The post Cummins v. Bond: Unmaking the Author appeared first on &.

]]>On the day of July 23, 1926, a strange case passed before Judge Harry Trelawney Eve. On the surface, it seemed like a pretty straightforward matter of copyright in which one Geraldine Cummins was contesting the rights of one Frederick Bligh Bond to a work called The Chronicle of Cleophas. The thing is: Geraldine Cummins was not claiming that she had authored the work instead of Bond; she was saying she was the medium through which the work had been channelled.

The Chronicle of Cleophas, asserted Cummins, had been received incommunicado with the spirit world through the interface of a Ouija board, over a period of about a year or so, and usually in response to questions she had been hired to answer by clients as a paid medium. As for the defendant, Frederick Bligh Bond was employed by Cummins as an assistant and had acted as amanuensis to the various Ouija board messages being received by the medium; in the words of Jeffrey Kahan, “for each of Cummins’s Spiritual communiqués, he [Bond] ‘transcribed it, punctuated it, and arranged it in paragraphs, and returned a copy of it so arranged to the plaintiff [Cummins].’ He further stated, and Cummins did not contradict his statement, that he, Bond, ‘annotated the script, and added historical and explanatory notes’” (92). If you’re confused at this point, you’re not the only one.

We have here a literary shell game, in which authorship is shuffled about until the client is utterly baffled. The difference is that, in a shell game, the client (or “mark”) understands who is doing the shuffling. In the case of a séance no one seems to be the creative center . . . The multiple hands recording the Spirits creates the impression that the creative center is not physically present (Kahan 91).

Who, then, did Judge Eve decide in favour of in 1926 — the medium who channelled the work, or the scribe who wrote it down, arranged, and edited it? And why should we care?

“Walk through a museum. Look around a city. Almost all the artifacts that we value as a society were made by or at the order of men. But behind every one is an invisible infrastructure of labor — primarily caregiving, in its various aspects — that is mostly performed by women.” In her 2015 article “Why I Am Not a Maker,” Debbie Chachra challenges a cultural attitude that privileges the act of making over the more invisible acts behind it, particularly the gendered acts of caregiving and educating. Walk through a text. Look around at the letters and words and margins and paper. It was the mediums of mid-19th-century Spiritualism — an almost across-the-board female labour force — who presented a challenge to one very highly traditional order of men, namely, the order of the author.

What finally materialized in a court of law in 1926 was a practice that had in fact been a booming industry since the Fox sisters started charging admission to rappings on tables in 1848 and mediums started channelling under the moniker of Spiritualist and publishing under the monikers of spirits, which was, according to Bette London, “for some the only way to put themselves forward as authors” (152). This is a practice that literalizes Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar’s statement that “[a] wealth of invisible skills underpin material inscription” (245). The case of Cummins v. Bond is not so much a case that brings to the fore the act of making, nor does it propose a refusal to be a “maker” as Chachra puts it, but rather the act of unmaking.

For the purpose of this probe these themes will remain a little superficial, but the surface is the best place to start here. The title The Chronicle of Cleophas, throughout discussions of Cummins v. Bond, remains just that, a title without a content — the book is rarely considered in its own right and finding a copy of it leads to a ghost town of an Amazon.ca page where The Scripts of Cleophas is (hauntedly) housed. This is exemplary of research into automatic writing, the products of which are sometimes so illegible they cannot even be read, as in the invented language of medium Hélène Smith, who called her script “Martian.” Automatic writing, also called psychography or spirit writing, offers a process of writing in lieu of a product (the continuous verb writing rather than its gerund), and furthermore a process of writing in which the produced work is secondary if not tertiary to the act of creating it; a “transitional object” that connects the “sensory body knowledge of a learner to more abstract understandings” (Ratto 254, emphasis his own).

In his 2011 paper, Matt Ratto outlines his experiments in “critical making,” which address a “disconnect between conceptual understandings of technological objects and our material experiences with them” (253). I was struck by how closely the drawbot, which Ratto had his participants construct in one of his workshops, resembles the planchette that automatic writers used during séances in the 19th century. Whereas the drawbot moves across the paper by a process of mechanization via a small motor, the planchette moves across the Ouija board or piece of paper by a process of automaticity via the participant’s hand, part of what the Spiritualists called channelling, or what a cognitive scientist may call ideomotor action. My main question here is, how could the Spiritualist practice of automatic writing be revived and refigured as a model of critical making — where critical making combines critical thinking, a less goal-oriented form of “making,” and conceptual exploration (Ratto 253)? What would this look like and what are the “wicked problems” it could address?

In my last probe, I explored how sleep could be an interesting object of exploration for a Media Lab; automatic writing by contrast offers a methodology rather than an object — not so much the axis around which questions can be posed, but a way to create the questions in the first place. As sleep unmakes waking and any easy notions around consciousness, automatic writing unmakes the author-function and any easy notions about what it is to write.

The real difficulty is who or what is “Cleophas.” If it be assumed (which nobody can prove) that “Cleophas” has a personal identity of his own and could have been the author of the writing, his evidence would be material. “Cleophas” might be sworn and cross-examined by the process of automatic writing. Instead of being difficult, this might be no trouble at all. Once “Cleophas” is accepted as a real person, the problem of communication involved in swearing him and examining and cross-examining him very likely would not be as difficult . . . (Blewett 24).

Who or what is “Cleophas”? What is automatic writing? How does it work? Is it a shell game, as Kahan suggests? An experiment? A literary device? The fact that the above quote comes not from literary criticism, but The Virginia Law Review, 1926 edition, is indicative of the ripples Cummins v. Bond was causing in terms of conceptions around authorship, marked not least by the quotation marks unrelentingly hovered around the Cleophas in question. “Cleophas,” we could say, is an assemblage, as is, we could also say, any “writer,” as is any piece of “writing.” In “What Is an Author,” Foucault discusses how the 19th century saw the rise of a figure who was not just an author of a text, but an entire discourse, such as “Freud”; “Marx” (228); at the same time, the practice of mediumship that cropped up with automatic writing composed the other side of the spectrum of this canon, folded it back, threw a mirror up to it, but one that hardly anyone was able to see. In the case of Cummins v. Bond, it was the medium Geraldine Cummins who came out victorious, and not Frederick Bligh Bond who’d physically held the pen to record the text. But what is not recognized in either the resolution of this case or the Amazon.ca screenshot above is that on the title page of The Scripts of Cleophas, Geraldine Cummins credits herself as “recorder,” not as “author.” Though she won the case, she was still not granted the right to self-representation. According to Jeffrey Sconce,

Long before our contemporary fascination with the beautific possibilities of cyberspace, feminine mediums led the Spiritualist movement as wholly realized cybernetic beings—electromagnetic devices bridging flesh and spirit, body and machine, material reality and electronic space (27).

