The post Search Engine Optimization: The Boot Camp appeared first on &.

]]>For a little over a year, I worked for an internet porn company.

It was very boring.

I’d been un- and under-employed for the better part of a year before, picking up contracts from private high schools and tour groups and science museums, but nothing that stuck. Then, a friend, another writer, told me I should apply for a job that was opening up where he worked. It was a writing job, full time, with flexible hours and sweet lord honest-to-goodness benefits. The job required a lot of creativity and was mostly self-directed. He’d be my immediate supervisor. I could start immediately.

The hitch — or, maybe not a hitch at all, depending on your perspective — was that the job would be for an internet porn company. This makes the job sound a lot weirder than it was, because generally speaking it was a terrible office job with co-workers who would microwave fish and an incompetent HR department, just like any other. But it’s ordinariness made the few things that were unusual all the more surreal.

I learned three things at this job that have proven actually useful: 1) how to definitively win an office rivalry (after months of feuding I hid the COO’s personal assistant’s Blackberry in a plastic Halloween pumpkin after she left it ringing at full volume on her desk all day one time too many, and it bears noting that her ringtone was Beyonce’s “Run The World [Girls]”); 2) how to churn out massive amounts of content in a short period of time (I had to write 10-12 blog posts every day, each in a different voice and with a different set of interests and preferences); and 3) what the hell SEO is.

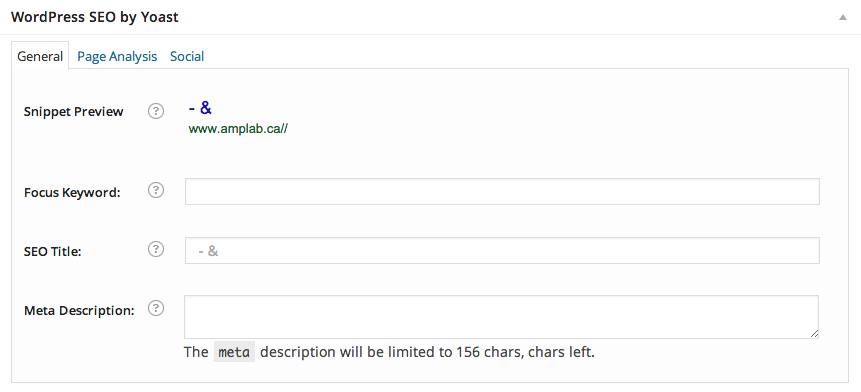

SEO stands for Search Engine Optimization, the process the defines how visible, and highly ranked, a website is according to search engine results, and by search engine, I mean Google. There are two kinds of traffic: paid, which directs traffic toward a site via ads (like AdWords), and organic, or “natural” traffic, the latter of which SEO strategies all attempt to generate. Rather than paying a search engine to bump your results to the top of the search queue (and labelled an ad in the process), SEO strategies seek to get a particular site as highly ranked as possible when specific search terms are entered.

Exactly how Google determines how sites are ranked depends on a number of factors, including site indexes (the internal structure that determines how content is arranged within a website), inbound and outbound links, and keywords and search terms. Content strategy is another key aspect of SEO, and involves not only how to structure the content of a website to ensure maximum impact on search engine results, but also when, how, and how frequently that content is deployed. Social media strategies, relationships with other websites, and dovetailing paid and unpaid strategies also factor in in various ways.

SEO is not something static; it’s not the type of strategy that, once you figure it out, can be implemented the same way forever. Instead, the way that Google determines how to rate and rank pages is constantly in flux. The process by which Google determines its search results is known as the Google Algorithm, which is constantly undergoing updates, changes and refreshes (each update has a fancy name now, such as “hummingbird” or “panda”). With each change, SEO strategies also have to adapt, sometimes subltly, other times dramatically.

For the purposes of this bootcamp, we’re going to focus on content, keywords and search terms. Our discussion and exercise are both going to focus on these elements, both because they’re most immediately relevant to most of the work we’re doing in this course, and a simple strategy involving both is something that anyone here could immediately take out and implement in their own writing and publishing lives to boost their search results. Also, these are elements of SEO that, while certainly not static in terms of their use and specific deployment, are some of the most stable aspects of any strategy. Search engines are always going to work via search terms; websites are always going to contain and require content. So however the Algorithm may change and strategies may shift, there is a certain stability in dealing with these elements first.

Why the hell does this matter?

So in the reading from this week, “Counting and Seeing the Social Action of Literary Form: Franco Moretti and the Sociology of Literature,” Tony Bennet discusses the ways that Moretti and his predecessors (including Adorno, Benjamin, Eagleton and Bakhtin) engage with literary form. He states that they are all, in one form or another, “all, in their different ways, preoccupied with questions of form, especially at the level of genre analysis as the aspect of literary form judged to lend itself best to the task of tracing the connections between, on the one hand, transformations or stabilities of form and, on the other, changes or continuities in the organization of economic, social and cultural relationships.”

SEO, and Google search engine algorithms, have had a profound impact upon the forms online content takes on. The way that content is composed, structured and deployed (at least from an SEO perspective) is determined not my the subject matter, but rather the needs of the content strategy. This effects everything from the length of a piece to the specificities of its internal structure. Optimized content has a form all its own.

Beyond that, the structures and scaffolding around SEO, keyword trees and the forms associated with WordPress plugins, are form in their own right. Concerned with brevity and specificity, they are both reductive and refining, diminutive forms and distillations of the content they define and describe. There is something profoundly useful about choosing an effective title, breaking a piece down into a few bare sentences for a description, and choosing a handful of relevant keywords. This is actually something we see done at the beginning of the Bennett piece: on the first page of the article, we’re given a title, an abstract, and keywords. The same tools that allow researchers to locate papers in scholastic databases are profoundly similar to what Google does with the web at large.

There’s creative potential here. There is something to subvert and exploit in the way that search terms and tags can be deployed. Their utility is not entirely descriptive, but rather can also be creative and expressive; this is perhaps most well realized in tumblr posts, many of which are almost entirely formed out of tags. We see a version of this with twitter hashtags as well, as a way to both gather and organize ideas and movements, but also to serve as a kind of aside, another means of expression, a layer of irony.

SEO also matters to everyone in this room because, as academics and producers of content, we all strive (at least we all should strive) to be read. The most cutting observation, scintillating analysis or brilliant exegesis means nothing if no one reads it. Putting your work out in the world, beyond the closed circuit of refereed journals and conferences (though these are definitely important too), is a critical first step, but readership is something that has to be built, not assumed. Keeping SEO in mind is one way to get eyes on your work, to make sure that what you’re writing or making or doing isn’t existing in a vacuum.

Finally, and maybe most crucially, it’s important to mobilize SEO strategies for writing that is actually, well, good. Writing in all its forms, from tossed-off blog posts to long-form journalism, becomes “content,” mere fuel for the online engine, something to be churned out and updated. As frequency, regularity, and adherence to form become ever more important to content strategies, the actual substance of what is being written becomes less and less important (as much as the utility of content and its appeal to visitors to a site is always a part of any strategy, this is not the same as good writing). So much of SEO and content strategy becomes about filling in the form with any old content, any scraped together pile of words so long as it is relevant enough and adheres to the requirements of keywords and form. There’s the opportunity for those who are producing quality content to take what they have and add elements of SEO to it, adapt what is already there to fit the form rather than create according to its dictates, serve good content rather than an impetus for creating weak content.

For a more in-depth tutorial on SEO strategy, check out this one designed for the Yoast plugin, which the AmpLab site uses.

Works Cited

Bennett, Tony. Counting and Seeing the Social Action of Literary Form: Franco Moretti and the Sociology of Literature.” Cultural Sociology 3 (July 2009): 277-297.

The post Search Engine Optimization: The Boot Camp appeared first on &.

]]>The post Reading series/reading sound: a phonotextual analysis of the SpokenWeb digital archive (Al Flamenco, Aurelio Meza, Lee Hannigan) appeared first on &.

]]>The Reading Series

In the past twenty or so years, a large number of poetry sound recordings have been collected and stored in online databases hosted by university institutions. The SpokenWeb digital archive is one such collection. Housed at Concordia University, SpokenWeb features over 89 sound recordings from a poetry reading series that took place at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia) between 1966 and 1974. In the early 2000s, the original reel-to-reel tapes were converted to mp3, and by 2010 the SpokenWeb project, using the SGWU Poetry Series as a case study, was well into its exploration for ways to engage with poetry’s sound recordings as an object of literary analysis.

The collection’s ‘invisibility’ prior to its digitization (for over twenty years the original reel-to-reel tapes remained undiscovered, unreachable, forgotten, or deemed unimportant) is a glaring reminder of printed text’s monopoly in literary analysis and cultural production. Certainly, the written manuscripts of some of North America’s most important twentieth-century poets would not have collected dust for so many years, as did this collection of aural manuscripts — a collection which, as Murray and Wiercinski observe, “[draws] attention to the importance of sounded poetry for increased, complementary or even new critical engagement with poems, and . . . [disrupts] the marginalization of poetry recordings as a subject for serious literary research” (2012). However, before the SpokenWeb recordings became available in an online environment — before they became objects — they were an aggregate of inert documentary data — that is, a collection of archived materials (recordings, posters, newspaper write-ups) that together formed a unit of cultural production (reading series), shaped by bodies (organizers, audiences, poets), spaces (locales), and institutions (scholarly, poetic). Indeed, in order for a reading series to become a coherent object of literary study, its traces, what Camlot and Wershler call “documentary residue” (6), must be properly considered, for they are the constituents of meaning-making through which hermeneutic analyses of recorded audio filter. In other words, the SpokenWeb collection “urge[d] us to consider [the sound archive] as a result of social and technical processes, rather than outside them somehow” (Sterne 826).

