The post Bums in Seats: Queer Media Database of Canada/Québec appeared first on &.

]]>The lights dim for the second of two screenings titled Matraques, a special event curated and organized by the Queer Media Database of Canada/Québec in collaboration with the queer film festival Image+Nation. The two-part screening is composed of twenty-one vignettes, each a short film or extract about the history of literal and metaphorical policing of queers in Canada. As the screenings end and the Q&A session starts, two things become evident. One: many people in the room know each other and others are being readily introduced, which makes knowledge of Canada’s queer history emerge out of the realm of shared collective memory, intensifying the already deeply communal nature of the event. Secondly, the bodies in the seats range from undergrads to seasoned film enthusiasts. Witnesses connect and respond to the programming on a visceral level, which for the younger people in the crowd enhances the immediacy of this history as represented in films that otherwise might have come across as demagogical or didactic. Judging by how no one feels like leaving Concordia University’s Cinema de Sève long after the films have finished, the screening is a resounding success.

A couple of days before the screening, I met up with Dr. Thomas Waugh and Jordan Arseneault. Prof. Waugh is Research Chair in Sexual Representation and Documentary Film at Concordia University’s Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema and president of the Queer Media Database Canada-Québec. Waugh’s books include the anthologies The Perils of Pedagogy: The Works of John Greyson (with Brenda Longfellow and Scott MacKenzie, 2013); the collections The Fruit Machine: Twenty Years of Writings on Queer Cinema (2000) and The Right to Play Oneself: Looking back on Documentary Film (2011); the monographs Hard to Imagine: Gay Male Eroticism in Photography and Film from their Beginnings to Stonewall (1996), The Romance of Transgression in Canada: Sexualities, Nations, Moving Images (2006), Montreal Main (2010). He is also co-editor of the Queer Film Classics book series. Arseneault is the coordinator of the Queer Media Database Canada-Québec, as well as a drag performer, social artist, writer, meeting facilitator, translator and former editor of 2Bmag, Québec’s only English LGBTTQ monthly magazine.

According to the website, the purpose of the Queer Media Database of Canada/Québec is to “is to maintain a dynamic and interactive online catalogue of LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) Canadian film, video and digital works, their makers, and related institutions.

How did the project come to be?

TW: There is a historic basis for the Media Queer Database. 20 years ago, when I started developing an encyclopedic project on Canadian queer moving image media, I saw and documented everything I could, thousands of short and long works. This documentation ended up in print form in my 2006 book The Romance of Transgression in Canada as an appendix to the main critical and analytic body of work. There are about 350 institutions and individuals embedded in the individual works that were catalogued and described. That print database festered and within five or six years we decided to bring it to life as a kind of living digital archive, using a Wiki model that would be maintained over time. My job is to supervise Jordan and other people working with the project, as well as guide the advisory board and push the project along. I try to empty my brain of data.

What do you mean by “Wiki model?” Does taking the online encyclopedia as a model imply a collaborative, open-source aspect for the archive?

JA: Copyright-wise, we decided to make it creative commons, which is different than a lot of academic material. This is a part of our mandate. There is also a submission form on the website. In other words, people can’t live-edit like they do on Wikipedia, but we do regular updates based on the submissions people give us. As the coordinator of the project, I periodically take the submissions that people have made, look at who we need to biographize, and then enter their filmographies, translate them, and so on.

Is there a lack of attention paid to Canadian queer cinema that this project is trying to address?

TW: Absolutely. Canadian work, especially in French, tends to become invisible in the global market. This is why we are committed to maintaining access to and visibility of these works. For this reason, the second phase of the project, once the website was up and running and our funds secured, became about programming. The Sunday event, Matraques, will be our fifth program of short and long films screened in the festival context in Canada. We are going international in 2016, with programs in India, France and Italy.

How is the project funded?

TW: We get funding from Concordia University, Canada Council, Heritage Canada and SSHRC. We also have partnerships with organizations across Canada who contribute moral support, facilities and some money, mainly in the form of accommodations and venues.

How has applying to these institutions and being helped by them verbalized the project?

TW: That is a very clever, Canadian question. Canadian culture and education are very much shaped by grant applications and criteria that everyone is scrambling to meet.

JA: We have been extraordinarily blessed with understanding on the part of these juries. People seem to get it. We applied for project funding that emphasized the national scope, research creation, public access to archival works… These are some of the trends we’ve tapped into. On the other hand, we haven’t been successful with one provincial funder who couldn’t conceive why we weren’t also streaming films. For them, a website hosting descriptions of artists and films did not really mean that much. Having said that, and having done the grant writing on the project since 2013, I find that there has been a very nice wave of understanding about the inherent value of having open-source material available on historic works. The AIDS Activist History Project, which is run by Alexis Stockwell at Carlton University and which collects oral history, interviews and names of activists and artists, has been similarly successful in that people understand how valuable primary source materials are.

TW: Streaming the films would also be great, but we can’t deal with the legality and materiality of rights ownership. Not only is it counter to our philosophy of copyleft and access, but it would also be a full-time industrial activity to maintain rights for 3,000 works. In fact, we want to support the distributors, exhibitors and rights owners who are doing their best to provide access to these works.

What are the project’s other institutional ties across Concordia? Prof. Waugh, you are a FIlm Studies professor at Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema, which also runs the Moving Image Resource Center here at Concordia.

TW: We are friends with them all. My primary unit is obviously the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema, that’s our nerve center in a way. However, it might be bodies that matter rather than institutions. This would not be happening if it wasn’t for individual people’s passions and obsessions.

We are sitting in Concordia’s Fine Arts PhD Study Space here in the Fabourg Building in downtown Montreal, where the office for the project is located. How does one go about acquiring a space like this? How does it help you achieve your goals?

JA: We had to do an application to the Faculty of Fine Arts, which includes conversations about outcomes, partner grants and byproducts, including how many student employees there are. There is a strong pedagogical component to the project, the training and mentoring of undergraduate and graduate students involved in the project either as interns or employees. That was a requirement for obtaining the space. In that sense, the project is part of the larger Fine Arts pedagogical operation. This space is sort of weird, with all the VHS cassettes and lots of cardboard boxes. There is some technology here, but we don’t really use that stuff (laughs).

JA: When I need to transfer what we’ve received from a filmmaker on beta to MiniDV to DVD, I have to go to one of our partner organizations. At best, we could hobble together a VHS-to-DVD [converter]. In other words, there could be more technical equipment here, but we are happy to have obtained this space as a place for the project to legally have an address. In a way, the materiality of this space reflects the obsolescence of a lot of material and technology we deal with: from festival catalogues to films on formats ranging from tape to DVD.

Within the next two years, what began as a distant pipe dream for many of the organizations we work with, making the films legally streamable online, will finally be a reality. This is maybe forty percent of the materials we are talking and writing about.

TW: We will host direct links to these works. We will remain necessary because none of the distributors are queer per se. We need to claim kinship with all these objects and people; otherwise, they remain unidentified. The distributors, out of politics of impartiality, do not play the game of naming that is essential for us. The presumption of community and kinship through naming is at the core of the project.

Moreover, I like the concept of materiality, as it segues into corporeality, and the audience’s bums in seats. They are the ultimate matter of this project to me, so it is very exciting to meet them all across the country and see them discovering these works.

The knowledge that emerges out of the database is embodied in the screening events that seem central to the project. Could you tell me more about these events?