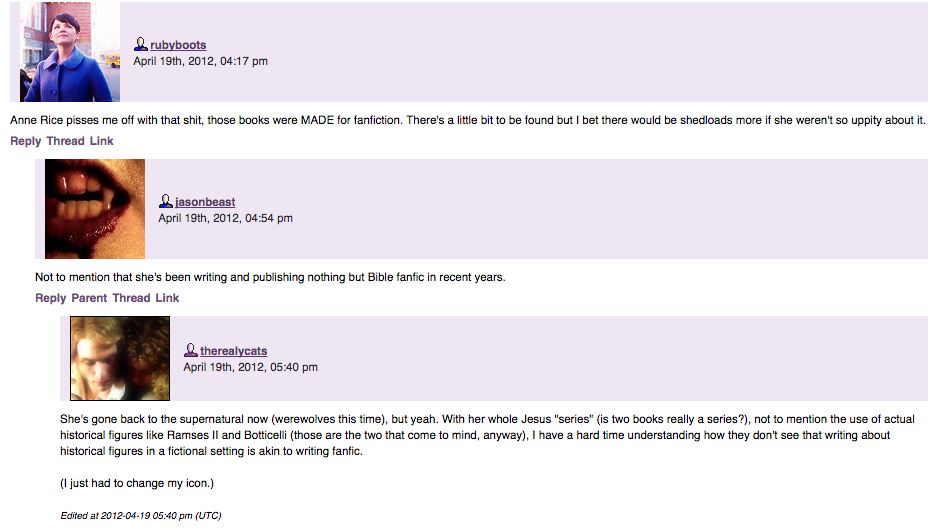

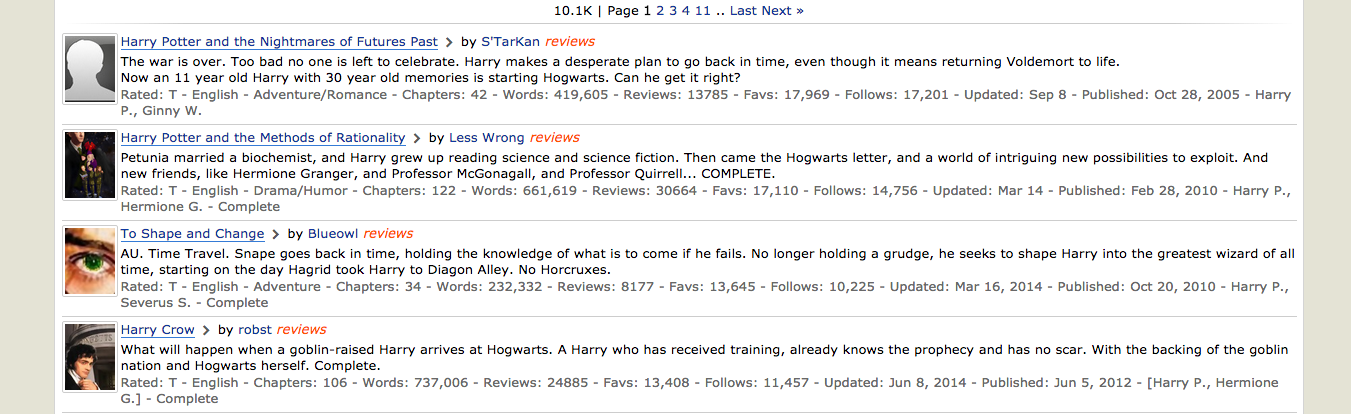

It’s a seductive notion, but, really? The mediums of 19th-century Spiritualism often published under the male names of the spirits they were channelling and thus, as London pointed out above, were able to publish at all, and furthermore earn a living for themselves in a position of power as mediums. The history of automatic writing, in contrast to Kahan’s statement, is physically present. These days, our automatic writers are quite literally transitional objects, drawbots: in 2014 alone, one billion stories were generated by Automated Insights’ Wordsmith program (Podolny), which uses NLG algorithms to “write” articles, while tamed automata are often gendered female, such as Siri, Archillect, “Her.” The embodiment of work and working is changing, and so are the questions surrounding it. How could a writing process that is seen as plural from the get-go change discussions around copyright? What does automatic writing say about fanfic, for example, or creativity, labour, or the ways in which these categories are parsed out according to gender? Finally, if the question, as Bernhard Siegert proposes, is no longer “how did we become posthuman? But, how was the human always already historically mixed with the non-human?” (53), then maybe we can also ask: is there any writing, has there ever been, that is not automatic?

Works cited

Blewett, Lee. “Copyright of Automatic Writing.” Virginia Law Review 13.1 (November 1926): 22–26.

Chachra, Debbie. “Why I Am Not a Maker.” The Atlantic, January 23, 2015.

Foucault, Michel. “What Is an Author?” [1969]. Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews by Michel Foucault. Ed. Donald F. Bouchard. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977: 113–38.

Kahan, Jeffrey. Shakespearitualism: Shakespeare and the Occult, 1850–1950. New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1979.

London, Bette. Writing Double: Women’s Literary Partnerships. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999.

Podolny, Shelley. “If an Algorithm Wrote This, How Would You Even Know?” The New York Times, March 7, 2015.

Ratto, Matt. “Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Social Life.” The Information Society 27 (2011): 252–260.

Sconce, Jeffrey. Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2000.

Siegert, Bernhard. “Cultural Techniques: Or the End of the Intellectual Postwar Era in German Media Theory.” Theory, Culture & Society 30.6 (November 2013): 48–65.

The post Cummins v. Bond: Unmaking the Author appeared first on &.

]]>The post Embodied Space: The Webster Library Transformation appeared first on &.

]]>The Webster Library Transformation is underway and in the University’s postings about the work being done, the word ‘renovation’ is conspicuously absent possibly because it carries connotations of disrepair, age and maintenance of an old system. Maybe that’s also why it’s being touted as a “next-generation” library, which makes a kind of avowal of the timeliness of the library but also sounds like the unveiling of a new IPhone.[1] It’s similar to the previous version but somehow entirely life changing, transformative. It should not only bring us into the present age but it should project us into a time beyond our own. The library reprogrammed as scholastic utopia. The language used to describe the library’s changes is utopic in this sense that through innovation we will be taken into a new space, a hitherto imagined space that brings us not only into a different physical location, but projects us into a different conceptual space. I think the choice of the word transformation is apt and that the library will not only change the way we work and produce work as students, but as I would like to explore in this probe, the library transformation reflects and is an articulation of an already occurring shift in the way we conceptualise knowledge, the creation of knowledge and the identity of the student.

The Second floor

My preferred study space has always been the carrels (I prefer ‘cubes’) in the silent reading zone of the second floor along the windows that look down on Bishop street. The carrels are designed for the kind of individual writing work I need to do. The partitions separating each table and chair connect each student but also shields them from each other’s view. The walls act kind of like horse blinders or ‘blinkers’ as they are sometimes called, blocking out potentially distracting stimuli and directing the gaze front and centre. Sometimes I lean forward for maximum immersion or back to escape the feeling that I exist only within a word document. In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard’s meditates on corners, describing this type of space fondly as a “half-box, part walls, part door” (137) a space whose construction ensures immobility and allows us to “inhabit with intensity.”(xxxviii) Bachelard claims that the only we learn how to do this by occupying these corner spaces where imagination is seemingly everything. For me this silent, ascetic method of work and student has been part of the identity of an English student. But it can also be isolating. I wonder if my work sometimes reflects the circuitous trains of thought going on in my conceptual space or the narrowness of my work space. In I wonder if I am ‘blinkered’. I can’t help but think there is something like this going on when I am cloistered in my cubicle with my texts and my lecture notes trying to construct something of value. If the texts, the tech and the Profs are actors that influence our work then why not the spaces we produce our work in as well? In looking at the library transformation I began to see how a complex set of relations between people, objects, space and time can perform or express ideological work that informs the academic work being done at the University.

“Space that has been seized by the imagination cannot remain indifferent space subject to the measures and estimates of the surveyor.” (Bachelard, xxxvi)

The Third Floor

As I entered the new floor of the Webster library I was sceptical, I liked my claustrophobic little cube. I had only seen digital projections of a modern looking near-bookless library populated with ghostly students. Going up to the third floor was an ambivalent experience. I couldn’t help but be struck by the vast improvement in overall aesthetics of the third floor. The lighting was bright but soft, the lines of the furniture and shelves clean and new and the colors were not stale and drained of life. And yet the territory is slightly bewildering. Walking through the library I noticed the main difference between the second and third floor is a more open concept which gives the feeling of spaciousness although the study spaces are as close or closer together than in some areas of the second floor. Maybe this is an illusory distinction caused by the partitions in the old carrels, which have the effect of creating a bunch of little microcosms of student space. The library transformation was borne partially from a crisis of space, so it will be interesting to see how the individual, somewhat bulky space of the carrel is re-imagined.[2] This ties in with the second big difference: visibility. On the third floor you are always visible to everyone around you. The room is bounded by two glassed-in silent reading rooms with completely open tables. The workspaces are individual but communal at the same time. In between these rooms there is an open concept study area with ikeaesque tables, chairs and sofas. Talking is permitted, some students work alone along the wall looking down into the library building and others work in groups around the tables writing figures on a whiteboard. In the middle of the room there are three big glass rooms that resemble aquariums that contain groups of students working together.

For the library to do the work of a library, it must be constructed around clear delimitations. The different configurations of space must prescribe different types of behaviour. The more ingeniously these spaces are designed, the less visible the work being performed becomes.[3] The traditional library job of shushing has transformed from a slightly Orwellian image of a woman pressing her finger to her lips to an androgynous grinning emoji type symbol. Library Special Projects Manager Brigitte St. Laurent-Taddeo was kind enough to show me around and informed me that next to space two of the biggest concerns of the project was improving light and addressing noise. Concordia even hired an acoustician to find out how to promote a quiet space. The ingenuity of this floor is that in addressing the issue of light by replacing walls with glass, the visibility of the students seems to make them more prone to self-monitoring their noise levels. Even in the collaboration space students speak in hushed tones.

In “Of Other Spaces” Foucault describes sanctification of space as “inviolable” oppositions embedded in the space itself. These oppositions of silence and noise, inside and outside, together and separate are of paramount importance to the library and the new floor’s construction makes us those (almost) perfect little door closers. I would argue that the quality of a library depends upon its status as a somewhat sacred space, where these rituals of work, these “rites and purifications” (26) have to be observed to occupy the space and make way for the production of knowledge. “Heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing which both isolates them and makes them penetrable.”(26) The visibility of the student at all times allows us to perceive the needs of the other student and our own interest in respecting them by being silent. When the walls of the carrels are removed, we do the work of the walls. The design of the room demands that we keep out of each other’s workspace.[4] Transparency has also been a factor in the construction of the new library spaces through the Webster Library Transformation Blog. Students are now more aware of the changes made in the configuration of space while it is happening and encourage student input. This is also indicative of the kind of student of the new library, simultaneously and seamlessly utilizing virtual and physical space and making them communicate and improve upon each other.

Perhaps this new mode of thinking and producing transparently betrays the movement from one kind of student to another, but also another way of seeing the pre-existing connections between ideas, people, disciplines and techniques that can encourage innovation and understanding. Transparency could do away with the opportunities for glitches to hide in the system, to do away with biases of knowledge and make it easier to revise and critique our thinking. In Star’s “The Ethnography of Infrastructure” we have seen how transparency is arrived at through failure of the system and crisis. The library transformation came about partly from a crisis of space but also made visible the infrastructure of knowledge production. The transformation is also an opportunity for each tiny decision to nurture and influence the changing academic environment in its uncertain and hybrid form.

“In the everyday world, it is of shattered, scattered sacredness that we must speak […]” -Marc Augé, “An Ethnologist in the Metro.”

