The post “It’s all about building trust”: An interview with Joanna Berzowska of XS Labs appeared first on &.

]]>Joanna Berzowska founded XS Labs in 2002 at Concordia, where they focus on “the development and design of electronic textiles, responsive clothing, wearable technologies, reactive materials, and squishy interfaces.” Previous to XS Labs, Berzowska studied and worked at the MIT Media Lab, and she co-founded International Fashion Machines with Maggie Orth. She holds a BA in Pure Mathematics and a BFA in Design Arts.

The kind of work that Berzowska engages in is profoundly interdisciplinary and crosses distinctions that we might automatically put up between design, industry, art, and theory. Her work has been shown at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York, the V&A in London, and at Ars Electronica in Linz, Austria, among others. Her lab at Concordia is located on the 10th floor of the EV and is part of the textiles cluster.

I met Joanna Berzowska for a coffee in St. Henri on December 10 to discuss wearable technology, her experience working at the MIT Media Lab, the agency of things, and what she believes is important for building an interdisciplinary space.

First of all, why do you call XS Labs a “lab”? Instead of say a “studio”? With International Fashion Machines, for example, I notice they call themselves a “company” — why “lab”?

I think part of the reason I originally called it a lab was just out of habit, because I was at the MIT Lab, and “lab” implies a kind of research culture… I’m thinking about it right now, because I guess I’ve never thought about it in depth… So part two of my answer is that it was a very direct, easy way of referencing research culture. Part three is a very strong emphasis at the time — when I was hired by Concordia fourteen years ago — to re-brand the institution as a research institution as opposed to a teaching institution. So when I was hired, I was basically told, your teaching doesn’t matter, your service doesn’t matter, all that matters is your research and how much money you raise. I think it was a turning point for the university, it was like the institution swung one way, because very strongly it was trying to position itself as a viable research institution at the time. Since then, the pendulum has really swung the other way. Now I think with the new president, Alan Shepard, he’s trying to find a comfortable middle that supports research as well as entrepreneurship, but at the same time recognizes that Concordia will never be a pure research institution and that’s what Alan always says — we can’t compete with McGill, we can’t compete with Ivy League–type schools, Concordia is unique. But when I was hired, the push was really, for a year or two, it’s all about research. So that’s part three of my answer, which is political in a sense. Going back to part two, it was important that “lab” reference research culture in a direct way, especially being in the Fine Arts, where, at that time, all the funding bodies and all of the potential sources of research income did not recognize what we now call “research-creation” as a viable way of working.

What’s interesting is I originally called it “XS Labs,” and even within that there’s an embedded critique. “XS” official stands for “Extra Soft” and it’s about soft circuits, it’s about soft electronics, but of course when you read it, it also sounds like “excess,” so there’s an embedded critique of a kind of contrast between a lot of research in Humanities, which is inherently critical of how we apply technology or how society embraces new changes, and then research in let’s say the sciences or Engineering, which don’t question it as much, but really just pursues innovation. The reason I chose the word “XS” was to have this critique. A lot of what I’m doing is in Engineering, science-type research, and we’re just going to put as much electronics as we can into all of these textiles and wearables, but, being in the Fine Arts, I’m also aware that we have to do so in a very deliberative, interrogative way, and question it at each step of the way. So that’s very much the tradition of XS Labs. And also, since XS Labs started, it’s XS Labs, colon, and what comes after the colon has evolved. So now I do refer to it as a design research studio. I’ve examined every couple of years the kind of work that we do, and these days I call it a design research studio, but the name is still XS Labs, so I guess I just want it all [laughs].

You’ve worked with the MIT Media Lab’s Tangible Media Group. This semester we’ve read a bit of Stewart Brand and have talked about California ideology and its very utopian take on technology. I read in an interview with you [with Jake Moore] where you were talking about researchers such as [Steve] Mann or [Hiroshi] Ishii who work with wearable technology in a way where it’s an exoskeleton or a kind of protective layer. And I was wondering if “Extra Soft” is a response to this kind of ethos that came out of working with the Media Lab and this situation where technology is celebrated as utopic and where wearable technology is something protective.

Yeah. So at the Media Lab there was definitely a strong gender divide actually, between how wearables were tackled by male researchers — and also, maybe coincidentally, the female researchers had more of a background in design or the arts. These are all stereotypes, which unfortunately were instantiated in my experience. So, women who I worked with, like Elise Co, Maggie Orth, who was my business partner for a while, Amanda Parkers, who came later, who’s now very active in the space, and then the dudes that I worked with, who were Brad Rhodes, Thad Starner, who ended up working for Google Glass, and Steve Mann, who’s a prof now at U of T [University of Toronto] — the women had more of a design and art background. I’m not saying it’s necessarily because of gender that they were more in touch with embodied sorts of questions, perhaps it was because of their past training, but maybe the past training was tied to gender. There was in fact one woman who was a really hardcore engineer, she still is, and she worked with Ros Picard [Rosalind W. Picard], who’s also a woman and also a hardcore engineer, so maybe the background training is more relevant in terms of the women that I worked with who were more interested in what we now refer to as embodied interaction, and considering the body as crucial — they were interested in textiles and the surface of the skin and what I now call beyond-the-wrist interaction —

Beyond the wrist…?

Whereas the dudes were really interested in things that you can manipulate with your hands and head-mounted displays, I was more interested in what happens on the rest of the body. And in many ways what happens on the rest of the body can be considered as dirty or sexual or smelly or provocative, so that doesn’t fit as easily into an Engineering research model, where you don’t have a specific problem to solve. And of course there are many problems, like how do you track baby kicks during a pregnancy, or whatever [laughs]. But, I certainly was more interested in the textiles, the rest of the body, how can we embed computation in textiles rather than attach devices to our bodies. And one corollary of that is also an interest in simpler kinds of computation. So, you know, the more cyborg approach to wearable computing basically strives to develop a computer as powerful as possible that is wearable and portable and now we have them [points to phone recording conversation] — these phones are kind of that, right? So, keep in mind this was twenty years ago, and the idea was, how can we take our computer with us all over the place? And now we do it with our phones, it’s funny. But back then, it was basically, you had to put the hard drive in the backpack, you have to take it all in pieces, have a huge antenna for your satellite GPS, etc. That’s wearable computing very literally, where you wear the same kind of computer that you have on your desk, whereas with my electronic textiles and the soft computation, it wasn’t a computer as you know it from your desk, but computation, how can you have wearable computing that is about simple kinds of interactions or simple kinds of functionality that are more interested perhaps in well-being or pleasure or just everyday experience or communication rather than just taking your computer from your office. That’s where the Extra Soft comes from, and there’s so many references, because also there’s hard science versus soft science.

It also sometimes seems like a lot of wearable technology aims to be “corrective” somehow, but you’re not really trying to “correct” the body. You’re trying to do something different.

“Extend” is usually what I say, whatever that means. Or not bring about some huge productivity gain or something but instead allow us to experience the world in a slightly different way.

To go back to the lab for a minute, is XS Labs one lab space or is it a series of lab spaces now in the EV?

Going back to the lab I realized there was something else that I wanted to say, so I’m glad you brought it up again. Another reason why I called it a “lab” is also that I wanted another way of working with my students. Traditionally in the Fine Arts when you work with grad students, they work on their own individual projects and you maybe advise them, you provide critique, whereas in the sciences and Engineering, they’re research assistants and you pay them for their time and they work not on your project but on a group project. I remember when I first came I was always using the plural “we” even though I only had maybe one research assistant, and people were very surprised, they were like, why aren’t you saying “I” or “my work,” and it’s because I was coming from a research lab culture, where every research paper that’s published has multiple authors, and you don’t work alone, ever, so that was another reason why I wanted to call it a “lab” and to train the students that I hired to not think of it as a job but to think of it as a collective inquiry that everybody will be credited for and everybody will benefit from. There were a lot of issues that we came up against of course where there was confusion between what would be their own individual practice and what is the research lab practice, so I tried to have very specific guidelines around how we credit, what people can take credit for, and how everybody had to credit everybody else’s work, and that’s a whole other kind of discussion.