JA: We will have organized nine such events across Canada by the end of the inaugural year. In Toronto, for example, we were in the Buddies in Bad Times community theatre in the Village, where, even though we presented with the Inside Out film festival, we screened during Pride rather than compete for attention in the festival context. The event was sponsored by the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives, and it was in dialogue with so many other events. In Vancouver, on the other hand, we were in the very chic Vancity Theatre and that was a more traditional cinema experience, with all the trappings of a film festival.

How do you envision these events? What kind of audience engagement are you trying to create, and what kind of “look and feel” do you think is the most conducive to the project?

JA: We do two different things. In Winnipeg, we were showing a film called Prison for Women by Janis Cole and Holly Dale, as well as Claude Jutra’s À tout prendre, a very crypto-gay film. However, I did a salon with local filmmakers, curators and their local distributer called Videopool the day before in order to get input about what we are missing in the catalogue. Before coming to this project, the screenings I’ve attended and organized were about hanging a sheet and acquiring enough folding chairs in order to watch a film that someone physically brought from the Berlin festival, for example. Film festivals are important for the legitimization of queer cinema, and so is the sense of community. That is why I love that sort of artisanal, communal, “pink popcorn” practice of spectatorship where people don’t mind if they don’t have the perfect line of sight. So in Winnipeg we got to do both a venue screening and a salon. We are doing another salon this coming January at Videofag, a queer space in Toronto where we will again be talking about what is missing from the archive and what our next foray of research should be.

What are the requirements for being added to the database?

JA: To be included, the work needs to have been shown twice publicly. Otherwise, the profusion of eligible works would be astronomical. We are still considering self-published work. For example, with web-based work, if it has been seen 1,300 times, that might count as a public showing. Because, let’s be clear, in the Canadian art realm, a majorly distributed work might have been shown fourteen times. It’s all still very indie.

What links everything from the latest Xavier Dolan film to a lesbian stop-motion animation about bunnies is the political significance of self-describing as queer and ascribing queerness to an art object. I wonder when that might be made obsolete. However, a part of me thinks that structural homophobia and misogyny will continue be present to such a degree that an explicit queer lens on the moving image will always be useful.

The post Bums in Seats: Queer Media Database of Canada/Québec appeared first on &.

]]>The post Performance, video formats, and digital publication in a Latin American context appeared first on &.

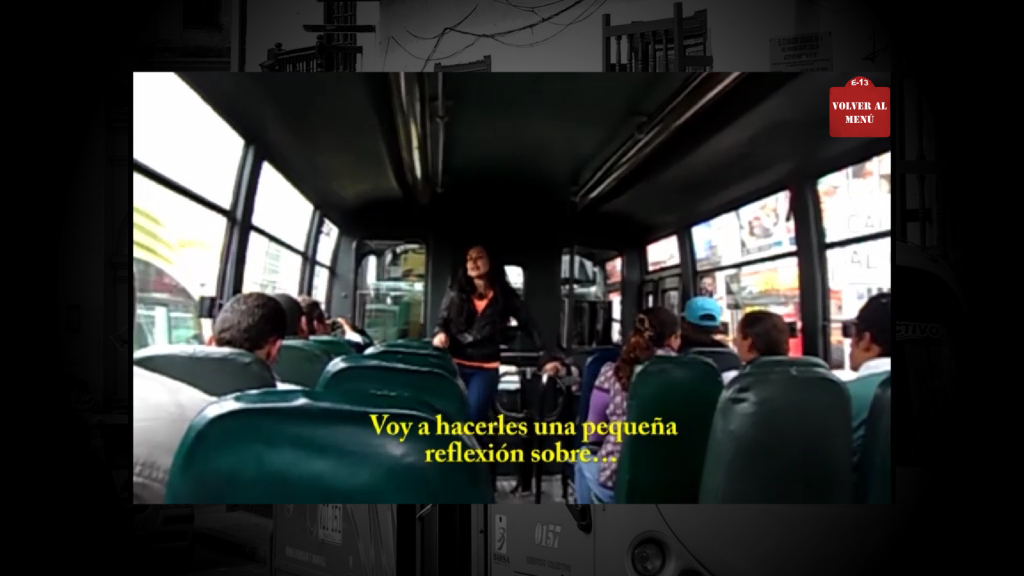

]]>Flaubert: 20 rutas consists of a series of performances made by Alejandra Jiménez in Colombia, where she delivered speeches based on texts by Gustave Flaubert to random users of the Bogotan public transport system. It is an intervention in the sense that it gets to an audience without it knowing or even wanting to experience such performance, rather than the audience consciously attending an artistic event. Also, if only haphazardly, it records the reactions of the public—sometimes they clapped at the end of the speech, sometimes they would remain silent, one lady would give her some flyers and information about God. Jiménez’s reflections on her performative interventions in her MFA dissertation (also called Flaubert: 20 rutas) seek to question the implications of transit and mobility in Colombia’s capital, as well as the replacement of old buses and busetas (small buses) by more modern models, the ways in which drivers used to appropriate their units and the advent of non-place-like environments in the new buses—cold, gray, almost antiseptic (Augé 2000; Jiménez 2013).

So Flaubert: 20 rutas is actually two works or, as I usually call them in this probe, two artistic products: the first one is a series of performances recorded in low-fi video—which is not just a byproduct of the performances but, as we will see, will take them to another sort of materiality. The second one is the research-creation dissertation defended by Jiménez at Universidad Nacional de Colombia (UNC). Given that the latter was already made public by the UNC web portal, the interest in the “publication” of Flaubert: 20 rutas was focused in the videos, since it recorded the reactions of the audiences randomly “formed” by Jiménez’s interventions on Bogotá’s buses and busetas, and therefore constituted a sort of “invitation to reflection” without recurring to academic rhetoric.

The videos, merged in F4V format, were gathered and displayed in a custom-made Adobe Flash Player application interface, made under Jiménez’s commission. Given that the only non-textual traces of the performance available for “publication” were the F4V files, the interface gave them a “database aspect”. All of the 20 performances are listed together in a 5 x 4 slot interface. Each slot is randomly numerated and identified with a distinctive title or topic: “Alcohol,” “History,” “Artists,” “Turning 30,” and so on. Recording the performances makes the project ambiguous in terms of function and materiality. As in the case of PDF, which reproduces paper in a digital environment (Gitelman 2011, 115), F4V is a digital file that mediates a video recording device, which in this case mediates in turn a time-bound artistic performance. It is the recording of the recording of the performance. But whereas a rose stops looking like a rose after several photocopies, in the videos the loss is both visual and aural, since not all the background details are clear or audible.

Before discussing video file formats as cultural artifacts in Latin America it would be good to give an overview of their proliferation and the process of standardization set forth by the ISO base media file format. Just as in the case of MP3 (Sterne 2006, 826), video files are called container or wrapper file formats, a sort of metafile which may be capable of storing multimedia data along with metadata for identification, classification, and reproduction purposes. Some container formats can be reproduced across different platforms. When I started downloading videos to play them on a computer, the most common file format for PCs was Microsoft’s AVI (Audio Video Interleaved), whereas Apple used QTFF (Quick Time File Format). Macromedia’s FLV (Flash Video) first appeared some years after AVI, and the interesting thing about FLV is that it supports streaming, making it easy to share, play and store in online digital environments, while it has a relatively small size, perfect for low-bandwidth internet technology. It became widely used by video streaming websites like YouTube and Reuters, but even before that Flash Player—Macromedia’s also small viewer application—was already popular after being integrated as a free plugin to the then famous Netscape internet browser. When Adobe bought Macromedia, in 2005, Flash Player was the most used multimedia player worldwide, either as an installed application or as a browser plugin, surpassing Quicktime, Java, RealPlayer, and Microsoft Media.