Naming is also important to note. The reading rooms in the third floor are named after countries namely, Kenya, France, Netherlands, Vietnam and India. In Marc Augé’s study of the Paris metro he notes the way that the historical names of the metro stops have shifting significations for different users and generations of users.[5] The naming of the reading rooms eschews the local in favour of the global. Library Special Project Manager Brigitte St. Laurent-Taddeo was kind enough to show me around and explained that the choice of countries corresponds to research done on the cultural backgrounds of the student population at Concordia. She also mentioned that the naming has not gone unnoticed by students and they’ve taken to referring to the rooms by their international names. This is indicative not only of the diversity of the students but also of the widening of scope from the local, historical to the global and mobile. The West is potentially dethroned as the priveledged centre of knowledge production. Foucault argues that “The museum and the library are heterotopias proper to Western culture of the nineteenth century.” (26), however the twenty first century sees the access to that wealth of knowledge broadened by our access via digital archives which makes us mobile, living libraries. At the same time that certain rites have to be performed to utilize the space, there is a corresponding de-sacralization of the library as site of knowledge. A corresponding change in physical access to books may be coming as the library aims to make more space for student. That student also occupies a different kind of space emerging from the individual space of the lone genius to the public and social space of the “next-generation” library. There is no arcane knowledge in this space, or rather it has lost its position of power in favour of the everyday as the cultural ground shifts, hierarchies of knowledge slip, high and low culture is renegotiated. Moreover the process of how these valuations of knowledge come to be is made visible and studied. This change in the conception of knowledge might mean the disappearance of a certain type of scholar or simply the transformation of his work.

“In other words, we do not live in a kind of void, inside of which we could place individuals and things. We do not live inside a void that could be colored with diverse shades of light, we live inside a set of relations that delineates sites which are irreducible to one another and absolutely not superimposable on one another.” –Foucault “Of Other Spaces”

The stacks themselves are also a part of the transformation. The collections movement from the second to the third floor necessitated a paring down of the books. The task of ‘weeding’ removes from the collections all redundant, out-dated and damaged books and donating them to an archive or another institution. The out-dated books fascinated me the most, to imagine all the once relevant ideas in those books becoming artefacts is part of the process of knowledge making but still chills me but even to be wrong means one is playing a part in the creation of knowledge and that some can only hope to be a blip on the academic radar.[6]This pruning of material betrays the already apparent role of artefact, the books have been assessed by the decreasing frequency with which they are requested, and their unpopularity pointing to newer modes of thought; their removal is just the solidification of their non-agency. Although the library assures me that they never simply throw out books, I can’t help but wonder if anything is lost in the increasing digitization of documents. Increasingly, students can access information across different mediums and using new tools, which entail a different experience of learning.

The new library has also added two different types of spaces with the express purpose of showing work, The Multipurpose Room and the Visualization Room. Both rooms provide students with the use of equipment and space designed to share their projects. The inclusion of this room speaks to the imperative to have our work be visible so that others can interact with it. The use of a variety of techniques that crosses disciplines, allows different disciplines to perceive existing connections between areas of study. We see this at work in the MLab, as the different tools and theoretical lenses used take Joyce’s Ulysses beyond the English Lit stacks and seminars. It also speaks to the benefit of visibility in academia through the diffusion of work on blogs and social media. Once mostly a tool for mediating our personal lives, the growing authority of these types of forums allows work to traverse boundaries of academic prestige, defy categories of discipline and exist in experimental forms. And now to digress to another space…

Ninth Floor, Hall Bldg

An incident in the University’s history elucidates articulations of space, transparency, visibility, infrastructure, technology and access to knowledge.The Computer Centre Incident of 1968 was a student riot incited by allegations of racism directed at six West Indian biology students from a faculty member. After talks degenerated at a Hearing Committee formed to investigate the charges, two hundred students occupied the computer centre in the Hall building. Over the next two weeks negotiations were carried out almost to the point of a compromise but failed just as half the students left the protest, the argument reignited and the remaining one hundred students carried out their threat to destroy the computers, causing extensive damage to the building as well. There are many things that are interesting about this story is the way the public space is contested and shown to be already a part of the political and ideological struggles at the university. The student’s choice to occupy the computer centre and threaten the technology in order to leverage their claims shows that they perceived where value and power was situated spatially in Concordia. What is demoralizing is that they wanted recognition of injustice so badly that they would destroy the very spaces and objects that were integral to their own research and identity as students. This incident resulted in the arrest of students, the eventual reinstatement of the accused faculty member and millions of dollars in damage. The computer lab is still on the ninth floor of the Hall building and no traces of the riot remain but the conflict resulted in the re-organization and institution of student representation and a restructuring of policies and codes that govern university life. Interestingly, the Paris protests were happening at the same time, students occupied the streets and took to turning over cars when they couldn’t get their institutions to cooperate. The ideological changes though not completely effected, can be communicated through violence to space. At the same time, the anarchic violence to space is an attack on an expression of ideology, power and forms of social ordering.

Today space at Concordia is increasingly heterogeneous and political and ideological action is intrinsic to the construction of space. If we look at other spaces in the University, memorials, cafes, corners, thresholds, we can see how structure and design can redistribute power to the students. There are as many struggles, stories and resistances as there are spaces in Concordia. The library transformation’s policy of transparency and ongoing construction gives us the opportunity to contribute our own ideas and opinions. Even better the library is an extension of the classroom; part lab, part experiment, a heterotopia that belongs to everyone and no one.

[1] Webster Library Transformation Blog

[2] “At present, only .57 m2 of space is allocated for each full-time equivalent (FTE) student. This ranks as the lowest space per FTE among comparable Quebec and Canadian university libraries.”[2] https://library.concordia.ca/about/transformation/

[3] See Star’s The Ethnology of Infrastructure.

[4] Law, “Notes on the Theory of the Actor Network: Ordering, Strategy and Heterogeneity.” Concept of strategies of translation improving network strength. (6)

[5] Auge, “An Ethnologist in the Metro” (275)

Works Cited

“Webster Library Transformation.” Libraries. Concordia University, 5 Mar 2015. Web. 1 Nov 2015.

“Collection Reconfiguration Project: One large step towards a healthy collection.” Webster Library Transformation. Concordia University, 2 Feb 2005. Web. 1 Nov 2015.

“Our vision for the Webster library.” Concordia University, 19 Nov 2014. JPEG.

“Computer Centre Incident.”Records Management and Archives. Concordia University, Feb 2000. Web. 5 Nov 2015.

Augé, Marc. “An Ethnologist in the Metro.” Journal of the Twentieth-Century/Contemporary French Studies.

Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. Boston: Beacon Press, 1958. Print.

Foucault, Michel, and Jay Miscowiec. “Of Other Spaces.” The Johns Hopkins University Press. 16.1 (1986): 22-27. JSTOR. Web. 1 Nov 2015.

Law, John. “Notes on the Theory of the Actor Network: Ordering, Strategy and Heterogeneity.”Center for Science Studies Lancaster University. (1992): 1-11. Web. 5 Nov 2015.

Sayers, Jentery. “The Long Now of Ulysses.” Maker Lab in the Humanities. 21 May 2015. Web. 7 Nov 2015.

Star, Susan Leigh. “The Ethnography of Infrastructure.” American Behavioral Scientist. 43 (1999): 377-389. Sage. Web. 2 Nov 2015.

St. Laurent-Taddeo, Brigitte. Personal interview. 11 Nov 2015.

The post Embodied Space: The Webster Library Transformation appeared first on &.

]]>The post Sleep, a laboratory appeared first on &.

]]>“Yet these analyses, while fundamental for reflection in our time, primarily concern internal space. I should like to speak of external space.” —Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces”

“What will the creature made all of seadrift do on the dry sand of daylight; what will the mind do, each morning, waking?” —Ursula K. Le Guin, The Lathe of Heaven

1a) Space

If you happen to be in Lausanne, Switzerland, and if you happen to be at the Centre hospitalier universitaire vaudois in Lausanne, Switzerland, you can take the elevator six floors down from the main floor—yes, that far, to the basement, to the basement of basements—and find yourself at a place called the Centre d’investigation et de recherche sur le sommeil (CIRS), and this is where we’ll begin.

CIRS comes alive at night. If you walk inside, you’ll see that five closed doors fold around a night nurse sitting in the middle of five screens. Behind each closed door is a room that looks identical to the other four: like a bedroom or like a simulation someone created of a bedroom, but with cameras hooked up to the walls and a cornucopia of heteroclite gadgets hinging sleeping bodies to bedside units. These sleeping bodies appear to be armoured in wires and tapes and their breathing patterns are rhythmic and deep under the quilts.

On the screens that encompass the night nurse, data from the sleeping bodies is projected, external mirrors of the internal.

This is the place where sleep has come under surveillance. Not as something that happens or as something that one does, but as something that happens wrong, that one does badly. In fact, being bad at sleep is the act that both isolates this space and makes it penetrable (Foucault 26), it’s what allows you entrance at all.

The heterotopia (of deviation) of the sleep clinic is the object of this probe, but actually it’s possible to go a bit further—it is the snow globe that you shake and look into at the scene within, it is the peephole, the CCTV into the heterochrony of sleep.

Here, the private act of sleep, a space of complete alone-ness where we spend one third of our lives, is made public and populated in the arena of the faulty body’s data.

1b) Time

Sleep is a behaviour. As such we can say it exists in a special relationship to time. It is daily and ahistorical, it is a routine that has multiple other routines orbiting it, like flossing, washing, putting on that old T-shirt before going to bed, even waking up, drinking coffee. Yet in order to study sleep, science has made the behaviour into an object, or what Bruno Latour, quoting Gaston Bachelard, might term a “reified theory” (66). Polysomnography is the inscription of sleep, and it comes through the interface of programs such as Somnologica, which present a montage of continuous lines compartmentalizing the messiness of the living body, each into a particular graphy (for the brain/mind, electroencephalography; for the heart, electrocardiography). A portrait of sleep in electroencephalography, for example, is drawn mostly in delta waves (𝛿), theta waves (θ). Polysomnography is the mirror cast up to sleep, where knowledge is formed from a space in which “knowledge” has traditionally been seen as momentarily suspended.

