The post Deforming the Human Interface: Glitches, Orlan, and Interacting with Biodigital Mess appeared first on &.

]]>The quest for “universals of communication” ought to make us shudder

– Gilles Deleuze (qtd in Galloway and Thacker, 23)

What universally communicative method could provide a better survey of the “manifest image” of the human face than Facebook? A search through the expansive territories of “face” gleans a uniform notion of expression embodying the same flat network of photo albums and timelines: “this is my face,” “I am this face,” “my face was here…” But what are we becoming through interface? And who isn’t becoming like everyone else?

The face is typically regarded as the body’s centre of sense and expression. Biological definition contains this singular organism within the epidermis, its movements correlated with the operations of the brain and central nervous system. Meanwhile, documented in social media databases, the self-involved posts always link back to pics of a publicly verifiable face. “Human subjects thrive on network interaction (kin groups, clans, the social),” write Alexander R. Galloway and Eugene Thacker, and the trafficking of face that occurs on the internet does not convince us otherwise. “[Y]et the moments when the network takes over — in the mob or the swarm, in contagion or infection — are the moments that are most disorienting, the most threatening to the integrity of the human ego” (5).

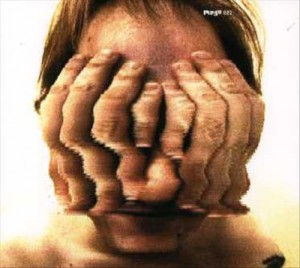

I receive a telephone call from a friend back in Saskatchewan… “Bad news,” they say. A neighbour’s face has been burned in a farming accident. Imagining the scarred flesh leads into networks and affiliations of other facial responses, their reactions to this news. It is perhaps most disturbing to consider a glitch in a familiar face; the face that becomes disfigured, the face that might be contagious infectious… Images of glitched faces provoke a unique array of “fellow-feelings” — ranging from compassion to disgust. These considerations need not be limited to horror films, but are both a biological and digital reality. This paper will consider something like this as its object:

Mathias Gmachl: GCTT CATT 2001

Of course, virtual and organic networks alike are always prone to these types of glitches. No matter how “flat” reality can appear when you have time to prepare for a selfie, a quick survey of the faces aboard the métro reveals varieties of countenances, all of which flourish with unique blend of gaps, dents, bruises, make-up and fissures. Whether it is through avoiding to meet their eyes in the street or if we follow them on twitter, we are in constant negotiation with “otherness.” But these interactions are not limited to “friends,” “colleagues,” and other Instagram users, but with the fields of outside “corruptive” entities, viruses and bugs that are enmeshed in our thriving social communities. And although many of these actants are invisible and undetectable, the right kind of glitch can threaten the unity, efficiency and function of assemblages. Galloway and Thacker aver that “this dissonance is most evident in network accidents or networks that appear to spiral out of control — Internet worms and disease epidemics, for instance” (5). But these exemplifications do not show a network that is in disrepair, but show one that “works too well” (6). For their function as well as their counter-functional disruptiveness, for their dangerous unpredictability and their interface-altering potentiality, glitches demand closer scrutiny. Perhaps Marina Galperina is correct to claim that “Glitch is the new selfie.” Here, for instance, are two more examples created via the app “glitché”:

Georg Fischer : Glitch Experiment

Dmitriy Krovtevich : Pixel Drifter

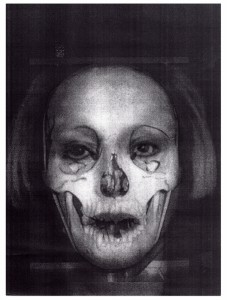

Galloway and Thacker ask how we might engage as both individual and social bodies, as parts of living networks involving “aggregates of singularities — both human and nonhuman — that are implicated in the network” all of which is “constantly undergoing changes” (70,71). Perhaps art provides response to these queries. In the “Glitch Studies Manifesto,” for instance, Rosa Menkman emphasizes the aesthetic beauty of such experimentations: “the glitch is a wonderful interruption that shifts an object away from its ordinary form and discourse, towards the ruins of destroyed meaning” (340). Performance art has a long history of exploring the glitchiness of the human form, using the body as an intimate interaction between technology, synthetic and organic material:

Exogene (1997)

from Precolombian Self-Hybridizations (1998)

African Self-Hybridization (2003)

Though Orlan has never professed to be a “glitch artist,” her facial metamorphoses embody some of Menkman’s principles of “glitch art”: as a “shifting, ungraspable, unrealized utopia connected to randomness and idyllic disintegrations” (341). Quoting from Orlan’s official website, the artworks are described as

self-portraiture in the classical sense, but realised through the possibility of technology. It swings between defiguration and refiguration. Its inscription in the flesh is a function of our age. The body has become a ‘modified ready-made’, no longer seen as the ideal it once represented; the body is not anymore this ideal ready-made it was satisfaying to sign.