Despite FLV’s hype, when the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) came up with its base media file format, Quicktime’s QTFF was chosen as the base for standardization, probably because its potential components (audio, video, text for captioning, and metadata) were slotted in different “sub-containers”, which allows for edition and revision of specific parts without having to re-write all the information every time something is modified. From that moment, the authors of FLV have strongly encouraged users to switch to new container formats aligned with the ISO base media file format standards, such as MP4 for audio and F4V for multimedia.

Following the generalized call for standardization, the multimedia files for Flaubert: 20 rutas are encoded in F4V format. However, its quality makes it difficult to be uploaded to high-definition video websites supporting F4V, such as Vimeo, and it is more akin to low-fi environments like a great part of YouTube’s content. Although these videos are the registration of the core material for her research-creation project, the only published product so far has been the thesis dissertation. The videos allow for the ephemerality of the performance to be recontextualized in a digital environment, “micromaterialized” as proposed for the MP3 (Sterne 2006, 831-832) and therefore given a physical existence, however minute and encrypted it is. As in the initial functions given to gramophones (“storing”, so to say, the voices of people before they die), in Flaubert: 20 rutas the recording and digitizing of the performances made by Jiménez in the Bogotan public transportation system is a prime example of how to promote critical thinking out of creative events, while at the same time trying to overcome the temporal restrictions embedded in artistic practices such as music, sound art, and performance.

This probe will now raise some questions about the “publication” of the videos and its accompanying Flash Wave interface in a Latin American context. By “publication” I mean the public release of cultural artifacts through a mediation system, such as a publishing house. The work of mediation agents, such as editors and curators, has been widely analyzed by authors like Pierre Bourdieu as being fundamental for the acknowledgement of value and importance of cultural objects within capitalistic societies. Bourdieu asks who “authorizes the author” (2010, 156) in order to address how mediation agents (known in media studies as “gatekeepers”, see Shuker 2005, 117) deny the economic value of the cultural objects they promote and in so doing they “bet” for their potential symbolic value for a determined audience in a given artistic field. Without such “bets”, external and peripheral to their creative work, artists are arguably less visible in the artistic fields (Bourdieu, 2010).

Now, this is one way of seeing it. Clearly, publishing houses and galleries are nothing without artistic products. It is the commodity they commercialize. But the articulation of independent publishing collectives has the capacity to disrupt these hierarchical types of mediation. In the case of Flaubert: 20 rutas, the initial interface for the videos (see image below) was made by a Colombian programmer, whereas some arrangements have to be done by the programmer who will upload and maintain the site (designated by the publishing collective). Extra menus will be added in each “route” to increase the navigability experience and include complementary material—either transcriptions, critical reflections, or other related creative texts. A “shuffle” or random playing function, conceived by the first programmer but not given a visual interface, will be finally installed.

As I have suggested, one of the most interesting aspects these videos show is the difficulty to realize a performative intervention such as the one proposed by Jiménez. Randomness, which is at the very core of the creative process through the choosing of a determinate bus/audience, is reproduced or enacted several times throughout the project (the non-sequential numbering of the clusters, the “shuffle” function, and so on). In that sense, the idea of distributing Flaubert: 20 rutas for an ideally greater audience through the creation of a website interface seems to be in contradiction with the ephemerality that permeates the idea of this performance—and of performativity in general.

My concerns about the publication of this project in a Latin American context have to do mainly with functionality and accessibility. In Mexico, Colombia, and presumably in the rest of Latin America it is not common to have Flash Player installed as an application, but rather as an internet browser’s plugin. This means, on the one hand, that FLV is generally used only when accessed through streaming via YouTube or similar websites, and on the other that platform-specific formats like AVI are preferred when storing videos in a hard drive. Jiménez had the initial project of supplementing a CD with the digitized version of the videos with a FlashWave interface, which nevertheless restricted its playability to PC and impeded to play it as a DVD or VideoCD format. To understand why discussing format presentation is so important in a Latin American context, it is important to note that neither video disc players nor personal computers are commodities shared by all of the Latin American populations.

How different is the gatekeeper’s work from that of an artist uploading her/his videos on YouTube and somehow building a visualization interface for them, perhaps using predetermined template websites like Wix? The bourgeois bohemian sacralization of the artist as dedicated solely to the creative process, without being involved in the “dirty job” of getting an audience for it (Bourdieu 2010, 158), is highly responsible for the importance of mediation agents in the artistic fields. But rather than seeing mediation systems as opportunistic niches for the commodification of artistic objects, independent publishing collectives propose collaboration as a means to de-articulate the power hierarchies inherent in the work of mediation (here I’m using “work” in the same way Stuart Halls uses it in The work of interpretation, that is, as an effect exercised and set into action by mediation–the work mediation that “makes” upon its components). In that sense, most of the designing part was already done when it got to the hands of the independent publishing collective. The work of the next designer is for adaptability to the internet and “maintenance”, so to say. As they say in the editorial profession, “Everything is perfectible.” This does not mean the collective had inverted (either in economical or symbolic ways) so much as it could have if the author had not commissioned the creation of the digital interface beforehand. But it is exactly this focus on the mechanism of collaboration that can rather potentially offer a wider audience for a work that was buried under academic and temporal barriers. Of course, that does not prevent the publishing collective from adding its logo on the displaying menu, as there is in the end a collective “inversion” in the artistic product. Are the underlying structures of mediation questioned through this type of collaborative project? I do not totally think so, but I consider that it poses a working methodology open to the possibility of such questionings. What are publishing houses, then? Hubs full of nodes or links. Networks connecting to other networks connecting to other networks.

However, it is important to remember that in Latin America (and also in any other place touched by globalization), access to mediation systems is transversally restricted in terms of class/income, race, and gender. Any decision to use a technological device to transmit artistic media is therefore biased from its very conception. The practical objective becomes more fundamental than the ethical one: the technology with the biggest audience potential wins, and that is of course internet. Discs are in the process of becoming fully obsolete, just as 8-track cartridges, cassettes, and laser discs. But internet does not assure a durability of the database. The underside of internet is its potential for ephemerality. The hosting site can expire and not be renewed, and the database would be lost, if it is not lucky enough to be recorded by a database like the Internet Archive. So the “triumph over ephemerality” is probably delusional, while the supposed release of an artistic object to a wide audience is biased in transversally oriented levels.

References

Augé, M. (2000). Los no lugares. Una antropología de la sobremodernidad. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Bourdieu, P. (2010). El sentido social del gusto. Elementos para una sociología de la cultura. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI Editores.

Gitelman, L. (2014). “Near print and beyond paper: knowing by *.PDF.” Paper Knowledge: Toward A Media History of Documents. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 111-135.

Jiménez, A. (2013). Flaubert: 20 rutas. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia. MFA Thesis.

Shuker, R. (2005). Popular Music. The Key Concepts. London/New York: Routledge.

Sterne, J. (2006). “The mp3 as cultural artifact.” New Media & Society, 8 (5), 825-842.