As a coherent (if partial) unit of study, SpokenWeb, or the recorded reading series in general, allows us to return (if artificially) to an ephemeral live event, see beyond the archived document, and interpret it as an aggregate, one that is historically, technologically, and culturally specific. But how do we approach this aggregate? What might this particular phonotextual anthology tell us about modes of literary production in Canada in the late 60s and early 70s? How do we begin unpacking this data set? What does it mean to distant listen, or how do we read sound?

We began with an assumption, drawn from a recording of Robert Duncan’s 1965 lecture at the University of British Columbia, in which he speaks for over two hours, lecturing about poetry and poetics and reserving very little time for the reading of poetry in general, which seemed to oppose his claim of being a derivative poet.

Duncan, whose derivative poetic philosophy can be understood as a reincarnation of Romantic concepts of self-disintegration, highlights the inherently paradoxical nature of so many mid-20th century poetry readings — that is, existential consolidation of the poetic self through expository articulations of self-effacement. Which is to say, Duncan renounces the lyric “I” but uses a significant portion of his readings to talk about himself, a trend that proved true in his 1969 Poetry Series reading. This we determined by using the timestamps on Duncan’s recording to create a ratio between poems and extra-poetic speech. By extra-poetic speech we mean the content in the space between poems, where Duncan actually lectures about his poetry, provides anecdotes, or comments on his performance. Excluding George Bowering’s introduction, Duncan reads for two hours, six minutes and fifty-six seconds (another long session, by standard). For one hour and twenty-two minutes, he reads poetry. The remaining fifty-two minutes are filled with extra-poetic speech.

The balancing of poetry and poetics in Duncan’s reading led us to consider how other poets in the reading series might have organized their performance, and what that organization might reveal. For Duncan, it illustrated how aural performance can complicate poetic praxis. How do other poets organize their readings? Are there patterns to suggest that particular schools of poetry favour a certain structure of performance? Do poets begin readings with shorter poems, to ‘warm up’ their audience, and read longer poems in the middle? Do men read differently than women? Is there a relationship between venue and performance? Date? Time? Audience? The SGWU Poetry Series spanned nine years — would there be any recognizable changes in these patterns over that period? It became evident that the aggregation of reading series data could potentially reveal the social, historical, and cultural contexts that shaped the reading series, and also the underlying ideological structures within which the series took place. However, this information is difficult to access because the tools through which we attempt to do so are opaque (temporally, medially) and biased (i.e.who gets recorded, when, where and why). The reading series’ transcripts, it turned out, were a rich tool. But it wasn’t the shiniest.

Findings in the SpokenWeb archive

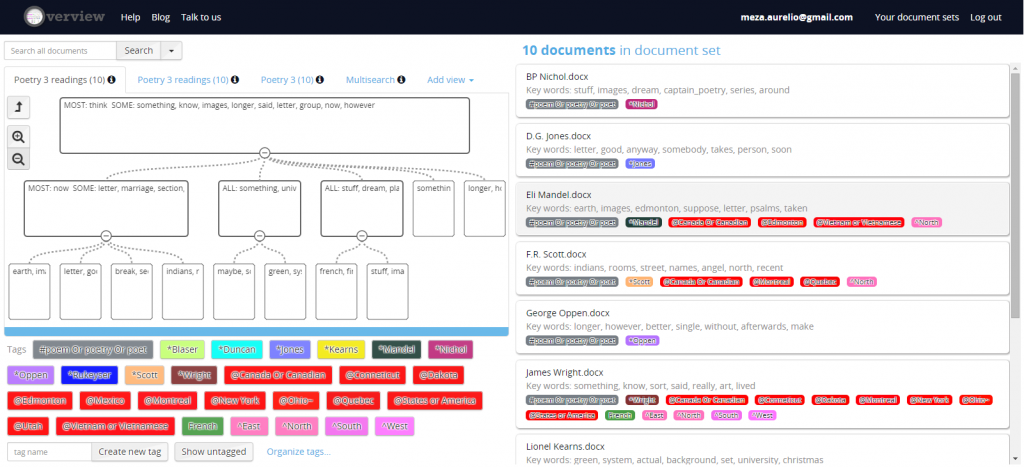

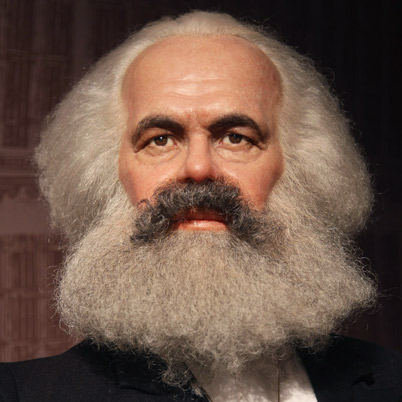

Fresh from Antonia and Corina’s workshop, we were excited to experiment with Overview, hoping to draw some quantitative results from the reading series transcripts. The possibility to tag, classify, and organize documents, as well as some of its visualisation tools, allowed us to access the documents in a different way, which went back and forth from a distant read to a close one. More than a visualisation program, Overview is an archive-classifying application; it helps to sort out big numbers of documents. In our case, it was not possible to aggregate all the readings made throughout the seven series, which would account for 65 poets. But we used the transcripts for the first three series and tagged the locations we found in them, in order to find if there were any recurrent mentions. Apart from topic classification, other functions of tagging include author/genre identification and reviewing control.

With our collections of extra poetic speech from the first three poetry transcripts of the SGWU Poetry Series, we began our tests with Overview with a specific question in mind: What can the extra-poetic speech, this “documentary residue,” tell us about the poets in this reading series, as well as their literary work? The “distant listening” approach we followed here to analyze the SpokenWeb archive suggests that these new forms of mediation have a strong influence on the way we consume, read, or listen to literary/cultural objects. Distant listening shifts meanings within the analytical process, and forces us to reconsider what is deemed important in a critical endeavor.

The fact that we were not able to analyse the poems read at every series (with few exceptions) guided our research to focus on extra-poetic speech. It is true that not all poets would explain in detail the content, form, or other aspects from their own work, but most of them would find it necessary to say a few words about it — and in some cases, such as Duncan’s, it would take a considerable amount of the reading time.

Although our approach was presumably distanced from the reading series as individual audio files, many initial assumptions were grounded in a close reading/listening approach. However, the fact that we could actually find patterns and correspondences among different readings helped us to identify whether these assumptions could be “quantitatively” confirmed. The use of tags on Overview to identify the mention of geographical data (places, locations, directions) provides significant information about how some poets perform their work in public, as well as it reveals some of the biases implicit in the reading series, which can probably be grasped by quickly skimming through the names of the invited poets, but which are confronted and confirmed through the tagging process.

One of these initial assumptions was that there was an evident slant toward North American/European authors, and therefore toward what Walter Mignolo, following Ella Shohat, would call their “enunciation loci”– the discursive “places” from which they talk about (2005). Nevertheless, can this assumption be proved through the methodological tools offered by Overview? Let’s have a look at the geographical mentions in the Poetry 3 readings, held throughout the 1968-1969 academic year.

Out of the ten poets who read in Poetry 3 (George Oppen, B.P. Nichol, Lionel Kearns, James Wright, Muriel Rukeyser, F.R. Scott, Eli Mandel, D.G. Jones, Robin Blaser, and Robert Duncan), most of them mentioned at least one city, country, or nationality. Although all of the poets were Canadian or American, only five of them mentioned “Canada” or “Canadian” (two Canadians — Mandel and Scott — and three Americans — Wright, Rukeyser, and Duncan). With the exception of Rukeyser, most of them also mentioned Canadian cities, such as Edmonton (Mandel), Montreal (Scott, Wright, and Duncan) or Quebec City (Scott, who was born there). It is significant to note that the three poets who mentioned “America”/“United States” are the same who mentioned “Canada”/“Canadian” (Wright, Rukeyser, and Duncan), so we might say that geographical location is more important for these poets than others in the series. Particularly in the case of Wright, he uses location in order to contextualize his work. Not only is he the one with more geographical references in Poetry 3 (he mentions Canada/Canadian, Connecticut, North and South Dakota, Montreal, New York, Ohio, and America/United States), but also the only one who uses the coordinates East/West to talk about different regions in the US.

What about non-English speaking locations? It is revealing to notice that only one poet (Scott) talks about Quebec, and not to refer to the province but rather to the city. In the light of the social events going on at that time, out of which the Quiet Revolution is the most remarkable, Scott’s solitary mention is actually revealing about the tensions and silences around social and political shifts in the region. Another major political event at that time was the Vietnam War, and only Duncan addresses it when he presents his poem “Soldiers.” In the case of Latin American countries, there is only one mention to Mexico (by Rukeyser, who like Samuel Beckett translated Octavio Paz into English) and one mention to Cuba and the Dominican Republic (Lionel Kearns).

These findings are provisional, as the whole SpokenWeb database has not been processed enough to reach to some general conclusions, but from preliminary analyses as the one above we can assume that most of the works performed in the Poetry 3 series were predominantly focused on North American places and (presumably) topics. Even the mentions to places outside North America, like Cuba or Vietnam, are connected to their relation with the United States.

