The post “It’s all about building trust”: An interview with Joanna Berzowska of XS Labs appeared first on &.

]]>Joanna Berzowska founded XS Labs in 2002 at Concordia, where they focus on “the development and design of electronic textiles, responsive clothing, wearable technologies, reactive materials, and squishy interfaces.” Previous to XS Labs, Berzowska studied and worked at the MIT Media Lab, and she co-founded International Fashion Machines with Maggie Orth. She holds a BA in Pure Mathematics and a BFA in Design Arts.

The kind of work that Berzowska engages in is profoundly interdisciplinary and crosses distinctions that we might automatically put up between design, industry, art, and theory. Her work has been shown at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York, the V&A in London, and at Ars Electronica in Linz, Austria, among others. Her lab at Concordia is located on the 10th floor of the EV and is part of the textiles cluster.

I met Joanna Berzowska for a coffee in St. Henri on December 10 to discuss wearable technology, her experience working at the MIT Media Lab, the agency of things, and what she believes is important for building an interdisciplinary space.

First of all, why do you call XS Labs a “lab”? Instead of say a “studio”? With International Fashion Machines, for example, I notice they call themselves a “company” — why “lab”?

I think part of the reason I originally called it a lab was just out of habit, because I was at the MIT Lab, and “lab” implies a kind of research culture… I’m thinking about it right now, because I guess I’ve never thought about it in depth… So part two of my answer is that it was a very direct, easy way of referencing research culture. Part three is a very strong emphasis at the time — when I was hired by Concordia fourteen years ago — to re-brand the institution as a research institution as opposed to a teaching institution. So when I was hired, I was basically told, your teaching doesn’t matter, your service doesn’t matter, all that matters is your research and how much money you raise. I think it was a turning point for the university, it was like the institution swung one way, because very strongly it was trying to position itself as a viable research institution at the time. Since then, the pendulum has really swung the other way. Now I think with the new president, Alan Shepard, he’s trying to find a comfortable middle that supports research as well as entrepreneurship, but at the same time recognizes that Concordia will never be a pure research institution and that’s what Alan always says — we can’t compete with McGill, we can’t compete with Ivy League–type schools, Concordia is unique. But when I was hired, the push was really, for a year or two, it’s all about research. So that’s part three of my answer, which is political in a sense. Going back to part two, it was important that “lab” reference research culture in a direct way, especially being in the Fine Arts, where, at that time, all the funding bodies and all of the potential sources of research income did not recognize what we now call “research-creation” as a viable way of working.

What’s interesting is I originally called it “XS Labs,” and even within that there’s an embedded critique. “XS” official stands for “Extra Soft” and it’s about soft circuits, it’s about soft electronics, but of course when you read it, it also sounds like “excess,” so there’s an embedded critique of a kind of contrast between a lot of research in Humanities, which is inherently critical of how we apply technology or how society embraces new changes, and then research in let’s say the sciences or Engineering, which don’t question it as much, but really just pursues innovation. The reason I chose the word “XS” was to have this critique. A lot of what I’m doing is in Engineering, science-type research, and we’re just going to put as much electronics as we can into all of these textiles and wearables, but, being in the Fine Arts, I’m also aware that we have to do so in a very deliberative, interrogative way, and question it at each step of the way. So that’s very much the tradition of XS Labs. And also, since XS Labs started, it’s XS Labs, colon, and what comes after the colon has evolved. So now I do refer to it as a design research studio. I’ve examined every couple of years the kind of work that we do, and these days I call it a design research studio, but the name is still XS Labs, so I guess I just want it all [laughs].

You’ve worked with the MIT Media Lab’s Tangible Media Group. This semester we’ve read a bit of Stewart Brand and have talked about California ideology and its very utopian take on technology. I read in an interview with you [with Jake Moore] where you were talking about researchers such as [Steve] Mann or [Hiroshi] Ishii who work with wearable technology in a way where it’s an exoskeleton or a kind of protective layer. And I was wondering if “Extra Soft” is a response to this kind of ethos that came out of working with the Media Lab and this situation where technology is celebrated as utopic and where wearable technology is something protective.

Yeah. So at the Media Lab there was definitely a strong gender divide actually, between how wearables were tackled by male researchers — and also, maybe coincidentally, the female researchers had more of a background in design or the arts. These are all stereotypes, which unfortunately were instantiated in my experience. So, women who I worked with, like Elise Co, Maggie Orth, who was my business partner for a while, Amanda Parkers, who came later, who’s now very active in the space, and then the dudes that I worked with, who were Brad Rhodes, Thad Starner, who ended up working for Google Glass, and Steve Mann, who’s a prof now at U of T [University of Toronto] — the women had more of a design and art background. I’m not saying it’s necessarily because of gender that they were more in touch with embodied sorts of questions, perhaps it was because of their past training, but maybe the past training was tied to gender. There was in fact one woman who was a really hardcore engineer, she still is, and she worked with Ros Picard [Rosalind W. Picard], who’s also a woman and also a hardcore engineer, so maybe the background training is more relevant in terms of the women that I worked with who were more interested in what we now refer to as embodied interaction, and considering the body as crucial — they were interested in textiles and the surface of the skin and what I now call beyond-the-wrist interaction —

Beyond the wrist…?

Whereas the dudes were really interested in things that you can manipulate with your hands and head-mounted displays, I was more interested in what happens on the rest of the body. And in many ways what happens on the rest of the body can be considered as dirty or sexual or smelly or provocative, so that doesn’t fit as easily into an Engineering research model, where you don’t have a specific problem to solve. And of course there are many problems, like how do you track baby kicks during a pregnancy, or whatever [laughs]. But, I certainly was more interested in the textiles, the rest of the body, how can we embed computation in textiles rather than attach devices to our bodies. And one corollary of that is also an interest in simpler kinds of computation. So, you know, the more cyborg approach to wearable computing basically strives to develop a computer as powerful as possible that is wearable and portable and now we have them [points to phone recording conversation] — these phones are kind of that, right? So, keep in mind this was twenty years ago, and the idea was, how can we take our computer with us all over the place? And now we do it with our phones, it’s funny. But back then, it was basically, you had to put the hard drive in the backpack, you have to take it all in pieces, have a huge antenna for your satellite GPS, etc. That’s wearable computing very literally, where you wear the same kind of computer that you have on your desk, whereas with my electronic textiles and the soft computation, it wasn’t a computer as you know it from your desk, but computation, how can you have wearable computing that is about simple kinds of interactions or simple kinds of functionality that are more interested perhaps in well-being or pleasure or just everyday experience or communication rather than just taking your computer from your office. That’s where the Extra Soft comes from, and there’s so many references, because also there’s hard science versus soft science.

It also sometimes seems like a lot of wearable technology aims to be “corrective” somehow, but you’re not really trying to “correct” the body. You’re trying to do something different.

“Extend” is usually what I say, whatever that means. Or not bring about some huge productivity gain or something but instead allow us to experience the world in a slightly different way.

To go back to the lab for a minute, is XS Labs one lab space or is it a series of lab spaces now in the EV?

Going back to the lab I realized there was something else that I wanted to say, so I’m glad you brought it up again. Another reason why I called it a “lab” is also that I wanted another way of working with my students. Traditionally in the Fine Arts when you work with grad students, they work on their own individual projects and you maybe advise them, you provide critique, whereas in the sciences and Engineering, they’re research assistants and you pay them for their time and they work not on your project but on a group project. I remember when I first came I was always using the plural “we” even though I only had maybe one research assistant, and people were very surprised, they were like, why aren’t you saying “I” or “my work,” and it’s because I was coming from a research lab culture, where every research paper that’s published has multiple authors, and you don’t work alone, ever, so that was another reason why I wanted to call it a “lab” and to train the students that I hired to not think of it as a job but to think of it as a collective inquiry that everybody will be credited for and everybody will benefit from. There were a lot of issues that we came up against of course where there was confusion between what would be their own individual practice and what is the research lab practice, so I tried to have very specific guidelines around how we credit, what people can take credit for, and how everybody had to credit everybody else’s work, and that’s a whole other kind of discussion.

