The post Google Translate: Glitch Art and Deformance Methods appeared first on &.

]]>Probe * Nov 21st

“Dominate the dream of freedom due to the translation, materialized, reduce A normative struggle, new analysis focuses on what we call the transfiguration seems Emerging. This could significantly change the way through the public decision-making Close to the regime of recognition. No one claimed that schools have been decisively This concept covers the terrain. Even if we see the development of scholars, it is doubtful analysis protocols circulation and transfiguration understanding Replace the meaning and translation tools to understand they are doing Or so. However, the entire work, could not be more different in style, tone, Content and discipline, we see the development of new technologies catch Mapping function, not meaning as foreground figure Public culture technology Public Forms Coordination and figurating machine, the main component is not Situated in the play signifier and signified but functional indexicality Imitation (iconicity)…”

- Gaonkar & Povinelli Technologies of Public Forms: Circulation, Transfiguration, Recognition. Translated with Google Translate, 394[i]

Just when I was about to enter high school, my home state of Minnesota began one of the state’s first Chinese language programs. I jumped at the chance. While French and Spanish were great options, they had nothing to do with my personal history; Chinese was a way, I thought, to actualize a classic teenage yearning to ‘get in touch with my roots’. Turns out it was torture.

As many of you probably know, written Chinese is a non-phonetic pictographic system which means you have to straight up MEMORIZE four-thousand characters to be literate. Each character has anywhere from one to thirty-six strokes. EACH. As soon as I left high school and the pressure of grades to keep me absorbing and retaining, I promptly forgot everything. Everything, that is, except how to speak.

Fast forward a decade or so and I find my work has landed me back in China for the long haul. My spoken Chinese has picked up over the years but I’m still relatively illiterate. And as the use of cell phones and texting/chatting rises in China – even amongst my old masters – I’ve had to rely on a host of translation software to help me. The best (free) one so far is Google Translate.

I’d usually send a text to a master using Google Translate and when he wrote back, I’d ask a friend to read the Chinese out loud to me. Sometimes there were obvious miscommunications, but nothing we couldn’t solve with an actual phone call. It wasn’t until I started translating their texts and emails into English that I felt a sudden horrific awareness of the software’s limitations. I had been blindly putting my faith into this program to do the most important thing for me: communicate.

What?

And, what?

If that’s what computer translation had done to their words, what had I been saying to them?

Of course, somewhere in the back of our heads aren’t we all aware that translation isn’t perfect? Even the most bilingual translators in the world can’t produce an exact duplicate of meaning simply because languages aren’t just a sets of parallel words; it represents so many other possible differences such as culture, societal norms, emotional realities, histories, geography, political systems, ideologies, religions, etc. And even if we’re working in the same language, how can we ever be sure that what we say is what is exactly perceived on the other end? We can’t, because translation is so often a one-way street. Then why was I so shocked at my masters’ mangled texts?

For this week’s readings on glitch and deformance studies, I’ve chosen to fuck up/with Google Translate. To be sure, I’m not the only one who has been burned by the seductive promise of free translation. An estimated 200 million people are using Google Translate around the world every day[ii]. Do they know about Google Translate’s inherent incapabilities? Do they trust it blindly as I once did? Are they aware but still, like me, using it because of practical and financial reasons? What does this reliance on translation software mean in a greater context? It may mean that everyday, 200 million messages are being communicated incorrectly.

In Google Translate’s informational video, they explain how their translating program works:

Instead of trying to teach our computers all the rules of a language, we let our computers discover the rules for themselves. They do this by analyzing millions and millions of documents that have already been translated by analyzing millions and millions of documents that have already been translated by human translators. These translated texts come from books, organizations like the UN and websites from all around the world. Our computers scan these texts looking for statistically significant patterns – that is to say, patterns between the translation and the original text that are unlikely to occur by chance. Once the computer finds a pattern, it can use this pattern to translate similar texts in the future. When you repeat this process billions of times you end up with billions of patterns and one very smart computer program.

To me, this method exposes a host of issues, which the video does touch on but very very briefly. The ‘frequency of documents’ and therefore the quality of the translation depends on a number of variables; not just the preponderance of the language in question but language pairs as well. If the United States and China are trading more documents than say, Lithuania, then English to Mandarin translation will most likely fair better than English to Lithuanian. And, what kinds of documents are these? If many of them come from the UN as explained in the video, what kind of language patterns are most frequently found? What kind of language patterns are not found? How can we, the user, know what it does better or worse? How do we expose this system of its breakdowns and our expectations of perfection?

In Menkman’s manifesto on Glitch studies and Glitch art, she describes the glitch as having “no solid form or state through time; it is often perceived as an unexpected and abnormal modus operandi, a break from (one of) the many flows (of expectations) within a technological system”. (Menkman 341) The glitch is what exposes our unconscious expectation of a system: Neo’s déjà vu in The Matrix. I like that Menkman doesn’t see this as a negative thing entirely, but a catalyst for creation. “A negative feeling makes place for an intimate, personal experience of a machine (or program), a system exhibiting its formations, inner workings and flaws. As a holistic celebration rather than a particular perfection these ruins reveal a new opportunity to me, a spark of creative energy that indicates that something new is about to be created.”(341)

Jerome J. McGann and Lisa Samuels suggest a similar method to glitch art, but apply it to literary studies and call it Deformance. They argue that, “most ‘antithetical’ reading models operate in the same orbit as the critical practices they seek to revise: when critics and scholars offer to ‘read’, or reread, a poem, they hold out the promise of an interpretation.” (McGann & Samuels 2) Instead, they suggest subverting our methods of close reading and even anti-close reading by moving past interpretation altogether. They do this in the performative realm and suggest Emily Dickenson’s ‘reading backwards’ as a starting point. It’s a way to get us out of our ruts and into estrangement. It’s glitch theory as a theory. Instead of just reading my transfigured paragraph as a way to defamiliarize and expose our implicit trust of a system, they probably would have urged me to then analyze this new deformance as a work unto itself.