With a mantra that embraces pain, transformation and suffering, Orlan’s performances require surgical, manipulative, deformative alterations of her face for each public appearance. Media innovations are utilized not as progressions toward facial perfection, but as noisy disturbances of typical body language, as defacements of the smoothed and structured systems that try to hold face.

from Omnipresence Surgery (1993)

from Omnipresence Surgery (1993)

Through all the multiplications, subfunctions, microfunctions of the interface between organic and electronic materials, the internet offers fertile ground for viewing such facial metamorphoses. Orlan’s facial repertoire hightlights the gaps and fissures that thrive within the human network; her face becomes through symbiogenesis — process of composition whereby new organisms are formed out of two or more separate structures. The face is characterized by the messiness from whence it emerges, from what John Law describes as “a reality out there and beyond ourselves” (5). Orlan is always beyond the self, cannot be fixed. Her face is a lack of identity, “that which is elsewhere. Absent” (7). To remix of Samuels and McGann’s philosophy of deformative poeisis, Orlan undergoes a constant change whereby the face (and not text) becomes a site of process. These acts deform the possibility of anticipating particularities, “short circuit[ing] the sign of [facial] transparency and reinstalls the [face]” (30). Orlan’s collaborations with surgeons and surgical instruments display how poeisis can assume new “physiques,” and are far more impressive than a backwards reading of Wallace Stevens. As facial constancy is glitched, we are forced to look in the eyes of the unfinished character of construction and infrastructure. Glitches thus complicate simplified concepts of the face, diverting methods toward interfacing with multiple forms of presence.

Operation Réussi (1991)

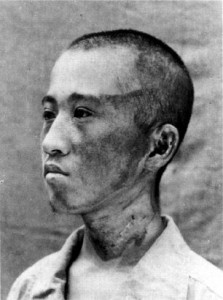

Orlan acts out the extremes of subjugating one’s physiognomy to the alterations, additions, divergences of the interface between medicine and art. We are caused to ponder what happens when the face “yields to such a remapping” until something “emerges as an imagination of something we do not know” (Samuels and McGann 38). The universals of communication are rewired through the symbiogenesis of artistic creation. But we are all subject to such constitutional glitches; indeed, the history of human faces is full of glitches. Lynn Margulis points out that human organisms are the result of “a long line of progenitors that can be traced back to the first bacteria” and these microbes continue to characterize who we are (qtd in Manning 91). “If it doesn’t kill you, glitch might help make you stronger!” But then, Walt Bogdanich’s essay on “The Radiation Boom” demonstrates that while new technology allows doctors to more accurately attack tumors and reduce certain mistakes, its complexity has created new avenues for error — through software flaws, faulty programming, poor safety procedures,” and a variety of other complications (166). Bogdanich reports 133 occasions where modulated radiation technology equipment was misused, occasionally glitches in the machinary accidentally administered fatal overdoses to hospital patients (168).

How are biotechnologies, electromagnetic waves, and digital uploadings altering notions of the human face? Does new media mean new faces? Eugene Thacker’s Biomedia “facilitates and establishes conditionalities, enables operativities,” to seek further to answer the question “what can a body do?” But we are also learning (sometimes via catastrophe) the limitations of biological and digital systemic operations. Both domains “inhere each other,” writes Thacker: the biological ‘informs’ the digital, just as the digital ‘corporealizes’ the biological” (7).Following John Law, however, we might regard “otherly mess” that is not easily incorporated into political, social, and philosophical analyses. Law elucidates the problems that result in the systemic othering of this so-called “mess,” those who are not easily incorporated into idyllic or smooth conceptions of human societies. Besides looking at glitchy art, how should we proceed through involving organic, synthetic and digital networks in order to address the symbiogenetic antagonisms of glitch? There can be serious ethical implications in disavowing the messiness that results in the fall-out of glitches. Perhaps these faces (which can be viewed at hiroshima-remembered.com) provide some clues as to why it is crucial that we try to “make sense of the mess.”

