The post Reading series/reading sound: a phonotextual analysis of the SpokenWeb digital archive (Al Flamenco, Aurelio Meza, Lee Hannigan) appeared first on &.

]]>The Reading Series

In the past twenty or so years, a large number of poetry sound recordings have been collected and stored in online databases hosted by university institutions. The SpokenWeb digital archive is one such collection. Housed at Concordia University, SpokenWeb features over 89 sound recordings from a poetry reading series that took place at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia) between 1966 and 1974. In the early 2000s, the original reel-to-reel tapes were converted to mp3, and by 2010 the SpokenWeb project, using the SGWU Poetry Series as a case study, was well into its exploration for ways to engage with poetry’s sound recordings as an object of literary analysis.

The collection’s ‘invisibility’ prior to its digitization (for over twenty years the original reel-to-reel tapes remained undiscovered, unreachable, forgotten, or deemed unimportant) is a glaring reminder of printed text’s monopoly in literary analysis and cultural production. Certainly, the written manuscripts of some of North America’s most important twentieth-century poets would not have collected dust for so many years, as did this collection of aural manuscripts — a collection which, as Murray and Wiercinski observe, “[draws] attention to the importance of sounded poetry for increased, complementary or even new critical engagement with poems, and . . . [disrupts] the marginalization of poetry recordings as a subject for serious literary research” (2012). However, before the SpokenWeb recordings became available in an online environment — before they became objects — they were an aggregate of inert documentary data — that is, a collection of archived materials (recordings, posters, newspaper write-ups) that together formed a unit of cultural production (reading series), shaped by bodies (organizers, audiences, poets), spaces (locales), and institutions (scholarly, poetic). Indeed, in order for a reading series to become a coherent object of literary study, its traces, what Camlot and Wershler call “documentary residue” (6), must be properly considered, for they are the constituents of meaning-making through which hermeneutic analyses of recorded audio filter. In other words, the SpokenWeb collection “urge[d] us to consider [the sound archive] as a result of social and technical processes, rather than outside them somehow” (Sterne 826).

As a coherent (if partial) unit of study, SpokenWeb, or the recorded reading series in general, allows us to return (if artificially) to an ephemeral live event, see beyond the archived document, and interpret it as an aggregate, one that is historically, technologically, and culturally specific. But how do we approach this aggregate? What might this particular phonotextual anthology tell us about modes of literary production in Canada in the late 60s and early 70s? How do we begin unpacking this data set? What does it mean to distant listen, or how do we read sound?

We began with an assumption, drawn from a recording of Robert Duncan’s 1965 lecture at the University of British Columbia, in which he speaks for over two hours, lecturing about poetry and poetics and reserving very little time for the reading of poetry in general, which seemed to oppose his claim of being a derivative poet.

Duncan, whose derivative poetic philosophy can be understood as a reincarnation of Romantic concepts of self-disintegration, highlights the inherently paradoxical nature of so many mid-20th century poetry readings — that is, existential consolidation of the poetic self through expository articulations of self-effacement. Which is to say, Duncan renounces the lyric “I” but uses a significant portion of his readings to talk about himself, a trend that proved true in his 1969 Poetry Series reading. This we determined by using the timestamps on Duncan’s recording to create a ratio between poems and extra-poetic speech. By extra-poetic speech we mean the content in the space between poems, where Duncan actually lectures about his poetry, provides anecdotes, or comments on his performance. Excluding George Bowering’s introduction, Duncan reads for two hours, six minutes and fifty-six seconds (another long session, by standard). For one hour and twenty-two minutes, he reads poetry. The remaining fifty-two minutes are filled with extra-poetic speech.

The balancing of poetry and poetics in Duncan’s reading led us to consider how other poets in the reading series might have organized their performance, and what that organization might reveal. For Duncan, it illustrated how aural performance can complicate poetic praxis. How do other poets organize their readings? Are there patterns to suggest that particular schools of poetry favour a certain structure of performance? Do poets begin readings with shorter poems, to ‘warm up’ their audience, and read longer poems in the middle? Do men read differently than women? Is there a relationship between venue and performance? Date? Time? Audience? The SGWU Poetry Series spanned nine years — would there be any recognizable changes in these patterns over that period? It became evident that the aggregation of reading series data could potentially reveal the social, historical, and cultural contexts that shaped the reading series, and also the underlying ideological structures within which the series took place. However, this information is difficult to access because the tools through which we attempt to do so are opaque (temporally, medially) and biased (i.e.who gets recorded, when, where and why). The reading series’ transcripts, it turned out, were a rich tool. But it wasn’t the shiniest.