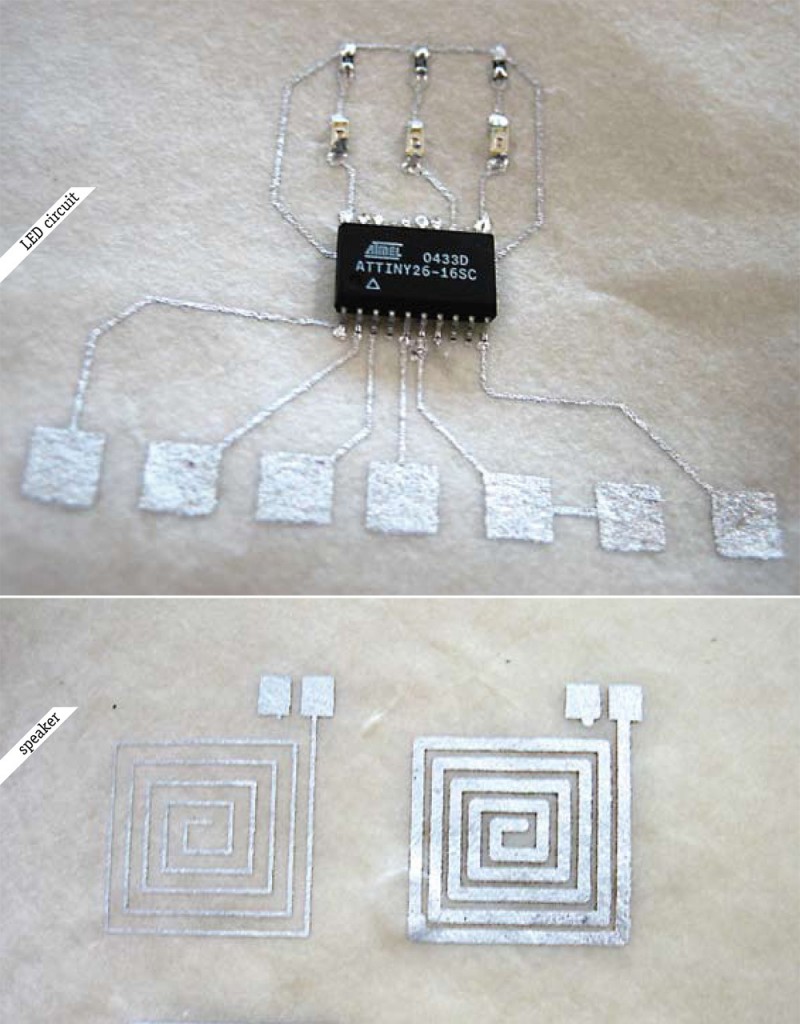

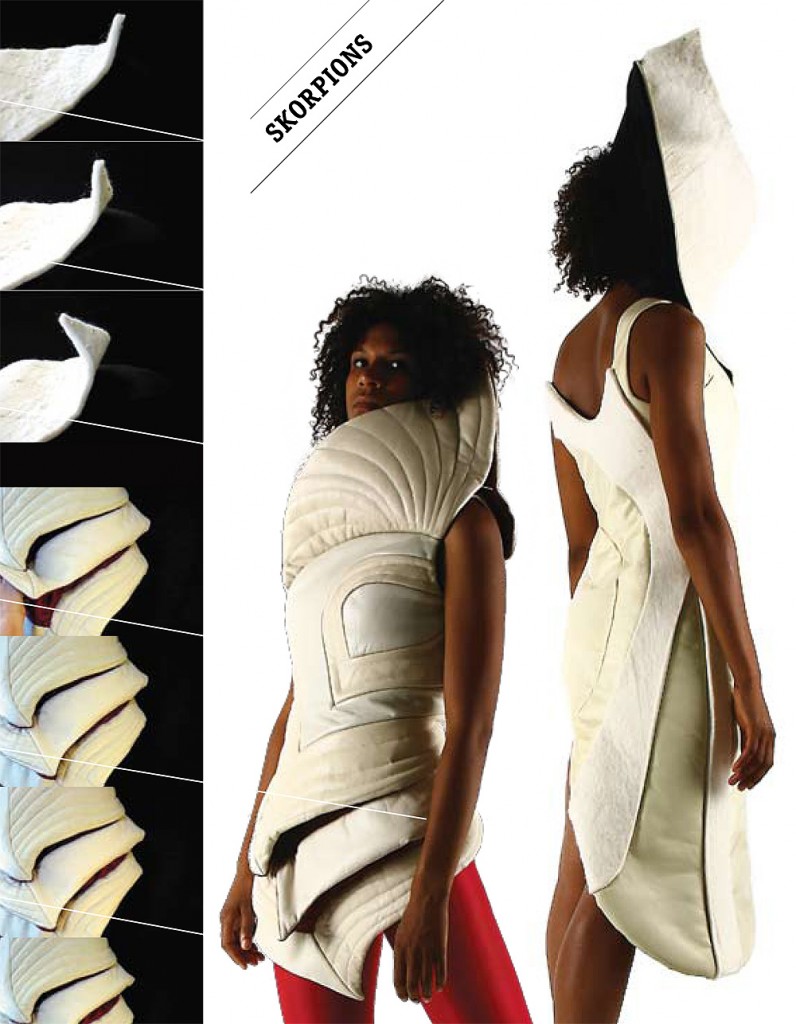

In terms of physical space, we’ve always had one space that’s shifted over the last fifteen years, that’s smaller or larger, that was like our headquarters. Then through Hexagram and other facilities we needed to use or have access to other spaces either through the more technical work we needed to do, like the weaving, or, at one point, I was collaborating with a prof in Materials Science on Nitinol, so we had all of these other spaces where work was done, mostly leveraging specific facilities and expertise. With Materials Science we needed specific furnaces to shape the Nitinol and quench it. We’ve got different kinds of looms or laser cutters. Or, collaborating with École Polytechnique, we’ve had some of our students there developing new fibres. But we’ve always had this little central headquarters. [Nitinol, “also known as muscle wire, is a shape memory alloy (SMA) of nickel and titanium that has the ability to indefinitely remember its geometry”; it is used, for example, in XS Lab’s Skorpions dress.]

When you yourself go into the lab, do you have any daily rituals that you find yourself performing there?

I’ll just say that I was Chair of the department for three years and now I’m on sabbatical and I’m pregnant, so what I do now does not reflect historically. Maybe I’ll just talk about the previous ten years, when there was a strong routine and a strong practice. I always had my days organized — certain days I devoted to teaching and office hours — certain days to service — meaning all the committee work, etc., and all of the research assistants who worked with me, some of them were grad students, some of them were undergrads, some of them were affiliates, there was really a wide range of different ways that I worked with students and research assistants. We had one weekly meeting, where everybody was expected to attend. So that was a sort of ritual where we’d touch base and I would give goals and guidance to everybody for the week. I also had somewhat of a hierarchical structure, where students who had been there longer would be responsible for training some of the younger students, and by younger I don’t mean age, but the newer ones. A lot of the culture in a research lab isn’t about hiring skilled personnel, it’s about training HQP [Highly Qualified Personnel], that’s what we write in the grant proposals [laughs]. So I hire students with potential who don’t necessarily have the skills that I want them to have, and part of what we do is train them. I would pay them to take workshops or classes, but I would also really expect them to teach one another and I would hire very complementary kinds of personalities who could teach each other, and the work is intrinsically interdisciplinary, which is where I think you’re going with this anyway. So that kind of collaboration was really crucial to the success of the work.

I’m very interested in research-creation. Would you say there’s any divide in your work between the research and the creation? Do you have a space more for inspiration and a separate theoretical component, or is that tied together for you?

It’s really tied together because the creation is about questioning technology and doing things with technology that were not possible in the past. So for me, creation is not about what colour is it — let’s talk about garments since we make a lot of those — it was never really about, what does the garment look like — it is, what would it mean to have a garment that moved on your body and moved in an uncomfortable way? What would it mean to have a garment that needs energy but doesn’t have batteries and needs to harness energy from the environment or from somebody else’s body. So for me that’s the creative aspect, and then being able to formulate that into a research question that leads to a successful research grant proposal. And then, working with a team that is very creative, so that the potential answers to these questions that we suggest can be described as beautiful or evocative or playful. And they do get invited to be shown in galleries and museums, which I guess is sort of the institutional stamp of approval for the creation side. I’m not an artist. I’ve never had a solo show as an artist. I really think of myself much more as a researcher. But a big part of my dissemination happens in museums and galleries.

So you wouldn’t consider yourself an artist, but you show in galleries? And your inspiration is not so much connected to the fashion, but connected to questions about technology?

Yes. Like how can we really break down what a garment is. Or what a textile is. And how can we use all of these emerging materials that are being used in aerospace or the automobile industries or whatever, but use them in garments. What kinds of new functionalities would they enable? New forms of expression. New ways of connecting with one another. But also, how would they help us understand the world in a different way? Question the world. The project Caption Electric and Battery Boy is really about questioning our dependence on energy and batteries and portables. The major point there was to create garments that are sort of ridiculous and uncomfortable. And the thematic that runs through it is one of fear and paranoia and fear of natural disasters and protection, so it’s deeply linked. And then in order for me to be able to raise the money that I’ve raised that’s more from the sciences and Engineering, there’s always a very strong scientific or engineering innovation in the project. And I would feel like a fraud if there weren’t.

Do you think with working on very highly funded projects, with industry and with big labels, do you see that as in any way compromising your vision? Or extending it? Do you find that working with big industries provides a positive constraint or something where you have to really compromise your creative work?

It’s a different kind of vision. I don’t see them as contradictory. The obstacle to work in my experience has just been the really kind of overwhelming bureaucratic aspect of administering large research grants at the university, where I ended up just spending so much of my money doing paper work and filing reports and filing expense reports in a thoroughly inefficient way… Industry can’t afford to have the same kind of level of inefficiency that we have in academia… They would go out of business. So that’s super refreshing. Of course then we have a board of directors that we have to answer to. We have to show a business model that would be profitable with an X amount of years. Whether that business model involves being acquired by Google or having sales or whatever, I mean that’s another questions, it’s the VC [Venture Capital] world.

That’s interesting, because usually we see the academy as the place where we can sort of nurture our bigger ideas and industry as a place where we have to compromise. But that’s not your experience?