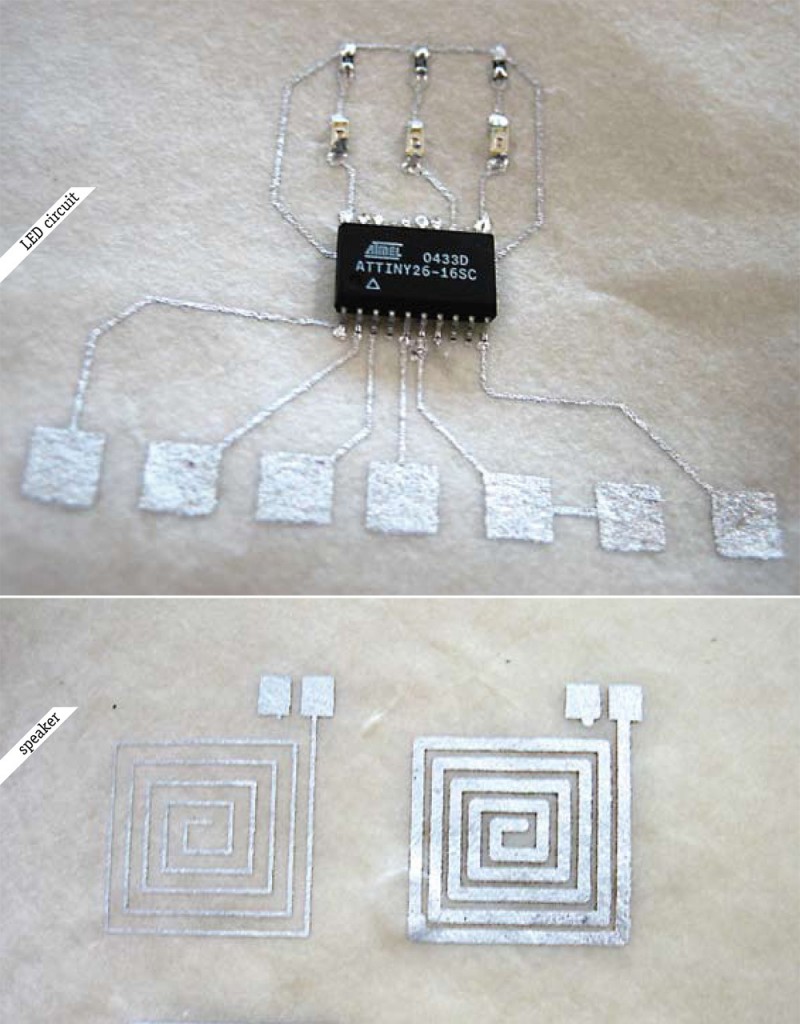

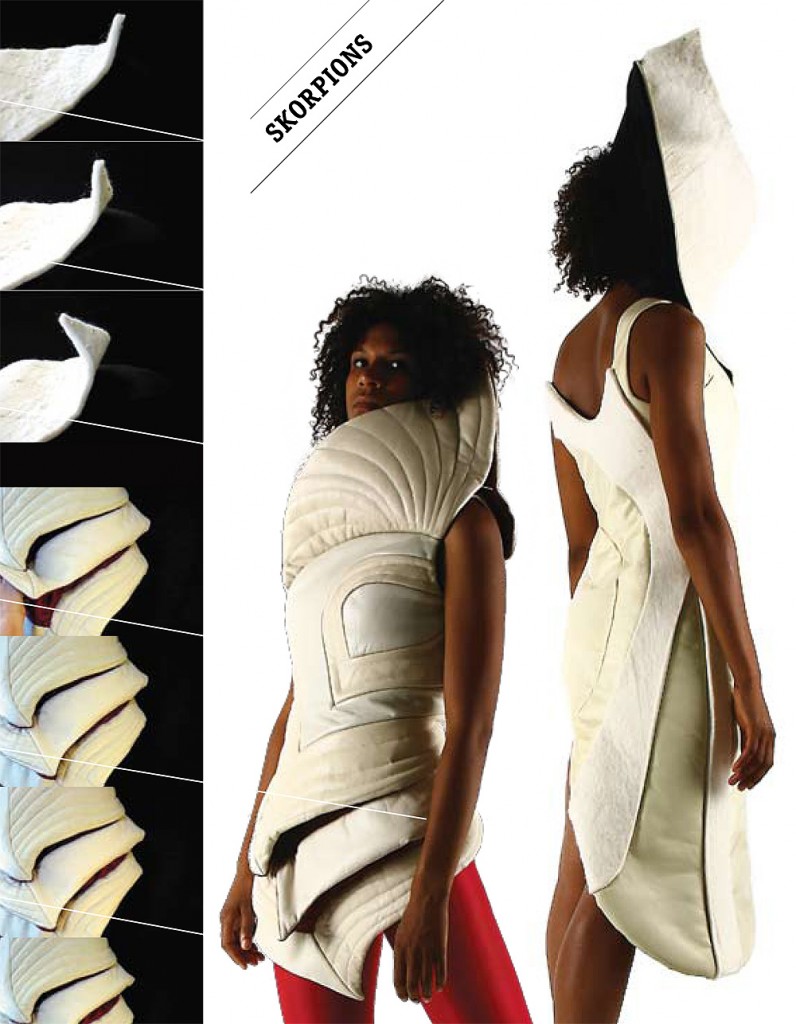

In terms of physical space, we’ve always had one space that’s shifted over the last fifteen years, that’s smaller or larger, that was like our headquarters. Then through Hexagram and other facilities we needed to use or have access to other spaces either through the more technical work we needed to do, like the weaving, or, at one point, I was collaborating with a prof in Materials Science on Nitinol, so we had all of these other spaces where work was done, mostly leveraging specific facilities and expertise. With Materials Science we needed specific furnaces to shape the Nitinol and quench it. We’ve got different kinds of looms or laser cutters. Or, collaborating with École Polytechnique, we’ve had some of our students there developing new fibres. But we’ve always had this little central headquarters. [Nitinol, “also known as muscle wire, is a shape memory alloy (SMA) of nickel and titanium that has the ability to indefinitely remember its geometry”; it is used, for example, in XS Lab’s Skorpions dress.]

When you yourself go into the lab, do you have any daily rituals that you find yourself performing there?

I’ll just say that I was Chair of the department for three years and now I’m on sabbatical and I’m pregnant, so what I do now does not reflect historically. Maybe I’ll just talk about the previous ten years, when there was a strong routine and a strong practice. I always had my days organized — certain days I devoted to teaching and office hours — certain days to service — meaning all the committee work, etc., and all of the research assistants who worked with me, some of them were grad students, some of them were undergrads, some of them were affiliates, there was really a wide range of different ways that I worked with students and research assistants. We had one weekly meeting, where everybody was expected to attend. So that was a sort of ritual where we’d touch base and I would give goals and guidance to everybody for the week. I also had somewhat of a hierarchical structure, where students who had been there longer would be responsible for training some of the younger students, and by younger I don’t mean age, but the newer ones. A lot of the culture in a research lab isn’t about hiring skilled personnel, it’s about training HQP [Highly Qualified Personnel], that’s what we write in the grant proposals [laughs]. So I hire students with potential who don’t necessarily have the skills that I want them to have, and part of what we do is train them. I would pay them to take workshops or classes, but I would also really expect them to teach one another and I would hire very complementary kinds of personalities who could teach each other, and the work is intrinsically interdisciplinary, which is where I think you’re going with this anyway. So that kind of collaboration was really crucial to the success of the work.

I’m very interested in research-creation. Would you say there’s any divide in your work between the research and the creation? Do you have a space more for inspiration and a separate theoretical component, or is that tied together for you?

It’s really tied together because the creation is about questioning technology and doing things with technology that were not possible in the past. So for me, creation is not about what colour is it — let’s talk about garments since we make a lot of those — it was never really about, what does the garment look like — it is, what would it mean to have a garment that moved on your body and moved in an uncomfortable way? What would it mean to have a garment that needs energy but doesn’t have batteries and needs to harness energy from the environment or from somebody else’s body. So for me that’s the creative aspect, and then being able to formulate that into a research question that leads to a successful research grant proposal. And then, working with a team that is very creative, so that the potential answers to these questions that we suggest can be described as beautiful or evocative or playful. And they do get invited to be shown in galleries and museums, which I guess is sort of the institutional stamp of approval for the creation side. I’m not an artist. I’ve never had a solo show as an artist. I really think of myself much more as a researcher. But a big part of my dissemination happens in museums and galleries.