The post Performance, video formats, and digital publication in a Latin American context appeared first on &.

]]>The post Dracula as Epistolary Database – Alanna, Jess and Hilary appeared first on &.

]]>For our Boot Camp, we worked together with programmers to create a database of the epistolary texts present in Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Alanna on her conception of the Dracula database project:

This project was a bit like diving into the deep end of a pool, never having seen water before. This is my first foray into the digital humanities, and it raised a lot of interesting questions over the course of the project. I considered whether using a digital tool for a Victorian project necessarily made it part-digital humanities. Does using digital tools make a person a digital humanist? Is a child using paints and brushes less a painter than Van Gogh?

Methodology

I decided to approach the project using a rough approximation of the scientific method. Just thinking about using a digital component changed my methodology—I was no longer only wearing my Victorian literature hat, I was heading into unknown territory and needed a helmet. For this reason, and also the sneaking suspicion that I had no idea how much I didn’t know, it seemed smart to document the journey as a sequence of hypotheses, predictions, experiments, and conclusions.

The Question

To build a digital tool for literary criticism is an excellent thing to do if it can contribute meaningfully to one’s research. In other words, does the tool have a function? It took some time to come up with the questions I wanted the tool to help me answer. I also reflected on why I wanted it – the digital humanities are a fashionable field, and it is easy to be drawn to them because there are lots of beautiful and interesting innovations, but ultimately, to build a database that does not serve a specific purpose is to build a toy, not a tool.

This project emerged from a question that came to me during the research for my MRP, Dracula’s Private Collection. What might happen when an epistolary novel, in this case Dracula, is restructured or reorganized in different ways? To find out, we built a database that would sort the items in the text by date, author, and genre, to see how the narrative might change. How might the text change in meaning if one were to read only the diary entries or letters? Does the text change in any significant way if it is reorganized to be chronological, or if we only read the men’s writing?

Beyond that, there is also a larger question concerning the archival nature of the novel. The novel is a collection of letters, diary entries, journals, newspaper clippings, and various other items that Mina Harker compiles into the archive and is ultimately the weapon they use to defeat Dracula. Dracula himself is something of an archive as well, because he is a masterful collector of languages, victims, and blood. Mina’s modern archive (modern because it is type-written by a woman) is used to slay this ancient, occult one, and so questions of archival violence begin to arise. Derrida’s concept from Archive Fever is useful here because authority is key.

Hypothesis: By creating a tool that can change the internal structure of Dracula, we will in turn create shifts in meaning that will yield new insights into the text.

Prediction: That this database will not only enable deeper study of the text, but also open up new ways of examining its structure and the metafictional constructs that make up the novel.

Experiment: Create a database, and use it to perform analyses of various sets of data.

Hilary and Jess on their experience working with the database:

In her probe for this week, Hilary wrote about the specific materiality of objects in the archive or “database” of a library, museum, or one’s personal collection—the material details that set them apart from one another. Just like any epistolary novel, Dracula’s objects of correspondence are catalogued within the pages of the book, made alike via their appearance on the page (the same font and spacing, etc.), but we, the reader, know that they are not alike in spirit. A letter from Mina or a telegram from Harker will feel like very different entities in our mind’s eye, as we read the story, because we extrapolate from what Stoker gives us into the signification of a letter, or a telegram, in all its ephemeral materiality. Yet the words of these documents also produce in us an affective response that sets them apart from one another. A telegram connotes urgency and is less intimate than a hand written letter, onto which we may imagine wax spilling and congealing or fingers smudging. Is consideration of such materialities (or lack thereof) considered distant or close reading?

To put this in conversation with the Manovich article, we can ask ourselves whether we are really de-materializing Dracula. Arguably, we are materializing it. To put it even more generally, we could question what our role is here, versus that of the programmers. (Especially given that the gender divide between us and them only served to further emphasize the gap in our knowledge). Here, for your (sadly?) comedic viewing pleasure, a photo that illustrates the chasm between us:

Are we interpreters of this data working with an entirely different paradigm-syntagm relationship? Haven’t we experienced a bit of an inability to communicate between disciplines because of this difference?

With these distinctions in mind, we approached the Dracula database project eagerly, hoping to learn something about code and, even better, to force ourselves to be interested in such an undertaking. While we did find the process fascinating, it was less because we became genius code masters, and more due to our interests in the mistranslations between us, as literature students, and the programmers. At one point, the three of us were talking about the “violence” that this type of project does to a work of literature like Dracula. The fact that these intimate epistolary exchanges between Stoker’s characters be reduced to a series of “stringlines” does seem violent, in a sense. Richard, the programmer, took issue with this word “violence” that was being used to describe his pragmatic pulling apart of the text, a reaction that interrogated our academic impulse to use such loaded words. The act of configuring a work of literature into a database in particular, is violent in that all the signified values conveyed by the language to the reader are eradicated and made useless. You can’t search for a document in the Dracula database by their affective or signified qualities (ie. “letters tinged with jealousy”)—it is only possible to identify entries by the simple imagistic qualities of the words that are present. A date, for example, has the date-word, the month-word and the year-word. There is nothing special about “October” other than the fact that it has an O followed by a C and etc. Lev Manovich addresses this when he writes that new media objects appear “as a collection of items on which the user can perform various operations: view, navigate, search. The user experience of such computerized collections is therefore quite distinct from reading a narrative or watching a film or navigating an architectural site” and that the result of the database is a “collection not a story” (2, 3). Manovich writes that “computer programming encapsulates the world according to its own logic” and he distinguishes between two types of “software objects” which this world is reduced to: “data structures and algorithms” (6).

One of the first things Richard the programmer showed us was the file of Dracula that he had found on Project Gutenberg:

Questions of provenance, text form and text edition came up in discussion of which version of Dracula was being fed/scanned into the database. Should we question the authority of a project like Gutenberg on such matters, we wondered. Does it matter that we’re working with a digital text rather than manually scanning/transcribing a physical copy? Is there a different materiality at play? Even with the physical book there is already a sense of duplication—the narrative is a sum of textual copies; Dracula is also a creature seeking replication, and as immortal and theoretically vanquishable as a digital copy. Jess mused that she found it fascinating to think of this database project as just another vehicle for Dracula’s world contamination and pathology in that it gives new meaning and agency to his monstrous textuality, which we are in effect enacting. In a weird way, in decomposing the text through the archival process, the text itself is becoming more real—an uncontrollable thing that both necessitates human activity to bring the database to life, and yet in its potentially endless unfurling/mutation becomes increasingly inhuman as the text-objects are dissociated from narrative patterns.

In order to “read” the markup language attached to file, the programmers needed to try different reader programs such as Eclipse, Java, then Python, and finally settling on C sharp.

They used an addition to C Sharp called Re-sharper which improves the function of the program. Richard told us he would have to delete the table of contents from the file’s markup language as it was superfluous to the database project (this is one place we talked about “violence”). Richard briefly explained object-oriented languages to us—first you create classes, such as “file reader,” and then objects, which must have the same name as a class. Once you’ve created your attributes for said objects, you can examine the strings of the file (or the sequence of characters, such as a sentence) and look for patterns which may be useful to you. Then you must create conditions, using words like “while” and “else” that will allow you to act upon the objects. Because we wanted the database to separate the entries by name, date and medium, we needed to create conditions that would act upon the stringlines within the file and pluck out all Journal Entries, for example.