Methods, Implications, Returns

Although we utilized overview as a tool that could enable ‘distant listening,’ our use of the software inevitably generated a typical close listening of the extra poetic speech that we derived from SpokenWeb. Our data sets from Poetry One, Two, and Three provided useful substance from which we could anticipate certain conclusions on topics such as poetic philosophy, performance tendencies, and topic content. Once we filtered our data through Overview’s algorithm, we began to question how this tool generated a novel set of information that we could not otherwise obtain from using keyword and word number searches in a standard word processor. Initially, it seemed to us that using software such as Overview would enhance our analysis of the material in a manner that would help us depart from a close read. However, we essentially returned to a typical literary approach to our extra poetic speech content through Overview. We had to reconsider our analytic stance towards this dataset, and to identify how exactly our examination would lead towards an effective distant listen of SpokenWeb. Ultimately, extra poetic speech does not qualify as literary text; first and foremost it is the speech sounds that precedes, interjects in, and concludes a given poetry reading. Extra poetic speech is inherently ephemeral – for unrecorded performances – given that it is spoken within the parameters of a reading environment and is not necessarily scripted in a physical document. However, with SpokenWeb, extra poetic speech is very much privileged as substantial and informative data in the form of audio recordings and transcripts. Naturally, a close reading of a transcript felt like the most organic analytic approach; yet, when we considered the forum — date, time, location — in which these poets delivered their readings and the significance of extra poetic speech, we began to reflect upon methods of cultural production and the tools that facilitated the Poetry Series’ preservation.

Phonotextual artifacts (collected in a database) provides invaluable material that enables us to consider things such as:

1) The physical bodies present during the reading

2) The physical space in which the reading occurred

3) Reading order among poets

4) Funding Methods

5) Performance styles

We have this dataset from the Poetry Series since individuals involved with its production recorded the readings on reel-to-reel analog tapes. Decades later, the formation of the SpokenWeb database created the necessary digital environment in which we can analyze and deconstruct MP3 sound recordings and written transcriptions that otherwise would have been lost given the readings’ ephemeral nature as spoken performances. This organized, catalogued, and coherent dataset produces a critical environment in which we can examine how these tools (reel-to-reel/MP3/database/transcripts) produce culture by re-creating the Poetry Series through contemporary technological constraints.

In this context, printed text does not hold its monopoly as the primary object in the fields of literary analysis and cultural production. Audio recording – and its component parts in the form of transcript and database – is one possible source from which we can mine digital data and derive meaning, creating new avenues to identify untraditional sources as the subject of literary analysis. However, we could not escape our methodological tendencies by applying a traditional close read. This phonotextual material perhaps necessitates a new methodology from which we can apply an appropriate analysis, or maybe it requires a blend of both close and distant (which we ended up performing). Regardless, the process remains opaque primarily because we were uncertain exactly what it meant to distant listen and read sound. We managed to derive some qualitative conclusions based on a set of quantitative data, but the most striking conclusion resulted from what we could perceive to be the relationship and evolution between forms of cultural production.

The SGWU Reading series recorded on reel-to-reel tapes represents a form of material cultural production. The reels themselves remained limited to a very small audience – perhaps even a non-existent audience prior to its rediscovery and digitization. Its conversion into MP3 entirely expands its material limitations given that it is widely disseminated across a broad audience with features that digitization and database cataloguing privilege. What began as a perfectly useless database (what Camlot described) now enables such endeavors as our specific experiment and the potential for others to perform countless other inquiries. As a form of cultural production, this multifaceted reading series (in its several manifestations) represents how our academic field broadens when expanded beyond print.

Works Cited

Camlot, Jason. “SGW Poetry Reading Series.” SpokenWeb. n.p. n.d. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

—. “Sound Archives.” Beyond the Text: Literary Archives in the 21st Century Conference. Yale University. Beinecke Library, New Haven, CT. April 2013. Panel discussion. MP3.

Duncan, Robert. “Reading at the University of British Columbia, August 5, 1963.” PennSound. n.p. n.d. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

Mignolo, Walter. “La razón post-colonial: herencias coloniales y teorías postcoloniales.” Adversus 2.4 (2005). Web. Nov. 2014.

Murray, Annie, and Jared Wiercinski. “Looking at Archival Sound: Enhancing the Listening Experience in a Spoken Word Archive.” First Monday 17.4 (2012): Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

“Overview Project Blog – Visualize Your Documents.” Overview. n.p. n.d. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

Sterne, Joanthan. “MP3 as Cultural Artifact.” New Media & Society 8.5 (2008): 825-42.

The post Reading series/reading sound: a phonotextual analysis of the SpokenWeb digital archive (Al Flamenco, Aurelio Meza, Lee Hannigan) appeared first on &.

]]>The post Boot Camp – Fucking Up with Brer Rabbit appeared first on &.

]]>To fuck something up – to deform – deformation. There is an immediate resistance to this prospect. Fuck up, deform, deformation – these words are instilled with a negative connotation – at least in so far as we are applying them to an object that we either admire or respect. Exploring the formal qualities or interpretative possibilities of a work of art is integral to the scholarly enterprise. The performance, the creation is the domain of the artist. Our lot is to sift through the final product (object) – observing, exploring and extracting possibilities of “meaning” through the application of absorbed methods of formal critical analysis (historical, psychological, etc.) and theoretical propositions that problematize and elucidate the functionality and relevancy of the chosen scholarly artistic systems. The goal is NOT to fuck it up (or to fuck up) but to contribute to the overarching influence or impact of the object/subject within the social, political and historical continuity of our developing culture. A conduit reaching across a social stratosphere, engaging a brotherhood/sisterhood of not necessarily like-minded fellow scholars, but scholars nonetheless who share a common language and theoretical foundation from which coherent analysis and regulated conclusions can be drawn, disputed, challenged and re-developed so as to allow for an intelligent discourse to grow and adapt to new critical propositions and methods in the pursuit of “understanding” and appreciation. Let the artists fuck it up and we’ll come in and put “Humpty” together again discovering new insights and culturally significant revelations (apocalypses?) along the way. Let Jackson Mac Low pilfer and “deform” Pound’s Cantos – we’ll expose the significance and debate the silence at the end. After all, we are the ones who have been in training for years – not to “create” but to explicate.

Or so I was led to believe.

But we fuck things up all the time – and we create. We develop the discourses that lead to propositional analyses that manifest into creative/created objects (articles/books) that become the subject of further critical and hermeneutic dissection. Hugh Kenner is as legitimate a target of scholarly research, as is James Joyce (think of The Pound Era). And we fuck up through our misreading and our ability to decontextualize and impose “meaning” through subjective politicalized agendas conforming to the critical flavor du jour. Scholarly research is a messy business and is sustained only via the whims of the “committee”. Cater to their focus, and the money flows. Piss them off (fuck up?) and you better have a trust fund if you want to stay in business. So we search for new avenues of excavation by which we can justify our status – and why not – what we do is a performance – a dance within the realm of the critical, a dance with clashing and transformative networks and discourses that cultivate a plethora of achievable potentiality. So let’s find innovative ways to fuck up, to perform and to create new archeological paradigms by which we can explore the evolving objects of our interest.

Man was first a hunter, and an artist: his early vestiges tell us that alone. But he must always have dreamed, and recognized and guessed and supposed, all the skills of the imagination. Language itself is a continuously imaginative act. Rational discourse outside our familiar territory of Greek logic sounds to our ears like the wildest imagination. The Dogon, a people of West Africa, will tell you that a white fox named Ogo frequently weaves himself a hat of string bean hulls, puts it on his impudent head, and dances in the okra to insult and infuriate God Almighty, and that there’s nothing we can do about it except abide him in faith and patience.

This is not folklore, or quaint custom, but as serious a matter to the Dogon as a filling station to us Americans. The imagination; that is, the way we shape and use the world, indeed the way we see the world, has geographical boundaries like islands, continents, and countries. These boundaries can be crossed. That Dogon fox and his impudent dance came to live with us, but in a different body, and to serve a different mode of the imagination. We call him Brer Rabbit. (Davenport, 3-4 Italics added)

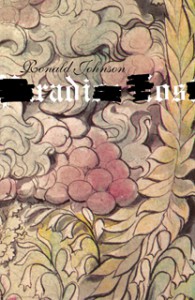

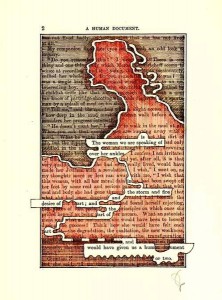

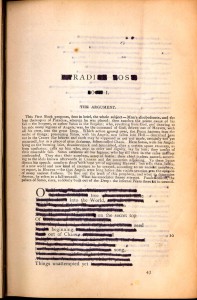

McGann and Samuels insist that their approach “does not stand opposed to interpretive procedures as such […] [it] moves to break beyond conceptual analysis into the kinds of knowledge involved in performative operations – a practice of everyday imaginative life ” (McGann&Samuels italics added). The “deformative critical operation” according to their paradigm encourages an exploration of “unvisited precincts of imaginative works” (McGann&Samuels 36). But, as Sample points out, once these unvisited spaces are revealed, the process resituates the original text within its hierarchical position and the orthodoxy of foundational critical inquiry is re-established “But however much deformance sounds like a progressive interpretative strategy, it actually reinscribes more conventional acts of interpretation” (Sample). This would appear to be a necessity if the critic maintains an institutional parameter whereby there is a precise object of focus (the poem). To not return to the original would be to engage in the “poetic” creative imagining of a new entity. The critic is no longer an expositor but is transformed into an artist engaging in the same creative gesture as Ronald Johnson or Jackson Mac Low (Radi Os and Words nd Ends from Ez, while necessarily creative critical commentaries on Paradise Lost and The Cantos respectively, are poems in their own right and are generally viewed as such within the academy).

