The post Probe: Talking Trees appeared first on &.

]]>Probe for Nov. 7

Given the extent to which tree structures have permeated computer science (think of the way the files are organized on a computer, or the nested windows and menus used in software applications), it’s no surprise that we find them everywhere in digital games. Some appear in the form of tree diagrams, others are hidden or disguised. Not all of these trees are “true” trees, according to the strict definition of the word as outlined in graph theory, but the very fact that we call them by this name suggests that these mutants occupy at least some of the same conceptual terrain as their undirected, non-cyclical sisters.

One of the most interesting examples of trees I’ve encountered in games so far is the realm tree in Crusader Kings II, which provides players with a visualization of the feudal hierarchy that is so essential to the game. The tree resembles an organizational chart, depicting the chain of command from emperors down to barons, mayors, and bishops (peasants don’t make the cut); it also, importantly, indicates their opinion of your character, and your character’s opinion of them (the green or red numbers by their portraits), as well as what percentage of the realm’s total troops they control.

Screenshot of the realm tree from Crusader Kings II. My character is Zegota, at the top or root of the tree.

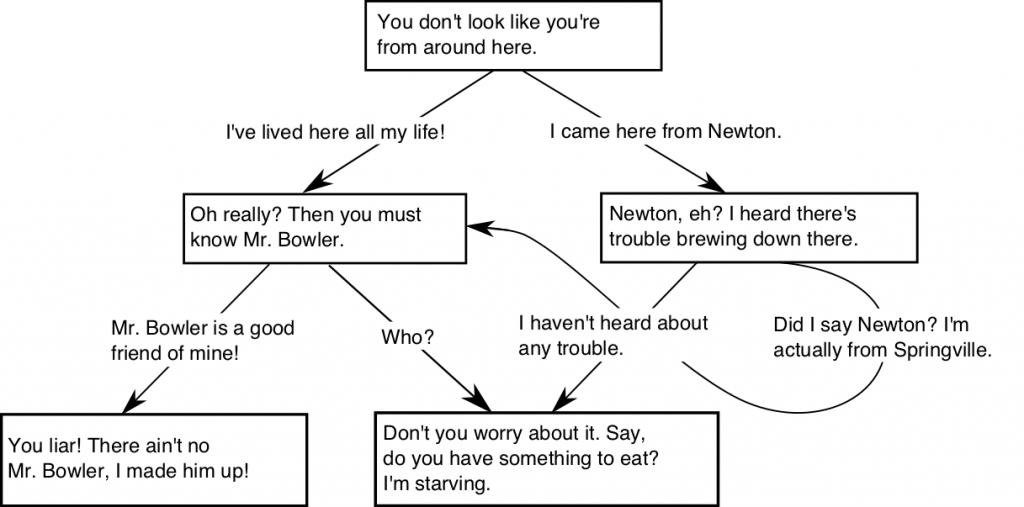

Other trees are much less visibly “tree-like” than this one however, at least from the point of view of the player. For example, one of the staples of digital role-playing games and adventure games is the so-called dialogue or conversation tree.