Now we can know sleep, construct it. In the uncanny valley of the data of our bodies lie avatars of our sleeping selves: “I see myself there where I am not, in an unreal, virtual space that opens up behind the surface . . . From the standpoint of the mirror I discover my absence from the place where I am since I see myself over there” (Foucault 24).

Yet like an image in a mirror, sleep is fleeting: behind all the data produced by sleep research, the basic function of sleep remains mysterious, making sleep, as Allan Rechtschaffen notes, “the biggest open question in science” (Goode). In relation to the sleep clinic, then, how can we say that something is being done wrong when we do not even know what that thing is for?

What kind of place is this? How to read the self when the self is over there?

1c) They collapse

The establishment of the sleep clinic as a “real” space was a relatively slow evolution, but we can say it was minted around the time Allan Rechtschaffen and Anthony Kales put out a manual for sleep scoring in 1969 (Kroker 362–66). The clinical study of sleep gave way not necessarily to a breakthrough concerning the function of sleep, but to a massive industry, where, for example, you can pick from over seventy different drugs to “cure” your insomnia alone (the fact that sleep requires curatives at all is relatively novel, but by now a pretty stable concept).

These days it’s not only sleep that is of interest, but also sleeplessness, which is either seen as dangerous (“drowsy driving” anyone?) or desirable, as in current military research. About the latter, Jonathan Crary notes in his book 24/7: “Sleeplessness research should be understood as one part of a quest for soldiers whose physical capabilities will more closely approximate the functionalities of non-human apparatuses and networks” (2). The pathology of sleep, a societal construction built around an ahistorical event, has invited a species of questions that may not have existed previously; i.e. is it possible to function outside of sleep altogether? If so, what kind of heterochrony would that be? (One that needs in any case a longer probe…)

2) A possibility of networks

The science of sleep brings to light an event where the internal intricately aligns to the external: where a private and invisible behaviour becomes public and reified.

Yet the data sleep gives up is difficult to read, somewhat like deciphering bits and pieces of the Voynich manuscript; sleep is asemic and maybe that’s where it will stay. If the heterotopia par excellence is the ship, as Michel Foucault posits (27), then the data washing up from the heterotopia of the sleep clinic is the mess of the ocean fossilized and frozen, seadrift on the shore of the waking.

And maybe, this makes the study of sleep rife for other laboratory models, ones more similar to those Jentery Sayers describes in relation to the infrastructure of the Maker Lab in the Humanities at UVic; that is, labs informed as cultural practices, where a “research team performs or practices multiple definitions of a given field.” How could such a space open an area of research where sleep is not necessarily pinned down to biological data, but where this data, such as that produced by polysomnography, is one point in sleep’s movement (Foucault 23)?

I was granted access to the heterotopia of the sleep clinic not through the pathological (although that could be a funny way to put it) but through an outside foundation that placed me in the lab as a resident poet. Like Jentery Sayers’s MLab, this lab was separated into two physical places: the Center for Integrative Genomics (CIG) at the University of Lausanne, where foundational research on sleep is carried out, and its clinical component described here in text and pictures, where patients are treated and their data collected and filtered back down to the CIG. As one person in the lab carrying out a vastly different kind of research than the others, I found the exchange of information to be mostly asymmetrical: while I learned a lot from the scientists, I was often seen as a curiosity and sometimes as a personified affront to the state of research in general, and there were at least two occasions when I was approached by a colleague with the sole purpose of telling me they didn’t read poetry (“um… thanks for letting me know…?”). It was clear, though, attending meetings, participating in experiments, speaking to technicians and lab directors and nurses and doctors and postdocs, that sleep was proving more elusive than the sum of the efforts being deployed; furthermore, the fact that I was put into this situation at all suggests that the need for broad collaboration was and is being recognized.

How then could a laboratory configured as a “network that connects points” (Foucault 22) offer a different perspective on a concept like sleep, and what would this look like? How does altering the research method change the research object? Because maybe sleep, as it is currently being studied, will not give up its secrets; maybe sleep is asking for different kinds of questions and we require different ways of posing them.

Or maybe, taking a page from science fiction, sleep itself is the laboratory and we the subjects under its study (cue spooky exit music).

Works cited

Crary, Jonathan. 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. London: Verso, 2013.

Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces.” Diacritics 16.1 (Spring 1986): 22–27.

Goode, Erica. “Why Do We Sleep?” The New York Times, November 11, 2003, http://www.nytimes.com/2003/11/11/science/why-do-we-sleep.html

Kroker, Kenton. The Sleep of Others, and the Transformations of Sleep Research. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007.

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979.

Le Guin, Ursula K. The Lathe of Heaven. New York: Scribner, 1971.

Sayers, Jentery. “The MLab: An Infrastructural Disposition,” Maker Lab in the Humanities | UVic, website, http://maker.uvic.ca/bclib15.

The post Sleep, a laboratory appeared first on &.

]]>The post The #HungerGames Function appeared first on &.

]]>Hunger.

Games.

A game about survival for food. A game of high consequences. In 2008, Suzanne Collins released a book titled “Hunger Games” that followed a young adult female protagonist who volunteers to take her sister’s place in a mandatory death match enforced by “the capital”, the Elite society that controls the fictional world of Panem.

So what does it mean to transpose this narrative into a sandbox game such as Minecraft? Can it even be called “Hunger Games”?

The questions we must ask before we begin our construction of a quote-on-quote “Hunger Games” arena are as follows:

What is Hunger Games? What makes Hunger Games, Hunger Games? Is it the narrative, the characters, the atmosphere, the environments? Can we simply reduce it to a Player-versus-player all out death match? How can we recreate the true essence of “Hunger Games” within Minecraft—is it even possible?

I found that often the hashtag “Hunger Games” is included in conjunction with multiple others. This use of Tags lures Hunger Games fan into joining a server that promises them the “Hunger Games” experience. The use of “Hunger Games” encourages fans to flock to the server. Could these servers only be “survival” games which have existed for a long time but are now under the guise of “Hunger games” as a means to encourage more players to join?

Commenting on my ideas on “Hunger Games” as a hashtag, Nic Watson says;

“Interesting how some of the graphic banners on that list show a subset of tags that doesn’t include ‘Hunger Games’, but ‘Hunger Games’ is in the text tags. Like they want to make it show up in HG searches but not actually promise HG. Maybe we should look at what tags are collocated with HG tags. Perhaps that could go under ‘variants’”

The “Hunger Games” games are usually included with various other mini games on one server including various PVP arenas, and Sky Block.

These are example of PVP/Hunger Game-like servers found under the tag “hunger games”:

* Play.mc-lengends.com

* Mcsimplegaming.com

* Mc.hypixel.net

* http://www.ubermc.net/minecraft-the-walls/

However, this last server is a little different from the other PVP servers above and specifies team work in order to win:

“Minecraft The Walls is a very unique server type. 4 teams divided by a walls that keep peace for the first 15 minutes of the game. During this first 15 minutes all the players on each team are given a specific class that allows them to help their team in different ways. For instance the alchemist can create potions for their team for when the walls drop. or the blacksmith that can forge weapons and armor using their anvil. Below each team spawn there are mines to be explored and resources to be exploited. Team work is crucial to winning this game as each player has a unique role. The last team to survive after the walls drop, wins the game” (The Walls).

Names and titles take on a life of their own online, both explaining the context and enticing players. But what can we say about these games that may not really be “Hunger Games” portrayals, but just PVP games using the hashtag Hungergames?

These servers are mainly focusing on the battle arena, the all-out district war (The annual Hunger Game) while overlooking everything else about the novel. In this way, what makes them any different from PVP?

In my graduate class we read sections from Michel Foucault. “What is an Author?” brings up a valid argument and question about the way players are using the key words Hungergames.

Consider this: are we, and everyone else who tags their Minecraft server, using the “author function” as a way to gain credibility and legitimization? What are we promising when we assign the hashtag #Hungergames to our game servers?

Foucault explains that “such a name [the author’s name] permits one to group together a certain number of texts, define them, differentiate them from and contrast them to others […] establish a relationship among the texts” (227).

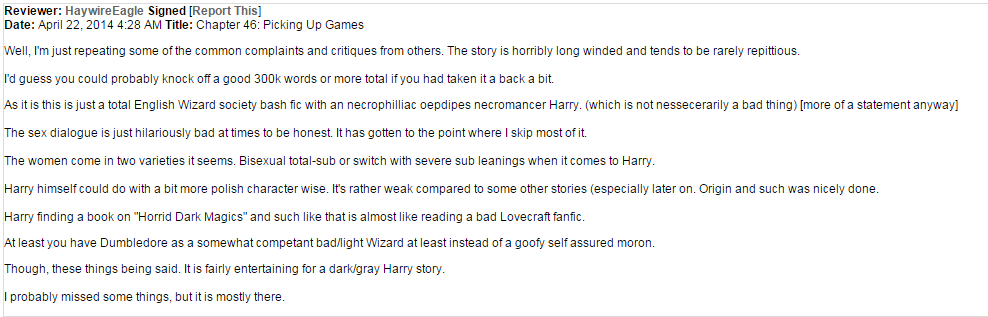

When talking about transmedia narratives, Game scholar Henry Jenkins explains that “Audience familiarity with this basic plot structure [read: knowledge of the narrative] allows script writers to skip over transitional or expository sequences, throwing us directly into the heart of the action” (Jenkins 120). While franchises create Transmedia narratives, Minecraft can work as a form of fan generated transmedia narrative that allows players to interact with aspects of the media they normally would not have access to. However, most of these #Hungergames servers reduce the narrative to a single moment: the arena battles—we are literally thrown into the “heart of the action”, however, are we trivializing the rest of the novel that looks into inequality, poverty, capitalism, et ect? Without a deeper understanding of the consequences (are there any consequences in an online game?) of the “Hunger Games” as portrayed in Collin’s book, can we actually be anything more than a PVP using a hashtag as a function to obtain and entice players?