Findings in the SpokenWeb archive

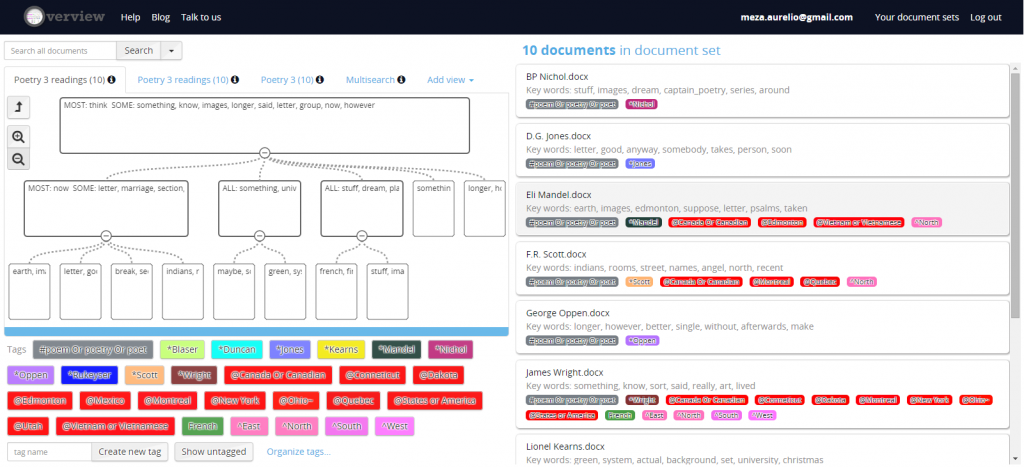

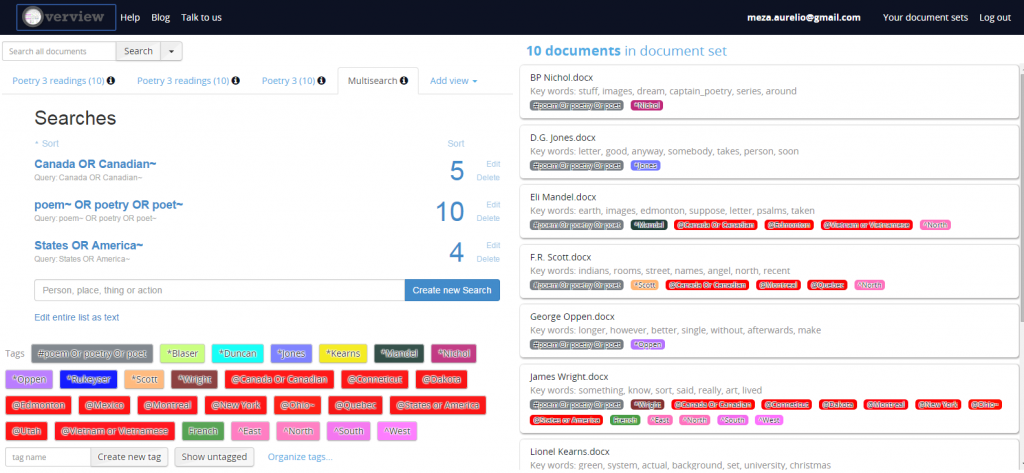

Fresh from Antonia and Corina’s workshop, we were excited to experiment with Overview, hoping to draw some quantitative results from the reading series transcripts. The possibility to tag, classify, and organize documents, as well as some of its visualisation tools, allowed us to access the documents in a different way, which went back and forth from a distant read to a close one. More than a visualisation program, Overview is an archive-classifying application; it helps to sort out big numbers of documents. In our case, it was not possible to aggregate all the readings made throughout the seven series, which would account for 65 poets. But we used the transcripts for the first three series and tagged the locations we found in them, in order to find if there were any recurrent mentions. Apart from topic classification, other functions of tagging include author/genre identification and reviewing control.

With our collections of extra poetic speech from the first three poetry transcripts of the SGWU Poetry Series, we began our tests with Overview with a specific question in mind: What can the extra-poetic speech, this “documentary residue,” tell us about the poets in this reading series, as well as their literary work? The “distant listening” approach we followed here to analyze the SpokenWeb archive suggests that these new forms of mediation have a strong influence on the way we consume, read, or listen to literary/cultural objects. Distant listening shifts meanings within the analytical process, and forces us to reconsider what is deemed important in a critical endeavor.

The fact that we were not able to analyse the poems read at every series (with few exceptions) guided our research to focus on extra-poetic speech. It is true that not all poets would explain in detail the content, form, or other aspects from their own work, but most of them would find it necessary to say a few words about it — and in some cases, such as Duncan’s, it would take a considerable amount of the reading time.

Although our approach was presumably distanced from the reading series as individual audio files, many initial assumptions were grounded in a close reading/listening approach. However, the fact that we could actually find patterns and correspondences among different readings helped us to identify whether these assumptions could be “quantitatively” confirmed. The use of tags on Overview to identify the mention of geographical data (places, locations, directions) provides significant information about how some poets perform their work in public, as well as it reveals some of the biases implicit in the reading series, which can probably be grasped by quickly skimming through the names of the invited poets, but which are confronted and confirmed through the tagging process.