So you wouldn’t consider yourself an artist, but you show in galleries? And your inspiration is not so much connected to the fashion, but connected to questions about technology?

Yes. Like how can we really break down what a garment is. Or what a textile is. And how can we use all of these emerging materials that are being used in aerospace or the automobile industries or whatever, but use them in garments. What kinds of new functionalities would they enable? New forms of expression. New ways of connecting with one another. But also, how would they help us understand the world in a different way? Question the world. The project Caption Electric and Battery Boy is really about questioning our dependence on energy and batteries and portables. The major point there was to create garments that are sort of ridiculous and uncomfortable. And the thematic that runs through it is one of fear and paranoia and fear of natural disasters and protection, so it’s deeply linked. And then in order for me to be able to raise the money that I’ve raised that’s more from the sciences and Engineering, there’s always a very strong scientific or engineering innovation in the project. And I would feel like a fraud if there weren’t.

Do you think with working on very highly funded projects, with industry and with big labels, do you see that as in any way compromising your vision? Or extending it? Do you find that working with big industries provides a positive constraint or something where you have to really compromise your creative work?

It’s a different kind of vision. I don’t see them as contradictory. The obstacle to work in my experience has just been the really kind of overwhelming bureaucratic aspect of administering large research grants at the university, where I ended up just spending so much of my money doing paper work and filing reports and filing expense reports in a thoroughly inefficient way… Industry can’t afford to have the same kind of level of inefficiency that we have in academia… They would go out of business. So that’s super refreshing. Of course then we have a board of directors that we have to answer to. We have to show a business model that would be profitable with an X amount of years. Whether that business model involves being acquired by Google or having sales or whatever, I mean that’s another questions, it’s the VC [Venture Capital] world.

That’s interesting, because usually we see the academy as the place where we can sort of nurture our bigger ideas and industry as a place where we have to compromise. But that’s not your experience?

It’s different ideas. But what’s really exciting is there’s different kinds of industry. And right now with the start-up culture around new technology, it’s all about innovation and wonder and discovery that, sure, you have to have a business model, but that can be viewed as a benefit rather than an impediment… I’ve also worked on projects with creative studios. So industry doesn’t necessarily mean military or medical devices. Industry can also mean Cirque du Soleil. Or working with PixMob, which is a great company, some of my ex students started it. So industry, sure, has to have a business model, and if it’s not profitable, it will go out of business, but it doesn’t mean you don’t innovate or you don’t do exciting work. And sometimes innovation is actually stifled in academia because of all the bureaucracy and paper work. I’m being provocative of course. Because all of the assumptions you’re bringing to that question are true, but there’s also that other side.

You said you don’t see yourself as an artist. What do you think the differences are between art and design?

Everybody is going to give you a different answer. But my answer these days is that art is about one individual and design is about multiple individuals. And of course people will argue with that and I will change my mind eventually, but that’s how I think about it these days. So for me, design fits a lot better into this research model where we have multiple authors for each project. It’s almost like thinking of the research work as a theatre performance, or a play, or an orchestra, where you have a conductor, but then everybody gets credited for their own role. Whereas I find a lot of the art research-creation, it’s still about the one person who takes credit for everything even though they might have a team of people working with them. But also for me design is perhaps a little bit more concerned with the tools, the materials, the processes, rather than like the final moment of showing the piece.

So in design there’s more of a process?

No, it’s not that there is more process, but the process is almost more important than the final piece, for me, okay. Whereas the way that I think of art is that the final artefact is given more importance, culturally. In design research, the process, the materials, the steps you took, are maybe just as important or even more important. And especially when you look at that whole movement of speculative design. Or critical design coming out of the UK, with people like Dunne & Raby. In fact, there isn’t really a final outcome, but it’s all about these trajectories and interrogations and asking “what if?” and showing these speculative processes. Or experimenting with materials. But not necessarily building up to the one artefact that will go into a permanent collection somewhere.

But say with industry you would need to eventually produce an artefact—

—Yeah, you need a product—

—Or else they would be like, “where’s your product”—

Well not necessarily, because also patents are a very viable outcome of industry work. So I’m writing a lot of patents right now with OmSignal. And those aren’t artefacts. That’s IP [intellectual property] that has a high monetary value.

In your work, for example in your Skorpions dress, you describe the dress as parasitic and the wearer as a host, so a lot of agency is given to the actual items that you create. Do you see what you do as somehow aligned with biotech? These garments are almost coming “alive”?

To me, a lot of interaction design I find problematic around the idea that the human is always in control or needs to always be in control versus the idea of giving up control a little bit. And maybe that’s also just a personal philosophy as well. With being a mother. Raising two kids in this very unusual sort of circumstance where I’m not their biological mother but I’m their full-time mother and yet I don’t have the same kind of control… So I think for me, my personal life experience has also influenced the way that I think about interaction design… It’s less about biotech and more about control.

It sounds a little like actor-network theory. We read this also in communication with Stewart Brand. And the fact that objects or technology can dictate the way things go, not necessarily just the human.

One of my favourite quotes from Sherry Turkle is that computers aren’t just a projective medium, but also a constructive medium [See Sherry Turkle, The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit (New York: Simon and Schuster), 1984]. You control or project your desires on them, but they also shape what your desires are.

So it’s a collaboration in a way between the human and the technology? And this is maybe freeing?

Well, the reason I can do these things is that I’m not in an Engineering faculty where each project has to be about solving a specific problem that is then quantifiably successful or unsuccessful. I can produce these projects that exist in this much more qualitative research space, whatever that means. I don’t have to have tables and graphs for each project that I make…. I don’t need to do those kinds of quantitative studies for my research, which allows me to explore these questions that are more — sometimes I say they’re poetic — I don’t have a very rigid theoretical structure for how I talk about these things. But it’s definitely great to have a freedom not to need a quantifiable result at the end of each project.

Is there anything about your lab that you would like to change or that you find problematic? Say, in terms of space?

When we were in that corner space on the 10th floor, that was too small. At one point if you can imagine I had about twelve people working in there with all kinds of sewing machines and electronic stations, so that was nuts. The thing that makes a space successful is to allow everybody to feel ownership over a portion of the space. You need everybody to feel like some small portion of it is their own. To develop a level of trust where people can leave things without worrying about them being either stolen physically or the ideas stolen, so actually working on a culture of collaboration and trust is really important. Definitely in my particular discipline where we need machines there’s always going to be the need to go to other spaces to use different kinds of specialized machines or facilities. But the space itself — it’s more about the culture you create in the space, about exchange, about giving, and the way that I fostered that from the very beginning is by having a lot of parties and 5à7s. It’s all about building trust.

All images taken from the XS Labs catalogue.

The post “It’s all about building trust”: An interview with Joanna Berzowska of XS Labs appeared first on &.

]]>The post The Media Lab as Space for “Play and Process”: An Interview with TML’s Navid Navab appeared first on &.

]]>The point is to build environments that are “not complicated but rich.” At the TML, we live with our designs, within our responsive environment.

Interview with Navid Navab

Associate Director in Responsive Media, Topological Media Lab

Research-Associate, Matralab

Multidisciplinary Composer

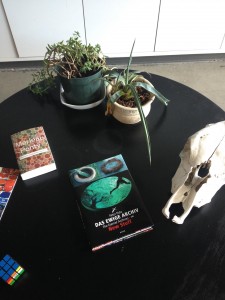

The Topological Media Lab (TML) is a large, open space with polished concrete floors and a long wall of windows punctuated by various hanging plants and black-out curtains. The room is canopied by a maze of light bulbs, microphones and wires that dangle from the tall ceiling, all of which goes unnoticed if your eyes are preoccupied with the other strange and wonderful objects that inhabit the lab – on one low coffee table, a deer skull sits nonchalantly next to a Rubik’s cube and Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception.