What are we doing to Suzanne Collin’s “Hunger Games” novel by thus tagging these PVP servers? What can we do to create a more authentic server? Is it even possible to create a server worthy of the term “Hunger Games”?

In my next post I will look at a few ways we could construct our server with these questions in mind.

Work cited

Foucault, Michel. “What is an Author”.

Jenkins, Henry. “Convergence Culture : Where Old and New Media Collide”. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

The post The #HungerGames Function appeared first on &.

]]>The post Author and Authority: Creating Fashion Trends in Historical Re-enacting (Probe on Foucault’s ‘Author’) appeared first on &.

]]>As I begin my own process towards authorship, I have been thinking a great deal on how we create authorities out of persons who share their research. This has held exceptional resonance with me in my own work on Eighteenth Century fashion and how it is viewed by the community of re-enactors I belong to. When I began as a historical interpreter and costumer, I knew about the larger community, but did not feel a part of it. In Nova Scotia, we were a small group who did our own research and shared it with our friends, discussing and shaping ideas within a very small group (at that time, about 100 total members). With the dawn of the internet, and social media beginning with email list serves, our scope grew larger, we were now included within the larger, North American community. At that time, there were few opportunities for non-academics to publish their research. Some were able to write and publish books about and through their own local museum collections, others published articles in community newsletters. At that time, the status of the author rose to dizzying heights, they became superstars within the community and began to be noticed by the academic community. The research they published was copied extensively throughout the larger North American community with little regard to situational and cultural dynamics.

Fashion doesn’t exist in a vacuum, but neither does it exist as a wide spread phenomena. Even today, there are cultural differences in how we dress ourselves, even here in Canada. The cut of our jeans will be different in Nova Scotia than it is in Alberta, not only because our bodies are differently shaped but also because of how we wear clothing culturally. These differences relate to genetics, weather patterns, religion, and culture. In the 18th century, those cultural differences can be highly insular. What a person wore in Pennsylvania Deutch country would be different than what a Protestant Loyalist refugee would have worn on their way from New Jersey to Nova Scotia. Don’t get me wrong, fashion existed, and was not as stagnant as would first appear, but there are cultural, weather, situational, and religious differences at play. A person interpreting a figure from Nova Scotian history cannot just copy an outfit from ‘Fitting and Proper’ (Burnston, 2000) and be entirely correct.

Since the publication of this book, Sharon Burnston has become an authority on 18th century clothing. She has been given star status within the community. Others who achieved such status through early publication were not as considerate in their research though, and that research has proven to not be as reliable as Burnston’s book. Other books published in the same time frame include ‘Costume Close Up: Clothing Construction and Pattern, 1750-1790’ (Baumgarten, 1999), ‘Whatever Shall I Wear’ (Riley, 2002), and ‘Tidings from the Eighteenth Century’ (Gilgun, 1993). All these authors achieved star status, or authority, save for Mara Riley, despite her research being considerate and strong.

Each of these publications created fashion trends within the hobby. How can this be, when members of the community should be considering the context of the research and how it relates to their own interpretations of historical figures? It seems that modern capitalism and desire can influence how we interpret histories, and that when a woman wants a new dress, what is new and ‘fashionable’, even in research, can sway a decision in what the seamstress creates. Through our actions, we in the community have given authority to these authors. The fact that some hold higher status as authors than others may have a lot to do with the status of the publication, the paper used in the printing, the institution that houses the collection studied, the use of colour, even the gloss used. When we look at the collections of garments studied themselves, are there photographs taken, or were artist’s drawings used? What was the quality and care given to the renderings? Are patterns included? Are they easy to use? Are the garments themselves stunning to the eye, or are they very plain-Jane? All of these considerations will make or break a fashion trend, or create authority for the author. And so, with each publication, copies of the fashions that were published appeared at re-enactment events across the Eastern Seaboard, whether they were appropriate for the interpretation or not.

In the intervening years, more and more research has been published. Members of the community have been actively working with museums and in academia, and the research and scholarship has grown stronger with each author. Through online communities, care has been taken to ensure that people are interpreting their historical figures with considerations of time, place, culture, religion, and political status. And yet, fashion trends continue.

When Neal Hurst’s Bachelor’s Honors thesis was published, Hurst was working in the men’s tailoring shop at Colonial Williamsburg. Entitled ‘Kind of Armour, being peculiar to America: The American Hunting Shirt’ (Hurst, 2013), the paper set off a flurry of men wanting to own hunting shirts. Were they appropriate to all walks of life? All areas of North America? These were important questions that needed to be reflected upon before having a seamstress or tailor create one for a given interpretation. Hurst’s authority on the subject is well earned though, as this was not a simple undergraduate thesis. Hurst has the academic and employment credentials to back up his research, and that paper was well documented and written. Even he will exclaim though, that this garment is not appropriate for everyone in the hobby, and he would cringe if it were to become a fashionable trend in the community.

Neal Hurst with Will Gore, both wearing versions of the Hunting Shirt

Neal Hurst with Will Gore, both wearing versions of the Hunting Shirt

With ladies wear, these trends can be even more drastic. The men in our community, for the most part, belong to military units that have fairly strict codes of dress. Uniforms can be researched and recreated to the year, month, even the battle. Women, because they are a civilian population, do not have such restrictions, and so follow fashionable trends a bit more closely. Fashion trends that are regularly brought to mind include items like silk bonnets, printed cotton jackets, stripes, silk gowns, and brightly coloured or printed gowns. When each of these items listed comes into fashion within the community, or comes around again as fashionable in the community, questions of authenticity follow. Who would have worn these items? How would they have been worn? Is that printed cotton originally a bed hanging (upholstery fabric), or was is the lining on the hem of a quilted petticoat? What class/culture would have worn that garment? And even, is that fabric appearing to be too 1980s instead of 1780s? Who first wears a new style has influence on how it will become a fashion trend. Do they have authority? Have they been published? Do they have name fame? These are all considerations when considering a fashion trend within the hobby. Recently, a young woman in New England has entered the hobby, and quickly developed a following. She was well turned out from her very first event. Jennifer Wilbur studied fashion photography at the Fashion Institute of Technology (academic word fame amoung fashion people). Her clothing and interpretation is well researched and thought out. She seeks out talented individuals to create her wardrobe, even spending top dollar for historically accurate shoes from the UK that many longtime community members are hard pressed to consider. Even though her wardrobe reflects that of a lower situational Loyalist woman on the march with the army, I suspect she too will create a fashion trend amoung women in the hobby. She is considered an ‘authentic’ or ‘progressive’ member of the community, names given to ‘fashionable’ young people in the organization that are pushing research and interpretation beyond the comfort levels of the older generation.

Jennifer Wilbur, Loyalist woman on the march: One of her first events

Jennifer Wilbur, Loyalist woman on the march: One of her first events

So as I embark on my own explorations in the fashion of the 18th century, I am considering my own authorship, my own authenticity, and my own word fame. Amoung my smaller provincial group, I have long been considered ‘progressive’ with regards to the clothing I create and wear. Will this name fame be carried over into the larger North American community? How will my own research hold up, to scrutiny and to time? I will have to consider carefully my reader. I will also have to consider the extant pieces I will chose to include in the published document, were they a fashion ‘trend’ of their time? An anomaly, or widely worn? What was the cultural, class, religious, and political ramifications behind the garment, if any? I will also have to consider how my research is published. Will I choose a high gloss paper, a hard cover or paper back, colour photographs or the original garments, or line drawings? How will all of this play a role in how authentic my research is viewed, and how enduring it will become? Will I have the authority to speak and be heard?

The Author: Kelly Arlene Grant

The Author: Kelly Arlene Grant

Works Cited

Burnston, S. A. (2000). Fitting and Proper. Scurlock Pub Co .

Foucault, M. (1980). What is an Author. In Lanuage, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Foucault, M. (1998). On the Ways of Writing History. In Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology. Essential Works of Foucault, 1954-1984 (pp. 279-96). New York: New Press.

Gilgun, B. (1993). Tidings from the Eighteenth Century. Scurlock Pub Co.

Hurst, N. (2013). Kind of Armour, being peculiar to America: The American Hunting Shirt. Williamsburg Virginia: College of William and Mary.

Linda Baumgarten, J. W. (1999). Costume Close Up: Clothing Construction and Pattern, 1750-1790. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Riley, M. (2002). Whatever Shall I Wear? A Guide to Assembling a Woman’s Basic 18th century Wardrobe. Graphics and Fine Arts Press.

The post Author and Authority: Creating Fashion Trends in Historical Re-enacting (Probe on Foucault’s ‘Author’) appeared first on &.

]]>The post Why doesn’t the Dalai Lama have an H-index? appeared first on &.

]]>This probe will investigate citation practices and contemplative knowledge through the framework of discourse as defined by Michel Foucault in On the Archaeology of the Sciences: Response to the Epistemology Circle.