One of these initial assumptions was that there was an evident slant toward North American/European authors, and therefore toward what Walter Mignolo, following Ella Shohat, would call their “enunciation loci”– the discursive “places” from which they talk about (2005). Nevertheless, can this assumption be proved through the methodological tools offered by Overview? Let’s have a look at the geographical mentions in the Poetry 3 readings, held throughout the 1968-1969 academic year.

Out of the ten poets who read in Poetry 3 (George Oppen, B.P. Nichol, Lionel Kearns, James Wright, Muriel Rukeyser, F.R. Scott, Eli Mandel, D.G. Jones, Robin Blaser, and Robert Duncan), most of them mentioned at least one city, country, or nationality. Although all of the poets were Canadian or American, only five of them mentioned “Canada” or “Canadian” (two Canadians — Mandel and Scott — and three Americans — Wright, Rukeyser, and Duncan). With the exception of Rukeyser, most of them also mentioned Canadian cities, such as Edmonton (Mandel), Montreal (Scott, Wright, and Duncan) or Quebec City (Scott, who was born there). It is significant to note that the three poets who mentioned “America”/“United States” are the same who mentioned “Canada”/“Canadian” (Wright, Rukeyser, and Duncan), so we might say that geographical location is more important for these poets than others in the series. Particularly in the case of Wright, he uses location in order to contextualize his work. Not only is he the one with more geographical references in Poetry 3 (he mentions Canada/Canadian, Connecticut, North and South Dakota, Montreal, New York, Ohio, and America/United States), but also the only one who uses the coordinates East/West to talk about different regions in the US.

What about non-English speaking locations? It is revealing to notice that only one poet (Scott) talks about Quebec, and not to refer to the province but rather to the city. In the light of the social events going on at that time, out of which the Quiet Revolution is the most remarkable, Scott’s solitary mention is actually revealing about the tensions and silences around social and political shifts in the region. Another major political event at that time was the Vietnam War, and only Duncan addresses it when he presents his poem “Soldiers.” In the case of Latin American countries, there is only one mention to Mexico (by Rukeyser, who like Samuel Beckett translated Octavio Paz into English) and one mention to Cuba and the Dominican Republic (Lionel Kearns).

These findings are provisional, as the whole SpokenWeb database has not been processed enough to reach to some general conclusions, but from preliminary analyses as the one above we can assume that most of the works performed in the Poetry 3 series were predominantly focused on North American places and (presumably) topics. Even the mentions to places outside North America, like Cuba or Vietnam, are connected to their relation with the United States.

Methods, Implications, Returns

Although we utilized overview as a tool that could enable ‘distant listening,’ our use of the software inevitably generated a typical close listening of the extra poetic speech that we derived from SpokenWeb. Our data sets from Poetry One, Two, and Three provided useful substance from which we could anticipate certain conclusions on topics such as poetic philosophy, performance tendencies, and topic content. Once we filtered our data through Overview’s algorithm, we began to question how this tool generated a novel set of information that we could not otherwise obtain from using keyword and word number searches in a standard word processor. Initially, it seemed to us that using software such as Overview would enhance our analysis of the material in a manner that would help us depart from a close read. However, we essentially returned to a typical literary approach to our extra poetic speech content through Overview. We had to reconsider our analytic stance towards this dataset, and to identify how exactly our examination would lead towards an effective distant listen of SpokenWeb. Ultimately, extra poetic speech does not qualify as literary text; first and foremost it is the speech sounds that precedes, interjects in, and concludes a given poetry reading. Extra poetic speech is inherently ephemeral – for unrecorded performances – given that it is spoken within the parameters of a reading environment and is not necessarily scripted in a physical document. However, with SpokenWeb, extra poetic speech is very much privileged as substantial and informative data in the form of audio recordings and transcripts. Naturally, a close reading of a transcript felt like the most organic analytic approach; yet, when we considered the forum — date, time, location — in which these poets delivered their readings and the significance of extra poetic speech, we began to reflect upon methods of cultural production and the tools that facilitated the Poetry Series’ preservation.

Phonotextual artifacts (collected in a database) provides invaluable material that enables us to consider things such as:

1) The physical bodies present during the reading

2) The physical space in which the reading occurred

3) Reading order among poets

4) Funding Methods

5) Performance styles

We have this dataset from the Poetry Series since individuals involved with its production recorded the readings on reel-to-reel analog tapes. Decades later, the formation of the SpokenWeb database created the necessary digital environment in which we can analyze and deconstruct MP3 sound recordings and written transcriptions that otherwise would have been lost given the readings’ ephemeral nature as spoken performances. This organized, catalogued, and coherent dataset produces a critical environment in which we can examine how these tools (reel-to-reel/MP3/database/transcripts) produce culture by re-creating the Poetry Series through contemporary technological constraints.