The first time I attempt to locate the TML, I find myself wandering through the shiny halls on EV 7, pondering the chaotic numbering systems of the future. Lucky for me, Navid Navab – multidisciplinary artist, “media alchemist,” thinker/maker – embraces chaos (and knows these halls well). Navab, who is also Associate Director in Responsive Media at the TML, kindly fetches and leads me to room 7.725, the space where he works, researches and creates. We speak at length about the design and philosophy of the lab, as well as the various projects that have been explored there, and are eventually joined by Michael Montanaro, co-director of TML and chair of Contemporary Dance at Concordia. The conversation is both delightful and at times mystifying. I begin to jot down terms like “gesture bending” and “subjectivation,” planning to Google them later…

The dance/new media projects that have emerged out of TML are what first piqued my interest in the lab. The “Shadows and Light” sequence in TML’s Einstein’s Dreams (2013) presents a space in which performers interact with media as they move through the space, “dragging” pools of light with their bodies as they dance. Another example is performer/creator Teoma Naccarato, whose past research with TML has contributed to her practice, which integrates contemporary dance with interactive video, as well as audio and biosensor technologies to navigate material and virtual scenarios.

Several weeks after speaking with Navid and Michael, I decided to ask a few more questions, via email. Navid’s writing style is almost identical to his mode of speaking; he meanders deftly and with charm between topics as diverse as teamwork, dance improvisation, operating theatres for surgeons, grant-writing and Felix Guattari. Because of this, I’ve provided a glossary of terms at the end of the interview to help readers navigate.

Here’s what Navid had to say:

HB: What is the Topological Media Lab?

NN: The TML (Topological Media Lab) was established in 2001 as a trans-disciplinary atelier-laboratory for collaborative research-creation. In 2005, TML moved to Concordia University’s Hexagram research network. Following the departure of the founding director Sha Xin Wei in 2013, the TML was restructured to sustain as an autonomous laboratory for the critical study of media art and sciences at Concordia University.

As articulated on our website, TML’s projects serve as case studies in the construction of fresh modes of knowledge, bringing together practices of speculative inquiry, scientific investigation and artistic research-creation. Currently, TML’s technical research areas include: responsive environments, active media, computational-materials, and gesture bending. Its application areas lie in movement arts, speculative architecture, and experimental philosophy.

The TML is both an atelier and a laboratory for research in improvisatory gesture from both humane and non-anthropocentric perspectives. Our atelier research investigates the process of subjectivation, agency and materiality from phenomenological, social and computational perspectives. It approaches this by suspending assumptions about what we think are egos, humans, machines, objects, and subjects. Instead, we consider the transformations of things, and see how these things emerge through play and process. This method is informed by a continuous (rather than tokenized object/grammar-based) approach to material change, hence the “topological” aspect. Topology is concerned with the non-metric (non-numerical) properties of space and the continuous, dynamic relationships through which space is constituted.

HB: How did you originally become affiliated with TML?

NN: I first become affiliated with the TML in 2008 as a curious student — occasionally dropping in, apprenticing with inspiring thinker-makers — and shortly after as a core artist-researcher and co-author of projects. I was given sufficient autonomy to freely innovate my own voice and in a few years I was initiating and leading multiple research streams of my own. Each research stream would investigate a particular question or phenomenon that interested me, which I would explore through organized discussions, intensive material-computational research-creation, and eventually through live experiments, workshops, engineered software environments, published works of art, and peer reviewed publications. The studio-lab supported these diverse activities both intellectually and logistically, thus enabling my pursuit of passionate and radically fresh art-research without having to constantly defend these investigations in institutional language (e.g. of disciplines, granting agencies) or in terms of the market.

Over the years my activities have enriched and shaped the environment of TML, leading to my role as Director in Responsive Media, in collaboration with the lab’s current co-director Michael Montanaro.

HB: How many other people are involved regularly at TML?

NN: TML welcomes curious passersby to drop in and engage with its ecology of practice. TML’s long-term research-experiments are driven by a small group of 6 or 7 actively present members: directors, administrators, core artist-researchers, and research-assistants. We are also in constant exchange and collaboration with our international partners at top institutions and centres around the world. Additionally, TML hosts a continually shifting and returning array of newbies, apprentices, students, artists in residence, visiting scholars, international partners, artists and hackers.

HB: What are the practices that happen at TML on a daily basis? How does knowledge emerge out of the TML and what is the material form of that knowledge?

NN: Practical domains for art research at TML are:

theory: imagine, make, explore, articulate and evaluate concepts rigorously

art: ethical-aesthetic gesture and creative ways of being with others

technique: (for) collective innovation, improvisation, and play

The TML stores group knowledge, an apparatus structured by ongoing experiments, from which members take what they need in order to make experiments, and to which they contribute pieces that others can use in the future. The apparatus is made up of various components such as physical things, material samples, software, documentation, videos, reports and procedures.

The TML is not a production facility for individual art projects.

It is a place for building sketches and experiments with larger ambition for impact, and which requires the collective talent, expertise, and energy of a small team. The TML is a nexus for art-research (neither art production nor technology development) with a family of themes with philosophical or critical value such as:

– ethico-aesthetic play

– distributed agency

– materiality

– gesture and movement

– phenomenology of performance

– critical studies of media arts and sciences

These themes are elastic and have evolved over the years around the joint interests of an affiliate community of artists, researchers and philosophers who engage with the lab. These themes also take material form, as works of art, performances, engineered instruments or systems, essays, peer-reviewed papers and documentary videos.

Besides making stuff and overseeing research experiments, we also situate TML’s activity within the contemporaneous global context, and locate funding for our affiliate researchers so that individual members can pursue their work with more autonomy and freedom. In exchange, we expect work of world class quality (not student class project work) which should aspire not merely to tech art venues (such as Ars Electronica), but also to real world, socially embedded situations.

HB: How does the material space of TML affect the products and processes that occur within the lab?

NN: Some of TML’s experiments use active lighting and acoustic conditioning systems to change the apparent physical qualities of interior or exterior space. The point of this work is to build environments that are, to quote Xin Wei Sha, “not complicated but rich.” The TML space was designed from the ground up by the founding members, Sha Xin Wei and Harry Smoke, to handle demanding and diverse sets of events and technological structures. The configuration of the space is itself continually shaped under ongoing research. At the TML, we live with our designs, within our responsive environment. Our research-creations are thus always put into unscripted play and place. This approach results in responsive designs that at once address everyday functions, inform ambient aesthetics and enable virtuosic improvisations, all within one holistic, responsive environment — the TML itself.

Our designs and concepts are not invented in a “black box” and they are not made with black-boxed technologies; they are co-articulated through TML’s ongoing dynamic and spatial apparatus that is never turned “off”: a responsive environment full of rich contingent activity.

Therefore, the space at TML is itself a live apparatus for enacting knowledge in a collective fashion. Projects conducted in the atelier draw on and also contribute to ongoing research in the computational and natural sciences, seeking to understand the dynamic interplays of social, psychical and material space.

(Consider Navab’s delightful description of the “ecology” of the Topological Media Lab in the imagined scenario below)

…a visiting person’s shy manner of walking into TML gently perturbs our responsive ecology—very much the same way a lost traveler’s careful steps in an autumnal forest perturb the surrounding life, resulting in fields of distributed activity. A few researchers and artists are busy making stuff and a group of people at the far corner of the lab are participating in a seminar. Through the responsive environment, the inhabitants of TML are gently made aware of a different-presence in the lab and yet this awareness—this ambient behavioural resonance—does not cost their full foci of attention. One research assistant walks to the new comer to welcome them into the space….

HB: What is the difference between the Topological Media Lab and the other space where you are affiliated, the MatraLab?

NN: TML and Matralab occasionally collaborate on projects, share talent and often support each other in large-scale initiatives. Despite their partnerships and similarities, the two labs are however completely independent of one another, each with their very particular and unique vision, process and agenda. Matralab is a research space of inter-x art directed by Sandeep Bhagwati, “dedicated to using interdisciplinary art practice to bridge the gap between emerging art forms and their aesthetic reflection.” Matralab’s core activities revolve around experimental musical events, and comprovisational environments to name a few. Matralab’s research is leading to the establishment of a practical and theoretical framework for the creation and evaluation of interdisciplinary, intercultural, intermedial and interactive art.

HB: How important is dance/movement to the work done at TML? I know you work with dancers regularly – can you talk briefly about what it’s like to collaborate with dancers?

NN: One of TML’s strategic goals is to transpose insights from movement and performance into the design of durable, everyday situations, and experimental environments. We leverage our pre-verbal intuition of physical materials and embodied knowledge to explore the ways in which bodily relations are felt and understood. For example, we do experiments that explore when movements can be regarded as volitional rather than accidental, and when movements—perhaps among multiple bodies and things—can be regarded as a single gesture. The emphasis is often on continuous, unanticipated movement that may be improvised freely by those within the conditioned space.