from

Words nd Ends from Ez

by

Jackson Mac Low

________________________________________

Words nd Ends from Ez

I. From Cantos I-XXX

1/9/81 (EZRA POUND)

En nZe eaRing ory Arms,

Pallor pOn laUghtered laiN oureD Ent,

aZure teR,

un-

tAwny Pping cOme d oUt r wiNg-

joints,

preaD Et aZzle.

spRing-

water,

ool A P.”

cOnvict laUghter scaNy)

me, MaD E aZure TyRo,

of wAve-

cords,

If I rearrange the order of Eliot’s Waste Land (a form of reading backward) – begin with “Shantih, shantih, shantih” (The Peace which passeth understanding, the Peace which passeth understanding, the Peace which passeth understanding) and then “April is the cruellest month ….”, my deformative act has constructed a new object that can then be assessed as such (the immediacy of the foreign leading into the “normative” oxymoronic designation of spring as a negative condition suggesting that it is an alien assessment proposing an inversion affirming that April is, in fact, not cruel – or numerous other possible “interpretations”). Or if I replace the word Usura with “interest” in Pound’s Canto XLV – altering – will it now reveal, confirm or suggest an underlying potentially auspicious reading – upsetting the particulars regarding the (de)generative means and ways of production in relation to the distribution of wealth while removing the biblical nuances associated with usury? The point being that at this stage the poem, in its deformed state (and, of course the deforming rearranging could be much more involved) is susceptible to associative liminal approaches that could be isolated within the context of the new construct OR reconstituted into the original order of the text and assessed accordingly. Either way, does this deformation involve a “fucking up”? If this procedure constitutes a “[tearing] apart [of] existing structures and [using] the scraps” (Sample) then, perhaps, the original has been fucked up (though what we mean by “fucked up” is an interpretative issue) – though the results could still yield positive results within a broader cultural context. But, if the McGann/Samuels paradigm is maintained, then the original will be always present and the deformity is only a temporary measure by which new exploratory options have been revealed – a new imaginative act that opens windows into hidden spaces or “forms of discursive order which exceed conceptual formulation” (McGann and Samuels 37) – hardly a negative or “fucked up” endeavor. What can be said about academic archeology, however, is that the “boundaries” of imagination (in the geographical Davenportian sense) can more easily be crossed/ruptured and rearranged revealing that “Ogo” is very much at home and in sync with his trickster (deformative inducing) cousin Brer Rabbit – the innate, unavoidable application of the imagination in any scholarly practice shades all ensuing discourses – disrupting, deforming (fucking up?) and, ultimately revealing “possibilities of meaning” (McGann and Samuels 28) through performative gesturing.

Works cited:

Davenport, Guy. The Geography of the Imagination: Forty Essays by Guy Davenport. Boston: David R. Godine, Publisher, 1997. Print.

Eliot, T.S. The Complete Poems and Plays of T.S. Eliot. London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1969. Print.

Johnson, Ronald. Radi os. Chicago: Flood Editions, 2005. Print.

Mac Low, Jackson. Thing of beauty: New and Selected Works. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2009. Print.

Pound, Ezra. The Cantos of Ezra Pound. New York: New Directions Books, 1993. Print.

Sample, Mark. “Notes Towards A Deformed Humanities” SAMPLE REALITY. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.<http://www.samplereality.com/2012/05/02/notes-towards-a-deformed-humanities/> .

Samuels, Lisa, and Jerome McGann. “Deformance and Interpretation.” New Literary History 30.1 (1999): 25–56. Print.

The post Boot Camp – Fucking Up with Brer Rabbit appeared first on &.

]]>The post Bootcamp: Irish Music Club of Chicago appeared first on &.

]]>Francis O’Neill’s seminal collection Music of Ireland, and Irish Minstrels and Musicians, his principal book on the subject of his collection endeavours, both contain a photograph of Chicago’s Irish Music Club (Irish Traditional Music Archive; O’Neill, 479). The photo is dated as having been taken between 1901 and 1909, and shows 26 members of this club, with each member’s name in a caption below the photograph. Using this club as a case study, one might consider the applicability of network theory to interpersonal relations in circles of Irish traditional music in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Chicago.

The club itself was short-lived. It was formed around 1901; by 1912 “[Francis] O’Neill could say that not even a remnant of the Club remained and that few of the former members were on speaking terms” (Carolan, 39). While the club most likely broke down in the wake of personal disagreements between members, it is impossible to trace with any kind of accuracy the vicissitudes of individual musicians’ relations with each other. Were some friends, others rivals? Did any of these musicians teach tunes to some of the others? During the years of the club’s existence, each musician could have met with any other on a number of occasions, and interacted with him in myriad different ways. This leads to the conceptualization of something like Figure A in the document below.

Figure A depicts all 26 musicians as vertices, as well as all 299 edges connecting each musician with every other one. It ultimately represents a mere matrix of acquaintance. Each musician in the photograph would have at least been aware of the existence of every other one, and therefore could have interacted with him. This network diagram can then be viewed as a map of potentiality. We do not and cannot know – beyond the imperfect, patchy traces of written records – the details of who spoke to whom, nor for what length of time their acquaintance lasted. Nor could we accurately present this information in a network diagram, were it even available. These edges are thus not weighted and have no direction, to borrow Moretti’s phrase (Moretti, 3).

It is worth emphasizing that the network diagram in Figure A makes no reference to the broader network of musical transmission and interaction within which Chicago’s Irish Music Club existed. It is embedded in the broader global assemblage of practitioners of Irish traditional music, as well as that of historical Irish-American ethnicity. These overlapping and crisscrossing networks may be interpreted as a rhizome, whose points “can be connected to anything other, and must be” (Deleuze and Guattari, 7).

In Irish Minstrels and Musicians, Francis O’Neill recounts some interactions between the Irish Music Club and some external actors. To imagine these interactions as a network, the 26 vertices of Figure A may be conceptually lumped together in Figure B to create a vertex representing the club as a whole. Figure B then serves to illustrates a tiny slice of the club’s history. This second network diagram depicts the interactions of four individuals with the Irish Music Club at some point in its history. While Figure B does indicate some degree of contact, it does not reveal anything meaningful about the nature of the interaction. It does not show, for instance, that Rev. Richard Henebry and Rev. William Dollard visited Chicago in 1901 and mingled with some of the club’s members (O’Neill, 178), nor that John Coughlan, an Australian player of the uilleann pipes, arrogantly asked the Club to help him fund a journey to America (O’Neill, 253), nor that Australian fiddler Patrick O’Leary bemoaned in a letter that he could not partake in the music and companionship of Chicago’s Irish Music Club, as he was stuck in Australia (O’Neill, 383). The details remain textually tethered.

My last bootcamp, on O’Neill’s Music of Ireland, failed completely. This attempt seems more successful, but not by much. Figure A illustrates quite well the complex and ultimately unknowable potential interplay between some members of Chicago’s Irish Music Club. Wershler, Sinervo and Tien consider the intricacies of studying “cultural practices that you’re not supposed to know about” (A Network Archaeology of Unauthorized Comic Book Scans). While their focus is the digitization of comic books, their interrogation also seems to apply to the subject at hand. I would simply rephrase their question to: “How you do study cultural practices that you can’t know about?” One answer is to simply map out every possible edge, to highlight the network’s potential complexity.

Figure B, on the other hand, offers a clear depiction of Francis O’Neill’s accounts of the Irish Music Club’s interactions with external actors. This depiction is useful in that it positions the people involved in relation to each other in an intelligible way, but remains problematic due to issues of traceability. However this does not prevent, as I wrote in my last bootcamp, those fragments of available evidence from enacting instances of cultural convergence.

Works Cited

Carolan, Nicholas. A Harvest Saved: Francis O’Neill and Irish Music in Chicago. Cork: Ossian Publications, 1997. Print.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. “Introduction: Rhizome.” A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Massumi, Brian. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. 3-25. Print.

Irish Traditional Music Archive / Taisce Cheol Dúchais Éireann. “The Irish Music Club of Chicago, ca. 1901-1909 / unidentified photographer.” http://www.itma.ie/digitallibrary/image/irish-music-club-chicago

Moretti, Franco. “Network Theory, Plot Analysis.” Literary Lab Pamphlet 2. May 1, 2011. [Orig. pub. New Left Review 68, March-April 2011]. http://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet2.pdf

O’Neill, Francis. Irish Minstrels and Musicians, with numerous dissertations on related subjects. Chicago: The Regan Printing House, 1913. Print.

Sinervo, Kalervo, Shannon Tien, and Darren Wershler. “A Network Archaeology of Unauthorized Comic Book Scans.” Amodern 2: Network Archeaology (fall 2013). http://amodern.net/article/a-network-archaeology-of-unauthorized-comic-book-scans/

The post Bootcamp: Irish Music Club of Chicago appeared first on &.