Out-there is certainly more of a mess than we can put a face to, and we certainly need to envisage (much) better methods of drawing attention to the gaps, abnormalities and exceptions that warrant critical attention. As our bodies interface with the rest, we inevitably share many of the same microbes, germs, DNA, and other detritus that flows in, out and through. A glitched notion of the human face demands new conceptions of realities which are neither coherent nor fixed, but highlights that we are part of the shifting collaborations and antagonisms that occur via biodigital interactivity. And as Law points out, we must become more cognizant of the “out-hereness as well as in-hereness” of such a reality. Network analysis thus necessitates also reckoning with the worms, bugs, and viruses that threaten the structure’s stability. Out-there/in-here glitch is not only poeisis — the creative randomness emerging out an error in digital circuitry — but a destructive and revisionary critique of infrastructures. Glitches certainly demand a broad reconsideration of face (of interface, of facing up), and may even move toward novel, more radical decisions to look courageously at the multiplicities and diversities that are thriving “out-there” as well as “in-here.”

Works Cited

Bogdanich, Walt. “The Radiation Boom.” Glitch: The Hidden Impact of Faulty Software. Ed. Jeff Popows. Montreal: Prentice Hall, 2011. 165-185. Print.

Fischer, Georg. “Glitch Experiment.” Fast Company. Mansuento Ventures, 19 Sept. 2014. Web. 19 Nov. 2014.

Galloway, Alexander R. and Eugene Thacker. The Exploit: A Theory of Networks. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007. Print.

Galperina, Marina. “Glitch is the New Selfie.” Fast Company. Mansuento Ventures, 19 Sept. 2014. Web. 19 Nov. 2014.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered. AJ Software and Multimedia, 2013. Web. 19 November 2014.

Krovtevich, Dmitriy. “Pixel Drifter.” Fast Company. Mansuento Ventures, 19 Sept. 2014. Web. 19 Nov. 2014.

Law, John. “Making a Mess with Method.” After Method. 3 (2003): 1-12. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Manning, Erin. Politics of Touch: Sense, Movement, Sovereignty. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007. Print.

Menkman, Rosa. “Glitch Studies Manifesto.” Vortex II (2008):336-347. Web. 10 Oct. 2014.

Orlan Official Website. NetAgence, 2014. Web. 16 Nov. 2014.

Samuels, Lisa and Jerome McGann. “Deformance and Interpretation.” New Literary History. 30.1 (1999): 25-56. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

Thacker, Eugene. Biomedia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004. Print.

The post Deforming the Human Interface: Glitches, Orlan, and Interacting with Biodigital Mess appeared first on &.

]]>The post Boot camp: “Glitch studies is what you can just get away with” appeared first on &.

]]>This boot camp has been fucked up from almost the very beginning, and I point to the originary temporality from the start of this assignment to mark the very late juncture of this boot camp submission: let’s consider tardiness the primary fuck up of this boot camp, one which strives, as McGann and Samuels argue, to “break beyond conceptual analysis into the kinds of knowledge involved in performative operations” (25). Thus my boot camp, while perhaps analytical, is also inextricably linked with its performance of the tardy, and by academic standards, the flawed status the assignment and my overall class grade officially receives; my boot camp is not done, and myConcordia grades remain “incomplete” by institutional standards, where the “INC” can also indicate an aborted “incorrect,” the institution’s designation of my scholarship trajectory defined by missing deadlines, but moreover a failure to adhere to the “critical orthodoxy” with which McGann and Samuels believe deformance engages. Here “myConcordia” makes the system’s critical orthodoxy obvious; linking student, professor and postsecondary institution, myConcordia filters students’ academic experiences through an electronic system network, into which your data and student status is plugged and oriented based on algorithmic input. So just as “[d]eformative moves reinvestigate the terms in which critical commentary will be undertaken” (McGann and Samuels 35), I also wish to reinvestigate the terms under which critical commentary (i.e., academic grading and submission) participates and endorses in postsecondary institutional orientations (by virtue of posting this boot camp, I am requesting a rupture in the official academic structure).

For if Rosa Menkment is correct in her assertion that “[i]n [glitch] theory, noise has been isolated to the different occasions in which the static, linear notion of transmitting information is interrupted” (339), then my boot camp, the late object that attempts to filter informational noise (or Law’s mess, to return to class readings), disrupts the stable, linear notion of transmitting information via the proper, designated channels (submit somewhere by sometime), ultimately requiring the university and course professor’s technological amendment post-term, forcing an “acknowledge[ment] that the computer [and a postsecondary institution’s database] is a closed assemblage based on a geneaology of conventions, while at the same time the computer is actually a machine that can be bent or used in many different ways” (340): just like the glitch, my boot camp necessitates an awareness of conventions and how they construct and close off systems from alternative potential (semesters, end of term deadlines, final papers, boot camps, assignments in general), while also necessitating a reorganization, a “generative or redefining” and hopefully “positive” amendment to my grades based on a softening of the hard deadline (Menkmen 340). Students’ requests for extensions from professors illustrate this tension between the geneaology of conventions and their “bended” uses, and so in some respects my boot camp is predictable and obvious, but my boot camp performs and interrogates these conventions by making them the subject matter of the assignment itself, and indeed producing the assignment through a deformance of the assignment.