It’s different ideas. But what’s really exciting is there’s different kinds of industry. And right now with the start-up culture around new technology, it’s all about innovation and wonder and discovery that, sure, you have to have a business model, but that can be viewed as a benefit rather than an impediment… I’ve also worked on projects with creative studios. So industry doesn’t necessarily mean military or medical devices. Industry can also mean Cirque du Soleil. Or working with PixMob, which is a great company, some of my ex students started it. So industry, sure, has to have a business model, and if it’s not profitable, it will go out of business, but it doesn’t mean you don’t innovate or you don’t do exciting work. And sometimes innovation is actually stifled in academia because of all the bureaucracy and paper work. I’m being provocative of course. Because all of the assumptions you’re bringing to that question are true, but there’s also that other side.

You said you don’t see yourself as an artist. What do you think the differences are between art and design?

Everybody is going to give you a different answer. But my answer these days is that art is about one individual and design is about multiple individuals. And of course people will argue with that and I will change my mind eventually, but that’s how I think about it these days. So for me, design fits a lot better into this research model where we have multiple authors for each project. It’s almost like thinking of the research work as a theatre performance, or a play, or an orchestra, where you have a conductor, but then everybody gets credited for their own role. Whereas I find a lot of the art research-creation, it’s still about the one person who takes credit for everything even though they might have a team of people working with them. But also for me design is perhaps a little bit more concerned with the tools, the materials, the processes, rather than like the final moment of showing the piece.

So in design there’s more of a process?

No, it’s not that there is more process, but the process is almost more important than the final piece, for me, okay. Whereas the way that I think of art is that the final artefact is given more importance, culturally. In design research, the process, the materials, the steps you took, are maybe just as important or even more important. And especially when you look at that whole movement of speculative design. Or critical design coming out of the UK, with people like Dunne & Raby. In fact, there isn’t really a final outcome, but it’s all about these trajectories and interrogations and asking “what if?” and showing these speculative processes. Or experimenting with materials. But not necessarily building up to the one artefact that will go into a permanent collection somewhere.

But say with industry you would need to eventually produce an artefact—

—Yeah, you need a product—

—Or else they would be like, “where’s your product”—

Well not necessarily, because also patents are a very viable outcome of industry work. So I’m writing a lot of patents right now with OmSignal. And those aren’t artefacts. That’s IP [intellectual property] that has a high monetary value.

In your work, for example in your Skorpions dress, you describe the dress as parasitic and the wearer as a host, so a lot of agency is given to the actual items that you create. Do you see what you do as somehow aligned with biotech? These garments are almost coming “alive”?

To me, a lot of interaction design I find problematic around the idea that the human is always in control or needs to always be in control versus the idea of giving up control a little bit. And maybe that’s also just a personal philosophy as well. With being a mother. Raising two kids in this very unusual sort of circumstance where I’m not their biological mother but I’m their full-time mother and yet I don’t have the same kind of control… So I think for me, my personal life experience has also influenced the way that I think about interaction design… It’s less about biotech and more about control.

It sounds a little like actor-network theory. We read this also in communication with Stewart Brand. And the fact that objects or technology can dictate the way things go, not necessarily just the human.

One of my favourite quotes from Sherry Turkle is that computers aren’t just a projective medium, but also a constructive medium [See Sherry Turkle, The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit (New York: Simon and Schuster), 1984]. You control or project your desires on them, but they also shape what your desires are.

So it’s a collaboration in a way between the human and the technology? And this is maybe freeing?

Well, the reason I can do these things is that I’m not in an Engineering faculty where each project has to be about solving a specific problem that is then quantifiably successful or unsuccessful. I can produce these projects that exist in this much more qualitative research space, whatever that means. I don’t have to have tables and graphs for each project that I make…. I don’t need to do those kinds of quantitative studies for my research, which allows me to explore these questions that are more — sometimes I say they’re poetic — I don’t have a very rigid theoretical structure for how I talk about these things. But it’s definitely great to have a freedom not to need a quantifiable result at the end of each project.

Is there anything about your lab that you would like to change or that you find problematic? Say, in terms of space?

When we were in that corner space on the 10th floor, that was too small. At one point if you can imagine I had about twelve people working in there with all kinds of sewing machines and electronic stations, so that was nuts. The thing that makes a space successful is to allow everybody to feel ownership over a portion of the space. You need everybody to feel like some small portion of it is their own. To develop a level of trust where people can leave things without worrying about them being either stolen physically or the ideas stolen, so actually working on a culture of collaboration and trust is really important. Definitely in my particular discipline where we need machines there’s always going to be the need to go to other spaces to use different kinds of specialized machines or facilities. But the space itself — it’s more about the culture you create in the space, about exchange, about giving, and the way that I fostered that from the very beginning is by having a lot of parties and 5à7s. It’s all about building trust.

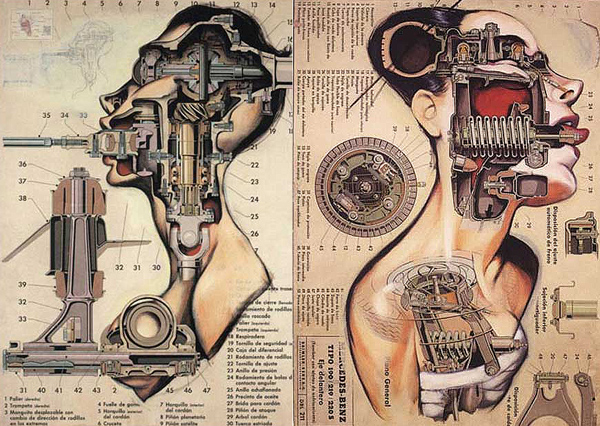

All images taken from the XS Labs catalogue.

The post “It’s all about building trust”: An interview with Joanna Berzowska of XS Labs appeared first on &.

]]>The post Cummins v. Bond: Unmaking the Author appeared first on &.

]]>On the day of July 23, 1926, a strange case passed before Judge Harry Trelawney Eve. On the surface, it seemed like a pretty straightforward matter of copyright in which one Geraldine Cummins was contesting the rights of one Frederick Bligh Bond to a work called The Chronicle of Cleophas. The thing is: Geraldine Cummins was not claiming that she had authored the work instead of Bond; she was saying she was the medium through which the work had been channelled.

The Chronicle of Cleophas, asserted Cummins, had been received incommunicado with the spirit world through the interface of a Ouija board, over a period of about a year or so, and usually in response to questions she had been hired to answer by clients as a paid medium. As for the defendant, Frederick Bligh Bond was employed by Cummins as an assistant and had acted as amanuensis to the various Ouija board messages being received by the medium; in the words of Jeffrey Kahan, “for each of Cummins’s Spiritual communiqués, he [Bond] ‘transcribed it, punctuated it, and arranged it in paragraphs, and returned a copy of it so arranged to the plaintiff [Cummins].’ He further stated, and Cummins did not contradict his statement, that he, Bond, ‘annotated the script, and added historical and explanatory notes’” (92). If you’re confused at this point, you’re not the only one.

We have here a literary shell game, in which authorship is shuffled about until the client is utterly baffled. The difference is that, in a shell game, the client (or “mark”) understands who is doing the shuffling. In the case of a séance no one seems to be the creative center . . . The multiple hands recording the Spirits creates the impression that the creative center is not physically present (Kahan 91).

Who, then, did Judge Eve decide in favour of in 1926 — the medium who channelled the work, or the scribe who wrote it down, arranged, and edited it? And why should we care?

“Walk through a museum. Look around a city. Almost all the artifacts that we value as a society were made by or at the order of men. But behind every one is an invisible infrastructure of labor — primarily caregiving, in its various aspects — that is mostly performed by women.” In her 2015 article “Why I Am Not a Maker,” Debbie Chachra challenges a cultural attitude that privileges the act of making over the more invisible acts behind it, particularly the gendered acts of caregiving and educating. Walk through a text. Look around at the letters and words and margins and paper. It was the mediums of mid-19th-century Spiritualism — an almost across-the-board female labour force — who presented a challenge to one very highly traditional order of men, namely, the order of the author.

What finally materialized in a court of law in 1926 was a practice that had in fact been a booming industry since the Fox sisters started charging admission to rappings on tables in 1848 and mediums started channelling under the moniker of Spiritualist and publishing under the monikers of spirits, which was, according to Bette London, “for some the only way to put themselves forward as authors” (152). This is a practice that literalizes Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar’s statement that “[a] wealth of invisible skills underpin material inscription” (245). The case of Cummins v. Bond is not so much a case that brings to the fore the act of making, nor does it propose a refusal to be a “maker” as Chachra puts it, but rather the act of unmaking.

For the purpose of this probe these themes will remain a little superficial, but the surface is the best place to start here. The title The Chronicle of Cleophas, throughout discussions of Cummins v. Bond, remains just that, a title without a content — the book is rarely considered in its own right and finding a copy of it leads to a ghost town of an Amazon.ca page where The Scripts of Cleophas is (hauntedly) housed. This is exemplary of research into automatic writing, the products of which are sometimes so illegible they cannot even be read, as in the invented language of medium Hélène Smith, who called her script “Martian.” Automatic writing, also called psychography or spirit writing, offers a process of writing in lieu of a product (the continuous verb writing rather than its gerund), and furthermore a process of writing in which the produced work is secondary if not tertiary to the act of creating it; a “transitional object” that connects the “sensory body knowledge of a learner to more abstract understandings” (Ratto 254, emphasis his own).