In this context, printed text does not hold its monopoly as the primary object in the fields of literary analysis and cultural production. Audio recording – and its component parts in the form of transcript and database – is one possible source from which we can mine digital data and derive meaning, creating new avenues to identify untraditional sources as the subject of literary analysis. However, we could not escape our methodological tendencies by applying a traditional close read. This phonotextual material perhaps necessitates a new methodology from which we can apply an appropriate analysis, or maybe it requires a blend of both close and distant (which we ended up performing). Regardless, the process remains opaque primarily because we were uncertain exactly what it meant to distant listen and read sound. We managed to derive some qualitative conclusions based on a set of quantitative data, but the most striking conclusion resulted from what we could perceive to be the relationship and evolution between forms of cultural production.

The SGWU Reading series recorded on reel-to-reel tapes represents a form of material cultural production. The reels themselves remained limited to a very small audience – perhaps even a non-existent audience prior to its rediscovery and digitization. Its conversion into MP3 entirely expands its material limitations given that it is widely disseminated across a broad audience with features that digitization and database cataloguing privilege. What began as a perfectly useless database (what Camlot described) now enables such endeavors as our specific experiment and the potential for others to perform countless other inquiries. As a form of cultural production, this multifaceted reading series (in its several manifestations) represents how our academic field broadens when expanded beyond print.

Works Cited

Camlot, Jason. “SGW Poetry Reading Series.” SpokenWeb. n.p. n.d. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

—. “Sound Archives.” Beyond the Text: Literary Archives in the 21st Century Conference. Yale University. Beinecke Library, New Haven, CT. April 2013. Panel discussion. MP3.

Duncan, Robert. “Reading at the University of British Columbia, August 5, 1963.” PennSound. n.p. n.d. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

Mignolo, Walter. “La razón post-colonial: herencias coloniales y teorías postcoloniales.” Adversus 2.4 (2005). Web. Nov. 2014.

Murray, Annie, and Jared Wiercinski. “Looking at Archival Sound: Enhancing the Listening Experience in a Spoken Word Archive.” First Monday 17.4 (2012): Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

“Overview Project Blog – Visualize Your Documents.” Overview. n.p. n.d. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

Sterne, Joanthan. “MP3 as Cultural Artifact.” New Media & Society 8.5 (2008): 825-42.

The post Reading series/reading sound: a phonotextual analysis of the SpokenWeb digital archive (Al Flamenco, Aurelio Meza, Lee Hannigan) appeared first on &.

]]>The post Dracula as Epistolary Database – Alanna, Jess and Hilary appeared first on &.

]]>For our Boot Camp, we worked together with programmers to create a database of the epistolary texts present in Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Alanna on her conception of the Dracula database project:

This project was a bit like diving into the deep end of a pool, never having seen water before. This is my first foray into the digital humanities, and it raised a lot of interesting questions over the course of the project. I considered whether using a digital tool for a Victorian project necessarily made it part-digital humanities. Does using digital tools make a person a digital humanist? Is a child using paints and brushes less a painter than Van Gogh?

Methodology

I decided to approach the project using a rough approximation of the scientific method. Just thinking about using a digital component changed my methodology—I was no longer only wearing my Victorian literature hat, I was heading into unknown territory and needed a helmet. For this reason, and also the sneaking suspicion that I had no idea how much I didn’t know, it seemed smart to document the journey as a sequence of hypotheses, predictions, experiments, and conclusions.

The Question

To build a digital tool for literary criticism is an excellent thing to do if it can contribute meaningfully to one’s research. In other words, does the tool have a function? It took some time to come up with the questions I wanted the tool to help me answer. I also reflected on why I wanted it – the digital humanities are a fashionable field, and it is easy to be drawn to them because there are lots of beautiful and interesting innovations, but ultimately, to build a database that does not serve a specific purpose is to build a toy, not a tool.

This project emerged from a question that came to me during the research for my MRP, Dracula’s Private Collection. What might happen when an epistolary novel, in this case Dracula, is restructured or reorganized in different ways? To find out, we built a database that would sort the items in the text by date, author, and genre, to see how the narrative might change. How might the text change in meaning if one were to read only the diary entries or letters? Does the text change in any significant way if it is reorganized to be chronological, or if we only read the men’s writing?

Beyond that, there is also a larger question concerning the archival nature of the novel. The novel is a collection of letters, diary entries, journals, newspaper clippings, and various other items that Mina Harker compiles into the archive and is ultimately the weapon they use to defeat Dracula. Dracula himself is something of an archive as well, because he is a masterful collector of languages, victims, and blood. Mina’s modern archive (modern because it is type-written by a woman) is used to slay this ancient, occult one, and so questions of archival violence begin to arise. Derrida’s concept from Archive Fever is useful here because authority is key.

Hypothesis: By creating a tool that can change the internal structure of Dracula, we will in turn create shifts in meaning that will yield new insights into the text.