]]>The post Boot Camp – Network Diagram Image – New Tools for Old Texts – Making it New? appeared first on &.

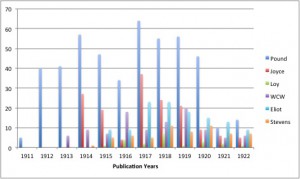

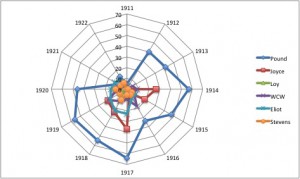

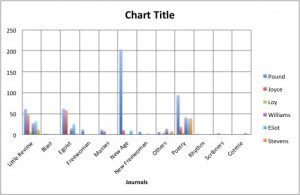

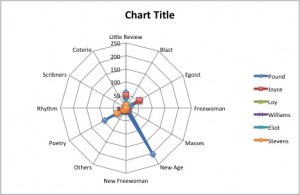

]]>The initial challenge encountered in approaching this boot camp involved the difficulty in deciding upon a subject. How could the quantitative methodology involved in producing a network diagram reveal a specific insight to an area of my interest and study? My initial conclusion was that should I be able to determine exactly how many times Joyce or Pound directly reference the Pauline Epistles in their writings, and where in their writings such reference were made, I would, indeed, have found a viable and vital method of inquiry. But, of course, this is what I am already attempting to do. My methodology, however, is the painstakingly slow process of close reading. I read and reread the texts involved discovering the relations and attempting to determine how those relations impact the development of the theological, philosophical, political and sociological dimensions of the primary texts involved and how that subsequently reflects the particular aspects of the Modernist agenda within the specificity of the reception and developed interpretations of Paul. But where would I begin to acquire the necessary data that could be utilized in the formation of a pictorial representation of such a project? I came to realize that I had to temper my ambition to suit my limited “digital” knowledge – I am not tech savvy and am very much situated in the idea of the text as the end all and be all object. So, I spent some hours surfing the net looking for sites that have focused on Paul and Joyce and Pound hoping to find some kind of data retrieval program that would assist me. What I concluded was that while there were sites that yielded much data, there was little that seemed to make the connections that I was seeking. I decided that my approach, again, needed to be modified. Relegating Paul to the back burner, I focused on Pound and Joyce looking for an approach that would relate to their early development (which is also the early development of the “high” modernist period I am interested in). With Moretti in mind I went looking for a subject that involved the “connections within large groups of objects” (Moretti 212) that corresponded to Joyce and Pound and that had been embraced by the digital world in such a way that I could retrieve enough data (without having to read through countless pages of text) to produce a diagram that would reveal some existing pattern relatable to the early development of their production. Thankfully, I came across The Modernists Journal Project (http://www.modjourn.org/): a searchable databank correlating early modernist journals with the writers and artists associated with them. Included in this databank were the more known journals such as the Little Review, Poetry and The Egoist as well as more obscure journals such as Rhythm, Coterie and Freewoman. Where would Joyce and Pound be situated in terms of the number of publications within these journals in relation to other known modernist writers of the period? Setting my parameters to cover the years between 1911-1922 and limiting my inquiry to twelve journals and four writers other that Pound and Joyce (Mina Loy, William Carlos Williams, T.S. Eliot and Wallace Stevens) I proceeded to explore the possibilities within the web site.

The results were of interest: Pound’s dominance regarding publication and influence was pronounced (as was to be expected). But the distribution of relevant publications by Pound and the other writers and how these published poems and essays were circulated among the different journals at different times suggests the need for further investigation and inquiry. Pound is the only one to publish in Freewoman – T.S. Eliot the only one in Coterie – and the journal Others is the most prominently represented journal of the lesser known outlets for the early modernists (with William Carlos Williams having more than double the number of writings there than Pound). What explains the higher activity of 1917? Why the disproportionate number of search “hits” for Pound in New Age? Looking at these graphs encourages these questions and many more that, while they may have already been explored to some degree, inform a relational pattern that is situated during a peak period of experimentation and the advent of an avant-garde that created it’s own distribution avenues in order to disseminate their particular views regarding the modernist moment (a comparison with the multiple avant-garde journals of Europe that were developed at the same time and any cross-over affiliations would be most interesting). There is clearly much more that can be done with this approach and with this web site tool – the circulation of the Poundian influence alone could be mapped through a more detailed and comprehensive accumulation of data. The numbers, once plotted into a diagram become less obscure and reveal patterns, clusters and networks that open areas of new possibility. Having now engaged in this procedure myself I can more clearly comprehend Moretti’s argument, though I align myself with James Murphy who takes a pragmatic view of Moretti’s work:

but I have continued to feel the rush of reading Moretti for the past decade and a half or so in part because he’s so persistently reminded us that we literary critics do indeed actually have data and we need to learn how to dig into it. Literary scholars are sometimes reluctant to acknowledge this fact because our métier is placing words like “data” and “facts” into question; we are awfully good at problematizing, but sometimes problematizing can be a problem in itself (Murphy, http://magmods.wordpress.com/2011/08/18/how-to-do-things-with-networks-a-response-to-franco-moretti/)

A couple of final notes: I am very disappointed with the graphs that I have posted. The 2-3 hours (at least) spent trying to gain a working knowledge of Excel produced sub-par results and speak directly to my limitations when it comes to utilizing the tools at my disposal (and I believe I am far from alone in this situation). Furthermore, I spent twice that amount of time attempting to transfer my data into the Gelphi program which finally defeated me when a recurring “java script” message suddenly and relentlessly kept intruding just as I had finally started giving shape to what would have been a much more informative diagram. The ensuing frustration has convinced me that my lack of computer and digital knowledge is unacceptable, and that in order for me to fully take advantage of the research tools at my disposal, I must rectify this weakness. This is not to say that close reading and hermeneutic approaches to research are any less important than they have always been. The digital tools (and theories) augment the established methodologies and together can yield much in terms of information and knowledge. The “computational analysis” of literature is with us and will undoubtedly become more and more relevant. The place of theory is still, at times, confronting resistance but the tools and the “networks” are helpful and necessary beyond measure. To Moretti, again:

what I took from network theory was its basic form of visualization: the idea that the temporal flow of a dramatic plot can be turned into a set of two-dimensional signs – vertices (or nodes) and edges – that can be grasped at a single glance. ‘We construct, and construct, and yet, intuition remains a good thing’, Klee once wrote, and that’s exactly how I proceed here, (mis-) using network theory to bring some order into literary evidence, but leaving my analysis free to follow any course that happened to suggest itself. (Moretti 211 italics in text).

Works Cites:

Moretti, Franco. Distant Reading. Verso: London, 2013. Print

Murphy, James. “How to do Things with Networks: A Response to Franco Moretti.” Magazine Modernisms, 18 August 2011. Web. 11 November 2013

The post Boot Camp – Network Diagram Image – New Tools for Old Texts – Making it New? appeared first on &.

]]>The post Bootcamp: Lorenzetti’s Allegory of Good and Bad Government appeared first on &.

]]>For this bootcamp, I wanted to see what Moretti’s network theory could bring to my own research, and more specifically to the interpretation of visual texts related to law and justice.

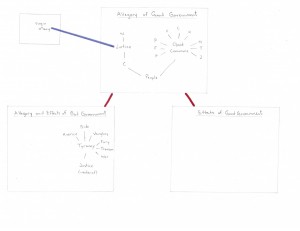

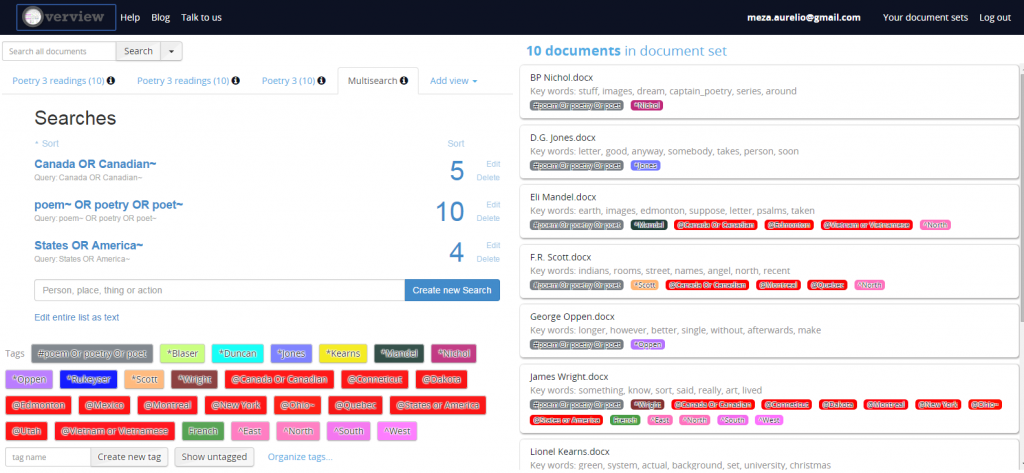

I chose to look at a group of three 14th century frescoes painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti: the Allegory of Good and Bad Government, located in the Town Hall of Siena. Since they are fairly complex paintings containing numerous characters, I thought that a diagram might be useful to shed light on the relations between the symbols. I first focused on the main central fresco. Since I still feel more comfortable with paper and pencil than with fancy software, I did it granny style.