In his 2011 paper, Matt Ratto outlines his experiments in “critical making,” which address a “disconnect between conceptual understandings of technological objects and our material experiences with them” (253). I was struck by how closely the drawbot, which Ratto had his participants construct in one of his workshops, resembles the planchette that automatic writers used during séances in the 19th century. Whereas the drawbot moves across the paper by a process of mechanization via a small motor, the planchette moves across the Ouija board or piece of paper by a process of automaticity via the participant’s hand, part of what the Spiritualists called channelling, or what a cognitive scientist may call ideomotor action. My main question here is, how could the Spiritualist practice of automatic writing be revived and refigured as a model of critical making — where critical making combines critical thinking, a less goal-oriented form of “making,” and conceptual exploration (Ratto 253)? What would this look like and what are the “wicked problems” it could address?

In my last probe, I explored how sleep could be an interesting object of exploration for a Media Lab; automatic writing by contrast offers a methodology rather than an object — not so much the axis around which questions can be posed, but a way to create the questions in the first place. As sleep unmakes waking and any easy notions around consciousness, automatic writing unmakes the author-function and any easy notions about what it is to write.

The real difficulty is who or what is “Cleophas.” If it be assumed (which nobody can prove) that “Cleophas” has a personal identity of his own and could have been the author of the writing, his evidence would be material. “Cleophas” might be sworn and cross-examined by the process of automatic writing. Instead of being difficult, this might be no trouble at all. Once “Cleophas” is accepted as a real person, the problem of communication involved in swearing him and examining and cross-examining him very likely would not be as difficult . . . (Blewett 24).

Who or what is “Cleophas”? What is automatic writing? How does it work? Is it a shell game, as Kahan suggests? An experiment? A literary device? The fact that the above quote comes not from literary criticism, but The Virginia Law Review, 1926 edition, is indicative of the ripples Cummins v. Bond was causing in terms of conceptions around authorship, marked not least by the quotation marks unrelentingly hovered around the Cleophas in question. “Cleophas,” we could say, is an assemblage, as is, we could also say, any “writer,” as is any piece of “writing.” In “What Is an Author,” Foucault discusses how the 19th century saw the rise of a figure who was not just an author of a text, but an entire discourse, such as “Freud”; “Marx” (228); at the same time, the practice of mediumship that cropped up with automatic writing composed the other side of the spectrum of this canon, folded it back, threw a mirror up to it, but one that hardly anyone was able to see. In the case of Cummins v. Bond, it was the medium Geraldine Cummins who came out victorious, and not Frederick Bligh Bond who’d physically held the pen to record the text. But what is not recognized in either the resolution of this case or the Amazon.ca screenshot above is that on the title page of The Scripts of Cleophas, Geraldine Cummins credits herself as “recorder,” not as “author.” Though she won the case, she was still not granted the right to self-representation. According to Jeffrey Sconce,

Long before our contemporary fascination with the beautific possibilities of cyberspace, feminine mediums led the Spiritualist movement as wholly realized cybernetic beings—electromagnetic devices bridging flesh and spirit, body and machine, material reality and electronic space (27).

It’s a seductive notion, but, really? The mediums of 19th-century Spiritualism often published under the male names of the spirits they were channelling and thus, as London pointed out above, were able to publish at all, and furthermore earn a living for themselves in a position of power as mediums. The history of automatic writing, in contrast to Kahan’s statement, is physically present. These days, our automatic writers are quite literally transitional objects, drawbots: in 2014 alone, one billion stories were generated by Automated Insights’ Wordsmith program (Podolny), which uses NLG algorithms to “write” articles, while tamed automata are often gendered female, such as Siri, Archillect, “Her.” The embodiment of work and working is changing, and so are the questions surrounding it. How could a writing process that is seen as plural from the get-go change discussions around copyright? What does automatic writing say about fanfic, for example, or creativity, labour, or the ways in which these categories are parsed out according to gender? Finally, if the question, as Bernhard Siegert proposes, is no longer “how did we become posthuman? But, how was the human always already historically mixed with the non-human?” (53), then maybe we can also ask: is there any writing, has there ever been, that is not automatic?

Works cited

Blewett, Lee. “Copyright of Automatic Writing.” Virginia Law Review 13.1 (November 1926): 22–26.

Chachra, Debbie. “Why I Am Not a Maker.” The Atlantic, January 23, 2015.

Foucault, Michel. “What Is an Author?” [1969]. Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews by Michel Foucault. Ed. Donald F. Bouchard. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977: 113–38.

Kahan, Jeffrey. Shakespearitualism: Shakespeare and the Occult, 1850–1950. New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1979.

London, Bette. Writing Double: Women’s Literary Partnerships. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999.

Podolny, Shelley. “If an Algorithm Wrote This, How Would You Even Know?” The New York Times, March 7, 2015.

Ratto, Matt. “Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Social Life.” The Information Society 27 (2011): 252–260.

Sconce, Jeffrey. Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2000.

Siegert, Bernhard. “Cultural Techniques: Or the End of the Intellectual Postwar Era in German Media Theory.” Theory, Culture & Society 30.6 (November 2013): 48–65.

The post Cummins v. Bond: Unmaking the Author appeared first on &.

]]>The post Between Language and Materiality: the History of Aphasia Studies appeared first on &.

]]>In their anthropological study of a tribe of scientists, Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar speak of the methodological problems involved with drawing conclusions from observation. A key component is the familiarity of the observer to the evidence being observed: “it is important that testing be carried out in isolation from the circumstances in which the observations were gathered,” they write. “On the other hand, it is argued that adequate descriptions can only result from an observer’s prolonged acquaintance with behavioral phenomena” (37). This is the essential difference between two schemes of validation, “favouring the deductive production of independently testable descriptions” (etic) versus “favouring the ‘emergence’ of phenomenologically informed descriptions of social behavior” (emic) (38). Ultimately they side with the emic, producing a document which describes the life of a laboratory in situ, but not without warning of the dangers of “going native,” that is, an “analysis of a tribe that is couched entirely in the concepts and language of the tribe” (38).

This seemed to me an essential concern not only for the observer-anthropologists, but for the scientists they are studying. Although Latour and Woolgar insist that they are describing social phenomenon, and thus producing something different than scientific facts, there is a definite tension about how and why to differentiate observer from participant. I began to wonder where the line between emic and etic began to break down, and the extent to which an observer has always-already “gone native” with respect to their observation. Since the emic/etic divide is essentially a question about description, one might look to how observations are produced by language. And since language is largely thought of as a social phenomenon (at least for literary scholars and anthropologists), the way it is observed by scientific analysis, that is, as a material effect produced by the brain and vocal organs, calls our validation schemes into question.

I thought it might be productive to use Latour and Woolgar to think about the emergence of thinking about language as a material and embodied process, as intimately connected to our brains and bodies as to culture and history. Interestingly enough, in the history of science, the moment at which the ‘fact’ of language begins to take hold is the moment it begins to break down. The identification of aphasia as a loss of ability to read or write, not caused by genetic deficit but by disease or wounding, challenged the notion that language was the seat of rationality or a direct extension of our cognitive abilities. Like Heidegger’s proverbial hammer: it is only when the hammer breaks, thus revealing a deficit, does it become apparent in its being. The shock of aphasic deficit displaces habitual models of perception, turning normative linguistic brain function into something strange. Medical inquiry usually begins with a realization of a negative capacity, and this is thoroughly present throughout the history of aphasia studies.

In 1783, Samuel Johnson suffered a mild stroke leaving him unable to speak for several weeks. During that time he provided an account of his condition in letters, detailing a paralysis in his ability for speech while his cognitive abilities remained intact. Being a religious man without a modern clinical vocabulary, Johnson attributes this loss of speech to spiritual intervention: “it hath pleased the almighty God this morning to deprive me of the powers of speech,” he writes to his doctor (Eagle 2).

Several decades later in 1866, Charles Baudelaire, living in exile in Brussels, falls into ill health and begins to experience aphasic symptoms that he struggles with until his death a year later. There are biographical records of confused patterns in Baudelaire’s speech, such as “asking his friends to open (rather than close) an already open window” and “saying ‘see you tonight’ (rather than ‘goodbye’) as they parted” (3). Baudelaire’s autopathographic description notably diverges from Johnson’s, as he writes in a letter to his mother that “you need to understand that writing my whole name now is a great task for my brain” (3).

Chris Eagle notes that what is interesting about these two letters is how they “illustrate a major paradigm shift which takes place in the decades between their strokes: from the traditional conception of language as a spiritual faculty to the modern view of language as a biological process rooted in the brain” (4). Between these two literary figures we see the historical implications of considering how the loss of proper speech functioning may be discontinuous with the faculty of language as a whole.

Of course, the progression that leads to Baudelaire’s self-diagnosis of his speech disorder is only the beginning of modern aphasiology; the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries are marked by the exploration and development of accounts of language that stem from materialist approaches to neurological functioning. In his study of the medical literature on aphasia in modernity, Lost Words: Narratives of Language and the Brain, 1825 – 1926, L. S. Jacyna states that “It is possible to assign an inception date to the literature on aphasia: 1861” (3). Jacyna is referring here to the early work of Paul Broca, who famously attributes the faculty of articulate language to the left frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex.