The Future of this Database

HTML v. XMLTEI

The text is HTML, which is ultimately a code for presentation, for visual reference. The consequence of coding for display, rather than coding for meaning, is that this HTML version is really only useful to Alanna. It does not contribute to the larger scholarship, and it does not allow for other scholars who wish to manipulate Dracula digitally to do so except in very narrow ways. It might be fun for undergraduates who are working on Dracula but for larger projects, its usefulness is limited. The way to correct this is to create a version using XMLTEI because that is a language that codes for meaning. It looks almost exactly like HTML, and if you know HTML you can learn TEI quite quickly, but the reason it is so much more useful is because you can code for anything. If you want to create a personography, you can create TEI PersName tags around each occurrence of a given character’s name: “One day, <persname> Alanna <persname> walked down the street.” This allows for navigation through the text in a way that follows one storyline, because now that name has been linked semantically to an entry in a personography. Anything can be coded: names, dates, characters, objects, particular words, even smudges and marks on the paper of a given manuscript.

There will inevitably be more coded values and meaning than what any given scholar might use. The value of this is that the tags are never taken out, and that means that even if one person decides that dates are not important, someone else who does can do so with relative ease.

The way to use XMLTEI is to first check if the text you want to work on is an XML document that is also TEI compliant, or if it is just HTML. This information will usually appear in the header. It is also necessary to learn XSLT, which is a way of navigating TEI. Software developers will laugh because these are “so 1993,” as one recently put it. However, TEI has evolved into something of a specific digital humanities language, and so what is obsolete in the software world is not in the digital humanities. It is the most used language before making the jump to something like MySequel (a database language), and Python or one of the other high-performance languages.

To use these tools on Dracula and on other Victorian gothic epistolary novels will take a significant amount of time and also probably money, as well as training in TEI and XSLT. For these reasons, it is not practical to undertake them now for the sake of upgrading the Dracula database, but it does open up various possibilities for a larger, more sustained project in the future.

This brings us to yet another line of query: Is deconstructing Dracula in this fashion helping us experience the phenomenological horror that is Dracula on another level? Are we seeing the text assuming a new autonomy? Accessing Dracula through such a database in a way means breaking away from reading habits such that we are confronted with the impersonality of all texts. There is a disturbing interaction here between human and nonhuman elements that the database-building process reveals.

How much does the human recede into the nonhuman or vice versa?

Are we not seeing our own scholarly desires being translated into code?

Are we not probing into language’s otherness and translating it?

Some of the words that the programmers used interested us, such as “ugly” to connote variance (for example letters on which the dates deviated from the standard format, “day, month, year”). Whereas for Richard, “violence” was a hard word to swallow, Hilary noted that for her, “ugly” felt the same. Perhaps “deviant” would be a more accurate term? But that too implies that there should be some sort of standard formatting for dates of handwritten letters—an assumption that further erases the individual, human (or, in this case, character), handwriter from the letter-writing process (and the materiality that we continue to cloyingly hearken back to). The names of the programming languages also interested us. One of them, called “Lisp,” uses brackets for comments and apparently isn’t known for running smoothly. The name amused us as the implication of speech impediment made clearer the distinction between the human user of these languages and the coded language itself—as well as the awkwardness that may ensue when the two attempt to grapple with one another.

Jess wondered whether there wasn’t a kind of terrifying repetition to this whole process— or a sense of never really moving forward, and how this might offer a different experience of textuality? Dracula is itself a terribly repetitive narrative. We wondered whether, by participating in this project we’re looking for something external to the text— not part of the text itself but peripheral to it that the mechanics of archiving would render visible?

Graham Harman’s article, “The Well-Wrought Broken Hammer: Object-Oriented Literary Criticism,” in which he addresses the autonomy of textual objects from their relations and New Criticism’s holistic conception of the text’s interior, can speak directly to our project. Harman questions which features of a text or work of literature are essential to its definitive objecthood:

We can add alternate spellings or even misspellings to scattered words earlier in the text, without changing the feeling of the climax. We can change punctuation slightly, and even change the exact words of a certain number of lines before [the text] begins to take on different overtones…the critic might try to show how each text resists internal holism by attempting various modifications of these texts and seeing what happens. Instead of just writing about Moby-Dick, why not try shortening it to various degrees in order to discover the point at which it ceases to sound like Moby-Dick? Why not imagine it lengthened even further, or told by a third-person narrator rather than by Ishmael, or involving a cruise in the opposite direction around the globe?…In contrast to the endless recent exhortations to “Contextualize, contextualize, contextualize!” all the preceding suggestions involve ways of decontextualizing works, whether through examining how they absorb and resist their conditions of production, or by showing that they are to some extent autonomous even from their own properties. Moby-Dick differs from its own exact length and its own modifiable plot details…there is a certain je ne sais quoi or substance able to survive certain modifications and not others. (Harman 201)

Similar questions can be asked of our project—which uses such an object-oriented database model: are we stripping away at all the inessential qualities of Dracula? Are we left with anything that is essentially Dracula? That makes it recognizably such? Having said earlier that we are expanding the text of Dracula or metastructuralizing it it’s weird to think we are in the same gesture stripping it down to its bare parts.

By now, it has probably become clear that our boot camp project raised many questions for us, but these are, in fact, the types of questions that only a project such as this would fully force us to ask. In the face of the inevitable “So what?” we could respond that we have attempted to take Bogost’s suggestion to heart—that to build something can help you better understand it (or, in our case, help you realize how little you understand it)—that a project which represents “practice as theory” (111) is a worthy one, regardless of the outcome.

Works Cited

Brazeau, Bryan. Personal interview. October 3 2014.

Harman, Graham. “The Well-Wrought Broken Hammer: Object-Oriented Literary Criticism.” New Literary History 43.2 (2012). Print.

The post Dracula as Epistolary Database – Alanna, Jess and Hilary appeared first on &.

]]>The post Database Dance Floor: Manovich and Leckey appeared first on &.

]]>The idea of a database would be somewhat terrifying, I imagine, for the things that are databased (or archived), if they had the capacity to feel terrified. To be swallowed up by the endless object-pool of the internet is to be flattened out into sameness and obscurity. Gone are the hierarchical or affective qualities that we attribute to our scuffed record sleeves, spattered recipes, tear-stained diary entries and creased love letters — online archival tools such as email, YouTube and Itunes have successfully erased the traces that make objects significant (or even worthy of archiving), yet have also redefined the archive in terms of efficiency and ease of use. Lev Manovich recognizes this shift, writing, “New media does not radically break with the past; rather, it distributes weight differently between the categories that hold culture together, foregrounding what was in the background, and vice versa” (13). Not only does the new media database change the way we think about individual components of the archive, it also affects our conception of the narrative that often accompanies these types of catalogues.