Our ongoing GestureBending* experiments explore how everyday gestures can become charged with symbolic intensity and used for improvised-play.

Close collaborations with dancers and performers are extremely unique and precious opportunities for rigorous co-creation, refinement, and embodied evaluation of gestural media and responsive environments.

What is evaluated is the media/matter/environment’s potential for play—in its ability for allowing boundlessly open sets of a priori gestures and experiences by the participants to acquire expressive, playful and poetic force. If successful, participants’ gestures not only lead to unexpected meaning and instrumentality but to narratives about and recognizing daily life and the material world as a platform for play and for refined practice. Such a design approach allows for any potential movement at all by the participants to turn into a potentially co-expressive art-event. This removes the burden of modeling the human experience through mimetic performativity and instead allows for such notions as gestural meaning, intentionality, expressivity, noise, musicality, and even performer, performed and spectator to freely arise from the context established in the moment of performance.

So in a sense—to maximize improvised co-expressivity and synergetic play— it is helpful for performers to unlearn presumptions about what it means to interact with responsive media and instead maneuver embodied intuition, to improvise gestures as they already always have in continuous media like fabric, flesh, water, air, and mud. When designing performative media (an installation, instrument, or a responsive scenography), even when rigorously staging theatrical events with virtuosic performers, who are welcome to incorporate or invent their own very unique sets of gestural vocabularies, we maintain the position to never model or presume, at least in our design metaphors, what constitutes a gesture or a body. We condition performative events that potentialize improvised play, always working with a priori non-anthropocentric movement and contingent activity. Therefore solo dancers, groups of passersby, and even non-humans objects and subjects are all treated (computationally and conceptually) as fields of stuff and process. Within this continuously responsive field—fusing humans, non-humans, media, matter, and energy— solo dancers as well as other (non)human performers can improvise nuanced gestural expressions, co-constituting and enacting one another in the ever-changing field that forms them!

At TML’s recent GestureBending workshops, resulting from my ongoing collaboration with expert dancers, participants discovered that their everyday movement can create intricate sonic textures and developed their own unique vocabulary of sound generation to sculpt musical events via intuitive movement and embodied engagement with computationally enchanted materials. Leveraging the GestureBending apparatus, renowned TML performance works such as Practices of Everyday Life | Cooking symbolically charge everyday actions and objects in ways that combine the composer’s design with the performer’s contingent nuance.

What we are suggesting is a holistic shift from representational technologies to performative media, from nouns to verbs, from objects to fields of matter-in-process, from a priori concepts to processes that enact concepts. To adapt Mcluhan, instead of encoding and decoding a presumed message we are enchanting the medium!

I chose to close my interview with a question about dance because I am fascinated by the potential that interactions with new media hold for dance and the moving body, and I know that TML is also intrigued by these collaborations. When Navid explained GestureBending to me in person, he flung his left arm out into space and asked me to imagine a sound that followed from the movement of his body, unexpected, off in the distance, as if resulting from his thrown arm. A performer improvising amidst a soundscape such as this would be affected by the sounds their own body was “producing,” thus enlivening their own improvisational impulses. With GestureBending, sound (or light, or some other vibrant force) is shaped by the dancer (controlled by their movements) and likewise the dancer’s movements are shaped by the elements that interact/play with their body. The space of the Topological Media Lab, with its hung lights, mics and sensors, and its smooth, clear floor, perfect for movement through space, is an ideal space for this type of improvised “duet,” a fact which underscores the importance of built space to the forms of knowledge that can emerge out of the lab.

Glossary of Terms:

Topology: A mathematics term for the study of open sets in which a given set is a “topological space.” Topology is developed out of geometry and set theory and is interested in the the deformation, stretching, transformation and bending of space and dimensions through a concept of connectedness. For example, “a circle is topologically equivalent to an ellipse (into which it can be deformed by stretching).”

Subjectivation: A philosophical term/concept invented by Michel Foucault and explored further by Deleuze and Guattari which “refers to the construction of the individual subject.” Also corresponds to Althusser’s concept of interpellation and is sometimes called “subjectification.”

Gesture Bending (Navab’s definition): A generic term coined by Navab, which refers to the poetic transformation and enrichment of gestures through instrumental augmentation or technical mediation of movement. The goal is to continuously enact persuasive conditions for the transformation of networks of meaning production in the embodiment of movement. Pervasive Gesture Bending can potentialize improvised-play, leading to emergence of conditions that could invite performers to synergistically improvise with a hybrid expressive force.

Speculative Architecture: This book review may help to define this complex term.

Black Box Systems: A device, system or object which is defined by its inputs and outputs without consideration or knowledge of its inner workings. This term is most often used in science, computing and engineering, and can be applied to many objects, like a transistor, an algorithm or even the human brain.

Comprovisational: Navab’s term for compositional techniques used to explore blends between fixed composition and free improvisation with interactive performance systems.

Ethico-Aesthetic Play: Navab uses this term to adapt Guattari’s concept of the coming into formation of subjectivity (or Subjectivation, above), through an engagement in art, dance, performance and improvisation. In Xin Wei’s words, “to conduct philosophical speculation by articulating matter in poetic motion, whose aesthetic meaning and symbolic power are felt as much as perceived.”

Find out more about the Topological Media Lab on their website.

The post The Media Lab as Space for “Play and Process”: An Interview with TML’s Navid Navab appeared first on &.

]]>The post Navigating Interdisciplinary Digital Media Labs: An Interview with Erica Lehrer, Director of CEREV appeared first on &.

]]>By Sabah Haider

In this interview for the graduate seminar HUMA 888: Mess and Method [Fall 2015, “What is a Media Lab?” edition], Sabah Haider, PhD Student at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Society and Culture at Concordia University interviews Dr. Erica Lehrer, Director of CEREV and Associate Professor, History and Sociology and Anthropology (joint-appointment), and Canada Research Chair in Post-Conflict Memory and Ethnography & Museology, at Concordia University. In this interview, Haider seeks to gain insight from Lehrer on how interdisciplinary research engages with technology and the fast evolving Digital Humanities.

EL: First of all, I should begin by saying that CEREV is in the process of separating itself from our lab space, which itself is being renamed the Centre for Curating and Public Scholarship. I didn’t want my own preoccupations with difficult, contested histories and cultural issues to dominate a lab space that could be accessible to many more users who share my concerns with using exhibition or curatorial work as a form of public scholarship. So in the future CEREV will be one of a number of units and groups of people using the CCPS lab platform. It was also a question of stability. There is no lab work without lab funding supporting lab staff, and the model we had was too narrow to be financially sustainable.

SH: The Centre for Ethnographic Research and Exhibition in the Aftermath of Violence (CEREV) is a media lab that fosters the intersection of many disciplines/disciplinary approaches to produce broader understandings and to challenge existing understandings around ideas of the exhibition of trauma and violence. On the CEREV it states the centre was established “to create a community of researchers and curators and produce new knowledge around issues of culture and identity in the aftermath of violence.” In relation to the practical side of this — how can you describe or explain how knowledge is produced at CEREV?

EL: Different kinds of knowledge are produced at different nodes in the network of sites and people that make up CEREV. We have an incubator room with computers, and more importantly a round table, where postdocs and students (and sometimes me) meet and talk; we have our exhibition lab, where curatorial experiments and public presentations take place; periodically we have large-scale public exhibitions at various local or international sites; we meet in homes or cafes or my office for more casual mentoring chats; and then we have our website and Facebook page. These are all parts of “the lab,” and the spatial aspect is centrally important to what kind of knowledge is produced, and who participates in its production. I would say that knowledge is produced individually in reading, looking, and thinking; it is produced socially in interdisciplinary, multi-level, and inter-subjective dialogue, negotiation, constructive mutual challenging (sometimes uncomfortable), and in shared experience among differently positioned people; it is produced in a process of making, building, and experimenting with various media; and (for those who only come into contact with things we produce) I hope knowledge is produced in inspiration and the generation of new ways of thinking and seeing. For me the key to “lab-ness” is the special process of collaborative creation – we all help each other to think through and envision a product even if it ultimately is put out into the world under a sole author. I’ve always liked (and used) Gina Hiatt’s manifesto, “We Need Humanities Labs.”[1]

SH: How does CEREV engage with digital technologies to stimulate this? Since the lab’s creation in 2010, has there been an increasing interest in also exploring relevant digital forms and practices, in parallel with the growth or expansion of the digital humanities (DH), particularly as the DH has spawned a seemingly infinite number of digital tools that facilitate new types of exploration?