Prediction: That this database will not only enable deeper study of the text, but also open up new ways of examining its structure and the metafictional constructs that make up the novel.

Experiment: Create a database, and use it to perform analyses of various sets of data.

Hilary and Jess on their experience working with the database:

In her probe for this week, Hilary wrote about the specific materiality of objects in the archive or “database” of a library, museum, or one’s personal collection—the material details that set them apart from one another. Just like any epistolary novel, Dracula’s objects of correspondence are catalogued within the pages of the book, made alike via their appearance on the page (the same font and spacing, etc.), but we, the reader, know that they are not alike in spirit. A letter from Mina or a telegram from Harker will feel like very different entities in our mind’s eye, as we read the story, because we extrapolate from what Stoker gives us into the signification of a letter, or a telegram, in all its ephemeral materiality. Yet the words of these documents also produce in us an affective response that sets them apart from one another. A telegram connotes urgency and is less intimate than a hand written letter, onto which we may imagine wax spilling and congealing or fingers smudging. Is consideration of such materialities (or lack thereof) considered distant or close reading?

To put this in conversation with the Manovich article, we can ask ourselves whether we are really de-materializing Dracula. Arguably, we are materializing it. To put it even more generally, we could question what our role is here, versus that of the programmers. (Especially given that the gender divide between us and them only served to further emphasize the gap in our knowledge). Here, for your (sadly?) comedic viewing pleasure, a photo that illustrates the chasm between us:

Are we interpreters of this data working with an entirely different paradigm-syntagm relationship? Haven’t we experienced a bit of an inability to communicate between disciplines because of this difference?

With these distinctions in mind, we approached the Dracula database project eagerly, hoping to learn something about code and, even better, to force ourselves to be interested in such an undertaking. While we did find the process fascinating, it was less because we became genius code masters, and more due to our interests in the mistranslations between us, as literature students, and the programmers. At one point, the three of us were talking about the “violence” that this type of project does to a work of literature like Dracula. The fact that these intimate epistolary exchanges between Stoker’s characters be reduced to a series of “stringlines” does seem violent, in a sense. Richard, the programmer, took issue with this word “violence” that was being used to describe his pragmatic pulling apart of the text, a reaction that interrogated our academic impulse to use such loaded words. The act of configuring a work of literature into a database in particular, is violent in that all the signified values conveyed by the language to the reader are eradicated and made useless. You can’t search for a document in the Dracula database by their affective or signified qualities (ie. “letters tinged with jealousy”)—it is only possible to identify entries by the simple imagistic qualities of the words that are present. A date, for example, has the date-word, the month-word and the year-word. There is nothing special about “October” other than the fact that it has an O followed by a C and etc. Lev Manovich addresses this when he writes that new media objects appear “as a collection of items on which the user can perform various operations: view, navigate, search. The user experience of such computerized collections is therefore quite distinct from reading a narrative or watching a film or navigating an architectural site” and that the result of the database is a “collection not a story” (2, 3). Manovich writes that “computer programming encapsulates the world according to its own logic” and he distinguishes between two types of “software objects” which this world is reduced to: “data structures and algorithms” (6).

One of the first things Richard the programmer showed us was the file of Dracula that he had found on Project Gutenberg:

Questions of provenance, text form and text edition came up in discussion of which version of Dracula was being fed/scanned into the database. Should we question the authority of a project like Gutenberg on such matters, we wondered. Does it matter that we’re working with a digital text rather than manually scanning/transcribing a physical copy? Is there a different materiality at play? Even with the physical book there is already a sense of duplication—the narrative is a sum of textual copies; Dracula is also a creature seeking replication, and as immortal and theoretically vanquishable as a digital copy. Jess mused that she found it fascinating to think of this database project as just another vehicle for Dracula’s world contamination and pathology in that it gives new meaning and agency to his monstrous textuality, which we are in effect enacting. In a weird way, in decomposing the text through the archival process, the text itself is becoming more real—an uncontrollable thing that both necessitates human activity to bring the database to life, and yet in its potentially endless unfurling/mutation becomes increasingly inhuman as the text-objects are dissociated from narrative patterns.

In order to “read” the markup language attached to file, the programmers needed to try different reader programs such as Eclipse, Java, then Python, and finally settling on C sharp.

They used an addition to C Sharp called Re-sharper which improves the function of the program. Richard told us he would have to delete the table of contents from the file’s markup language as it was superfluous to the database project (this is one place we talked about “violence”). Richard briefly explained object-oriented languages to us—first you create classes, such as “file reader,” and then objects, which must have the same name as a class. Once you’ve created your attributes for said objects, you can examine the strings of the file (or the sequence of characters, such as a sentence) and look for patterns which may be useful to you. Then you must create conditions, using words like “while” and “else” that will allow you to act upon the objects. Because we wanted the database to separate the entries by name, date and medium, we needed to create conditions that would act upon the stringlines within the file and pluck out all Journal Entries, for example.