Tenzin Gyatso is the fourteenth Dalai Lama and was recognized as the reincarnation of the thirteenth Dalai Lama at the age of two. The Dalai Lama is the spiritual leader of Tibet and is believed to be an enlightened Bodhisattva who has “postponed their own nirvana and chosen to take rebirth in order to serve humanity” (www.dalailama.com). Born in 1935, his monastic studies began at the age of six and by the age of twenty-three he passed his final examinations which earned him the equivalent of a doctorate in Buddhist philosophy. In addition to his work as the political and spiritual leader of Tibet he has received several honorary doctorates and published over a hundred books. Since the 1980s the Dalai Lama has collaborated with scientists and researchers in a variety of disciplines which has led to Buddhist philosophy informing modern scientific research and conversely modern science has been incorporated into the monastic curriculum at traditional Tibetan institutions.

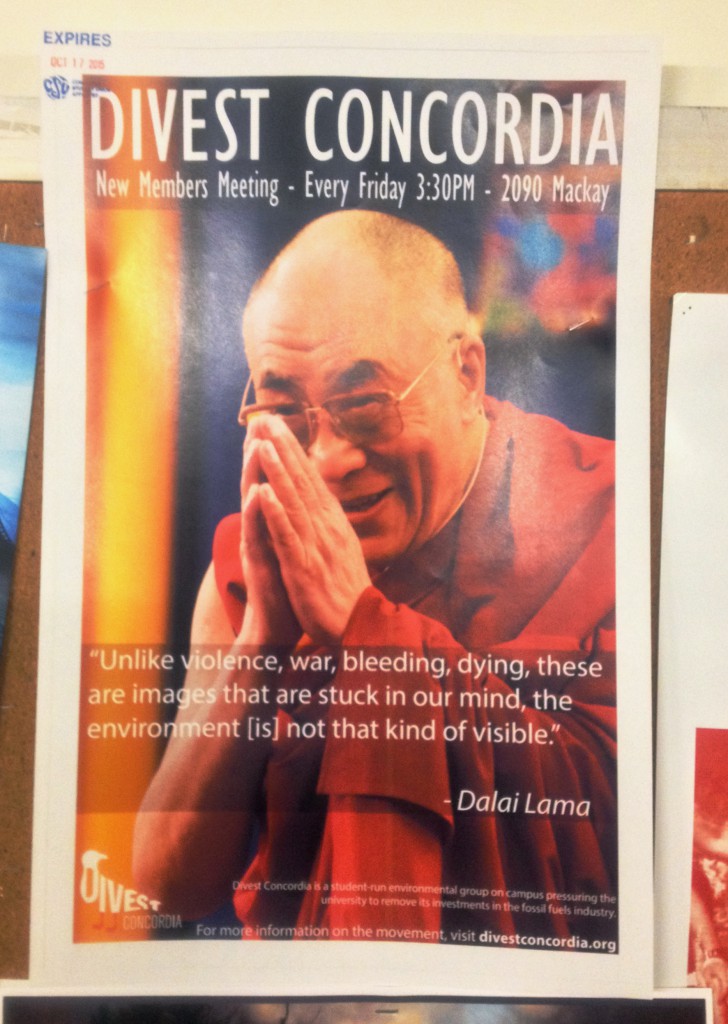

The H-index is a bibliometric tool used to indicate the productivity and impact of a researcher according to journal publications and citations. Named after Jorge E. Hirsch the H-index is commonly referenced in the valuation or ranking of scientists and scholars. A Google Scholar search on the Dalai Lama returns several results including his 1998 book The art of happiness: A handbook for living which has 413 citations. The top citation of this work is by Richard Layard, Professor Emeritus of the London School of Economics. His 2011 book entitled Happiness: Lessons from a new science is cited 4077 times. Apart from the irony of citing some of the oldest wisdom traditions in the context of a ‘new science,’ the citation system works well for Dr. Layard who has a respectable H-index of 69. Also telling is that ten times more authors cite a respected academic rather than a spiritual leader who has dedicated his life to the study of the subject. Why do we need “sophisticated, cutting-edge, scientific research” (Layard abstract) that will share the same conclusions as the knowledge that has survived from ancient texts? Does the practice of citation offer an opportunity to revisit and revalue older philosophies and practices?

Given that the Dalai Lama is widely cited amid everything from academic publications to motivational posters, how should his authority, authorship and knowledge be considered in relation to established methods of recognition within the scientific and academic community? I will examine this question in relation to Michel Foucault’s proposed methods of discourse analysis. This question also lends itself well to working through Foucault’s assertions on authorship and continuity within history since the Dalai Lama cannot easily be considered as an individual but rather as the representative of a cannon of knowledge and experience going back at least to the 14th century.†

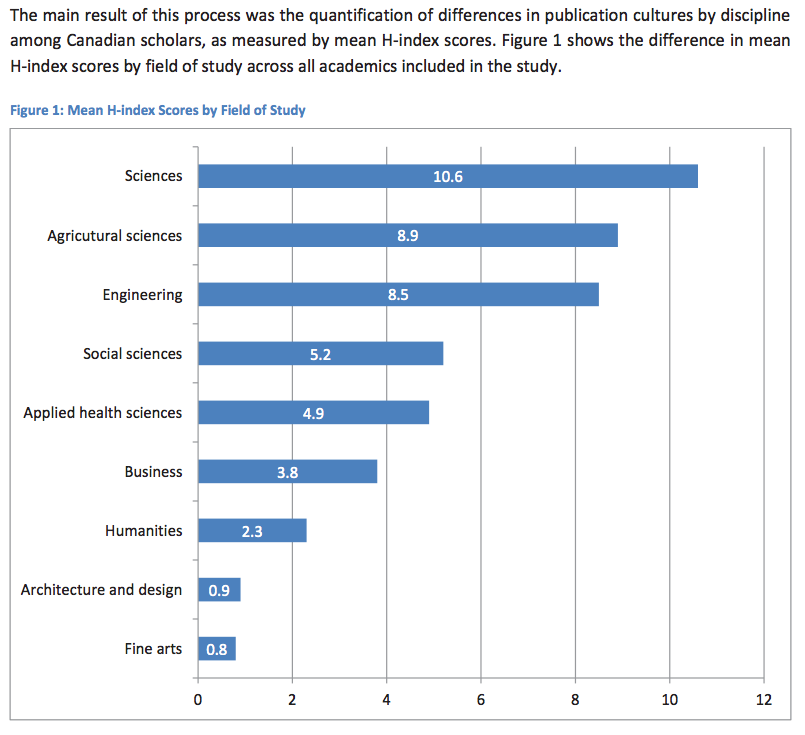

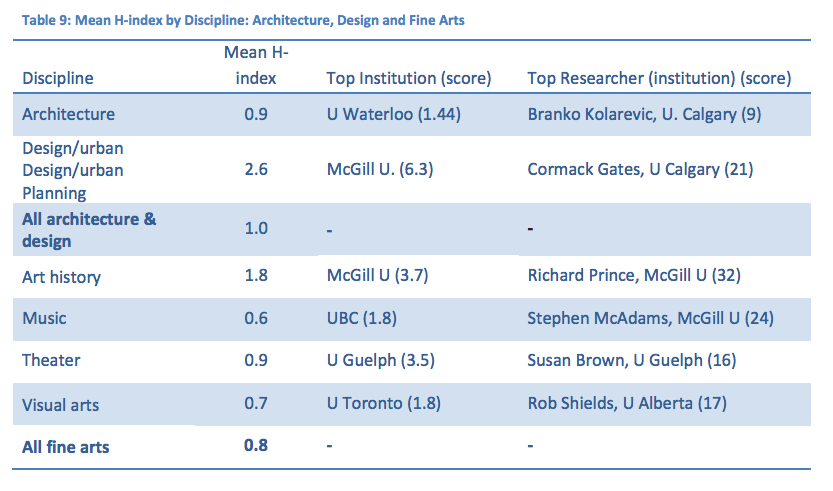

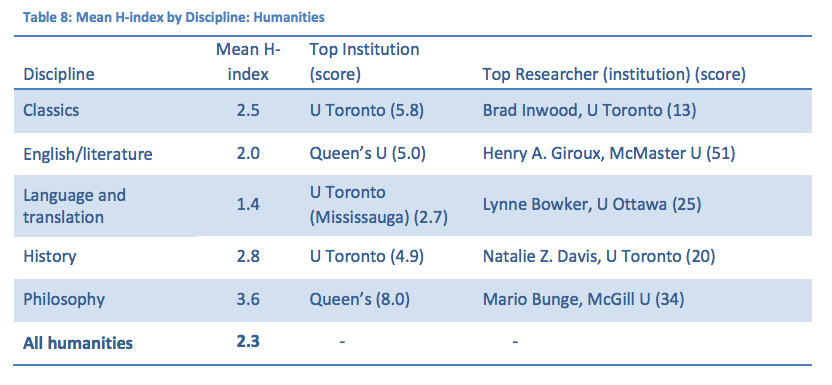

The H-index is considered to work best when applied to scholars within the same discipline since publication practices vary across fields of study. For example, the mean H-index in science is 10.6 compared to 2.3 in the humanities according to a 2012 study by the Higher Education Strategy Associates (HESA) comparing 71 Canadian institutions (Jarvey 15).

A number of criticisms have been raised concerning the methodology of the H-index but regardless it is quickly becoming the most common bibliometric indicator due to the increasing reliance on rankings evident today worldwide. One challenging problem with the H-index is how it favours those who remain strictly within their disciplinary boundaries. Impact is measured by number of citations, a narrow metric which should perhaps be considered as impact within the discipline because it means the most to those also within the field. What is the impact of the Dalai Lama’s work, or of works of fiction? The transcendence of impact in the social and cultural reality of the world make it nonsensical to attempt to give the Dalai Lama an H-index, but it also makes the H-index nonsensical in its own right.