And yet, this “deformance” is in fact a “performance,” as truly “fucking things up” through deformance would more closely align this assignment in the “incomplete” rather than “completed, tardy” status. Thus as I reach the end of my “deformance”-cum-“performance,” my hope is that this boot camp will actually raise my grade, rather than provide a more deformative critique of the system of grading itself; this boot camp, like the glitch, begins by dismantling the form of a sanctioned system by refusing to submit to/within its standards (here I use Menkman’s term with intent, and ignore the dynamic of a glitch that has accidentally arisen), but this destabilization ultimately ends: “once it is named [or capitalized upon, its use(s) exploited], the momentum – the glitch – is gone… and in front of my eyes suddenly a new form has emerged” (Menkmen 341). So my “deformance” results in a “performance” of academic thought, inculcated within a social order and its “critical orthodoxies” of actually handing an assignment in and adhering to expected writing rules, rather than saying “I fucked this one up” and giving up. If my boot camp begins by explaining that I have indeed “fucked things up,” the rest of the assignment is dedicated to correcting the fuck-up, to ensuring that I place myself back into academic discourse, suppressing the (non-)creative conditions of my boot camp (its absence come the due date) and hoping to forget the transitory, glitched moment in favour of ratifying the (previously absent) object through and by the system instead of truly deforming it, illustrating how “glitch studies is a misplaced truth; it is a vision that destroys itself by its own choice of and for oblivion. The best ideas are dangerous because they generate awareness. Glitch studies is what you can just get away with” (345).

Works Cited

Menkman, Rosa. “Glitch Studies Manifesto.” Video Vortex Reader II: Moving Images Beyond YouTube. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011. 336-47

Samuels, Lisa, and Jerome McGann. “Deformance and Interpretation.” New Literary History 30.1 (1999): 25–56.

The post Boot camp: “Glitch studies is what you can just get away with” appeared first on &.

]]>The post The Poetry of Patch Notes appeared first on &.

]]>In one of her later essays, Eve Sedgwick (2012) muses ‘sometimes I think the books that affect us most are… the books we know about – from their titles, from reading reviews, or hearing people talk about them – but haven’t, over a period of time, actually read’ (123). Unread, these books can remain ‘objects of speculation, of accumulated reverie’ (ibid.), proving enduringly provocative or inspirational even if what we extrapolate from them is wrong. Sedgwick’s observation, of course, does not apply solely to books – one might, for example, imagine ‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue’ to be addressed to a person who’s just overcome some kind of dire tribulation, rather than someone with no options left; Sedgwick herself made hay with the fact that her essay ‘Jane Austen and the Masturbating Girl’ was held up as an exemplar of all that was wrong with literary study not just before its critics had read it but before it had even been written (1994, 15).

As for books, films, songs and essays, so for games: video game titles can be both evocative and deceptive, all the more so because even when we know what a game looks like it is hard to determine how it will feel until the controller is in our hands. Personally, I have always been highly susceptible to the allure of Japanese games with so-called “Engrish” titles – Bulk Slash; Virtual On: Oratorio Tangram; Omega Boost. As Trevor Harrison (2008) argues, “Engrish” is characterized by constructions that might seem bizarre or just comically wrong to the native English speaker, but which are, in many cases, governed by an ‘internal logic’ based on creating unaccustomed and even outright paradoxical syntactical combinations productive of a certain connotative frisson (144-6). Prioritizing feeling, novelty and impact over straightforward sense, this strategy is a good fit for the kinds of visceral spectacle in which the games named above trade.

It is not just games’ titles that speak to us, for this is an industry in which developers and publishers often have recourse to buzz terms, bullet points and neologisms in order to convey how their product works and just what distinguishes it from its rivals. From Shenmue’s ‘quick time events’ to Red Faction‘s ‘Geomod technology’ to Forza 5’s ‘drivatars’ and Battlefield 4’s ‘levolution’ system, video games are in love with unwieldy coinages. A staple of back-of-the-box feature lists, such terms are easily ridiculed, but we might productively see them as constituting an understudied microgenre of game-writing – commercially motivated to be sure, but also a key means of ‘paratextual’ mediation between developer and potential player (Genette, 1997).