The Future of this Database

HTML v. XMLTEI

The text is HTML, which is ultimately a code for presentation, for visual reference. The consequence of coding for display, rather than coding for meaning, is that this HTML version is really only useful to Alanna. It does not contribute to the larger scholarship, and it does not allow for other scholars who wish to manipulate Dracula digitally to do so except in very narrow ways. It might be fun for undergraduates who are working on Dracula but for larger projects, its usefulness is limited. The way to correct this is to create a version using XMLTEI because that is a language that codes for meaning. It looks almost exactly like HTML, and if you know HTML you can learn TEI quite quickly, but the reason it is so much more useful is because you can code for anything. If you want to create a personography, you can create TEI PersName tags around each occurrence of a given character’s name: “One day, <persname> Alanna <persname> walked down the street.” This allows for navigation through the text in a way that follows one storyline, because now that name has been linked semantically to an entry in a personography. Anything can be coded: names, dates, characters, objects, particular words, even smudges and marks on the paper of a given manuscript.

There will inevitably be more coded values and meaning than what any given scholar might use. The value of this is that the tags are never taken out, and that means that even if one person decides that dates are not important, someone else who does can do so with relative ease.

The way to use XMLTEI is to first check if the text you want to work on is an XML document that is also TEI compliant, or if it is just HTML. This information will usually appear in the header. It is also necessary to learn XSLT, which is a way of navigating TEI. Software developers will laugh because these are “so 1993,” as one recently put it. However, TEI has evolved into something of a specific digital humanities language, and so what is obsolete in the software world is not in the digital humanities. It is the most used language before making the jump to something like MySequel (a database language), and Python or one of the other high-performance languages.

To use these tools on Dracula and on other Victorian gothic epistolary novels will take a significant amount of time and also probably money, as well as training in TEI and XSLT. For these reasons, it is not practical to undertake them now for the sake of upgrading the Dracula database, but it does open up various possibilities for a larger, more sustained project in the future.

This brings us to yet another line of query: Is deconstructing Dracula in this fashion helping us experience the phenomenological horror that is Dracula on another level? Are we seeing the text assuming a new autonomy? Accessing Dracula through such a database in a way means breaking away from reading habits such that we are confronted with the impersonality of all texts. There is a disturbing interaction here between human and nonhuman elements that the database-building process reveals.

How much does the human recede into the nonhuman or vice versa?

Are we not seeing our own scholarly desires being translated into code?

Are we not probing into language’s otherness and translating it?

Some of the words that the programmers used interested us, such as “ugly” to connote variance (for example letters on which the dates deviated from the standard format, “day, month, year”). Whereas for Richard, “violence” was a hard word to swallow, Hilary noted that for her, “ugly” felt the same. Perhaps “deviant” would be a more accurate term? But that too implies that there should be some sort of standard formatting for dates of handwritten letters—an assumption that further erases the individual, human (or, in this case, character), handwriter from the letter-writing process (and the materiality that we continue to cloyingly hearken back to). The names of the programming languages also interested us. One of them, called “Lisp,” uses brackets for comments and apparently isn’t known for running smoothly. The name amused us as the implication of speech impediment made clearer the distinction between the human user of these languages and the coded language itself—as well as the awkwardness that may ensue when the two attempt to grapple with one another.

Jess wondered whether there wasn’t a kind of terrifying repetition to this whole process— or a sense of never really moving forward, and how this might offer a different experience of textuality? Dracula is itself a terribly repetitive narrative. We wondered whether, by participating in this project we’re looking for something external to the text— not part of the text itself but peripheral to it that the mechanics of archiving would render visible?

Graham Harman’s article, “The Well-Wrought Broken Hammer: Object-Oriented Literary Criticism,” in which he addresses the autonomy of textual objects from their relations and New Criticism’s holistic conception of the text’s interior, can speak directly to our project. Harman questions which features of a text or work of literature are essential to its definitive objecthood:

We can add alternate spellings or even misspellings to scattered words earlier in the text, without changing the feeling of the climax. We can change punctuation slightly, and even change the exact words of a certain number of lines before [the text] begins to take on different overtones…the critic might try to show how each text resists internal holism by attempting various modifications of these texts and seeing what happens. Instead of just writing about Moby-Dick, why not try shortening it to various degrees in order to discover the point at which it ceases to sound like Moby-Dick? Why not imagine it lengthened even further, or told by a third-person narrator rather than by Ishmael, or involving a cruise in the opposite direction around the globe?…In contrast to the endless recent exhortations to “Contextualize, contextualize, contextualize!” all the preceding suggestions involve ways of decontextualizing works, whether through examining how they absorb and resist their conditions of production, or by showing that they are to some extent autonomous even from their own properties. Moby-Dick differs from its own exact length and its own modifiable plot details…there is a certain je ne sais quoi or substance able to survive certain modifications and not others. (Harman 201)

Similar questions can be asked of our project—which uses such an object-oriented database model: are we stripping away at all the inessential qualities of Dracula? Are we left with anything that is essentially Dracula? That makes it recognizably such? Having said earlier that we are expanding the text of Dracula or metastructuralizing it it’s weird to think we are in the same gesture stripping it down to its bare parts.