Although it is now nearly fifteen years old (the same age, in fact, as Manovich’s article), Turner prize-winner Mark Leckey’s 1999 film Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore is an interesting art object (or collection of objects) from which to examine the re-distribution of narrative “weight” which Manovich addresses. Fiorucci is composed of a selection of found video footage of Manchester’s underground nightlife and dance scene, from the northern soul movement of the late 1960’s to the football casual scene of the eighties and the rave culture of the late-eighties/early-nineties. Leckey avoids overtly chronological ordering, linking these moments together, rather, with themes of nostalgia, youth culture, performance and anonymity. The film is intentionally jarring in its repetition of images and sounds, and although it may seem ambiguous in its narrative direction, it does have at least one clear trajectory: the movement from the individual dancer as subject to his/her subsumption into the throbbing crowd of the many-bodied dance floor. Passage of time is also emphasized, on the surface of the screen itself, by the near-constant presence of a rolling digital time code common to many early-nineties video cameras. The ascending numbers convey a sense of urgency as time is clearly ticking by, while the numbers’ incongruity between unrelated snippets of film supports Fredric Jameson’s definition of postmodern temporality as “a series of pure and unrelated presents in time” (73). Manovich offers a similar approach to new media objects, which he explains, “do not tell stories” and in fact have no “beginning or end” nor any “development, thematically, formally, or otherwise which would organize their elements into a sequence” (1). Leckey juxtaposes an awareness of the temporal progression with sudden freeze-frames of dancers’ faces. During these uncanny moments of frozen time, the “present” can be seen to “suddenly engulf” Leckey’s dancer-subjects with “undescribable vividness, a materiality of perception properly overwhelming” (Jameson 73). In this way, the viewer of Leckey’s video is also “engulfed” by the feeling of a constant present, and the “vividness” that Jameson describes can also, presumably, serve as an apt description for the rave experience itself.

Manovich notes that if the internet world “appears to us as an endless and unstructured collection of images, texts, and other data records, it is only appropriate that we will be moved to model it as a database — but it is also appropriate that we would want to develop poetics, aesthetics, and ethics of this database” (Manovich 2). He writes that database and narrative are “natural enemies” (8), but Fiorucci seems to straddle the space between the two. In a recent interview about his 1999 work, Leckey explains that he was driven by the nostalgia he felt for his youth to recreate “his own past using other peoples’ footage” and “reassemble his memories” using a “collage”-like, non-narrative method (Vimeo). It is this swapping out of our own memories for other peoples’ that is made possible by the features of the database which Manovich describes. How odd, that something as particular as a personal memory could be approximated through others‘ records of like memories. What becomes clear is that the memory, as an object itself, is less unique than we think, but that even in its interchangeability is still capable of producing the kind of affective response that we usually attribute to those creases, spatters and tear stains that materiality offers. Leckey confirms this, saying “It’s quite a sad movie…Fiorucci is an elegy for a time that’s gone” (Vimeo). He goes on to explain that although the film was made before YouTube, “it came about because of technology, because of computers,” thus tying his work to the capabilities of new media databases (Vimeo).

If the concept behind Leckey’s film is complimented by Manovich’s analysis of databases, so too can the “narrative” that Fiorucci takes on be seen to mirror the trajectory Manovich tracks, from old media to new — from hierarchical, special ordering to flattened, non-ordering — in its portrayal of the growing faceless dance floor. Throughout the film, the music to which the club-goers dance is nondescript yet rhythm-heavy; Leckey overlays his footage, culled from various temporal and spatial realms, with one relentless soundtrack of droning bass. The film’s use of relentless disco rhythms gives way to a “disembodied…eroticism” that divests the subjects’ dancing bodies of individualism (Dyer 104). Scott Hutson calls the specific type of movement inspired by electronic dance music “dance as flow” and he notes that this type of dance “merges the act with the awareness of the act, producing self-forgetfulness, a loss of self-consciousness, transcendence of individuality, and fusion with the world” (Hutson 39). In some ways, when dancing to electronic music, the self no longer operates the body. Instead, the movement of the body becomes involuntary, controlled by music and rhythm alone.

Beatrice Aaronson notes that, over time, the dance floor has indeed erased individuality, writing that “techno and rave dance floors have indeed become a ritualistic space of rhythmic cohesion that enhances togetherness and transgresses all constructs of difference…there is no hierarchy” (231). Reynolds points to an individuation of a different sort in Leckey’s film when he emphasizes that the “materiality” Leckey locates in his dancing subjects is, importantly, “insistent but mute” and not quite human in its “limb-dislocating contortions, foetus-pale flesh,” and “maniacal smiles” (Reynolds). This is exactly the kind of monstrous, “fragmented” subject Jameson predicted in “Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.”

If, according to Jameson, the postmodern subject is no longer “alienated” but “fragmented,” perhaps our urge to synthesize with the crowd is evidence of our residual alienation, and in fact, it is the actual act of blending that fragments us. Jameson writes that, in postmodernity, the “liberation…of the centered subject may also mean, not merely a liberation from anxiety, but a liberation from every other kind of feeling as well, since there is no longer a self present to do the feeling” (64). He almost skews this lack of self as positive—he writes that feelings are now “free-floating and impersonal, and tend to be dominated by a peculiar kind of euphoria” (64). Jameson portrays the relief from personal relationships and emotions as “euphoric,” similar to the feeling of the dance floor, where dancers are divested of individuality.

…But we have come a long way from my original linking of Leckey’s film and Manovich’s thoughts on database and narrative. Manovich writes that the “open nature of the Web as medium” contributes to its “anti-narrative logic” and that “If new elements are being added over time, the result is a collection, not a story” (Manovich 4). I’m interested in how a collection can also be a story — or rather how we always read narrative into collections, despite the disparity of its parts, even before the yawning terror of the endless database. Somehow, a video art collage like Fiorucci can host and inspire intense nostalgia for Leckey’s (and countless others’) personal memories without particularity. Does the fact that the Internet-archive is home to countless swappable objects mean that our pursuits of identity-formation are rendered inconsequential? Though Leckey’s film doesn’t follow Mieke Bal’s definition of a “narrative,” it does portray a “series of connected events caused or experienced by actors” (Manovich 11). It’s just that these actors do not remain constant. In fact, it is essential that they change. It seems to be Leckey’s vision that these people are interchangeable — and that their very presence on the dance floor, lost in movement, subsumed into the throbbing crowd, makes it so.

Works Cited

Aaronson, Beatrice. “Dancing our way out of Class through Funk, Techno or Rave.” Peace Review 11.2 (1999): 231-36. Project Muse. Web. 19 Nov. 2012.

Dyer, Richard. “In Defence of Disco.” 1979. New Formations 58 (2006): 101-108. Print.

Hutson, Scott R. “The Rave: Spiritual Healing in Modern Western Subcultures.” Anthropological Quarterly 7.1 (2000): 35-49.Academic Search Premier. Web. 22 Nov. 2012.

Jameson, Fredric. “Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.” New Left Review 146 (1984): 53-92.

Leckey, Mark, dir. Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore. 1999. YouTube. Web. 19 Nov. 2012. <http://2012popmusictheory.aburke.ca/2012/11/19/fiorucci-made-me-hardcore/>.

Reynolds, Simon. “They Burn so Bright Whilst You Can Only Wonder Why: Watching Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore.”Reynolds Retro. Ed. Simon Reynolds. 14 June 2012. Web. 22 Nov. 2012. <http://reynoldsretro.blogspot.ca/2012_06_01_archive.html>.

The post Database Dance Floor: Manovich and Leckey appeared first on &.

]]>The post The IKEA Catalogue: From the “BookBook” to the Database appeared first on &.