In this diagram, the nodes are obviously the characters in the allegory, and the edges represent the connections between them. I simplified things a little bit, leaving aside for instance the soldiers and prisoners in the right lower corner.

In this diagram, the nodes are obviously the characters in the allegory, and the edges represent the connections between them. I simplified things a little bit, leaving aside for instance the soldiers and prisoners in the right lower corner.

The diagram makes evident some connections that the viewer of the fresco could easily miss if he or she didn’t pay close attention to the details. The cord that is handed down from the scales (held by Justice) to the People is, in fact, a fairly explicit edge. But there are a number of additional and more implicit connections between the characters that the diagram reveals. For instance, Justice is connected to Good Commune, but only indirectly: the link passes through the People. According to a common interpretation made by contemporary art historians, it runs from Justice, via harmony (Concordia) through the People, which are thus both guided and held in check, to Good Commune. But looking at the diagram, one could ask whether the direction of this edge could be reversed, running from Good Commune to Justice. In other words, the diagram incites us to ask more fundamental questions with respect to power relations.

Another set of relations revealed by the diagram is the one concerning the six virtues sitting around Good Commune. They are all connected to Good Commune, but not to each other, and also not to the main Justice figure to the left. The diagram also highlights the fact that Justice appears twice in the same fresco, and that the two representations are not directly related to each other. Does this duplication imply that justice was the dominant virtue at that time? Interestingly, the main Justice figure to the left is the only character related to Wisdom. This suggests that wisdom was, in the 14th century, considered essential to deliver justice but, since the node of Wisdom is not directly related to the node of Good Commune, not fundamental to the exercise of good government itself.

As Moretti suggests, we can also make experiments by playing with the diagram; variations may indeed be enriching. I didn’t re-draw the diagram in each case, since, thanks to Moretti’s own experiments, it’s quite obvious how this would look like in our case. What happens if we remove one of the virtues? Or if we get rid of the main Justice figure to the left? How would then good government be exercised? Remember that Wisdom disappears with the removal of this Justice. And what about if we eliminate the People? It is, after all, the very purpose of Justice and of Good Commune that would disappear. What would be the effect of getting rid of the central fresco? How do the allegory and effects of bad government (the fresco to the left) relate to the effects of good government (the fresco to the right)?

Notwithstanding these insights, there are important shortcomings to using network theory to analyze relations between numerous characters and symbols in an artwork. By way of example, the analysis of how the nodes are linked by the edges in Lorenzetti’s allegory has not revealed totally unexpected relations. This is probably linked to the fact that my analysis, similar to Moretti’s analysis of Hamlet, misses vast quantities of data; these frescoes clearly don’t contain large groups of objects necessitating quantitative analysis. Moreover, although not as explicit as a diagram, the frescoes are already visual representations.

We also have to be careful when trying to draw, from these frescoes, definite conclusions that are then converted into the diagram. Interpretation plays an important role. In the 18th century, for instance, the figure sitting on the throne to the left was thought to represent the city of Siena, and not Justice. And initially, the group of frescoes was called Peace and War; it’s only centuries later that the name changed, when good government itself became an important notion. In other words, there are alternative ways of reading these frescoes, something that the diagram does not reveal.

Furthermore, the diagram does not allow us to comprehend the overall symbolic importance attached to good government. There are two entire frescoes dedicated to good government (the allegory of Good Government and the Effects of Good Government), whereas bad government gets only one fresco combining the allegory and the effects. The frescoes are located in the room where the city councilors met; these frescoes were obviously meant to remind them of the consequences of their decisions and to influence them in a positive way (therefore the greater importance given to Good Government). But am I too concerned with close reading here?

Finally, I am wondering whether the conception of justice and of good government more generally is well represented in a diagram. It probably works in this European context, in other words in a context infused by Western thought. Following the discussion in Deleuze and Guattari, it could be speculated that in other cultures, justice might be better represented by other visual tools, as a tree or a rhizome, for example.

To try to gain more insights from applying network theory to my research, I thought I should expand my initial diagram. I therefore tried to represent the links between the three frescoes in another, even more simplified, diagram.

Hmmm. There are certainly many links to be made between the nodes in the different frescoes – an obvious one would be between the “strong” Justice figure in the central fresco and the “weak” Justice figure in the fresco to the left. But somehow I feel that it would be too arbitrary to try to make all these connections. Although there are definite connection between the frescoes, i.e. between the Allegory of Good Government and its Effects, only the fresco to the left contains further allegories and therefore more easily identifiable nodes.

Moreover, there are other paintings related to these three frescoes. There is, for instance, a painting of Virgin Mary in an adjoining room that is usually seen as being connected to the main Justice figure in the central fresco. The resulting interpretation is that the two women – Justice and Virgin Mary – are seen as reigning over the city of Siena. What about other paintings in the City Hall, and elsewhere in the city of Siena?

I would say that although its usefulness is very limited, the second diagram reminds us, once again, that making diagrams involves a lot of subjectivity and interpretation.

In sum, I believe that a few interesting connections and insights have emerged from drawing these diagrams of the Lorenzetti’s group of frescoes. But I am still not convinced of networks as an appropriate re-visualization style of representations, such as paintings and photographs. I certainly need to rethink how exactly Moretti’s network theory could be more helpful and meaningful in this context, and how an analysis of quantitative data could complement the more qualitative interpretation of visual representations.

Bibliography

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. “Introduction: Rhizome.” A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Massumi, Brian. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. 3–25.

Dessi, Rosa Maria. “L’invention du « bon gouvernement » – Pour une histoire des anachronisms dans les fresques d’Ambrogio Lorenzetti (XIVe-XXe siècle).” Bibliothèque de l’École des chartes 165 (2007) 453-505.

Moretti, Franco. “Network Theory, Plot Analysis.” Literary Lab Pamphlet 2. May 1, 2011. [Orig. pub. New Left Review 68, March-April 2011]. http://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet2.pdf.

The post Bootcamp: Lorenzetti’s Allegory of Good and Bad Government appeared first on &.

]]>The post Bootcamp: Trees appeared first on &.

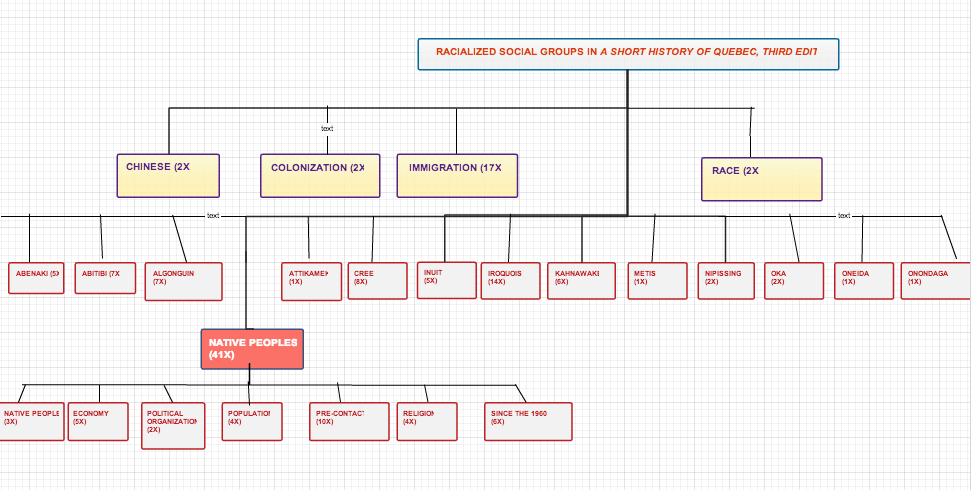

]]>I am a firm believer that the history of Québec is a collection of paradoxes and contradictions dressed in settler-colonialist and nationalist-driven social and political development. As a scholar deeply concerned with engaging in revisionist histories of Québec, I decided this week to take on a text that has plagued me for the past few years: A Short History of Quebec, Third Edition by John Dickinson and Brian Young. This text is often regarded as a cornerstone text in most studies and university courses on the province. I, however, take serious issue with the text.

Let’s face it, history is often written by those in power: white, heterosexual men. I have no problem with this, unless it results in the marginalization or erasure of other historical narratives. For this bootcamp, I have decided to re-construct the index of A Short History of Quebec in a tree diagram, with a particular focus on references to racialized social groups.

I must admit that I am absolutely inept at constructing diagrams. The only diagrams that seem to make sense to me are maps. While the visualization of the references to racialized social groups seem clear to me, I am sure this tree diagram may seem like a mess to someone else. If the tree diagram is supposed to present a concise diagrammatic representation of information, where did I go wrong (or right)?

Here is a breakdown of the information from the text:

| Chinese |

2 |

| Colonization |

2 |

| Immigration |

17 |

| race |

2 |

| Abenaki |

5 |

| Abitibi |

7 |

| Akwesasne |

2 |

| Algonguin |

7 |

| Attikamek |

1 |

| Cree |

8 |

| Erie (Native people) |

2 |

| First Nations (see Native people) | |

| Indian Act (1876) |

1 |

| Inuit |

5 |

| Iroquois |

14 |

| Kahnawake |

6 |

| Métis |

1 |

| Native People |

41 |

| Nipissing |

2 |

| Oka |

2 |

| Oneida |

1 |

| Onondaga |

1 |

Moretti reconfigures the tree diagram as a methodology for demonstrating “the interplay between history and form” (43). This is precisely why I decided that a tree may be an ideal medium to explore my contention with this particular history text. While the frequency of references are clear, as well as the sub-categorization of Native Peoples, I continue to feel that the tree does not articulate the lacuna of references to racialized peoples in a history text of Québec lauded to be the most comprehensive. We can see from the tree that there are a total of 106 references to Native/First Nations/Indigenous Peoples. There are no references to any other racial group other than Chinese (2 references). There is something amiss here…can the history of all other racialized groups fit neatly into the two references on race? While the numbers clearly explicate this situation, I continue feeling that the tree remains incomplete somehow.