Mark Sample, however, has no desire to merge the performative and the deformed. Instead, he encourages us to leave it there, mangled, transfigured and deformed. He doesn’t “want to put Humpty Dumpty back together again.” And while he cites deformance as a move in the right direction, he believes the theory is actually just another derivative of our habitual ‘searching for meaning’ because, ultimately, it circles back to the original text or creation of meaning. In Sample’s deformed Humanities, “the deformed work is the end, not the means to an end.” Perhaps he’d like that initial nonsensical paragraph by Gaonkar and Povinelli the way it is.

So how do we glitch it? Fuck with it? Deform it and let it stay that way? Break the flow and disrupt our expectations? Well, we could do worse than to start here:

The Fresh Prince: Google Translated (Personal Fave)

Strange Pattern Glitches in the Program

As this week wore on and I began playing with Google Translate, experimenting on the quality of translation for certain languages and certain passages from different types of texts, it also became clear to me that perhaps Google Translate is a form of ‘reading backwards’ or deformance. There is a beauty in the estrangement with which we encounter our language again and can bring us new insights or understandings not only about the text but about language.

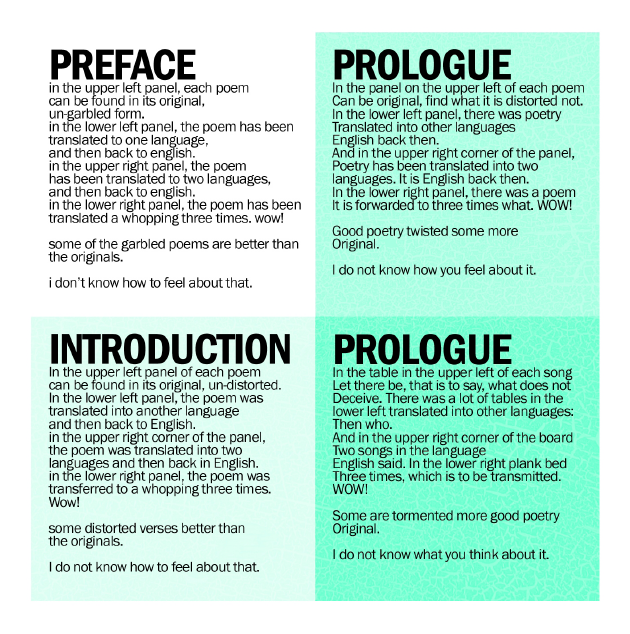

Take this ebook for example: 10 Poems Ruthlessly Mangled by Google Translate. The book simply takes ten poems and shows them in various states of transfiguration; one, two and three times through the translator. The intro states “some of the garbled poems are better then the originals. I don’t know how to feel about that.” (2) Or transfigured twice, “Good poetry twisted some more Original. I do not know how you feel about it.”

Selections from the ebook:

To me, all of these glitch art pieces and deformances do exactly what glitch studies promises. We are yanked into awareness by the hilarity, the unintended uses, the glitches. There is a beauty in the breakdown. To me, the most beautiful realization these methods and deformances show us is not only the fragility of a system, but of language, transfiguration and communication itself. We are our own imperfect translation computers impossibly slinging miscommunications everyday.

“Just as Foucault states that there can be no reason without madness, Gumbrecht wrote that order does not exist without chaos, and Virilio stated that technological progression cannot exist without its inherent accident. I am of the opinion that flow cannot be understood without interruption, or functioning without ‘glitching’. This is why we need glitch studies.” (Menkman, 344)

[i] Gaonkar, Dilip Parameshwar , and Elizabeth A. Povinelli. “Technologies of Public Forms: Circulation, Transfiguration, Recognition.” Public Culture 15.3 (2003):394

[ii] http://news.cnet.com/8301-1023_3-57585143-93/google-translate-now-serves-200-million-people-daily/

References:

Gaonkar, Dilip Parameshwar , and Elizabeth A. Povinelli. “Technologies of Public Forms: Circulation, Transfiguration, Recognition.” Public Culture 15.3 (2003): 385-397. Print.

Menkman, Rosa. “Glitch Studies Manifesto” Video Vortex reader II: moving images beyond YouTube. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011. Print.

Shankland, Stephen. “Google Translate Now Serves 200 Million People Daily.” CNET. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Nov. 2013. <http://news.cnet.com/8301-1023_3-57585143-93/google-translate-now-serves-200-million-people-daily/>.

Sample, Mark. “Notes Towards A Deformed Humanities” SAMPLE REALITY. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Nov. 2013. <http://www.samplereality.com/2012/05/02/notes-towards-a-deformed-humanities/>.

“Informational Video.” Inside Google Translate Google. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Nov. 2013. <http://translate.google.ca/about/>.

The post Google Translate: Glitch Art and Deformance Methods appeared first on &.

]]>