded that I feel almost exactly the same way when I read real texts about real historical narratives. Foucault, as well, draws inspiration from Borges’s labyrinthian relationships between history and narration.

Borges also breaks up Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius with fictional footnotes, a strategy used by many, but perhaps nowhere as recently and notoriously than in David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (1996). Infinite Jest is published two years before Roberto Bolaño’s Los Detectives Salvajes (1998). These books are directly influenced by Cortázar and Burroughs’s multi-sectional narrative techniques, reverence (or irreverence) for meditations on mediations, yet also, I would argue, embody a late 1990′s aesthetic explicated in Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics (1998), which, not coincidentally, begins circulation at roughly the same time. While Bolaño, Bourriaud and Wallace certainly read Borges, Cortázar and Foucault, it is uncertain whether of not they read each other’s work before their own major works were published. This suggests that the discourse network I consider them to be apart of assimilated similar texts and ideas, which were reformulated into three different texts in three different languages in three different countries. The near simultaneous circulation of these seemingly unrelated texts emphasize Foucault’s concept that the discourse networks we are apart of allows and limits the discursive practices we pursue. As Foucault suggests: “No book exists by itself. it is always in a relation of support and dependance vis-à-vis other books; it is a point in a network–it contains a system of indications that point, explicitly or implicitly, to other books, other texts, or other sentences (AME 304).

Finally, I would like to point out something totally obvious. The theoretical dismantling of historical narratives, primary referents, and cognizant subjects, did not remain solely within the realm of abstruse theories and destabilized aesthetic experiments. The two most common forms influenced by Foucault’s relative beginnings and Cortázar’s multi-narrative technique are probably the Choose Your Own Adventure Novels, and more recently, video game culture. While children reading Choose your Own Adventure Novels probably weren’t moonlighting The Archeology of Knowledge on the sly, they were still working through some of the same ideas. And people playing video games, who have never read Cortázar, are enacting similar narratorial transgressions, which makes gamers, children of the eighties, Foucault, Cortázar, Borges, Bolaño, Wallace, Bourriaud, and us, all relational members of a discourse network concerning relative beginnings and multiple endings.

Works Cited:

Cortázar, Julio. Hopscotch. Trans. Rabassa, Gregory. New York: Random House, 1966. Print.

Deleuze, Gilles. Foucault. Trans. Hand, Sean. London: Athlone, 1988. Print.

Foucault, Michel. Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology. Essential Works of Foucault, 1954-1984. Vol. 2. New York: New Press, 1998. Print.

Gumbrecht, Hans Ulrich, and Karl Ludwig Pfeiffer, eds. “A Farewell to Interpretation.” Materialities of Communication. Writing Science. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1994. 389-402. Print.

The post Narrative Multiplicity, Relative Beginnings and Discourse Networks appeared first on &.

]]>The post The Relative Beginnings of Cap Badges and Rulebooks appeared first on &.

]]>How do relative beginnings and surface relations help structure statements?

In turn, how do these statements dictate the rules that structure the production of texts, objects and discourses?

Cap Badge and Rulebook

My research on the contributions of non-Irish people to the Irish traditional music soundscape in Montreal has led me to reflect on the city’s Scottish music community (specifically that of the pipe band community, in which I am an active participant).

The object above is a representation of the cap badge of the Montréal Pipes and Drums, which was founded in 2000. It is the only pipe band in Montreal unaffiliated with an army regiment or a police force.

What statements can be identified in the cap badge? This discussion knows few bounds. One might examine the (bilingual) text on the cap badge, situating it within two assemblages (one musicological, related to the world of pipe bands, and the other geographico-cultural, related to the city of Montreal). The visuals on the badge add something of their own. The small bagpipe and drum and the distorted Montreal municipal flag are merely visual representations of the text, and the stylised dragons on each side could be interpreted as signifying some form of imagined Celtic identity. One could go further, and consider the political reasons for the flag’s distortion…But that would be close reading, now wouldn’t it?