]]>

This IKEA advertisement describes their catalogue (a book) in the terms we would normally use to describe a new form of technology (namely computers) while mimicking the tone and aesthetic of Apple advertisements. Forbes recently published a post linking this Ikea advertisement with a Norwegian sketch called “Introducing the Book” that was posted before the iPad first came out (Forbes). What we don’t realize is that the books that we carry around in our bags and stack in our lockers were once a new technology as well. The comparison of these two videos points to this oversight. I became very anxious while reading through Lev Manovich’s article Database as Symbolic Form. It made me think: what isn’t a database? My IKEA Catalogue, for instance, is just a printed form of their website where I can type in “napkins” and have every different colour and pattern of napkin they carry pop up, each with its own Swedish name that I can’t properly pronounce. The website is a database that stores information that is readily available to their customers: what stock is currently available in their online store, how much it costs, whether or not it is on sale, how big it is, what colours it comes in, how many napkins come in a pack, and even allows their customers to see if the product is in stock at their local IKEA. IKEA, like many other businesses, uses databases not only to manage their inventory, but also to store information about their customers, mailing lists, catalogue subscriptions, Family Card membership information, images from their customers’ 3D kitchen designs, as well as information from every single kiosk their customers use at the self-checkout at the end of their visit at a store or online. In fact, the database was an integral part of their marketing scheme when IKEA decided to become not only a kitchen retailer, but a kitchen expert. An article on Figaro Digital explains the necessity of the database in IKEA’s plan:

In providing their customers with a virtual way to design their home, IKEA is using what Manovich calls the “paradigm”, or the imagined realm, to imagine the actual realm or what he calls “syntagm” (Manovich 14). However, this isn’t the only way the postmodern experience is at play in the way that Ikea presents itself to the public.

Let’s consider the IKEA store itself. Shopping at IKEA is a narrativized experience, one that is similar to attending a museum exhibition, going to an amusement park, or going to see a theatre production. “A museum becomes a database of images representing its holdings, which can be accessed in different ways,” writes Manovich, “chronologically, by country, or by artist” (3). This is similar to the ways in which one can experience the IKEA store, however, the predominant shopping experience is as follows: You walk into the store, grab a bright yellow shopping bag or shopping cart, grab a white gridded paper and a little Ikea pencil to write down the product names and where they’re located in the warehouse, maybe even grab a paper IKEA measuring tape, and then you begin to follow the little yellow footsteps that are glued to the white linoleum floor. Next, you are guided through the staged living rooms, brought next into the room full of every different couch Ikea is carrying at the time, next to (I can’t remember exactly) the staged kitchens, next past the kiosks with computers and experts (Ikea employees) where you can design your own dream kitchen, next to the room with all of Ikea’s dishware and napkins, next to the staged bedrooms, next to the room with all of the beds and bed frames and bed sheets IKEA carries, and so on, until you reach the scented candle and picture frames room where you feel sad because your narrativized, guided Ikea experience is almost over, and soon after you reach the warehouse, where, in a very post-modern way, you must find whatever furniture you are going to buy all on your own, using the notes you made yourself on that little white piece of gridded paper with that tiny Ikea pencil they provided you with when you entered the store and began your prescribed route through their showroom. The warehouse, in having the customer find the various pieces of the furniture they are choosing to purchase themselves, is a very database-like experience. In the warehouse, the customer must construct the narrative of their experience for themselves, completely unlike the rest of the IKEA experience where the narrative is guided and planned for the customer. Unlike a regular department store or a museum as described by Manovich, it is very difficult to just go to IKEA to buy bed sheets because it is very difficult to get directly to the bedroom section without first going through the living room section and, let’s be honest, it is very difficult to avoid the colourful children’s section, as the little alleyways that let you skip ahead in your IKEA experience aren’t as well marked as the little footprints on the linoleum floor. The way that the showroom is designed makes flowing from one section to the next the easiest way to experience IKEA, and it is part of what makes shopping at Ikea so much fun.

The IKEA shopping experience mirrors what Manovich describes to be new media’s relationship with the terms paradigm and syntagm: it reverses it. “Database (the paradigm) is given material existence, while narrative (the syntagm) is de-materialized. Paradigm is privileged; syntagm is downplayed. Paradigm is real” (15), as you’re actually picking up the objects you’ll be bringing home with you in the warehouse, “syntagm is virtual” (15), the objects in the showroom remain on display even after you purchase their components that you picked up in the warehouse. The database is not only used by Ikea in a literal way when you subscribe to their catalogue or their Family Card, it is also used as a cultural form when you consider that from the moment you walk in, you are marking off the items that interest you in the store (just as you would click on them online and add them to your shopping cart), you are collecting the pieces to put together the furniture in the warehouse (the deconstructed furniture itself is an example of the postmodern industrial structure of IKEA), and when you go to pay for the furniture, you are now scanning each item yourself and loading it back into the cart or into the big blue IKEA bag you’ve purchased (just as you would type in your address and credit card information online). At IKEA, “the narrative is constructed by linking elements of this database [of IKEA’s inventory] in a particular order—designing a trajectory leading from one element to another” (Manovich 15).

The IKEA Catalogue, a printed book that seems to preserve traditional material culture, is in fact a cultural form constructed from a database of computer graphics (CGs). In fact, “60-75% of all of IKEA’s product images (images showing only a single product) are CG” (Parkin). Since 2010 IKEA has also been creating entire room images in CG because of how easy it is to substitute certain elements such as fridges, faucets, and cabinet hardware without having to reshoot the entire frame. CGs help IKEA save time, costs, and environmental pollution associated with shipping (Parkin). The fact that IKEA Catalogues themselves no longer exist without the help of a digitized system to design the format and to create the images inside of it, make the “bookbook” advertisement intensely ironic. In fact, if you flip your IKEA Catalogue over to the back cover, you’ll notice a margin that reads, “SCAN THIS PAGE REGULARLY TO GET MORE OFFERS FROM IKEA” (IKEA Catalogue). Now when you go through the IKEA Catalogue, you’ll notice white plus signs in orange circles at the top right hand corner of certain pages and a caption that reads, “Scan this page” (IKEA Catalogue). The IKEA Catalogue is now reliant on the technology of your tablet or smartphone—you must download the Ikea Catalogue application in order to fully appreciate your “bookbook”. Without the application, what you see is what you get. However, with the IKEA Catalogue app, you have access to special offers when you scan the back page and “extra content” (Ikea Catalogue 5) when you scan each marked page, including 360 degree views of the rooms featured in the catalogue and tips for styling a room with IKEA’s products. Their website advertises that the application is going to be able to do even more in the near future, including background stories about the products and the designers, “inspirational how-to films”, and “augmented reality, place furniture in your room” (IKEA website).

The IKEA Catalogue application makes your browsing experience almost completely virtual: you no longer have to imagine what the furniture in the catalogue would look like in your home, you can now hold up your iPhone as a lens and pretend that you have a new IKEA couch in your living room. The “bookbook” is no longer the cultural object, it is merely the façade of a cultural object that is a large database of videos, stories, 3D applications, digital images, and other materials that are inaccessible without technology. The irony of the bookbook commercial is almost heartbreaking once one considers the IKEA Catalogue application and now the commercial must be read as a piece of cultural criticism. A cultural form that is traditionally read as a chronological narrative (the book), or what Manovich calls a “hyper-narrative” (Manovich 10), now has a less overtly linear structure where one can choose to veer off and explore different aspects of what is printed on the page, in this sense, IKEA has found a way to “merge database and narrative into a new form” (27).