If the validation of knowledge is done by others within the field (as is the case with peer-review) the “referent itself contains the law of the scientific object” (Foucault 331). The way in which knowledge is ascribed value within a field of study could be considered a constitutive part of that field. How should we value knowledge that emerges from a self-justifying system of production and validation? Foucault describes truth as “a system of ordered procedures for the production, regulation, distribution and operation of statements” and is inextricably linked to the systems of power that produce and sustain it (Hacking 35). I see this as the basis for Foucault’s assertion that “the thematic of understanding is tantamount to the denegation of knowledge.” (Foucault 332)

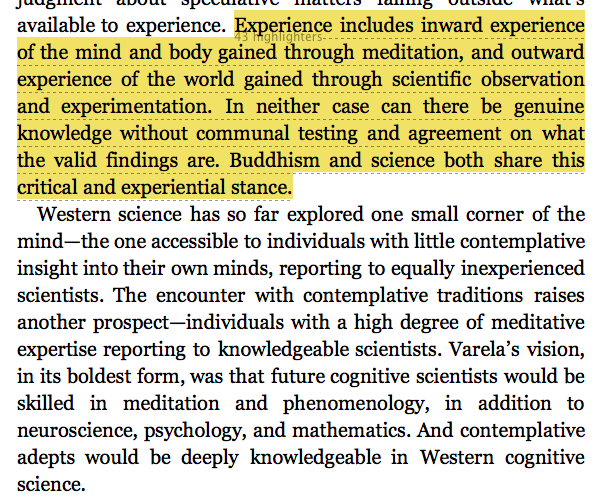

Foucault’s On the Archaeology of the Sciences: Response to the Epistemology Circle provides insight for thinking through these issues. Language is defined as “a system for possible statements” (Foucault 306) and is compared to discourse in relation to the finite or infinite possibilities of statements. Taking simply this description of language, it’s fruitful to consider the value of various works as pursuing the same goal or conveying the same content through different ‘languages’. For example, the Dalai Lama’s and Richard Layard’s books on happiness have similarities in content but are intended to reach different audiences through different means of validation and distribution. If we consider the object in common happiness, then the linguistic definition of happiness offers a limited conception of this entity that doesn’t account for its transformation and translation throughout time. Within Foucault’s discourse, we would instead consider the “law of distribution” through which the referent (happiness) can be understood (313). In this case happiness may refer to something quite different according to context but the unity of the references creates the unity for the referent to maintain some coherence. Ironically when describing the art of happiness, an alternate conception of happiness is precisely what both authors prescribe (to conceive of contentment instead).

In following Foucault’s circuitous logic I feel as though the meaning of a statement is lost early on in the journey. In many ways the path feels analogous to the stochastic Shannon-Weaver theory of information which values the ability to access data (and the probability of that data being found) above all other considerations, such as what the content (meaning) or context may be (Shannon). This theory arose in the context of data being transformed into binary signals regardless of whether the original source was auditory, visual, textual or any other signal that can (in the twentieth century) be translated into the same base code. Foucault’s archaeology highlights the non-disciplinarity of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and his theory of discourse attempts to similarly circumvent disciplinary limits in order to look exclusively at an individual utterance as a unique, autonomous entity. Even though he accepts that the statement is linked to the situation that gives rise to it, he asks that it be considered exclusive of this context. He instead wishes to examine the nature of the statement as “technical, practical, economic, social, political, or other variety” (Foucault 308) which just feels like another kind of classification.

Foucault describes the goal of discourse as attempting to determine why a different statement did not appear in the place of the one given. He wishes for each statement to be evaluated independently to determine why it was chosen in just the way it was. But often there is more than one way to express something, and there can be illogical, inexplicable factors determining what gets said. He is attempting to escape the false continuity that linear, teleological historical narratives generate but the nature of questioning already implies some sort of narrative. If perhaps the only fundamental assertion that can be made is “cogito ergo sum” (I think therefore I am) then a story is already unfolding, namely that I am present and I’ve existed long enough to formulate a question. Narrative is an inherent consequence of consciousness and is built into language even more so. What would the Dalai Lama be without his status as a reincarnated Bodhisattva? Is it even possible to describe Buddhist practices without making reference to the historical construction of the Buddhist philosophy?

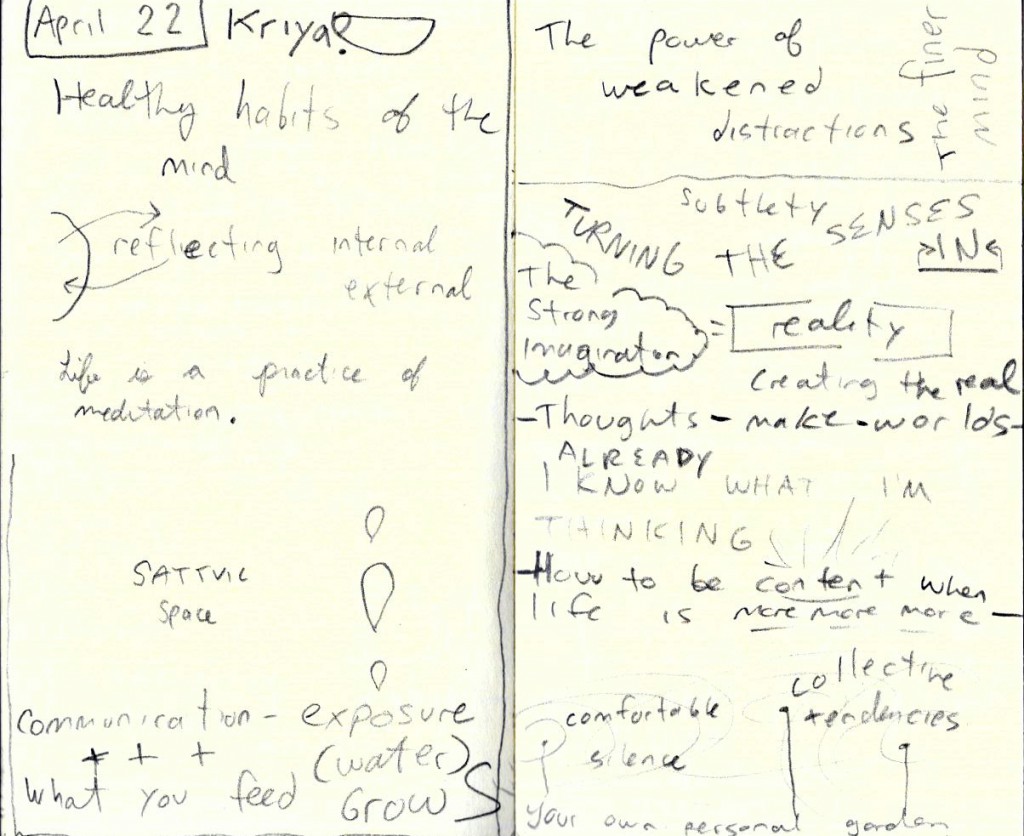

The exercise of trying to grasp and employ Foucault’s discourse analysis can be compared to a passage from Evan Thompson’s 2015 book Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self and Consciousness in Neurosience, Meditation, and Philosophy††. In Chapter 5, which describes neuroscientific sleep studies being conducted with lucid dreamers, he explains how an account of a dream is always given from outside of the dream (Thompson 164). From the moment of awakening there are already linguistic, temporal and cognitive laws shaping the conscious state from which the dream can be recalled and shared. Although Foucault exhausts a plethora of devices and algorithms for examining statements “a statement is always an event that neither language nor meaning can completely exhaust” (Foucault 308). Given this difficulty, perhaps there should be more room for what Foucault considers the problematic origin and narrative tradition he heartily wishes to discard. In one of his most poetic passages about ‘the nonsaid’ he describes discourse as putting into words that which is “already found articulated in the half silence which precedes it” which is then uncovered and rendered silent by its articulation (Foucault 306). This statement reminds me of a note I recorded at a satsang (meditation class) not long ago which was “you already know what you’re thinking”.

Personal page of reflections from April 22, 2015 Satsang at Sattva School of Yoga, Edmonton, Alberta.

This idea was prompted by the discussion about the non-silence that runs through the mind and must be set aside in meditative practice. This ‘narrative on auto-pilot’ can be exhausting if un-checked. The concept that it can reasonably be set aside because it is in fact a circular narrative telling me things I already know liberates me from the stories I tell myself. In this way meditative philosophy and Foucault have a common goal of escaping narrative habits and tendencies. Additionally many East Asian philosophical traditions including Buddhism teach non-attachment to the emotional values habitually ascribed to events. Hence, rather than seeing all things as positive or negative they should instead be taken with a more equanimous, balanced acceptance. Foucault’s project of removing the direct meaning of utterances sounds very familiar in this context.

I think there is value in finding a way to examine ‘enunciative events’ apart from their historical or linguistic ties but it feels counter intuitive to isolate them to the extreme proposed by Foucault. His writing style involves frequently guiding the reader down a path he intends to reveal as fallacious, creating mistrust in the reader that leads to a more critical reading of the text. This strategy could perhaps be employed in his goal of examining discourse. By enacting his philosophy rather than mainly describing it through negation (such as the request to reject traditional models of understanding) readers may follow his path and find themselves no longer needing to cling to traditional modes of understanding. For now I’ll hold onto the aspects of Foucault’s discourse that resonate true within my own systems of valuation, the statements in which he reaches for something beyond what can be described — the “voice as silent as a breath” (305-306).

Works Cited

Foucault, Michel. Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology. New York: The New Press. 1998. Print.