Zooming out, we notice the cap badge stands in a particular relationship with other elements of discourse in the piping and drumming tradition. This badge is worn in a glengarry, one of the most common headdresses worn by pipers and pipe band drummers. In this highly visible position on a Highland uniform, cap badges thus serve as signs of belonging to a group – generally a pipe band, a regiment, or a Scottish clan.

Not every piper wearing a glengarry necessarily wears a cap badge. However in cases where the cap badge is mandated as part of a band uniform, not wearing it could result in disciplinary consequences, especially in the stringent contexts of military or police pipe bands. This would bring pipers and drummers to internalize the necessity of displaying their cap badge in the proper circumstances. Whereas Foucault’s techniques of discipline are primarily focused on “controlling the location of individuals, and the production of work” (Markula and Pringle 2006, 41), we have here a manifestation of Foucauldian structured subjectivity where the individuals producing work in a given location must also display group cohesion in terms of dress and appearance.

This also brings to mind Foucault’s conception of anonymity, which “is to manage to obliterate one’s proper name and to lodge one’s voice in that great din of discourses which are pronounced” (Foucault 1998, 291). Whereas Foucault expresses this notion in terms of language, it may also be applied to pipe band uniform requirements. The wearing of standardised uniforms both obscures variation in individuals’ appearance (to the extent that it becomes more difficult for a single person to stand out), and situates these individuals in the broader discourse of Scottish culture (or Scottish-North-American culture, in the case of the Montréal Pipes and Drums). A number of statements may serve to structure, uphold and perpetuate this discourse. The rules governing pipe band competitions (a important performance setting for many pipe bands) is an important one.

The rulebook of the Pipers and Pipe Band Society of Ontario (PPBSO) states:

As a minimum, all competitors shall be attired in head dress, shirt, kilt, hose and shoes. Acceptable items of apparel include the following:

1. Head Dress: Feather bonnet, Glengarry, or balmoral

2. Shirt: Collared shirt. More formal dress may include a military-style doublet (for which a shirt will not apply, Prince Charlie-style jacket, police/military-style jacket or vest. Tie is optional, but encouraged.

3. Kilt: Kilt (with sporran) or highland trews

4. Hose: Knee-length hose (not applicable to trews)

5. Shoes: Oxford-style dress shoes or ghillie brogues (PPBSO 30).

The inclusion of a headdress in the required attire for competitors helps fix the cap badge into the broader assemblage of pipe band uniforms. It is not sufficient to merely play the music of the pipes and drums; one must also look the part while playing it. This in turn might require displaying a cap badge on one’s glengarry.

I should emphasize that this section of the PPBSO rulebook is titled “Proper Highland Dress”. This title alone suggests a cultural standard worthy of being upheld and protected against those who might violate its dictates. As Deleuze writes, “…statements refer back to an institutional milieu which is necessary for the formation both of the objects which arise in such examples of the statement and of the subject who speaks from this position…” (9). Indeed, what is a hospital or clinic without a doctor, and a doctor without a hospital or clinic? Similarly, what is a piper without a uniform? Something of an anomaly, one might say.

Anomalies

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z2uzh0sP3Zw

This video shows the Oran Mor pipe band (a high-level competition band) from Albany, NY, playing in civilian clothes at the Ohio Highland Games in June 2008. The band’s bus caught on fire on the way to the Games, leaving many of their uniforms unusable. They were allowed to compete anyway, given the unfortunate circumstances that left them without proper Highland dress. It should be said, however, that the band was – and remains – firmly established in the community of practice of pipe band competitions. That is to say they were not a bunch of upstarts trying to challenge tradition by playing in jeans and T-shirts. Indeed, the rest of the band’s performance at these Games did not deviate from the standard protocol of pipe band contests (marching in formation, starting their set of tunes with three-beat rolls, forming a circle, etc). Only their dress was different.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LdjY6oy4Y2c

This video presents another anomaly; the piper here is kilted, but plays the Imperial March (a tune firmly outside any conventional bagpipe repertoire), while wearing a Darth Vader costume and riding a unicycle. The emphasis here is not on the Scottish tradition of military music, but on the humour of the set-up. Interestingly, the bagpipe-kilt combination serves to anchor the performance in a discourse of Scottish music (albeit on its outskirts), despite the performance’s dissonance in terms of apparel and its overall humorous character. Think of it this way: how would the video have been different had the piper been wearing jeans? Or underwear?