EL: Playing with new technologies can generate ideas, and that’s why we have our indispensible Director of Technology, Lex Milton, who crucially has a background in educational technologies. He’s an excellent muse, who can listen to logo-centric humanities scholars and help them think about how they might expand and “curate” their projects in productive ways by imagining what technology can do. But I’m not so compelled by projects that use technology as a starting point – or perhaps I mean humanists are not best-positioned to start from everything that “can be done” and then try to figure out how to use XYZ bells and whistles in their own work. Rather I think we do best when we have a particular problem we want to solve – like getting multiple voices or perspectives visible/audible around an object, or getting people who are far away from each other into dialogue, or creating options for accessing and exploring massive archives of information in a single space, or moving people emotionally – and then thinking about what might help us do that. This is when dialogues between humanists (or social scientists) and people with technical and creative skills are most productive. We dream aloud, we share our challenges, and they suggest possible solutions using the technologies that exist. And we humanists push the tech people by asking them “do you think you could make it do XYZ?” It’s a really exciting dialogue, and the final products are always something neither party could have envisioned on their own. We stretch each other.

SH: What are some of the emergent media forms that the lab has incorporated/is incorporating? How can you describe the materiality of the CEREV space? (i.e. mobile, virtual, etc.) What kinds of material forms (i.e. forms of output) does the knowledge produced at CEREV take? What types of ethnographic experimentation has/does CEREV facilitated/facilitate?

EL: I alluded to the various materialities linked to the CEREV lab above. We do have a couple of dedicated physical spaces, and the exhibition lab in particular has a lot of technical tools – projectors, mobile screens (some of them touchscreens), iPads, surround sound capability, etc. – as well as analog ones like pedestals and screens and curtains. And then lots of recording equipment for still image, video, and sound. We facilitate whatever kinds of technology-enhanced fieldwork people want to do, which includes documentation as well as bringing various pre-produced media to field sites, or to co-produce media with various research interlocutors. The forms of output range from ideas to lectures, blog posts, scholarly publications, videos, and exhibitions.

SH: Most of the work of CEREV affiliates appears focused on themes of meaning, affiliation, curation and exhibition. Trauma and suffering, as you have identified, encompasses victims, perpetrators and bystanders or observers. Has/does research at CEREV explored/explore all three of these perspectives/positions — or relationships between them?

EL: I would say yes, we’ve created work looking at these positions and their interrelations. PhD student Florencia Marchetti has been creating field-research-based videos made at a site of a former detention and torture centre in Argentina, which she then uses to seed discussions among the people who today live nearby – some of them were bystanders at the time the centre was operational and they are bystanders to memory today. Students re-curated the video testimony of a Montreal Holocaust survivor to explore victim narratives and their forms and uses. And my own work has dealt with how to raise difficult questions that implicate audiences in their own collective “perpetrator-hood” regarding historical violence and its contemporary legacies or ongoing prejudices. These are just a few projects but they cover all the positions you mention.

SH: What does it mean to have this kind of space as an interdisciplinary scholar — a ethnographer/historian/anthropologist?

EL: It’s mostly challenging. It makes one realize how comfortable text is – both in terms of the limitations of creating it and its relatively limited reception. When you have to deal with capturing and transmitting so many more dimensions of experience, and when such a large public audience can respond (and challenge) what you create, one is confronted with the limitations of one’s own view.

SH: Has anyone outside of your research community (i.e. from the wider “at large” community taken interest in your space, and if so why and how?

EL: Yes, people from various communities, like the Black community in Little Burgundy, or members of the Armenian, Palestinian, and Jewish communities, as well as AIDS activists are just some of the groups that have seen in the lab a space to gather to create and debate representations of history and culture relevant to their own groups. You can read a bit more about the projects we’ve done in the lab, and my own trajectory, at: http://cerev.cohds.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Abell-interview-with-EL.pdf

// END

[1] Hiatt, Gina, “We Need Humanities Labs”, Site URL: <https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2005/10/26/we-need-humanities-labs>

FOR A FULL PDF OF THE INTERVIEW CLICK BELOW

HUMA 888 Interview_CEREV_Erica Lehrer_by Sabah Haider

The post Navigating Interdisciplinary Digital Media Labs: An Interview with Erica Lehrer, Director of CEREV appeared first on &.

]]>The post BFC – BigFriedChicken’s Cook and Sort machine appeared first on &.

]]>BFC – BigFriedChicken’s Cook and Sort machine

How does the BFC Vanilla edition sort cooked chicken, feathers, and eggs into specific chests?

An industrial cooking and sorting machine. This device is the soul of the BFC and automates the process of collecting, cooking, sorting and finally storing cooked chicken, feathers, eggs and any anomalies (ie: dirt blocks, uncooked chicken, etc) into containers (chests).

To begin the process, the chicken brood is enclosed over hoppers (in our case, 3), these hoppers are placed so that they output towards the next hopper in line, with the final hopper output dropping down into a dispenser.

The dispenser will not shoot out eggs unless it is powered.

The mechanism that powers the dispenser is a circuit designed to launch eggs once they enter the dispenser through the hopper chain. The circuit uses a comparator in the “compare signal strength” mode in order to compare the state of the dispenser with the feedback signal to detect incoming eggs and to power the dispenser to fire them.

In “compare signal strength”, the comparator is off but

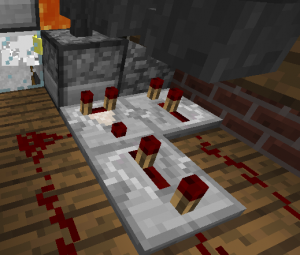

and so it is important that the comparator is properly configured so that its rear input faces the dispenser’s rear (figure 1).

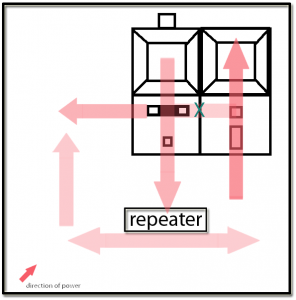

Figure 2. The arrows show the circulation of power. The comparator will try and compare values on either side of it but cannot compare the repeater on the side because its power follows a linear tract. The X shows that the connection is not established and therefore ignored.

When there are objects in the dispenser, the comparator will compare that amount to its side inputs, these being red stone wire and a repeater. The comparator does not compare the signal to the repeater because the repeater’s output does not face the comparator (figure 2).

The comparator compares the value in the dispenser to the red stone circuit to its left. A repeater, its input towards the comparator, controls the rate at which the signal passes through the red stone circuit to ensure that the comparator’s signal does not instantaneously turn on the red stone wiring. This ensures that the comparator’s signal will be stronger than the red stone circuit.

Ex: if the dispenser has one egg, the comparator has a value of 1. It checks it’s side inputs and the red stone circuit will have a value of 0. 1 is bigger than 0, and therefore the Comparator turns on.

In the second example, I explain one of the reasons for using a repeater directly after the comparator. Although not necessary, the repeater ensures that the red stone does not instantaneously power on when the comparator does.

Ex 2: the dispenser has one egg, the comparator has a value of 1. It checks it’s side input and server lag or a malfunctions, and because the system does not have a repeater to delay the signal, its value also appear as 1. 1 is not greater than 1 and therefore, no power. Without power, the dispenser does not do anything.

When the comparator turn on, a signal passes through the repeater, which delays it by a fraction of a second, and circulates both left and right on the red stone circuitry. On the left, the signal powers the red stone adjacent to the comparator and powers the red stone to 1. As we have seen, when the comparator and the red stone next to it have the same value, the system turns off.

Simultaneously, the right side powers a repeater, that powers a block which in turn powers the dispenser which shoots out the object (egg). By shooting out the object, the dispenser value decreases and as a result the comparator turns off.

There is no danger of overflow of eggs into the dispenser because the hoppers only ever allow one item to transfer at a time. This ensure that this system constantly turns on and then off for each egg.