The assignation of a specific inception date for aphasiology is significant not only because it confirms the paradigm shift between Johnson and Baudelaire, but because it emphasizes modernity’s obsession with novelty, the sense of the ‘now’ brought about by scientific discoveries that allow progression from a less developed past. Although the neurolinguistic findings on aphasia develop over time, we can see how within a modernist framework individual case studies can have immediate epistemological purchase on problems as fundamental as the relationship between mind and body. Here we can identify something of the the kind of social factors that determine the construction scientific facts that Latour and Woolgar are interested in.

While there was some debate on the adequacy of Broca’s account of aphasia, by the mid 1860s the discussion shifted from the question of whether language had a localized function in the brain to how this function could be conceptualized. In order to clarify this question, Broca hypothesized three levels of language function: The “general language faculty” which refers to the ability to establish a relationship between an idea and a sign encompassing all forms of signification, the “faculty of articulated language” which involves the conversion of ideas into speech through “emission or reception,” and the “voluntary organs” such as “the larynx, the tongue, the soft palate [voile du palais], the face, the upper limbs, etc.” (web).

Antonio Damasio writes “the true hallmark of Broca’s aphasia is agrammatism, a defect characterized by the inability to organize words in such a way that sentences follow grammatical rules and by the improper use of nonuse of grammatical morphemes” (532), for example, “utterances such as ‘Go I home tomorrow’ instead of ‘I will go home tomorrow’” (533).

Although more sophisticated accounts of neurolinguistic functioning build upon Broca’s formulation, I refer to his 1861 paper because it marks the emergence of thinking about the articulation of speech as a faculty apart from both physiological and cognitive conditions. Broca writes that “There are cases where the general language faculty persists unaltered, where the auditory apparatus is intact, where all the muscles, not even excepting those of the voice and those of articulation, obey the will, and yet where a cerebral lesion abolishes articulated language” (web), a special condition he terms aphemia.

It should be noted this famous presentation of aphemia wasn’t Broca’s primary objective at the time. It was part of a case study he presented at a symposium at the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris on the question of whether there was a causative relationship between the mass of an individual’s brain and their intelligence (for which he interestingly cites the autopsy of Lord Byron as evidence) (Jacyna 69). Broca then, can be evaluated not only as a significant historical figure, but also as a case study for the kind of reductive materialist impulse that posits an inherent and totalizing link between the faculties of personality, reason, and intellect to physical and localized neurological conditions.

Although Broca’s model was amended and updated, the view that a very specific, circumscribed area that functions as the seat of language remained dominant for multiple decades. In an 1889 survey of cerebral localization in aphasia, the American neurologist Dr. M. Allen Starr defines three “epochs” in the history of aphasiology. The first of these was Broca’s, and the second occurs with Carl Wernicke’s distinction between motor and sensory aphasia in 1874. Damasio describes patients with Wernicke’s aphasia a “[having] no difficulty producing individual sounds, but they often shift the order of individual sounds and sound clusters and can add or subtract them in a way that distorts the phonemic plan of an intended word; for example, they may say trable instead of table” (534).

In other words, observing a difficulty in word production that is unrelated to motor defects allows Wernicke to hypothesize these as separate functions. The third epoch is inaugurated in 1883 with Jean-Martin Charcot’s call for a more refined account of sensory memory in which both spoken and written language interact (330-1). Charcot’s model views the word as a “complexus” in which one can discover “four distinct elements; the auditory memory picture […], the visual memory picture […], and also two motor elements, the motor memory of articulation and the motor memory of writing; the first developed by the repetition of movements of the tongue and lips necessary to pronounce a word; the second by the practice of motions of the hand and fingers necessary for writing” (331). Although Charcot’s descriptive terms would certainly not be accepted by neuroscientists today, it is the first step toward a more integrative, embodied approach to cognition and memory in which the movement of the hand is intimately connected to the articulation of language.

In giving this account of the history of aphasia studies, I don’t mean to say that we should group language in with other bodily occurrences such as digestion. In fact, I’d like to combat forms of ‘bad materialism’ that reduce everything to physical processes. But if we are to state anything about language as a ‘fact,’ it must therefore be situated somewhere between social and embodied articulations. Also, as we see in the surprisingly late realization of language production as a faculty apart from comprehension, the production of scientific knowledge is inseparable from its social situation. I think Latour and Woolgar would agree.

Works Cited:

Broca, Paul. “Remarks on the Seat of the Faculty of Articulated Language,Following an Observation of Aphemia (Loss of Speech)” Bulletin de la Société Anatomique, 6, 330-357. 1861. Web.

Damasio. “Aphasia.” New England Journal of Medicine. 326.8 (1992).

Eagle, Chris. Dysfluencies: On Speech Disorders in Modern Literature. New York: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Jacyna, L. S. Lost Words: Narratives of Language and the Brain 1825 – 1926. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000

Latour, Bruno and Woolgar, Steve. Laboratory Life: the Construction of Scientific Facts. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979.

Malabou, Catherine. Ontology of the Accident: An Essay on Destructive Plasticity. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012.

Salisbury, Laura. “Sounds of Silence: Aphasiology and the Subject of Modernity.” Neurology and Modernity: A Cultural History of Nervous Systems, 1800-1950. Ed. Salisbury, Laura and Shail, Andrew. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010

Starr, M. Allen. “Discussion of Cerebral Localization: Aphasia.” Transactions of American Physicians and Surgeons. New Haven: The Congress, 1889.

The post Between Language and Materiality: the History of Aphasia Studies appeared first on &.

]]>An analysis of scientific tools using the theory of cultural technique to understand how they structure social relations within a network.

The post Genome Browsers: The Book of Life Isn’t Open Access appeared first on &.

]]>If I can access the human genome, does that make me a scientist? An analysis of scientific tools using the theory of cultural technique to understand how they structure social relations within a network.

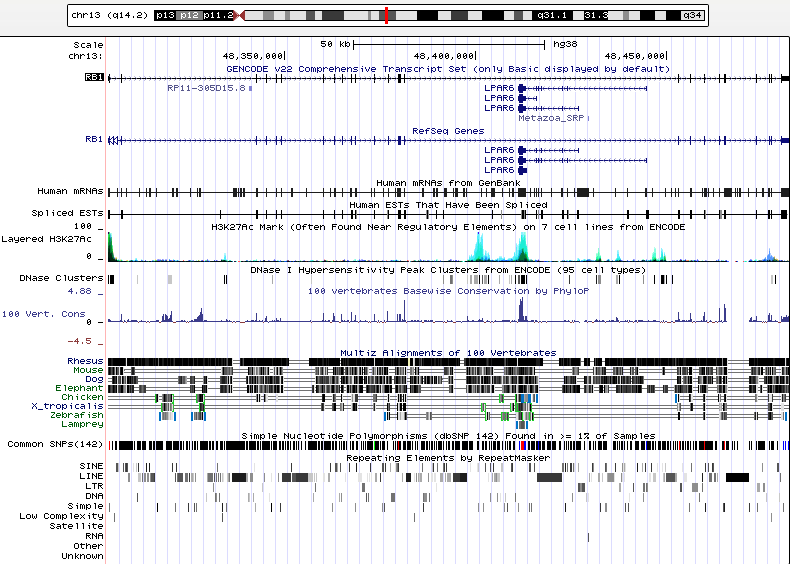

Bioinformatics: A Technique Developed to Produce Knowledge

Science is a highly dynamic field of knowledge production. Every so often new technologies emerge that change the conditions necessary to produce knowledge and allow for great advances in our collective understanding. When the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium (IHGS) published the first of the human reference genome in 2001, they fundamentally changed the field of biology. Through the comprehensive assemblage (map) they produced, scientists were able to demonstrate that the human genome contains only around 20,500 genes, which was much lower than the estimated 60,000 to 140,000 genes (NIH 2015). This meant that contrary to scientific belief, genes were not the source of organismal complexity. This realization forced them to consider that the key to “the Book of Life” might not lie in the genes themselves, but in what was referred to as “junk” DNA, the highly repetitive non-coding sequences of the human genome. In just a few years, the focus of genetic research shifted away from identifying genes to determining the elements that influence gene expression (the epigenome, the proteome, protein modifications, siRNA and other non-coding DNA elements).

As fundamental as this realization was for scientists, the completion of the Human Genome Project would not have been possible without computational analysis. In 1990, when scientists first attempted to sequence the genome in full, they were still using the laborious technique of cloning small sections of genetic code and inserting them into bacterial life forms. At the time, it was only possible to sequence short stretches of DNA using analogic methods. In order to sequence the three billion base pairs of the entire genome, it was necessary to use other techniques. While the project was publicly funded, it wasn’t until Celera, a private company, involved itself in the race for the human genome that computational analysis was used in sequencing techniques. Celera’s CEO, Craig Venter, had invented a new technique of DNA sequencing called “whole genome shotgun sequencing” that sequenced fragments of the entire genome simultaneously and used bioinformatics to reconstruct the sequence. While other sequencing technologies have since been developed, bioinformatics has remained central to the process of data assemblage and analysis.