Try as they might to entice us, however, such terms ultimately tend to be too vague, not to mention too empty, to truly tantalize. Fortunately there is another kind of gamic paratext that, while tailored to a different (in fact, an almost almost diametrically opposite) purpose, often proves more adept at piquing playerly curiosity: patch notes. Insofar as they list the problems that a particular software update will attempt to fix, cataloguing flaws, conflicts and oversights, these texts should provide a sobering counterpoint to the heady claims made by feature lists. In practice, however ironically, they often afford us intriguing insights into the nature of a game’s operation and appeal.

Skyrim (which title, we might note in passing, wags have suggested better befits a toilet cleaner than a fantasy role-playing game) provides a helpful case in point. The game was released on the eleventh of November 2011 in what was, even for the famously bug-prone Bethesda Softworks, a formidably glitchy state: dragons flew backwards; corpses arbitrarily dematerialized; monsters’ skeletons became lodged in solid walls. By the end of the month the game had been patched to version 1.2, and the patch notes that accompanied this update have since come to be regarded as something of a classic of the genre, exemplifying the power of such texts to synecdochically gesture at the complexities, the forms of emergent spectacle, the proliferating possibilities that made the game so engaging in the first place. Moreover, as Kenneth Goldsmith (2011) would no doubt point out, you only have to remove one line to make the list into an albeit rather unconventional sonnet:

UPDATE 1.2 NOTES (all platforms unless specified)

Improved occasional performance issues resulting from long term play (PlayStation 3)

Fixed issue where textures would not properly upgrade when installed to drive (Xbox 360)

Fixed crash on startup when audio is set to sample rate other than 44100Hz (PC)

Fixed issue where projectiles did not properly fade away

Fixed occasional issue where a guest would arrive to the player’s wedding dead

Dragon corpses now clean up properly

Fixed rare issue where dragons would not attack

Fixed rare NPC sleeping animation bug

Fixed rare issue with dead corpses being cleared up prematurely

Skeleton Key will now work properly if player has no lockpicks in their inventory

Fixed rare issue with renaming enchanted weapons and armor

Fixed rare issue with dragons not properly giving souls after death

ESC button can now be used to exit menus (PC)

Fixed occasional mouse sensitivity issues (PC)

General functionality fixes related to remapping buttons and controls (PC)

Most commentators immediately seized upon the line about dead wedding guests, a teasingly terse clause that might have been custom-engineered to elicit awe, amusement and curiosity. While I had already sunk a good number of hours into the game by the time this text was disseminated, I was not, prior to reading these notes, even aware that it was possible to get married in Skyrim, and was still less able to imagine how the scenario of a corpse arriving at my avatar’s wedding would actually play out (would they be upright? Would there still be flesh on their bones? What differentiated a dead Nord from a living one?). If Bethesda had done an admirable job of hyping the game prior to release (harping particularly on the importance of the ‘radiant storytelling’ system that would generate a literally endless supply of quests) the scenario sketched in this one line arguably gives a much clearer sense of what makes Skyrim special than any developer interview or press release could – indeed, one wonders just how many players, upon reading the notes, purposefully avoided downloading the update in favour of booting up the game and going a-wooing.

I should perhaps make it clear at this point that by drawing attention to patch notes I am not attempting to prop up the by now rather tired argument that glitches have the potential to somehow cut through gaming’s illusionistic patina, putting us in touch with something more ‘real’. Instead, I want to suggest that in the patch note we might find inklings of a mode of writing capable of doing justice to gaming’s virtual dimension (in the properly probabilistic sense), of capturing the way in which players can simultaneously (or almost simultaneously) experience games as captivating fictions, technical achievements and bug-ridden pains in the neck. The rest of the list, while devoid of any single item quite so compelling as the dead guest clause, is interesting and instructive in other respects, and does much to suggest the multifaceted nature of both games and gameplay. Particularly noteworthy are its tellingly coy circumlocutions (PS3 performance issues are not fixed but ‘improved’; Bethesda would struggle to get this version of the game stable over an extended series of updates spanning several months) and its bracingly abrupt switches in register, from metaphysical considerations in one line to banal technical minutiae the next (“Fixed rare issue with dragons not properly giving souls after death /ESC button can now be used to exit menus (PC)”). In this last respect the document resonates with Ian Bogost’s (2012) comments on the list as an ‘ontographic’ technology, a mode whereby a ‘particular configuration [may be] celebrated simply on the basis of its existence’ (38). For Bogost, lists, which are functional first and foremost, offer a salutary corrective to more ‘literary’ modes of description, enjoining attention to specific details, to the fact that ‘no matter how fluidly a system may operate’ it will depend to some degree on the (often uneasy) collaboration of elements that remain, on a fundamental level, ‘utterly isolated [from one another], mutual aliens’ (ibid. 40). In Skyrim’s case we can see how the interoperation of different features and protocols within the game system supported an experience that some found captivating, others ‘broken’ and far from fluid.