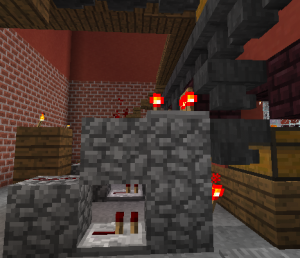

The dispenser shoots the eggs into an enclosure to produce chicks and from them, cooked chicken. The eggs are launched into an enclosed chamber over a hopper with a half slab, some hatch as chicks. The chicks are therefore elevated above the regular block level and only have a half slab area to circulate. Since chicks are only half a block high, they can move freely. A full block above the hopper, contains lava produced by a dispenser (figure 3). This dispenser is powered by toggling a button – while ON it produces the lava, and OFF it retracts the lava. Since a fully matured chicken is a block in size, once the chicks grow up, they surpass their half slab of livable circulation and the lava cooks them. In most cases the dropped item, cooked chicken and feathers, will fall through the half slab and into the hopper underneath it which is positioned with its output towards a chest. In some cases, the dropped item will burn.

A row of hoppers aligned with their outputs towards the next in line, lies beneath the chest (figure 4). The hopper pulls the items out of the chest and down the conveyer belt. The last hopper at the end of the belt has its output leading down into another hopper that leads down and into a chest. This chest, at the end of the line, will collect any surplus items that are not configured in the regular sorting system.

Figure 4. The conveyor belt hoppers each have their output leading towards the next hopper. This ensures that items move fluidly.

Figure 5. Conveyor belt hoppers, sorting hoppers, and chest. Note that the red torch is ON, at the bottom, to indicate that the hopper is locked and will not pass down items.

Beneath this conveyor belt of hoppers are three evenly spaced red stone sorting circuits designed to store specific items into their respective chests. The system works by taking advantage of a hoppers ability to lock when powered and to draw similar items within its inventory and use it to power red stone. In this way, when items travel through the conveyer belt, specific items (in our case feathers, chickens and eggs), will fall down into a lower hopper when they match (figure 5).

Hoppers work by shifting items in it towards its out put. In the assembly line, the items are pushed left, but, if there is a hopper underneath a hopper, items will fall down. When a hopper is empty, any items may travel through it, such is the case for the last chest on the conveyer belt. This chest collects any material our three configured hoppers will not collect. These configured hopper’s slots have been filled with 21 sticks and one chicken/feather/egg which is located in the first slot.

When a hopper’s slots are filled, it will try and collect additional material first through the first slot. For the sorting machine to function properly, one chicken (or desired item to be sorted) must be at the beginning of the slot line so that the hopper will constantly look for it. This hopper is specifically designed to allow only one item to travel through it (and into the next hopper below it which deposes it into a chest) at a time. This ensures that the sorting machine will never collect any sticks, but always the primary slot item.

Figure 6.

Just in case,

ex: 1 chicken, 6 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks (figure 6)

One chicken from the conveyer belt falls down into this hopper: 1 new chicken + old chicken = one chicken falls down into the lower hopper and into the chest before the hopper locks again (I will explain that process shortly). We still have 1 chicken, 6 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks and therefore the sorting machine will continue looking for chickens and not sticks.

Alright, so we now understand that the cooker function with a “compare signal strength” comparator coupled with repeaters to launch eggs into an enclosure that will hatch chicks that will cook when they mature into chickens. The cooked chicken then falls into a hopper located under the enclosure, into a chest, and then is sucked into the hopper conveyer belt which will then sort them into four categories: chicken, feathers, eggs and everything else. But how does the sorter work? Where does it obtain its power and ability to transfer only one item at a time down from the sorting hopper into the lower hopper and into the chest? Why don’t all the items in the sorting hopper (1 chicken, 6 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks) not fall down also? The answer, a comparator and repeater process again.

Figure 7. The comparator is on “Measure block state” mode. Out put towards the red stone wire. It is difficult to see, but sparks are coming out of the first block to show that it is powered. The second block of red stone wiring is not sparking.

Instead of using a “Compare signal strength” (CSS) comparator as we did with the cooking section of the BFC, the sorting area utilities a “measure block state”(MBS) comparator and its output facing two blocks of red stone wire (our circuit material). Unlike the CSS, the MBS “will treat certain blocks behind it as power sources and output a signal strength proportional to the block’s state.” This allows the user to control how many items fall into the lower hopper, and ensures that the sorting hopper does not empty itself out into the lower hopper. But how?

Alright, so the hopper is locked using a red stone torch set ON. The comparator has only enough power to power ONE of the red stone wires (figure 7). When one cooked chicken falls down into the sorting hopper, the additional power of one chicken will power the second red stone wire block, which will activate the repeater that will turn off the RED STONE TORCH long enough to allow one item to fall down into the unlocked hopper before locking again. The repeater ensures that only one item falls down at a time so that the sorting hopper does not empty itself out.

How does the comparator generate energy? Why does it only power one block when we have 1 chicken, 6 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks, but two blocks when there are two chickens?

It is not readily obvious how this works, but a member of the Minecraft Wiki community shared this mathematical formula to explain how to calculate signal strength from any given item.

signal strength = truncate(1 + ((sum of all slots’ fullnesses) / number of slots in container) * 14)

1 + ((sum of all slots’ fullness)/number of slots in container) x 14 = amount of red stone blocks that will be powered.

To begin, we must calculate the amount of items in our hopper and divide each by their full amount. In our case, the items we are using all stack up to a maximum of 64.

1/64 + 6/64 + 5/64 + 5/64 + 5/64 = 22/64

22/64 = 0.34375

0.34375 divided by amount of slots in a hopper (5) = 0.06875

0.06875 x 14 = 0.9625

0.9625 + 1 = 1.9625

Truncate this number and we get 1

therefore, this formula powers 1 red stone block.

It is important that the non-truncated number is 1.9625 because with an additional chicken, the truncate is 2.

22/64 + 1/64 = 23/64

= 0.359375

= 0.071875

= 1.00625

= 2.0624

truncate 2

With the second block powered, the repeater turns off the torch long enough for one chicken to fall down into the chest and return the power to 1. The sorting machine absolutely needs two blocks powered for items to fall.

Why not use other items such as signs that stack up to 16?

Using signs or other items that stack up to 16 actually impede the machines functionality:

ex: 1/64 (our chicken) + 2/16 + 1/16 +1/16 + 1/16

1/64 + 5/16

0.015625 + 0.3125

= 0.328125

= 0.065625

= 0.91875

=1.91875

= Truncate = 1.

BUT, if you add an additional chicken:

2/64 + 0.3125

= 0.34375

=0.06875

=0.9625

= 1.9625

truncate = 1

Not enough power.

Therefore, using items that stake up to 16 will decrease the amount of cooked chicken gained as this system would need 3 or more chickens before having enough power to let one pass. The other system ensures that the user has the most cooked chicken gain.

Why not add more signs? Adding just one additional sign will power two blocks and thus render the sorting machine useless as everything would empty out of the hoppers (as the constant power will allow the repeater to keep turning off the red stone torch and letting more items down into the chest). Using this energy, the system is able to collect cooked chicken and other material and place it into specific chests.

Have fun with your BFC

http://minecraft.gamepedia.com/Redstone_Comparator

The post BFC – BigFriedChicken’s Cook and Sort machine appeared first on &.

]]>The post The ‘Pataque(e)rical Imperative appeared first on &.

]]>How do deviations from the norm provide an important foundation for radical invention and improvisation in contemporary poetry? Acclaimed poet and scholar Charles Bernstein makes a strong case for the importance of the exception.

Bernstein’s talk explores how the process of swerving away from expected trajectories is necessary for radical improvisation and the invention of new poetic forms. With special reference to Wittgenstein’s use of “queer” in Philosophical Investigations, he makes a strong case for the value of aesthetic positionality as part of the overall program of ’pataphysical disciplines such as Midrashic Antinomianism and Bent Studies.

Introduction by Darren Wershler

Recorded by Michael Nardone

Concordia University, Montreal

25 October 2012

The post The ‘Pataque(e)rical Imperative appeared first on &.

]]>The post Plucking Fluxes appeared first on &.

]]>Plucking Fluxes: Media Archaeology to the Metal

Matthew Kirschenbaum

This talk adopts a media archaeological framework for considering the floppy disks (the ubiquitous remnant of the first great home computer age) and their virtual simulacra, the disk image. The conceit of an “image” confers a complex epistemological status, bearing the inheritance of centuries of Western philosophical thought about the nature of mimesis and representation, with concomitant implications for archival notions of evidence, authenticity, and integrity. We will therefore descend to the ferro-magnetic surface of this unique class of media objects to examine their import and legacy from both a technical and theoretical standpoint.