Culture with a history

A deeper look into the past would reveal earlier, hidden beginnings to the assemblage that unites the Montréal Pipes and Drums cap badge and the excerpt from the PPBSO rulebook. One might examine the received wisdom that the incorporation of Highlanders into the British Army in the eighteenth century saved bagpiping at a time when the instrument was falling out of use. One might also consider Hugh Trevor-Roper’s research on the invented nature of the tradition of Highland dress. The kilt, he concludes, was “first designed, and first worn, by an English Quaker industrialist, and [….] it was bestowed by him on the Highlanders in order not to preserve their traditional way of life but to ease its transformation: to bring them out of the heather and into the factory” (22).

Were Foucault alive today (and, who-knows-why, writing about pipe bands) he might discount this earlier history completely. In his own words: “It’s always the relative beginnings that I am searching for, more the institutionalizations or the transformations than the foundings or foundations” (1996, 46). Instead, he may be tempted to view the Montréal Pipes and Drums cap badge as merely a tiny stream, fed by the rains and snows of the Scottish military tradition, flowing and blending into the grand river of global Scottish cultural history. This would be in keeping with his understanding of history in Western civilization as a procession of auto-erasing events: “…in a culture like ours, every discourse appears against a background where every event vanishes” (Foucault 1998, 292).

For Deleuze, a statement “[…] is inseparable from an inherent variant. Consequently, we never remain wholly within a single system but are continually passing from one to the other” (5). The interplay between the cap badge and the rulebook excerpt illustrates this quite well, insofar as they are both part of the same cultural assemblage, yet situated in different, though connected, positions within this assemblage. Despite being a firmly civilian band with no links to a police force or to the army, the Montréal Pipes and Drums employ a cap badge as part of their uniform, in keeping with the prevalence of these badges in both civilian and non-civilian bands. This prevalence in turn derives from the historic use of regimental cap badges in the British military. The roots of the statements here lie deep in the past, far removed from the discourse whose surface is displayed by the objects this probe has considered. For all of Foucault’s disinterest in “foundings or foundations” (1996, 46), relative beginnings are necessarily constructed from at least a few absolute ones.

Works Cited

Deleuze, Gilles. Foucault. Trans. Hand, Sean. London: Athlone, 1988. Print.

Foucault, Michel. Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology. Essential Works of Foucault, 1954-1984. Vol. 2. New York: New Press, 1998. Print.

Foucault, Michel. Foucault Live: Interviews, 1961-1984. Semiotext(E) Double Agents Series. Ed. Lotringer, Sylvère. New York: Semiotext(e), Columbia U., 1996. Print.

Markula, Pirkko, Richard Pringle. Foucault, Sport and Exercise: Power, Knowledge and Transforming the Self. London and New York: Routledge, 2006. Web. http://books.google.ca/books/about/Foucault_Sport_and_Exercise.html?id=Onp33gwJBS0C.

Pipers and Pipe Band Society of Ontario. “PPBSO Rule Book.” 2013. Web. http://ppbso.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/PPBSO-Rulebook-2013.pdf.

Trevor-Roper, Hugh. “The Invention of Tradition: The Highland Tradition of Scotland.” The Invention of Tradition. Ed. Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger. Cambridge: University of Cambridge, 1984. Web. http://www.columbia.edu/itc/journalism/stille/Politics Fall 2007/readings weeks 6-7/Trevor-Roper, The Highland Tradition.pdf.

The post The Relative Beginnings of Cap Badges and Rulebooks appeared first on &.

]]>The post Dead Celebrity Author Reads to the Society of Strangers appeared first on &.

]]>http://www.festival-fil.qc.ca/2013/letranger-lu-par-albert-camus/

The post Dead Celebrity Author Reads to the Society of Strangers appeared first on &.

]]>