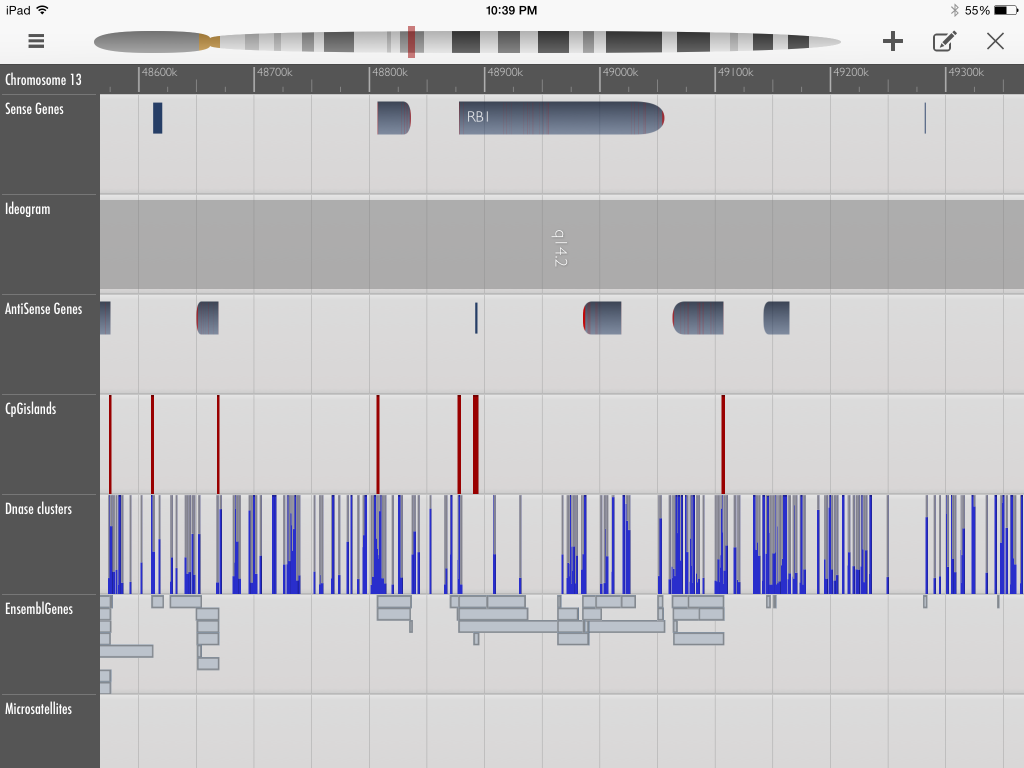

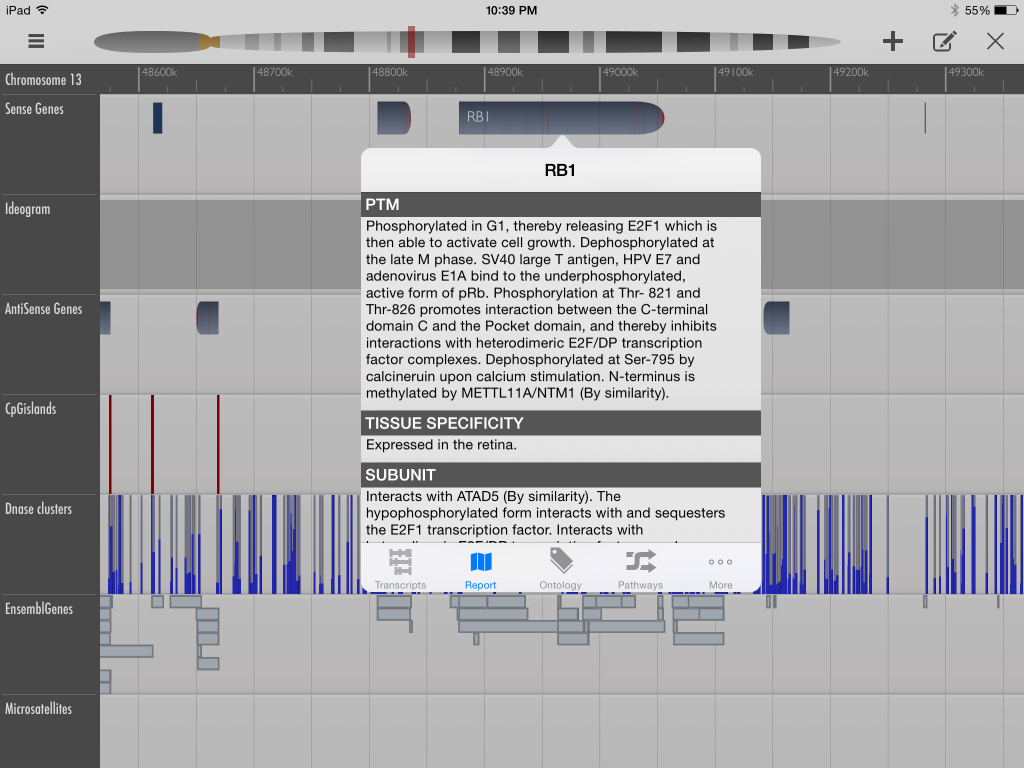

Since the entire draft of the human genome was published in Nature over ten years ago, app developers have continued to produce platforms that enable users to browse the entire human genome free of charge. Genome browsers “intertextualize” assemblages of the human genome by displaying the different assemblages on tracks that can be configured by the end user. As a product of bioinformatics and the digital age of information sharing, genome browsers allow users to search the genome using gene location and map coordinates and to import their own sequences to compare their objects of study with previously identified genetic elements and their known functions. The use of genome browsers to analyze biological data has become a central practice of molecular biologists in identifying new genes and biological mechanisms.

The Cultural Technique of Genome Browsers: A Question of Accessibility

One way to consider how scientific tools shape social practice, according to the German theories of cultural technique, is to consider the history and development of the object as I have done. Genome browsers were developed in the wake of the Human Genome Project as a method of data analysis. Because of this, discourses of accessibility that emerged during genome mapping are applicable to processes that analyze the maps.

“Essentially, cultural techniques are conceived as operative chains that precede the media concepts they generate.” (Siegert 58)

Discourses of universal accessibility to the information produced by the publicly-funded project were strengthened by the UNESCO declaration in 1997 on the Human Genome and Human Rights. In a press release in 2001, the phrase “The information has been given away freely to the world—a vast and unique gift to celebrate the commonality of humankind” was used by the Sanger Institute, one of the 16 centres that formed the IHGS (Thomson 2001). In 1999, a scientist discussing the Human Genome Project within the context of a course wrote “To be valuable to society, genetic information must be available to all people in need of such information” (Boehm 1999).

In the same vein, the genome browser developed by the University of California-Santa Cruz (UCSC genome browser, 2002) is freely accessible online for educational purposes, and apps like GeneWall developed by Wobblebase, Inc. (2015) and Human Genome by Florence Haseltine (2012) are free to download. But is access the same as accessibility?

These genome browsers come in two flavors: research-oriented, like the UCSC genome browser, and user-friendly, like GeneWall. While these platforms are structurally similar, there are important differences in their infrastructure that determine their intended audience and user accessibility to database information.

The UCSC genome browser (pictured above) was developed much earlier than GeneWall’s and is the interface of choice in molecular biology labs. The interface’s native settings allows users to view a region on the genome that spans 26 assemblage tracks. The website allows sequence search and comparison (through tools BLAT) and allow users to navigate and customize the viewing of assembly sequences, mRNA transcripts and other organisms easily and quickly. However, navigating the database is complicated by the lack of explanation and presupposes users have a certain degree of biological literacy.

I have described GeneWall as more “user-friendly” because its interface, the iPad, allows users to navigate the assemblages using finger-swipe gestures. With a minimalist and uncluttered design, the descriptive elements for genes and other DNA elements are accessible by tapping on their mapped position. However, the system is in its infancy and is not as well connected to other tools like the UCSC browser. Another limitation of GeneWall is that its structure is centred around already a limited number of sequenced genes with determined functions, as opposed to displaying an array of mapped assemblages to allow users to infer the structure of the mapped region through juxtaposed elements. This user-friendly system also places limitations on the user’s potential production of scientific knowledge by focusing on the biological questions of the Human Genome Project era.

The Cultural Technique of Genome Browsers: A Tool to Limit User Access

These objects are structured to act as “gate-keepers” for scientific knowledge. By limiting the object’s users to “those with biological training” or limiting their databases to established forms of knowledge, developers of genome browsers are restricting the field that produces scientific knowledge. In this sense, the gatekeeping activity of these platforms confers authority to those with scientific training. In “The Growth of Medical Authority,” Paul Starr describes gatekeeping as the basis for professionalization: “The basis of modern professionalism has to be reconstructed around the claim to technical competence, gained through standardized training and evaluation” (475). This is made clear when you consider the access to content in MyGenome, developed by Illumina, a private biotech company: users are readily provided with an example genome, but Illumina will only release their personal sequence to the ordering physician. Despite all the rhetoric of the genome as human heritage that should be readily available, the truth is you can’t access your own genome until it’s been explained to you.