Maybe the tree does not work alone..and must be juxtaposed with another three to references to other texts on racialized peoples in Québec—but the problem here is that these other texts generally do not factor into the discourse of Québécois history. I am concerned with the fact the A Short History of Quebec represents a very myopic presentation of racialized people in Québec.

In this bootcamp, I relied specifically on analyzing the index of A Short History of Quebec, and this source may present some insight into my dissatisfaction with my tree. The index of the text relies upon noting “important” keywords, however these keywords remain wrapped in a system of classification that may distort my understanding of the text. Moretti argues that a language tree “is a way of sketching how far a certain language has moved rom another one, or from their common point of origin” (46). In some ways, this tree is related to that language tree…but there is no indication of common points of origin, or history for that matter, only frequency. This issue of language and classification leads me to think about Deleuze’s image of the archivist. Who has given the archivist the power to organize the archive, to classify and name the documents? In relation to Foucault’s Archeology, Deleuze posits that “the words, phrases, and propositions examined by the text must be those which revolve round different focal points of power (and resistance) set in play by a particular problem” (Deleuze, “A New Archivist,” 17). I am not sure if the tree diagram I constructed summarizes the focal points of power (and resistance) I am attempting to address in A Short History of Quebec. Maybe the index has lead me astray, or maybe I simply need to take a workshop in graphs and diagrams…either way, I still think that it is clear that a “comprehensive” history text of over 400 pages should have more than two references to race.

Works Cited:

Deleuze, Gilles. “A New Archivist” Foucault, Trans. Hand, Séan. London: Althlone, 1988. 1-22.

Dickinson, John and Brian Young. A Short History of Quebec, 3rd Edition. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003.

Moretti, Franco. “Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for Literary History–3”. New Left Review 28 (July-Aug 2004): 43-63.

The post Bootcamp: Trees appeared first on &.

]]>The post Bootcamp: Our Humanities Theorists Tree-mapped appeared first on &.

]]>Bootcamp + Trees + Nov 7

“There is a constant branching-out, but the branches also grow together again, wholly or partially, all the time.” – Alfred Kroeber, Anthropology

Experiencing our class thus far, I must say it’s been less painful then expected to get my mind inside the theory circle. Once I became familiar with the ‘big names’ and most of the prevalent terms and ideas, everything became much easier. The circulatory nature of theory in the Humanities is evident as you read repeated names and quotes cited in each of our readings. And, as the semester has worn on, it has already become clear to me who speaks loudest to my sensitivities, my ways of working and my intuition. I have favorites: theorists I’ll keep tabs on and those I probably won’t. It’s the same for them. Some drool over Foucault while other go for Delueze and Guattari.

Franco Moretti had me at ‘graphs’.

This last series of Graphs, Maps, Trees is right up my alley because I am an intensely visual learner and communicator. Moretti gave us darn good reasons as to why this use of quantitative data and its visual representation add something to the textual humanities and can give us a new way of seeing. Of Graphs, Maps, Trees, I’m most interested in Trees. It probably has to do with my subject of study and its long lineage or my penchant for trees themselves. The graphs here feel less rigid, more organic and illustrate the more ‘messy’ bits of quantitative data better. Either way, I knew it was the perfect form for my latest question: the lineage of thought.

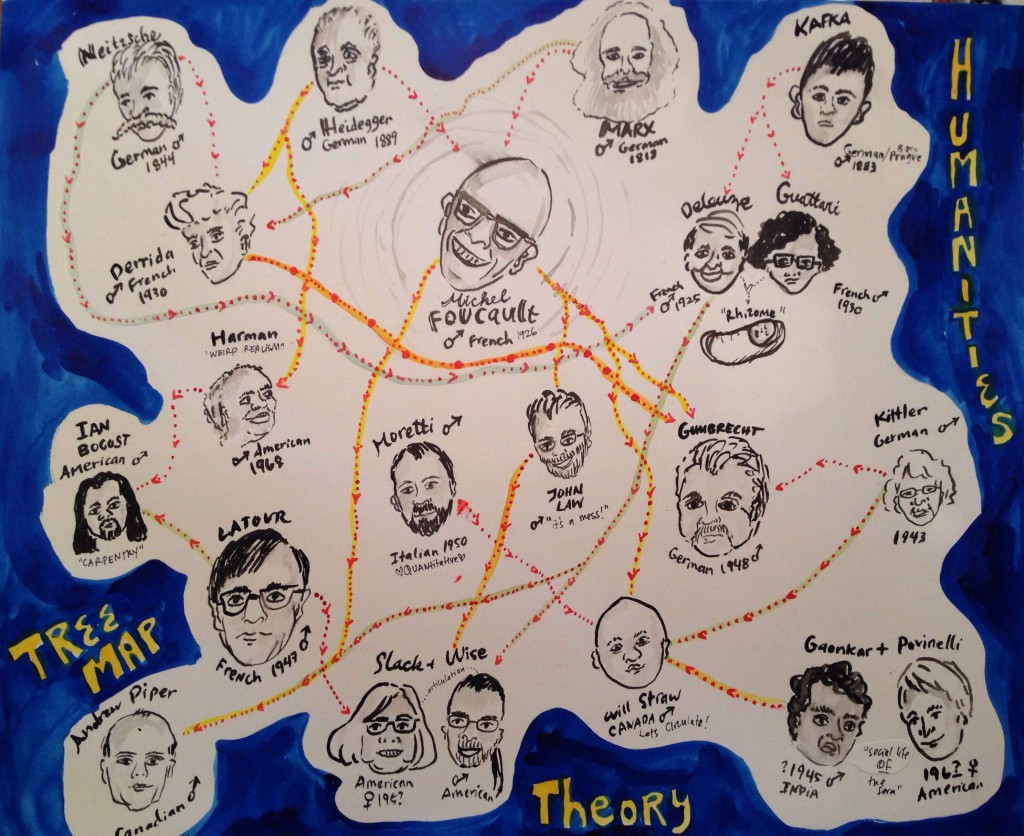

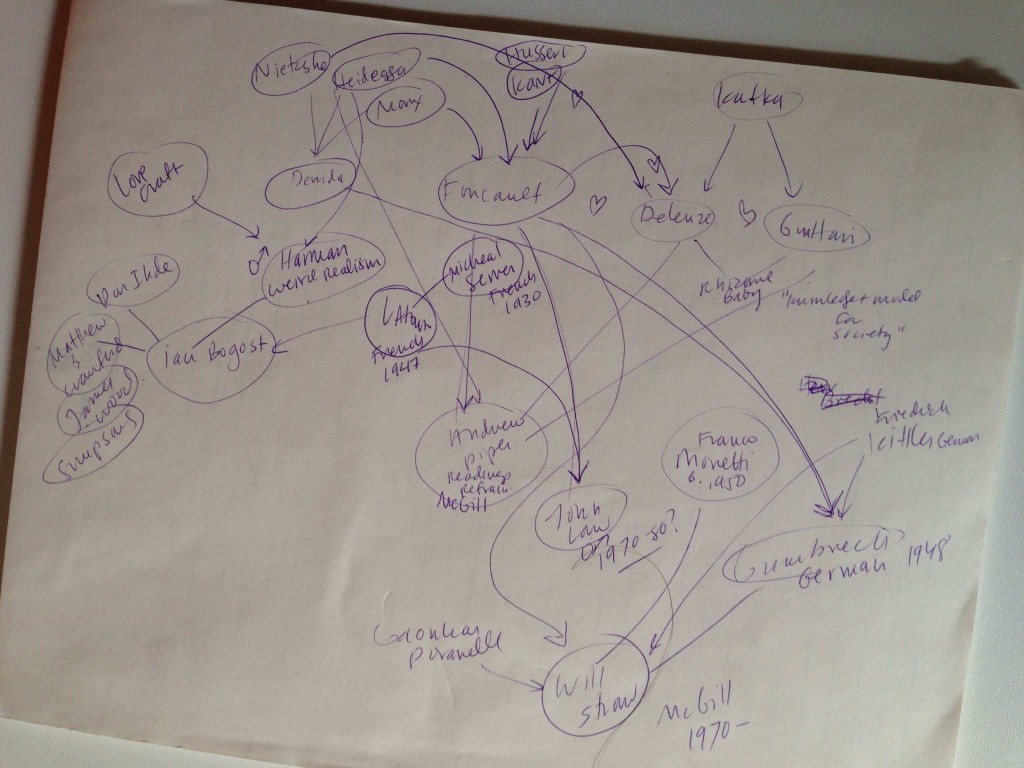

For this week’s Bootcamp, I’d like to experiment with our own syllabus. Who/what are we reading and what did those people read? How is the flow of theory/knowledge passed down to us and how do we become a part of it? Who inspired those who inspire me?

So, I made a tree graph.