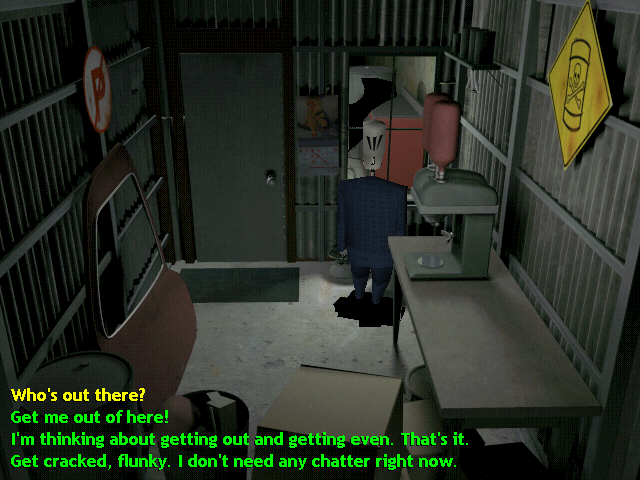

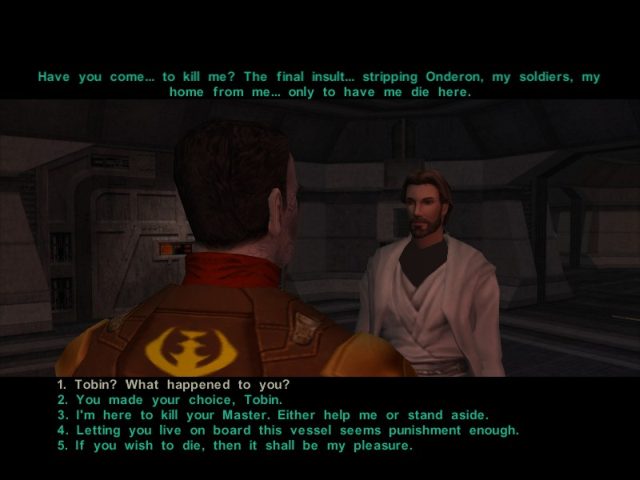

The term refers to the branching structure employed in games such as Dragon Age: Origins, the Walking Dead series, and Grim Fandango. However during conversations the branches (the links connecting parent nodes to child nodes) are invisible to players, who are instead confronted with a list of options indicating potential responses. Selecting one of these options leads to another list of responses, which leads to another, and so on, until the conversation comes to an end.

For some players even a limited number of choices can impart a sense of agency or individuality, enhancing moral or emotional investment in the game by allowing them some say in how the story unfolds—or at least that’s the idea. For developers, however, structuring dialogue in this way can also be extremely labour-intensive, particularly if each response is fully animated and voice-acted. Constraints such as budgets and fixed release dates often force developers to merge branches together so that different choices lead to the same outcome or event. As a result typical dialogue trees are much more akin to Alfred Kroeber’s tree of human culture, with its multiple points of convergence, than they are to the ever-diverging tree of life (Moretti).

In an effort to reduce the scope of the game developers may also restrict the number of options available at each juncture to a set of “logical” or “expected” choices. In many cases these choices seem to be constructed with a particular audience in mind. They may also reflect the personal biases of the developers. For instance, in the games that I’ve played, moral choices often consist of deciding whether or not to kill a character (or which character to kill), and the option to give an object appears much less often than the option to receive.

In an effort to reduce the scope of the game developers may also restrict the number of options available at each juncture to a set of “logical” or “expected” choices. In many cases these choices seem to be constructed with a particular audience in mind. They may also reflect the personal biases of the developers. For instance, in the games that I’ve played, moral choices often consist of deciding whether or not to kill a character (or which character to kill), and the option to give an object appears much less often than the option to receive.

While the trees examined by Franco Moretti are figured as representations or tools that help us to make sense of the past (and to some extent the present), dialogue trees are more clearly oriented towards the future. They are not only descriptive, but also prescriptive, both in the sense that they can be used to guide the development of a game, and in that when implemented, they restrict the field of possibilities within a game to a selection of relatively fixed options. Jacob Harley argues that, “the steps in making a map – selection, omission, simplification, classification, the creation of hierarchies, and ‘symbolization’ – are all inherently rhetorical” (11), a statement that might just as easily be applied to trees. As organizational structures articulated through diagrams and code, dialogue trees are part of the matrix of explicit and implicit rules that determine what can be done and what can be said within the space of a game. As such their disconnections and exclusions interest me as much as what they make visible or possible.

These positive and negative spaces only really begin to take shape, however, when we look at large numbers of dialogue trees, rather than focusing on individual examples. Just because one game doesn’t allow the player character to directly engage in same-sex relationships does not mean that this game, or any other like it, is necessarily heteronormative. But when the vast majority of videogames omit this option, when as a whole they refuse to acknowledge even the possibility of anything other than heterosexual desire, then we can begin to talk about heteronormativity as a process of systematic exclusion, discrimination, and normalization.

At least some of the negative spaces will occur as a result of technological limitations, and understanding where these limitations arise is no less important to our comprehension of dialogue trees than are the images or words on the screen. There are many reasons why developers have continued to represent dialogue as a series of multiple-choice questions, despite all the advancements that have been made in other areas (Sinclair). If dialogue trees are a matter of determining what leads to what, of setting up causal relations, then perhaps we should apply this logic to the trees themselves by asking what factors contributed to the widespread, persistent use of dialogue trees in certain genres. From there we can start to ask questions about how dialogue trees relate to particular notions of choice and agency in, for example, consumer culture and multi-party democracies. What does it mean to operate within a system that reduces choice to a list of several pre-determined options? Does it matter if the difference between options is only superficial? How do players resist, escape, or subvert such a system? What roles do imagination and representation play? How do dialogue trees relate (or not) to other structures and mechanics within a game? How is power distributed and enacted? Of course I have no answers to these questions, but then this is just a beginning, one among many.

Works Cited

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History.” New Left Review 28 (Jul-Aug 2004): 43-63. PDF.

Harley, Jacob. “Deconstructing the Map.” Cartographica 26.2 (summer 2919): 1-20. PDF.

Sinclair, Brendan. “Taking an axe to dialogue trees.” Gamespot, Oct 5, 2010. Web. http://www.gamespot.com/articles/taking-an-axe-to-dialogue-trees/1100-6280781/

The post Probe: Talking Trees appeared first on &.

]]>