As we might imagine, what is true of professional commercial products is also true of mods, with the important difference that the barrier to entry is lower than with full retail games: with no need to pay, owners of the original game have little reason not to download an add-on and see for themselves whether it lives up to the claims made in its maker’s blurb. Skyrim has a particularly active mod scene, one in which the cut-throat competition for downloads and upvotes has bred a discourse rife with inflated promises, unwieldy acronyms (W.A.T.E.R. = Water and Terrain Enhancement Redux), and much loose usage of the term immersive. Again, however, descriptions of bugs and glitches tend to paint a picture that is at once more reflective of the actual experience on offer and more capable of supporting speculation, fantasy and projection. It is not uncommon for modders to admit that they have no idea why users are experiencing particular problems, and such admissions – which are, in some cases, very detailed and frank – offer glimpses into the logical guts of the game that can be as dizzying as any polygonal vista. I leave you with some snatches from modder Araanlm’s notes on his Here There be Monsters mod, notes I find both cryptic and strangely romantic: “Somehow in doing this I managed to mess up the original location of Jormungandr, which was just north of Northwatch Keep. I moved him to a different island north of Orphan’s Tear, but the original location is still messed up and causes a crash to desktop… I’m not sure if the monsters can actually use [summoning spells] since they are not human NPCs.”

Araanlm (2013). Here There be Monsters. Steam Workshop. http://steamcommunity.com/sharedfiles/filedetails/?id=81166964

Betheda Blog (2011, November 30). Skyrim 1.2 Update. http://www.bethblog.com/2011/11/30/skyrim-1-2-update/

Bogost, Ian (2012). Alien Phenomenology, or, What its like to be a Thing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Genette, Gerard (1997). Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goldsmith, Kenneth (2011). Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age. New York: Columbia University Press.

Harrison, Trevor (2008). 21st Century Japan: Anew Sun Rising. London: Black Rose Books.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky (1994). Tendencies. Durham NC: Duke University Press

– (2012). The Weather in Proust. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

The post The Poetry of Patch Notes appeared first on &.

]]>The post Disruptive Mods and Skyrim appeared first on &.

]]>As part of the IMMERSe research I’m currently involved in, our team has been spending time lately examining mods for the Bethesda Elder Scrolls game Skyrim. Mods are (generally) user generated content for commercially produced and distributed games, and can alter anything from the realism of how light reflects off of surfaces in the game to building whole new environments for players to explore and missions for players to complete. Our primary focus has been on immersive, narrative mods that significantly effect the story aspects of the game, but one particular point of interest I’ve developed over the last couple months has been when mods fail, or at least appear to fail in their intended, stated goal. In the interest of seeing what happens when mods break themselves, break each other, or break gameplay, I enlisted some colleagues and went about trying to see how we could use mods to fuck up Skyrim.

It wasn’t hard to screw up our Skyrim play. We used a very simple methodology–throw a whole bunch of mods on the game at once and see what happens. We installed and ran multiple aesthetic mods: dozens of patches designed to add richer textures, more realistic dust in the air, detailed sound effects, and so on. Also installed were large narrative mods like the Falskaar pack (which gives a player an additional 25 hours of playable missions and adds a new map to the game about a third of the size of Skyrim itself) and other interactive mods that alter the way the player interfaces with the environment. The hope in running all these mods at once is that one mod gets in the way of another in a really interesting way, and that the player consequently gets a chance to learn about how the game functions or see it from a new perspective (another hope might be that all these mods just overload the computer’s brain, but we were playing on a really powerful machine). As I said, this wasn’t hard to achieve. Turning on the Falskaar map and mission pack, we set about to try some new adventures, but some of the survival mods we’d installed got in the way of us going about our business. Survival mods effect your ability to deal with the elements, so swimming is a bad idea–your stamina will fall away, your vision will blur, and eventually bone chill will set in. Unfortunately, all the traditional ways to warm yourself up and dry yourself off have been disabled by some other mod, so you’re at a loss for what to do. We eventually found an indoor fire that built our player’s stamina, but by then we’d wasted about twenty minutes. Meanwhile, our cold weather mod was giving all of the Falskaar NPCs frostbite. We decided to head back to Skyrim proper before anyone died of exposure.