By now, it has probably become clear that our boot camp project raised many questions for us, but these are, in fact, the types of questions that only a project such as this would fully force us to ask. In the face of the inevitable “So what?” we could respond that we have attempted to take Bogost’s suggestion to heart—that to build something can help you better understand it (or, in our case, help you realize how little you understand it)—that a project which represents “practice as theory” (111) is a worthy one, regardless of the outcome.

Works Cited

Brazeau, Bryan. Personal interview. October 3 2014.

Harman, Graham. “The Well-Wrought Broken Hammer: Object-Oriented Literary Criticism.” New Literary History 43.2 (2012). Print.

The post Dracula as Epistolary Database – Alanna, Jess and Hilary appeared first on &.

]]>The post Database Dance Floor: Manovich and Leckey appeared first on &.

]]>The idea of a database would be somewhat terrifying, I imagine, for the things that are databased (or archived), if they had the capacity to feel terrified. To be swallowed up by the endless object-pool of the internet is to be flattened out into sameness and obscurity. Gone are the hierarchical or affective qualities that we attribute to our scuffed record sleeves, spattered recipes, tear-stained diary entries and creased love letters — online archival tools such as email, YouTube and Itunes have successfully erased the traces that make objects significant (or even worthy of archiving), yet have also redefined the archive in terms of efficiency and ease of use. Lev Manovich recognizes this shift, writing, “New media does not radically break with the past; rather, it distributes weight differently between the categories that hold culture together, foregrounding what was in the background, and vice versa” (13). Not only does the new media database change the way we think about individual components of the archive, it also affects our conception of the narrative that often accompanies these types of catalogues.

Although it is now nearly fifteen years old (the same age, in fact, as Manovich’s article), Turner prize-winner Mark Leckey’s 1999 film Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore is an interesting art object (or collection of objects) from which to examine the re-distribution of narrative “weight” which Manovich addresses. Fiorucci is composed of a selection of found video footage of Manchester’s underground nightlife and dance scene, from the northern soul movement of the late 1960’s to the football casual scene of the eighties and the rave culture of the late-eighties/early-nineties. Leckey avoids overtly chronological ordering, linking these moments together, rather, with themes of nostalgia, youth culture, performance and anonymity. The film is intentionally jarring in its repetition of images and sounds, and although it may seem ambiguous in its narrative direction, it does have at least one clear trajectory: the movement from the individual dancer as subject to his/her subsumption into the throbbing crowd of the many-bodied dance floor. Passage of time is also emphasized, on the surface of the screen itself, by the near-constant presence of a rolling digital time code common to many early-nineties video cameras. The ascending numbers convey a sense of urgency as time is clearly ticking by, while the numbers’ incongruity between unrelated snippets of film supports Fredric Jameson’s definition of postmodern temporality as “a series of pure and unrelated presents in time” (73). Manovich offers a similar approach to new media objects, which he explains, “do not tell stories” and in fact have no “beginning or end” nor any “development, thematically, formally, or otherwise which would organize their elements into a sequence” (1). Leckey juxtaposes an awareness of the temporal progression with sudden freeze-frames of dancers’ faces. During these uncanny moments of frozen time, the “present” can be seen to “suddenly engulf” Leckey’s dancer-subjects with “undescribable vividness, a materiality of perception properly overwhelming” (Jameson 73). In this way, the viewer of Leckey’s video is also “engulfed” by the feeling of a constant present, and the “vividness” that Jameson describes can also, presumably, serve as an apt description for the rave experience itself.

Manovich notes that if the internet world “appears to us as an endless and unstructured collection of images, texts, and other data records, it is only appropriate that we will be moved to model it as a database — but it is also appropriate that we would want to develop poetics, aesthetics, and ethics of this database” (Manovich 2). He writes that database and narrative are “natural enemies” (8), but Fiorucci seems to straddle the space between the two. In a recent interview about his 1999 work, Leckey explains that he was driven by the nostalgia he felt for his youth to recreate “his own past using other peoples’ footage” and “reassemble his memories” using a “collage”-like, non-narrative method (Vimeo). It is this swapping out of our own memories for other peoples’ that is made possible by the features of the database which Manovich describes. How odd, that something as particular as a personal memory could be approximated through others‘ records of like memories. What becomes clear is that the memory, as an object itself, is less unique than we think, but that even in its interchangeability is still capable of producing the kind of affective response that we usually attribute to those creases, spatters and tear stains that materiality offers. Leckey confirms this, saying “It’s quite a sad movie…Fiorucci is an elegy for a time that’s gone” (Vimeo). He goes on to explain that although the film was made before YouTube, “it came about because of technology, because of computers,” thus tying his work to the capabilities of new media databases (Vimeo).