I chose to do this with my own artistic interpretation because 1) I’m horrible with computer programs, 2) It’s dead fun to cartoonize the serious theorists we’ve been reading*, 3) We can see how the cartographer’s bias can influence our interpretation of the information. My method was similar to Moretti’s method of plotting Hamlet in next week’s Network article: I went through all of the readings and marked down each writer’s direct positive references within the articles we’ve read. If there was no obvious citation, I went online and did a search to see who their biggest influences were. I, by no means, exhausted these articulations. Sadly, I had to make many omissions and simplifications in order to fit it on the page. JP Harvey’s Deconstructing the Map and its warnings about the cartographer’s inherent bias is well taken.

My initial plotting of the theorist tree:

Although it looks like a network graph, it’s really a tree: I loosely placed them from oldest (top of the page) to youngest (bottom of page). And even though it’s messy – it actually does help me see things:

- If you want to be a theorist in the Humanities, you should probably grow a mustache.

- Foucault is by far the most referenced writer in our readings.

- There are other prominent authors that reference within the Humanities less but are referenced more (Moretti, Latour). Does this speak to writing style or more independent or interdisciplinary thought?

- If you do this long enough and are awesome at it, you will come to be referenced by last name only. Also, if you are in collaborative pair.

- Weirdly, there is little symbiotic sharing of intellectual love (other than the collaborative pairs). Most of this seems to simply be because of generational spans.

- At first glance, I thought: of course, it’s all a bunch of white guys from Germany and France. But if you look more closely at the ‘generations’ from top to bottom, you can see that even just in the last 50 years, the field has become much more diverse. I’m not sure if this speaks to the field at large or if Darren has just done a good job of making a point to include these scholars.

To place myself within the spaghetti dinner of thought, I’d probably plop myself down right below Moretti, John Law and Slack and Wise. I feel comfortable there in all directions: Mess, visual representations the present new information to the humanities and Articulations and Assemblages. Interestingly, these scholars are inspired by some of the others that I simply can’t get into – but now, seeing the lineage, feel closer to.

What do you see? Can you see anything at all? Does it help to clarify things or just confuse you? What does humor do to the information? Where are your pathways?

*Making Foucault look like the evil mastermind in the middle was a bit of an accident. Or was it?

And, just for fun, the winning mustache goes to: Nietzsche.

The winning overall hairstyle: Marx.

References:

Goodwin, Jonathan, and John Holbo. Reading Graphs, maps & trees: responses to Franco Moretti. Anderson, SC: Parlor Press, 2011. Print.

Harley, J. B., and Paul Laxton. The new nature of maps: essays in the history of cartography. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. Print.

Moretti, Franco. Graphs, maps, trees: abstract models for a literary history. London: Verso, 2005. Print.

The post Bootcamp: Our Humanities Theorists Tree-mapped appeared first on &.

]]>The post Bootcamp: The relative emptiness of maps appeared first on &.

]]>Maps themselves are also texts (Harley: 7-8). As raw material, I decided to take a map showing the projects and infrastructure planned to implement the (in)famous Plan Nord of the Charest government. The project, now called Le nord pour tous, hasn’t changed much under the new government, although its implementation has been somewhat slowed down due to the situation of the global economy.

My idea was to re-contextualize this map and to try to make sense of the territory through a native’s eye. How would a “traditional” native map of this territory, or part of it, have looked like? Perhaps like this?

A “traditional” native map challenges the European valuation of land and associated property claims. Space is organized very differently; it is more important to position people in, in relation to, and because of, the landscape (Anker: 112), than to reproduce exact and measurable graphic features.

The potential is there, but I realized that I would probably be speculating too much. I am, of course, a white woman (let’s forget my great-great Abenaki grand-ma – or what is my great-great-great grand-ma?) from the South, not knowing much about the North, not knowing enough about native Weltanschauung, nor about what a “map” might traditionally mean to a native person. Consider that before the arrival of the Europeans, Indian and Inuit languages did most likely not contain a word for “map”. So even the expression “native map” or “traditional map” has a colonialist touch. Moreover, I should probably not have drawn this “map” on a bleached and perfectly white sheet of paper (it’s recycled paper and may therefore be considered more “ecological”, but it’s most likely not “ecological” in any traditional native sense), but rather on a bark.

I ended up fearing that I would have to make a very long list of disclaimers, and that my “map” could be interpreted as a child’s drawing, or as making fun of or denigrating the lifestyle and intellectual capacities of native people.

I therefore changed my approach and tried to imagine how the first European explorers visualized the territory to be discovered. How did they map Quebec? How did they start? Perhaps like this?

Rather empty, right? That’s it, an empty space.

Since the first explorers didn’t know much about the territory (and did of course not think in terms of the political space that Quebec forms today), the “map” of Quebec should perhaps rather look like this:

Completely empty. Only a frame, an artificial frame, in which the map-drawer can inscribe whatever he or she (in that time, probably he) wants. The blank sheet, however, stands for the “potentiality, the yet unwritten laws and yet unrealized power” (Goodrich: 91). It becomes a representation of space but a space of representation (Siegert: 13).

Whether it’s the coastline, forests, mountains, rivers, native settlements, the movement of animals, mines – the map-drawer has the power to determine the scale, the focus, the relationship between the objects represented, in short to appropriate the terra nullius, the territory that is socially and legally constructed as belonging to “nobody”.

While every map, of course, starts with a blank sheet, or a bare skin, or a plain rock, the empty map in the context of a colonialist endeavor embodies the constructed emptiness of the space. In this sense, I believe that an empty, or nearly empty map of the North of Quebec is revealing of the ways in which the European settlers treated, and still treat, this territory.

Such a “map” does not reply to any questions or explain anything by itself, but it is a good way to ask different and more fundamental questions. As Moretti writes, a map “shows us that there is something that needs to be explained.” (Moretti: 84)

Work cited:

Anker, Kirsten. “The Truth in Painting: Cultural Artifacts as Proof of Native Title.” Law Text Culture 9 (2005) 91-124.

Goodrich, Peter. “The Iconography of Nothing” in Douzinas and Mead, eds, Law and the Image. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1999, 89-115.

Harley, J.B. “Deconstructing the Map.” Cartographica 26:2 (Summer 1989) 1-20.

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History – 2.″ New Left Review 26 (March/April 2004): 79–103.

Ryan, Simon. The Cartographic Eye – How Explorers Saw Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

The post Bootcamp: The relative emptiness of maps appeared first on &.

]]>

Order on Order (the story, the map, the disturbing landscape of…)

(bootcamp: the markdown)

.

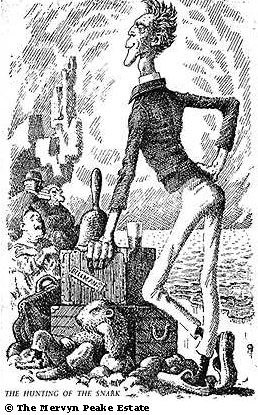

The map in Lewis Carol’s Hunting of the Snark is a blank. Yet they make it to the island (what is an island defined by a blank map?). Order in the Hunting of the Snark is a series of absurdities-as-rules brought about by the author, including the narrative itself which could be summarized as follows:

THE LANDING > THE VANISHING

Its sad this, but less sad than it would be without the humour of order, without lyric and narrative jest layered like the smooth membrane of a page (as a map of time) over nothingness and the inevitable (if a narrative ‘inevitable’ is not already a map of time). This “agony in eight fits” begins when the omniscient (or so the crew is lead to believe) Bellman lands his crew with care,

“Just the place for a Snark!” the Bellman cried, as he landed his crew with care; Supporting each man on the top of the tide by a finger entwined in his hair.

If we keep to the story, if we abide by the rules of this map, we will be safe, held gently above the abyss. We will be carried along with pleasure… to the end, far off in the future. It is a story for children.

My own copy of this epic quest (I think it was one of the first books I owned—it is definitely the book I have owned for the longest) is one illustrated by Mervyn Peake. I only discover today as I format this probe that the original (1884) illustrations were by Henry Holiday. We can compare the Bellman (Holiday -left; Peake-right):

Funny though, I thought the Bellman supported his people with a finger entwined in his own hair, not their hair! Needless to say I see the Holiday illustrations as latecomers, as wrong. The Peake illustrations were always ominous and disturbing for me. I owned this book before I could read. So the form of this book with its strange typography filled with quotation marks always fascinated me. Likewise, the two-handed mathematical calculations of the Butcher demonstrating how many times he said something while the Beaver looks on, deeply worried, were also a strange field of glyphs for me. This little book still resonates with this disturbing encounter with (incomprehensible) language and numbers. It is a feeling I still often feel when an external narrative of order or methodology presents itself.

On the cover of my copy of the hunting the title and author’s name is underlined in brown crayon (by me, I know). Inside the cover is the inscription ottwo.5 in the same brown crayon. Beside it, in my mother’s handwriting is my name and address. ottwo, if you can’t guess, is Ottawa. I do remember getting my mother to complete the inscription which marked my ownership of this little book. After I learned to read I was embarassed by the clumsy writing and mis-spelling. I’ve gotten over this.

Back to the map. I have spent most of my life without a tangible reference for the geography of the Hunting of the Snark. Fortunately, now I see images of the original 1884 illustrations which include Holiday’s very precise rendition of the map. It is a blank, a perfect blank, but one (to my dismay) framed by references to what lies haphazardly beyond this frame.

]]>