Introduction by Darren Wershler

Recorded by Michael Nardone

Concordia University, 20 March 2013

Link to Matthew Kirschenbaum’s site:

mkirschenbaum.wordpress.com

The post Plucking Fluxes appeared first on &.

]]>The post Between Blankness & Illegibility appeared first on &.

]]>Lisa Gitelman and Craig Dworkin in dialogue

Moderated by Darren Wershler

Concordia University, 20 January 2013

Recorded and transcribed by Michael Nardone

Darren Wershler:

Thank you. Welcome to the Concordia Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Society and Culture’s panel on the materiality of paper in print.

Gerald Graff has remarked that given that intellectual history consists entirely of a series of conversations and arguments, it’s all too seldom that we stage events where scholars actually talk to one another in person. So it’s especially exciting to be able to bring to you today a discussion between two people whose work is so vital and influential. Intellectual conversation has almost always been asynchronous. We discuss and debate the matters that concern us with people separated from us by time and space. Historically, the medium enabling that discussion has been paper. So, it’s particularly appropriate that the materiality of paper, including the various formats and genres of blankness, is what’s under discussion here today.

China Mieville’s The City in the City is a detective novel that takes place in two distinct cities that occupy the same physical space, but whose inhabitants have been rendered incapable of acknowledging each other through the function of competing ideologies. Hanging over everything is the nagging feeling that the ideas and opinions being expressed nearby could profoundly effect what we do and how we do it if we could only access them.

I first began to think about the potential for a conversation between Lisa Gitelman and Craig Dworkin when I realized that although there current research object, the blank – blank books, blank paper – was the same, that they viewed it in a kind of parallax: Gitelman from the perspective of media history and material media theory, and Dworkin through the lens of contemporary conceptual poetics. Each perspective has something to offer the other, as well as its own blindnesses. But the subtle and not so subtle regulatory mechanisms of the academy often prevent us from even realizing that somewhere nearby, perhaps even on the same floor of our building, another conversation about the objects, institutions, and discourses that matter to us, may well be occurring.

I’d like to believe that it shouldn’t require moments of profound disruption in the dominant circuits of communication to make us realize such possibilities, though, both the anti-SOPA website blackouts on Wednesday and yesterday’s revelation of the draconian end-user license agreement terms for Apple’s iBook’s author application have made me think a lot harder about the materiality of blankness this week than usual. It is in that spirit that I’d like to introduce our speakers for today.

Lisa Gitelman is a leading scholar in the field of media history and an associate professor of English and Media, Culture and Communication at New York University. Though much of her research concerns American print culture and techniques of inscription, Gitelman’s work also makes a major contribution to digital media studies. It insists on the importance of method, tracing the patterns that render digital media meaningful within and against the contexts of older forms. All media, she has famously observed, were once new media. She has elaborated on this concept from Scripts, Grooves, and Writings Machines: Representing Technology in the Edison Era through to New Media: 1740 – 1915, her edited collection with Jeffrey Pingrey, to her most recent book Always Already New: Media History and the Data of Culture. Her current projects include a monograph, Paper Knowledge, and an edited collection, “Raw Data” Is an Oxymoron. For the past three weeks, Lisa has been the Beaverbrook Media at McGill Visiting Scholar. We’d like to thank Media at McGill for helping us to make today’s event possible.

Craig Dworkin is a founding figure in contemporary conceptual writing, the editor of the Eclipse digital archive, and a professor of English at the University of Utah. Since his first monograph, Reading the Illegible, Dworkin has been an incisive theorist of the limit cases of contemporary poetry and poetics, which is not entirely surprising because several of Dworkin’s other books, such as Parse, constitute the limit cases of contemporary poetics. For those of you who haven’t seen it, Parse is the result of taking Edwin A. Abbott’s 1874 text How to Parse and attempt to apply the principles of scholarship to English grammar and analyzing it according to Abbott’s own system. It is among the most unnerving books that I have ever encountered, which is saying something. Dworkin’s edited collections include the brick-sized Against Expression: An Anthology of Conceptual Writing, with Kenneth Goldsmith, The Sound of Poetry / the Poetry of Sound, with Marjorie Perloff, and Language to Cover a Page: The Early Writings of Vito Acconci.

How we’re going to structure this is we’ll begin with each of our speakers talking for about 15 minutes, then we’ll proceed to about another half hour of conversation between them, and then on to general questions. So, we’ll begin with Lisa Gitelman.

Lisa Gitelman:

Thank you, Darren. Thank you, Marcie. Thanks, too, to Craig, and also again to Media at McGill. It’s been great to be here in Montreal.

Maybe just one more second of background before I launch into my allotted 15 minutes. Darren read chapters by Craig and I that each have to do with blank books, and we’ve read each other’s chapters, and we’re not going to present the full chapters obviously, but that’s some of the background that we have under our belts, if you like.

Blank books. This is a blank slide. I have a couple of slides, nothing too fancy.

I remember reading a story, a piece in the New Yorker, a long time ago. It was a piece back when celphones had just started to appear in everybody’s hands. It was about a woman or a man, I can’t remember, and she’s hung up on by her boss or her partner or something, and you hear this delicious, rich multi-part click and then you hear a dial tone. The author was making the point, oh, look at these Hollywood sound editors, how behind the times they are, or how behind the times they think their audiences are, because we know, we New Yorker readers know, that celphone circuits don’t have dial tones. And yet, there it was.

Dial tones seems to be dying out the more we use cell phones, and yet it’s interesting to think where they come from in the first place. The author of this goes on to describe that dial tones were invented or became sort of ubiquitous only really when automated switching technology was applied to telephone circuits in the 50s or 60s. The dial tone was in a way, a replacement, if you like, for the operator. It used to be that you picked up a phone and a voice said, “Number please.” The dial tone was a way to say, “Okay, you can go ahead and dial your call,” without saying you can go ahead and dial your call.

So, why am I telling you this? It was that New Yorker piece that made me think about blanks. The dial tone is a blank. It’s an empty sound or it’s the sound of empty, into which you launch your call, your voice. Not quite signal, not quite noise, the dial tone represents an open channel. But more than that, I hope you’ll agree, that the dial tone also represents an absent telephone operator. It effaces labor. It disavows gendered labor as it alters your experience of communicating by telephone, helping you to forget – and you always do forget – that communicating with a friend on a telephone is always also, also always, communicating with your non-friend, the telephone company.

There’s a lot there, in blanks. Blanks are full of missing things, you might say. And it was after reading about the dial tone that I got so interested in pursuing blanks, and thought, hey, you better get back to a field of media history where you know something instead of talking about telephones, and that’s 19th century printing and books. So, I found this list of blank books– let me put it up there – in an 1894 dictionary of printing and bookmaking. I’m not going to read it, which is why I put it up there. But a few thoughts just as you look it over. It’s a list that points variously to the work place, market place, school and home, while it belies the assumption, one rampant in popular discourse today, that books are for reading. Books are for lots of things. Books like these were for writing, for filling in, or filling up.

Fillability, in some cases, seems to suggest a moral economy: mind you diary, mind your fern and moss album. But in many others, it suggests a cash economy with which North Americans in the 19th century had grown so familiar. Filling up evidently helped to locate goods, to map transactions, and transfer value, while it also helped individuals to locate themselves and others within or against the site’s practices and institutions that helped them to structure daily life. So, think of roll books, or workman’s time books, little instruments of power, if you like, locating as they do the schooled and the laboring. While hotel registers, rent receipts and visiting books point toward the varied mobility of subjects that stay over, reside or stop by. Letter copying books helped businessmen keep copies of what they also sent away. This was long before Xerox. While cotton weight and log tally books offer space to record one moment and always again the same moment in the life cycle of a bulk commodity. Some things are obscure. I have no idea what a “flap memorandum” is, or a “two-thirds book.”

The general picture, though, is one of motion, a confusion of mobilities really whereby goods, value and people circulate. They move through space and across borders from and to, they get caught and kept, they pause and pass, moving faster or slower. They also move in time because recorded in increments, and thus amid intervals.