“Technologies are associated with habits and practices, sometimes crystallizing them and sometimes promoting them. They are structured by human practices so that they may in turn promote human practices.” (Sterne 376)

When I began reading media articles written by developers, I realized that they were defining access around infrastructures rather than the information they contain. They view genomics as a “niche product in large part used in and promoted by academia” (Kaganovich 2015) and instead are interested in developing “a wide variety of health and well-being apps and platforms that will be able to do things like connect variants to environmental, lifestyle, dietary, and activity-related factors, guiding both sick and healthy people towards a fundamental quality of life” (Menon 2015). Developers are interested in genomics that can be analyzed and marketed to the consumer without the need for the scientist. They see the future of genome browsers not as scientific tools but as gateways to personalized medicine.

Cultural Technique: A Method of Mapping the Actor-Network

Genome browsers were developed to allow users to access the human reference genome so that scientific knowledge would be advanced through data sharing. However, the limitations placed on users by the system infrastructures only allow users to interact with the information pre-determined by developers.

“When we speak of cultural techniques, therefore, we envisage a more or less complex actor network that comprises technological objects as well as the operative chains they are part of and that configure or constitute them.” (Siegert 58)

In this probe, in order to understand how genome browsers function as cultural techniques, I considered these tools within the context of their development to map the network of actors who interact with them. Actor-developers design these platforms with structures that control and limit the end-users’ possible interactions. This limiting aspect, that I have examined under the guise of “access” and “accessibility,” lends authority to a restricted group of end users who are able to obtain the platform’s information. This example illustrates the mechanisms of a cycle of knowledge production, within which objects are shaped by agent-developers to perform certain cultural actions and in turn shape agent-users by limiting access to information.

Works Cited

Boehm, David. “Applications and Issues of the Human Genome Project.” Plsc 431/631 Intermediate Genetics, ndsu.edu. web. 1999.

Kaganovich, Mark. “Genomics Needs a Killer App.” Crunch Network, techcrunch.com. web. March 27, 2015.

Menon, Prakash. “Coming Soon: An API for the human genome.” Health, venturebeat.com. web. June 27, 2015.

NIH. “An Overview of the Human Genome Project.” National Human Genome Research Institute. web. June 29, 2015.

Siegert, Bernhard. “Cultural Techniques: Or the End of the Intellectual Postwar Era in German Media Theory.” Theory, Culture & Society 30(6) 2013: 48-65.

Starr, Paul. “The Growth of Medical Authority.” Perspectives in Medical Sociology, 4th edition. Ed. Brown P. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, pp. 475-482.

Sterne, Jonathan. “Bourdieu, Technique and Technology.” Cultural Studies 17(3/4) 2003: 367-389.

Thomson, Mark. “The first draft of the Book of Humankind has been read.” Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, sanger.ac.uk. web. June 26, 2001.

The post Genome Browsers: The Book of Life Isn’t Open Access appeared first on &.

]]>The post The Photograph and the Monk or the Monk and the Photograph appeared first on &.

]]>Preamble to the Probe

On Stories

Everything in life can be told as a story. We live our lives serving willingly or unwillingly as protagonists of our and others’ stories, unbeknownst to us that even in the most mundane of acts, such as drinking our morning coffee, for example, we are passive or active participants, in various degrees and forms, in endless stories, tales, the totality of which we like to call life. And since I have mentioned drinking one’s morning coffee as an example, in the drinking of it we partake in writing the story of the cup which holds the coffee, of the coffee beans that were needed to produce it, of the water that was used to brew it, of the sugar that sweetened it, and of the money which officiated the transaction permitting the transfer of ownership of the coffee from the one who produced it to the one drinking it. Everything can be seen as part of an infinite number of clusters of stories, simultaneously being written, told, noticed or unknown to us for lack of interest or ability to simply observe, know and understand everything.

This interconnection between the human and the non-human, explained convincingly by the actor-network theory[1], is the focus of my present probe. Unlike other writings I have done thus far, in this one, I explore the power of nonhuman agency[2] to affect change, seeing the human and the non-human as both alive, crafting each other’s fate.

The title of my story is ‘The photograph and the monk or the monk and the photograph.’ I want to ensure that at no time the human becomes this story’s main character. But even this title does not do justice, as what I am about to tell is not just about a photograph and its owner. Ultimately, it is about power and about adjustments or resistance to power, about what the French thinker Michel de Certeau called “strategy” and “tactics.”[3] Lastly, my story is about practices[4] concerning the handling of an object—a photograph—and how its meaning evolves as a result of changes of its circumstances over time. It is my hope that it, this story, sheds light on the intricate nature of life, any life, of humans and non-humans, all co-participants in never-ending tales.

The Probe: The Photograph and the Monk or the Monk and the Photograph

Questions

I approach the idea of writing about the photograph above with several key questions in mind: how closely related is the meaning of a given object to its medium or environment? If it has multiple meanings, is there one that overshadows the rest? In other words, does a simple wallet-sized photograph like the one presented here undergo metamorphosis and, if it does, and it becomes something else, can it ever return to its original state of being solely a photograph? Or, does it carry behind its story— the various meanings it accumulated over time?

The photograph and I, Bucharest 2014: surprise and excitement

To attempt to answer these questions, I must being my own story: It all began in Bucharest, Romania, in 2014, in one sunny May day spent at the Council for the Securitate Archives (ANCSAS), the institution which now handles the archives of the secrete police (Securitate in Romanian) files from Romania’s communist era (1945-89). On that day, I was examining my great-uncle Securitate files from the late 1940s until mid 1960s. His name was Antonie Plamadeala and the time mentioned here, he was a Christian Orthodox monk. The files were about Securitate’s surveillance of Plamadeala in 1940s-1950s, his incarceration years as a political prisoner (1954-1956) and Securitate’s surveillance of Plamadeala after his release from prison.

Going through thirteen dossiers pertaining to him, roughly 2000 pages, mostly typed but a few hand written, was not an easy task. Reading these dossiers requires patience and a great deal of intuition in discerning truth from lies, facts from misleading information aiming to camouflage truth. For example, a document confirming one’s death from tuberculosis may have meant, in reality, that the person the document is concerned with died as a result of physical torture received during prison interrogations. On that specific day, I stumbled upon several documents alluding to some degree of torture. Needless to explain, my own experience with the files was filled with emotions of my own. However, when I saw this photograph, carefully placed in of these dossiers, I was taken by surprise. True, at first this picture may look troublesome. Entitled Nebunul (the Crazy Man), it represents a man in a huge pile of human bones. He is raising an undecipherable item, in a somewhat victorious pose. There is, however, something powerful about this picture. At least to me, it seems to convey a sense of tenacity, ability to endure, to persevere, to go on against all odds. On the back of this photograph, one can see my uncle’s handwriting: Passini pe un morman de cadavre (Passini on a pile of cadavers), signed with his first name Leonida, the name he had prior to his becoming a monk in 1949, and dated as April 1948, Bucharest. Seeing this photograph for the first time brought me back to my first perusal of Plato’s Republic and my introduction to his allegory of the cave. This man, in the photograph, was not crazy at all, I concluded. He simply refused to succumb to darkness. His refusal to accept his status quo was perceived as madness.

But there is more to this photography than my sense of excitement with it. Who was I to define it? A mere observer, overwhelmed by the immensity of information in those files and excited to find something unusual in them? And so I wondered what others saw in it? For that, I went back in time, back to April 1948.

The Photograph and the Monk, Romania 1940s: hope

It is safe to assume that my uncle was once the possessor of this photograph, as it was confiscated by Securitate from his room, sometimes in the 1950s, after his release from prison. About this, I elaborate at greater length in the next section. Now, however, I intend to explore my uncle’s relationship with this photograph in the 1940s. For that, I must call upon historical accounts to uncover the truth. What was happening in April 1948 in Bucharest? And more importantly, what was taking place in Plamadeala’s life in that month? The latter question is more difficult to answer, given the mystery that surrounds any human life and the impossibility to articulate fully in words about one’s state of existence, tangible and intangible, the latter being defined by one’s thoughts, emotions, hopes and aspirations.

By April 1948, only four months had passed from the establishment of the communist regime in Romania. This war-torn country was at that time facing dramatic socio-economic and political changes as a result of the coming in power of the Communist Party. Anyone involved in anti-communist resistance was being arrested or hunted by Securitate. The Orthodox Church was among the government’s main targets; the youth was as well, as its restlessness, idealism, courage and audacity to think that it can change life for the better are always menacing to dictatorial regimes.

My uncle happened to have embodied all that: in April 1948, he was young (22 years old), a theology student, and a fervent anti-communist, having served as an editor and writer of a clandestine newspaper (Ecoul Basarabiei/The Echo of Bessarabia), that encouraged its readers to fight for the liberation of a former Romanian region (Bessarabia) from the Soviet occupation. Having been born in Bessarabia, the involvement in the writing of this newspaper was rather personal for Plamadeala.

In April 1948, Plamadeala was on the run from the Securitate seeking to arrest him for his involvement in the anti-communist resistance. By then, he was hiding in various monasteries, churches, and basements of friends’ houses. One can only imagine what was life like for him at that time. This picture, however, may give us a hint of the tenacity of this young man who was refusing to surrender to the communist secret police. This photograph, I think, may have served for Plamadeala as constant reminder to not lose hope.

The Photograph and the Securitate, Romania 1950s: intimidation

After six years on the run from the Securitate, Plamadeala was eventually arrested and imprisoned at Jilava prison in October of 1954. He would remain incarcerated there for two years and released in April of 1956. Shortly after, he was defrocked, stripped of his academic credentials, and ostracized from society, left in the mercy of his family on the streets of Bucharest. In the late 1950s-early 1960s, he was employed as an unqualified worker in a plant in the suburbs of Bucharest. It was around this time that this picture was confiscated by a Securitate officer and placed in Plamadeala’s dossier.