An effect of our Cold and Wet mod in Falskaar. This woman is not supposed to look like this.

One of the problems with using so many mods at once was that is was sometimes hard to tell which mods were glitching. One audio mod forces the player to turn her head in order to hear any dialogue (though effects, music, and ambient sounds are always audible). The strange algorithmic logic of such a mod–ears are on the side of the head and necessary for hearing, so obviously you want to point your ears toward the source of sound–are reminiscent of some of the AAA games of the last decade, where turning or walking away from the source of sound turned the volume on it way down. However, larger immersive Skyrim mods such as Falskaar also include dialogue recorded by amateur voice actors, often in their homes or some other locale lacking the benefit of soundproofing. The final result is that the player turns her head to hear dialogue from a barmaid who sounds like an American teenager doing a bad British accent with a dishwasher running in the background. These sounds aren’t so much non-diegetic as they are acousmatic–it’s impossible to tell just where the sounds are coming from, or if they’re meant to be in the world or not, a question raised by the fact that the player’s modded character is apparently hard of hearing when it comes to human voices.

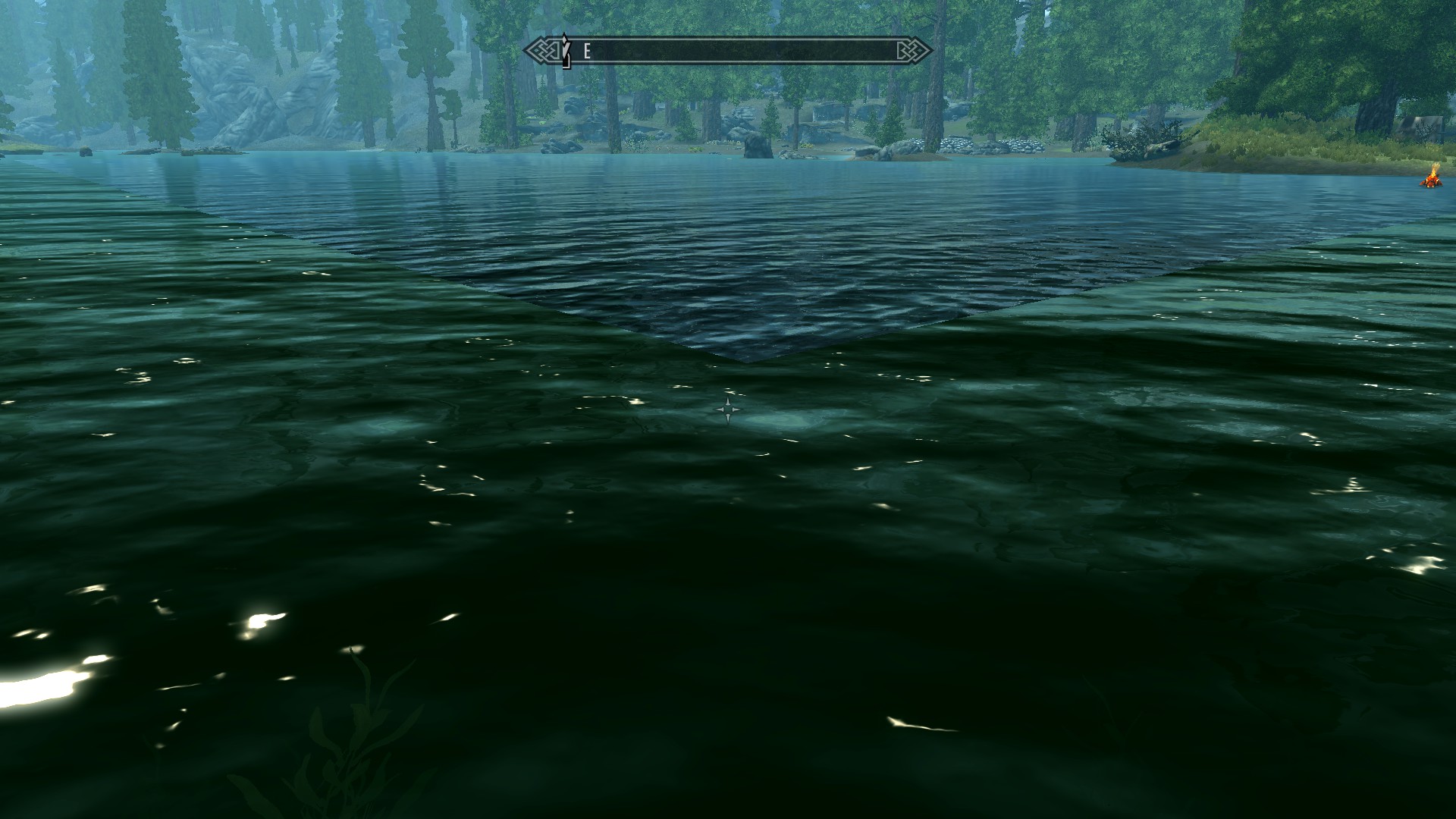

Then there were the mods that changed the look of the environment. Now these were interesting. I had hoped that by running multiple mods designed to affect the same game elements, we might get to see a total breakdown of the game’s visual interface processes. We ran two water mods at the same time, and I hoped that when we approached a lake we would observe a pixelated flickering mess as the two mods fought for control over what the player saw. Instead, they just cooperated and cut the lake right in half. Sections of the water were green, others were blue, and the areas were separated by nice clean lines and right angles. Even underwater a flick to the right would change the opaqueness and tinting of the view, while up above an invisible boundary marked the difference between ebb and flow and the waters rippled in opposite directions. Meanwhile, multiple tree mods had an easy time getting along too–some would exist in the same space (making for interesting topiary arrangements), while others were sometimes pushed up out of the ground–not to fall over, but rather to float overhead, suspended in the air.

Two waters mods getting along swimmingly, while my flaming horse (also a mod) paddles through with undampened spirits.

Water mods just a bit to the left or right.

While some multiply-modded trees glitched out visually…

While some multiply-modded trees glitched out visually…

…others were altered spacially.

…others were altered spacially.

These kinds of mod glitches shed new light on the software processes of the game. Rather than seizing up or prioritizing one mod over the other, the system has opted to resolve the conflict in what it thinks of as an equitable fashion. While we generally think of a game as incapable of breaking its own rules, Skyrim here has dealt with an informational surplus by simply incorporating all options. At least, that’s how it works out visually.