How has the database as a cultural form changed the way that we interact with old technology that is not digital itself? In particular, what has the database as cultural form done to traditional book culture? How has this cultural form changed the ways in which we interact with the real world? Is it possible to enjoy the IKEA Catalogue at all without experiencing the overwhelming feeling of FOMO (fear of missing out) if one doesn’t download the app? What contemporary cultural objects are not influenced by the database as a cultural form?

Works Cited:

“Case Study: IKEA: the Kitchen.” Figaro Digital. Web. September 29th, 2014.

IKEA Catalogue. USA, Inter IKEA Systems B.V., 2014. Print.

Manovich, Lev. “Database As Symbolic Form.” Database Aesthetics: Art in the Age of Information Overflow. Ed. Victoria Vesna. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007. 39-60.

“The IKEA Catalogue 2015.” Ikea.ca. Web. October 5th, 2014.

The post The IKEA Catalogue: From the “BookBook” to the Database appeared first on &.

]]>The post Show Facts, Hide Facts: Applying Latour to Database Structures appeared first on &.

]]>Probe, or Rogue Suicide-Bomber Probe Droid? (Is that a fact?)

In view of our reading of Latour’s rearticulation of the assumptions informing the concepts of “facts” and “values” into new terms that recognize the processual cyclicity of institutionalizing always-debatable uncertainties into useful certainties, and in view of Alice Munro’s having just been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, an article entitled “Denied Nobel Prize Yet Again, Margaret Atwood Plots Post-Apocalyptic Revenge” seems timely. The article appears on the website Newslo, which boasts (with apropos unabashedness with respect to facticity) the title of “The First Ever Hybrid New/Satire Platform!” The title captures accurately, however, the Newslo site’s hallmark article-viewing functionality: a toggle for “Show Facts” and “Hide Facts” foots every article. Activating the former button highlights the portion of the article that has been institutionalized to the realm of what we would previously have called facticity; re-negating these highlights (back to the article’s default appearance) returns smoothly and non-libelously the factual portions into formal homogeneity with the sensationalist satirical tabloid remainder. “Just Enough News,” runs the site’s motto, which is just as well an ironic motto for news in general nowadays: there’s too much news, and yet never enough “(f)actual” news in that news (and never enough fiction in our “fiction“). How can we better define that “just enough” (with pun on “just”)? We need what Latour proposes: a better “power to take into account” (Facebook account or otherwise): we need to evolve our filter-feeders.

Indeed, Newslo’s filtering system typifies the related problem of facticity in regard to digital public spheres that we discussed both yesterday in relation to a Quebec provincial voting commercial, which we argued exemplified the complex relations governing the way in which the mob rule of social media gets billed as democracy via that social media itself, as well as last month in relation to our discussion of print newspapers versus databased newspapers and the personalized newsfeed. “Filter bubbles,” Ted Talker Eli Pariser calls it, this Internet censorship phenomenon in which our bias towards our own politics of interest can actually work against our own interests – especially when, as Pariser relates, Facebook one day decides to run an algorithm (just for “you,” i.e. for you) that converts all your visible news into whatever your Good News happens to be. While the talk is scarcely worth skimming beyond what I am graciously filtering for you, Pariser does end up proposing that databases like Google adopt what amounts to an extension of the logic of Newslo’s system: namely, including among our “sort by” options checkboxes for things like “Relevant”, “Important”, “Uncomfortable”, “Challenging”, and “Other Points of View”. The metaphysics of presence points to an obvious problem with this system, or rather with the utopian version of it (a database will never represent what is truly Other to it – we, and even Google, simply cannot know how “Other Points of View” is itself being filtered; and is a comfortable way to find the “uncomfortable” possible?), but nevertheless the gesture seems valuable, and maybe even represents a crude attempt at doing for the database what John Law proposes scholars do for research in general: making explicit to our readers the always-messy contingency of that research. Perhaps databases should have a “messy” filter (kind of like the trope of the button which you’re told never to press because no one knows what it does), which when you press it simply puts everything through a glitch-randomizer and fucks everything up.

It is such mess, though, that Latour likewise encourages as the one of two requirements of his proposed initial phase for institutionalization (what in the old language we would call fact-making), the phase of taking into account all of the entities that we have at our disposal to debate for institutionalization candidacy: namely, the requirement of perplexity, a “provocation (in the etymological sense of ‘production of voices’)” in which “the number of candidate entities must not be arbitrarily reduced in the interests of facility or convenience” (110). Its corollary is the requirement of relevance – considering the relevance of the various stakeholding voices to perplex what is being, by debate, perplexed. This latter somewhat relates to Pariser’s proposed (re)search filter category, but more to that mark is the requirement of hierarchization in Latour’s second of the two institutionalization phases, arranging in rank order. For, Pariser’s category of “Relevance” (and rather than simply pertaining to the already-familiar category of “sort by relevance” vis-a-vis search terms) comes in critical response to Mark Zuckerburg’s cited remark that “[a] squirrel dying in front of your house may be more relevant to your interests right now than people dying in Africa.” Pariser’s point is that, if newsfeeds or other search results are ever to even approach something more like the impossible ideal of information democracy to which popular media discourse so often articulates them, then the squirrel pictures that come up in our newsfeeds should perhaps not be placed at the same level of relevance as humanitarian crises in what Latour calls society’s “hierarchy of values” (107) (which also, notably, functions by a “[r]equirement of publicity” [111, emphasis added]).

The comparison to be made, then, is between the (in the old terms) “fact-evaluation” process that Latour proposes for constitutional democratic government, and the way in which information is similarly filtered to and filterable by the public of such democracies within their digital news and (re)search platforms. Latour’s proposed process begins with perplexity and relevance – in other words, the collection of search results (the terms – relevance – and their results – initially, perplexity) that then, in the second part of the process, the move toward actual instutionalization (“closure”), must get hierarchized accordingly in terms of their hierarchical ethical valuation. In sum, it would seem that, in extension to Newslo’s and Pariser’s unique filtration systems, and indeed as a corollary component to the type of public network resultant of precisely the kind of (public sector) debate apparatus that Latour proposes, our new digital filtration systems should involve not just parameters like “Show Facts” and “Relevant” but precisely such a process as Latour’s, with its unique re-articulation of “facts” and “values” into less contradictory categories. Then a system such as Newslo’s could only constitute absurdity insofar as “facts” would no longer be a category for filtration. But more importantly, because the relative contingencies of what we used to call “facts” (and get mixed up with “values”), and the (traces of the) process by which they became such, might be explicitly built into all our articles and newsfeeds and other search databases. That is, the equivalent of “Show facts”, for example, would show (by a kind of markup, perhaps) what had been successfully put through Latour’s process of institutionalization.

Otherwise, Margaret Atwood might still be in the running, according to her own personalized fantasy newsfeed. For the division between “facts” and “values” (where the latter equals the explicitly skewed satire in Newslo’s articles) is never so clear as Newslo makes it. Hence the need and use for Latour’s proposed new articulations.

Works Cited

Latour, Bruno. “A New Separation of Powers.” Politics of Nature: How to bring the Sciences into Democracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004. 91-127. Print

Law, John. “Making a Mess with Method.” Lancaster: The Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University, 2003.

http://www.comp.lancs.ac.uk/sociology/papers/Law-Making-a-Mess-with-Method.pdf

The post Show Facts, Hide Facts: Applying Latour to Database Structures appeared first on &.

]]>