This picture came to Securitate’s attention most likely for its relation to Plamadeala’s writings. By then, the Securitate knew from its informers that he was writing at nights, after his day-time work in the plant, a novel which intended to criticize harshly dictatorial regimes and the way human beings are psychologically affected by the lack of freedom such a regime installs in the people it governs. Any nuanced reader would have seen the manuscript’s connection to the events taking place in Romania at that time.

Writing may have been an expression of resistance for Plamadeala, resistance via nonviolence. In the end, Plamadeala concluded that even this method of resistance may be powerless, as he wrote the following in the final chapters of his manuscript: “what can, let’s say, the unarmed Kant do while facing a hungry lion?”[5] Still, the “unarmed Kant” in Plamadeala felt somewhat hopeful that eventually his voice and story would be heard. This one learns from a Securitate report written on him, where agent “Grigorescu Marin,” a false name of a then pretended friend of Plamadeala who was secretly spying on him, wrote that Plamadeala hoped the manuscript “would be a novel of the era.”[6]

As Plamadeala hoped, his manuscript did eventually turn into a novel, and a great one. Trei Ceasuri in Iad (Three Hours in Hell), for its literary eloquence, depth and simplicity, became one of Plamadeala’s most known works. This book describes people who suffer from some form or another of depersonalization, manifested by their inability and fear to express overtly what they think and feel within— a crisis of the soul, of one’s essence. Incidentally, the only character of the book who does exercise his freedom of expression and is not punished by the police and society is Karl, deemed by the rest as demented or crazy for his eccentricity. It is very possible, therefore, that the Securitate confiscated this photograph because of its link to the writing of this manuscript. By confiscating it, the secrete police was probably attempting to install fear in Plamadeala and intimidate him from writing his book.

The Photograph and ACNSAS now: relic from the past

Years have passed. Communism fell in Romania as it fell in the rest of the former Soviet bloc. And yet, its presence is still felt; the residue of this country’s communist past is still noticeable and pondered upon by many, including myself. The photograph is no longer a symbol of hope, resistance, or an instrument of intimidation. It is a relic from the past, a reminder of how life was for others, an item which we now can call an ‘element of history’, helpful in writing history down in decipherable words.

The Photograph and our course, Montreal 2015: object of reflection

But what does this photograph mean in this very moment? To me, it is an object of reflection. I still am trying to decipher its meaning. Who was Passini, the man mentioned in the back of this photograph? Who wrote the title of this photograph—Nebunul? And who wrote the lower two inscriptions, which seem to be written in a cryptic format, backwards: MUAR/INISSAP RODIROLF. There is a great deal of mystery attached to this photograph, which story somehow managed to involve me, my computer employed to write it, and, now, our course. Everything in life can be written as a story… Is writing a story a story in itself?

References

ACNSAS, fond operativ, dossier 1015, p. 80 (the photograph).

[1] John Law. “Notes on the Theory of the Actor-Network: Ordering Strategy and Heterogeneity,” in Systems Practice, 5 (1992), 379-93.

[2] This concept is employed in light of the article written by Andrew Pickering. “The Mangle of Practice: Agency and Emergency in the Sociology of Science” in The American Journal of Sociology, 99 (3), 559-589.

[3] These concepts are employed in light of the article written by Michel De Certeau. “On the Oppositional Practices of Everyday Life.” Social Text 3 (1980), 3-43.

[4] This concept is employed in light of the article of Helga Wild. “Practice and the Theory of Practice. Rereading Certeau’s ‘Practice of Everyday Life’” in JBA Review Essay (2012): 1-19.

[5] Antonie Plamadeala, Trei Ceasuri in Iad [Three Hours in Hell] (Bucharest, Editura Sophia, 2013), 9.

[6] Ibid, 8.

The post The Photograph and the Monk or the Monk and the Photograph appeared first on &.

]]>The post Probe: Actor-Discourse-Network-Economy appeared first on &.

]]>In his book Aufschreibesysteme 1800/1900 (1985) – Discourse Networks 1800/1900 (1990) – Friedrich A. Kittler brought discourse analysis to media studies, coining discourse network to “also designate the network of technologies and institutions that allow a given culture to select, store, and process relevant data” (qtd. Liu 50n4). Reformulated as such, discourse gains direction, speed, and technological articulation. In Kittler’s discourse network circa 1900, the typewriter becomes a “discourse machine gun” (Kittler 14; cf. 191), and in Alan Liu’s “discourse network [circa] 2000″, Web 2.0 becomes a kind of discourse superlaser-armed drone-network of “phenomenally senseless automatism” (Liu 81) – a conviction anticipated by Kittler in his subsequent book’s ultimate epitaph for hermeneutics: “Under the conditions of high technology, literature has nothing more to say. It ends in cryptograms that defy interpretation and only permit interception…. By its own account, the NSA [National Security Agency] has ‘accelerated’ the ‘advent of the computer age,’ and hence the end of history…. An automated discourse analysis has taken command” (263).

It is in view of this acceleration that contributors to the latest issue of Amodern proportionally urge us to caution. The introducers write:

[N]etwork temporality is often described in terms of acceleration to the point where time is eviscerated as a historical dimension.Paul Virilio warns us of the “dictatorship” of speed that accompanies the development of information networks, which threatens to reduce our rich histories by locking us into a global, universal time – what Castells describes as a “timeless time.”This temporal logic is seen as “instantaneous rather than durational and causal” and “simultaneous rather than sequential,” constituted in relation to immediate crises. The network is understood as ever-present, real-time, a structure that flattens rather than historicizes. (Starosielski, Soderman, and cheek np)

Similarly, Alan Liu in the interview by Scott Pound:

Spatial-political barriers that once took muscular civilizations centuries, if not millennia, to traverse by pushing through roads, etc., are now overleaped in milliseconds by a single finger pushing ‘send.’ The temporality of shared culture is thus no longer experienced as unfolding narration but instead as ‘real time’ media. Specifically, the old phenomenology of store-and-forward temporality transforms into the new ideal of instantaneous/simultaneous temporality – a kind of quantum social wavefront connecting everyone to everyone in a single, shared now. (Pound and Liu np)

In short, we musn’t eschatologize Kittler’s “end of history”-by-automation into a Fukuyaman panegyric on neoliberalism’s millenial prosperity. We must, rather, as with all else continue to “situate networks in time,” historicizing and finding new ways to represent temporal relations within networks themselves: a “network archaeology” (Starosielski, Soderman, and cheek np). For “[n]etworks are processual and not just a stable diagram of nodes connected” (Pound and Liu np).

It’s unconditional (according to discourse theory itself, of course) that a theory that “flattens” history is part-and-parcel of the archaeologized historical conditions it describes as history’s flattening. My probing, then: What can a historicizing of discourse-networks (despite their self-necessitating archaeo-historical pseudo-retroactive arche of universality), or rather, what can archaeologizing the emergence of discourse-network theory in the episteme of the “network society”, tell us about the neoliberal discursive formations around which such a theory emerged (i.e. archaeo-emerges)?

The “dictatorship of speed” articulated above to the atemporal character of actor-discourse-networks is the dictatorship of neoliberal capital flow. The “rational”-subject-oriented neoliberal’s wet dream is perfect frictionlessness to maximize the exchange of money and goods. Like all dreams – a desire for the non-existent transcendence beyond an insurpassable asymptote – this is necessarily eschatological, as optimally distance and time reduce to two noughts ratio-nalizing speed into an ineffable division (speed = d/t). Since “people are being treated only as investments […,] [t]he future is ‘just the future’ – and it’s discounted at compounded annual rates” (Zuesse np).

In this context, I’d like to focus specifically on the “discourse” component of the actor-discourse-network, and its relation to speed and capital. In two 1980s essays, critic and poet Steve McCaffery, following the economic linguistic metaphors of Barthes, Derrida, and Bataille, and informed by Lacanian and Kristevan psychoanalysis, approaches language as a general economy. Flattening language into a material “surface” or “surface play” (“Language Writing” 149, 151), McCaffery makes the anti-hermeneutic discursive assessment that “[l]anguage today no longer poses problems of meaning but practical issues of use” (148). The conventional notion of language as a transparent vessel for a transcendent content, for example, assumes a certain use for it, based around the efficiency and efficacy of content transmission in the old “model of communication as a transmission-reception by two individual, reflective consciousnesses” (156). In such a model,

Deleuze and Guattari’s descri[ption of] the State as “the transcendent law that governs fragments”…applies equally to grammatical as to political control. As a transcendent law, grammar acts as a mechanism that regulates the free circulation of meaning, organizing the fragmentary and local into compound, totalized wholes…. Like capital (its economic counterpart) grammar extends a law of value to new objects by a process of totalization, reducing the free play of the fragments to the status of delimited, organizing parts within an intended larger whole…. [G]rammar effects a meaning whose form is that of a surplus value generated by an aggregated group of working parts for immediate investment into an extending chain of meaning…[,] homologiz[ing] the capitalistic concern for accumulation, profit[,] and investment in a future goal. (“Language Writing” 151)