Hacking, Ian. Foucault: A Critical Reader. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. 1986. Print.

Jarvey, Paul, Alex Usher and Lori McElroy. Making Research Count: Analyzing Canadian Academic Publishing Cultures. Toronto: Higher Education Strategy Associates. 2012. Web. Link

Lama, Dalai. The Art of Happiness: A Handbook for Living. New York: Penguin. 2009. Print.

Layard, Richard. Happiness: Lessons from a new science. New York: Penguin, 2005. Print

“The Dalai Lamas.” His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet. The Office of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet. n.d. Web. 26 September 2015. Link

Shannon, Claude. E., and Warren Weaver. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. 1949. Print.

Thompson, Evan. Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self and Consciousness in Neurosience, Meditation, and Philosophy. New York: Columbia University Press. 2015. Print.

† From www.dalailama.com: “In 1447, Gedun Drupa founded the Tashi Lhunpo monastery in Shigatse, one of the biggest monastic Universities of the Gelugpa School. The First Dalai Lama, Gedun Drupa was a great person of immense scholarship, famous for combining study and practice, and wrote more than eight voluminous books on his insight into the Buddha’s teachings and philosophy. In 1474, at the age of eighty-four, he died while in meditation at Tashi Lhunpo monastery.”

†† Thompson does an exemplary job of bridging Eastern and Western philosophical traditions and both are strengthened through his explorations.

Additional images:

The post Why doesn’t the Dalai Lama have an H-index? appeared first on &.

]]>The post Farber meets Foucault: A Probe appeared first on &.

]]>Writing is now linked to sacrifice and to the sacrifice of life itself; it is a voluntary obliteration of the self that does not require representation in books because it takes place in the everyday existence of the writer. Where a work had the duty of creating immortality, it now attains the right to kill, to become the murderer of its author. [1] ~ Michel Foucault, Language, Counter-memory, Practice

Let’s assume for a moment that we the starting point is a stage play with one sole Author. In an adaptation or translation of that play, who is the Author? Now what happens if there are multiple texts that are woven together? Who then is the Author? Is it the goal of both Author and Adaptor to disappear? Or is it the goal of the Adaptor to reincarnate the Author in his or her own work? Does the “play” that exists in an adaptation or translation fracture the seemlessness of the meaning and intention of an Author? If so, what does it expose? Does it expose the infrastructure of the theatre? The infrastructure of culture? Does it force us to look at our contemporary cultural episteme? Are we faced with the inability to look away from our own assumptions?

Molora[2], created (or composed) by Yael Farber, is an adaptation of the Oresteia Trilogy placed in the context of post-Apartheid South Africa in the midst of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission proceedings. Klytemnestra, a white woman, has killed her husband Agammemnon. Her daughter, Elektra, steals her brother Orestes away from the house and takes him to a nearby village. The children are mixed race, but are portrayed by black actors. Elektra endures seventeen years of torture as her mother tries to pry the location of her son from her daughter’s lips. She will not give in. Orestes returns. Elektra and Orestes plot their revenge against their mother, but when the moment arrives, Orestes cannot go through with it. Elektra, with the help of the chorus of women (played by the Ngqoko Cultural Group), relents and breaks the cycle of vengeance, offering instead her hand to her fallen mother.

In this play, Farber uses draws together text from Aeschylus’ Agammemnon and The Libation Bearers (Choephoroi), Sophocles’ Electra, and Euripides’ Elektra. She incorporates Xhosa and split-tone singing of the Ngqoko Cultural Group, based out of the region of Transkei. She utilises elements of traditional African storytelling as well as the testimonial from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission trials and winds them together with characters and techniques from the Greeks. But why? What effect does this have on our understanding of the story, or of both stories? What do we see that we wouldn’t have otherwise noticed if this were a new play rather than an adaptation?

Let’s first look at the physical playing space.

(image from http://www.cornellcollege.edu/classical_studies/lit/cla364-1-2006/01groupone/Scenery.htm)

In the mise en scène, Farber says, “This work should never be played on a raised stage behind a proscenium arch… Contact with the audience must be immediate and dynamic, with the audience complicit – experiencing the story as witnesses or participants in the room, rather than as voyeurs excluded from yet looking in on the world of the story.”[3] While she employs the same set up of raked audience with a flat playing surface (complete with an altar) as the Greeks, her intentions are widely different. The Greek amphitheatres were designed to maximize the seating capacity through sightlines and acoustic sensibility and privilege the nobility by seating them closer to the playing space. Farber, on the other hand, believes that this stage set up will create a relationship between audience and actor (or story) that is complicit and active. The audience is no longer allowed to disappear into the darkness of the traditional Western theatre houses of the proscenium arch. They must bear witness to the story. Having used this play as a teaching tool for text analysis classes, I know that this notion of active audience can make people uncomfortable. Why? We are a society that thrives on witnessing. Through posts on Facebook, Tweets on Twitter, pictures on Instagram, (etc.) we demand that the world around us witness our lives through social media. It is almost as if that witnessing is a requirement of being, and without it, without the acknowledgment (likes, thumbs up, retweets, comments) we are nothing. It seems to be, using Foucault’s term, to be the foundation of our cultural episteme[4]. So what is it about this idea of witnessing in Farber’s play that seems so radical? It is live. We cannot be anonymous. We can’t hide behind our digital selves and pretend we are something we are not. Witnessing requires consent and voluntary exposure of self on both the part of the actor and the audience. It requires seeing. Perhaps in Farber’s play her purpose or intention was not related to disappearance, but rather to exposure.

Let’s see if this theory holds true in the language of the script and production. Farber uses text from four different Greek plays. In the text itself she uses footnotes to cite the passages and acknowledge their Author. In this respect, we cannot avoid noticing or acknowledging the Author of these stanzas. But for her own words, for the lines of dialogue that are solely her creation, there are no footnotes. She writes in both English and Xhosa and there are no footnotes for text in either language. By publicly announcing the presence of the former Authors, is she purposefully turning the attention away from herself? Is she trying to disappear into the spaces between their text? In a production, of course, there are no footnotes displayed as subtitles. So the barriers between Authors becomes more permeable. The classical Greek passages become one singular voice (the dead white man perhaps?). By contrast, Farber’s writing becomes more evident. The play begins with the line “Ho laphalal’igazi. [Blood has been split here.]”[5] The first words uttered on stage in Molora are in Xhosa, followed swiftly by a verbal translation in English (marked by the square brackets). This Translator is a character in the play and this pattern of Xhosa being translated into English exists throughout the play. But it only ever goes one way. Nothing is translated from English into Xhosa. When we hear the Xhosa speech, we are very aware that there is a different voice from the Greeks in play. What then is the role of the translation? What does it do? Is it merely a mechanism to ensure the audience understands the text? If so, why use Xhosa at all? Perhaps it is again about exposure. By including linguistic plurality in the play, Farber forces the audience to rely on the interpretation of the Translator (unless they are fluent in Xhosa, of course). We need to trust in the Translator to give us the correct story. This dependent relationship seems to speak to our willingness to so quickly accept a singular master narrative of history or of historical events. Farber is using two languages and three perspectives (Greek, English contemporary and Xhosa contemporary) to tell the story in Molora. And we, as audience members, are witnessing these three perspectives simultaneously. The use of Xhosa is more than just a mechanism linguistic understanding. It is exposing our lack of understanding, the gaps in our knowledge.

On her site, Yael Farber writes about Molora:

Our story begins with a handful of cremated remains that Orestes delivers to his mother’s door. From the ruins of Hiroshima, Baghdad, Palestine, Northern Ireland, Rwanda, Bosnia, the concentration camps of Europe and modern-day Manhattan – to the remains around the fire after the storytelling is done…

MOLORA [the Sesotho word for ‘ash’] is the truth we must all return to, regardless of what faith, race or clan we hail from. For when fire meets fire, it is only ash that will remain.[6]

Foucault wants the Author as individual to disappear from view into his or her own work. Farber, on the other hand, wants us to appear in our own truth and humanity. Both Foucault and Farber use the idea of ritual – sacrifice for Foucault and fire for Farber – as the means by which we can achieve this disappearance. It is interesting that ash has a double meaning: it is the remains of something that was and also has the potential to spark new life. Farber changes the ending of the original story, saving Klytemnestra and Elektra, breaking the cycle of revenge and robbing the Greek tragedy of its catharsis. By breaking the cycle Farber has exposed the Author, but in doing so she also exposed the Audience and the assumptions we make. If we are all exposed, does that mean we all disappear, or does it mean that we finally look at one another?

When Klytemnestra believes she is to be killed by her son, she says, “Nothing. Nothing is written.”[7]

Perhaps Farber stopped the killing, too. Perhaps her role as Adaptor was to save the Authors and, in turn, save herself.

~A. Bowie, PhD in Humanities Candidate

NOTES

[1] Michel Foucault. Language, Counter-memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews. Edited by Donald F. Bouchard, translated by Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon. New York: Cornell University Press, 1997. 117.

[2] Yael Farber. Molora. London: Oberon Books, 1999.

[3] Ibid, 19.

[4] Michel Foucault. The Archeology of Knowledge and The Discourse on Language. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972. 191-192. The concept is also discussed in one of the class readings – Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology: Volume 2 by Michel Foucault pages 298-301.

[5] Farber, 20.

[6] http://www.yfarber.com/molora/

[7] Farber, 82.

Featured image taken from www.yfarber.com/molora.

WORKS CITED

Farber, Yael. Molora. London: Oberon Books, 1999.

Foucault, Michel. The Archeology of Knowledge and The Discourse on Language. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972.