If the concept behind Leckey’s film is complimented by Manovich’s analysis of databases, so too can the “narrative” that Fiorucci takes on be seen to mirror the trajectory Manovich tracks, from old media to new — from hierarchical, special ordering to flattened, non-ordering — in its portrayal of the growing faceless dance floor. Throughout the film, the music to which the club-goers dance is nondescript yet rhythm-heavy; Leckey overlays his footage, culled from various temporal and spatial realms, with one relentless soundtrack of droning bass. The film’s use of relentless disco rhythms gives way to a “disembodied…eroticism” that divests the subjects’ dancing bodies of individualism (Dyer 104). Scott Hutson calls the specific type of movement inspired by electronic dance music “dance as flow” and he notes that this type of dance “merges the act with the awareness of the act, producing self-forgetfulness, a loss of self-consciousness, transcendence of individuality, and fusion with the world” (Hutson 39). In some ways, when dancing to electronic music, the self no longer operates the body. Instead, the movement of the body becomes involuntary, controlled by music and rhythm alone.

Beatrice Aaronson notes that, over time, the dance floor has indeed erased individuality, writing that “techno and rave dance floors have indeed become a ritualistic space of rhythmic cohesion that enhances togetherness and transgresses all constructs of difference…there is no hierarchy” (231). Reynolds points to an individuation of a different sort in Leckey’s film when he emphasizes that the “materiality” Leckey locates in his dancing subjects is, importantly, “insistent but mute” and not quite human in its “limb-dislocating contortions, foetus-pale flesh,” and “maniacal smiles” (Reynolds). This is exactly the kind of monstrous, “fragmented” subject Jameson predicted in “Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.”

If, according to Jameson, the postmodern subject is no longer “alienated” but “fragmented,” perhaps our urge to synthesize with the crowd is evidence of our residual alienation, and in fact, it is the actual act of blending that fragments us. Jameson writes that, in postmodernity, the “liberation…of the centered subject may also mean, not merely a liberation from anxiety, but a liberation from every other kind of feeling as well, since there is no longer a self present to do the feeling” (64). He almost skews this lack of self as positive—he writes that feelings are now “free-floating and impersonal, and tend to be dominated by a peculiar kind of euphoria” (64). Jameson portrays the relief from personal relationships and emotions as “euphoric,” similar to the feeling of the dance floor, where dancers are divested of individuality.

…But we have come a long way from my original linking of Leckey’s film and Manovich’s thoughts on database and narrative. Manovich writes that the “open nature of the Web as medium” contributes to its “anti-narrative logic” and that “If new elements are being added over time, the result is a collection, not a story” (Manovich 4). I’m interested in how a collection can also be a story — or rather how we always read narrative into collections, despite the disparity of its parts, even before the yawning terror of the endless database. Somehow, a video art collage like Fiorucci can host and inspire intense nostalgia for Leckey’s (and countless others’) personal memories without particularity. Does the fact that the Internet-archive is home to countless swappable objects mean that our pursuits of identity-formation are rendered inconsequential? Though Leckey’s film doesn’t follow Mieke Bal’s definition of a “narrative,” it does portray a “series of connected events caused or experienced by actors” (Manovich 11). It’s just that these actors do not remain constant. In fact, it is essential that they change. It seems to be Leckey’s vision that these people are interchangeable — and that their very presence on the dance floor, lost in movement, subsumed into the throbbing crowd, makes it so.

Works Cited

Aaronson, Beatrice. “Dancing our way out of Class through Funk, Techno or Rave.” Peace Review 11.2 (1999): 231-36. Project Muse. Web. 19 Nov. 2012.

Dyer, Richard. “In Defence of Disco.” 1979. New Formations 58 (2006): 101-108. Print.

Hutson, Scott R. “The Rave: Spiritual Healing in Modern Western Subcultures.” Anthropological Quarterly 7.1 (2000): 35-49.Academic Search Premier. Web. 22 Nov. 2012.

Jameson, Fredric. “Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.” New Left Review 146 (1984): 53-92.

Leckey, Mark, dir. Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore. 1999. YouTube. Web. 19 Nov. 2012. <http://2012popmusictheory.aburke.ca/2012/11/19/fiorucci-made-me-hardcore/>.

Reynolds, Simon. “They Burn so Bright Whilst You Can Only Wonder Why: Watching Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore.”Reynolds Retro. Ed. Simon Reynolds. 14 June 2012. Web. 22 Nov. 2012. <http://reynoldsretro.blogspot.ca/2012_06_01_archive.html>.

The post Database Dance Floor: Manovich and Leckey appeared first on &.

]]>