The explicitly iterated point of almost all of these mods is to create a richer immersive fictional environment for players. What’s unstated in this equation is that they are also there as the material evidence of the training process of mod creation–modders make their art not only because they saw something lacking in the environmental effects of the game, but also to see if improvements could be made, as a way to pass the time, for the “egoboo” that comes with anonymous or pseudonymous online achievements, or just for fun. This is all besides the point: what they invariably claim to be doing is enriching gameplay through software manipulation. In the event of a mod glitch, then, we might want to say that the modder has failed: where they say they want to make the game world more immersive and absorbing, what their mods have actually done is disrupt. Certainly there’s nothing so distracting to the experience of gameplay as pixels jarringly out of place or overly detailed texture lag slowing play down to a crawl. Even when two mods sit alongside each other more or less harmoniously, the player is taken out of the game to think about the non-diegetic aspects of the game.

I want to suggest here that this is exactly the strength of the mod glitch. Here “playing” the game can be replaced by “playing with” the game, and immersive exploration becomes about acutely noticing the points of fascination in the game world rather than using the mods to be able to pretend the environment is real enough to be seamless. Why should our experience of games strive at realism? Why do we go so far out of our way to make most of what constitutes the game (hardware, software, programming) invisible?

At the very least, these glitches reinforce a kind of hermeneutics of suspicion about the game. The slippages represented by these glitching mods can function pleasurably in much the same way as a film’s continuity errors or diegesis-breaking production “goofs.” Just as bits of film trivia are known only by and kept only for cinephiles, these mod overloads are passed around and enjoyed by lovers of Skyrim–only those players who enjoy the game enough to build, seek out, or use mods for the game will bear witness to these technological failures or mistakes.

The post Disruptive Mods and Skyrim appeared first on &.

]]>The post Google Translate: Glitch Art and Deformance Methods appeared first on &.

]]>Probe * Nov 21st

“Dominate the dream of freedom due to the translation, materialized, reduce A normative struggle, new analysis focuses on what we call the transfiguration seems Emerging. This could significantly change the way through the public decision-making Close to the regime of recognition. No one claimed that schools have been decisively This concept covers the terrain. Even if we see the development of scholars, it is doubtful analysis protocols circulation and transfiguration understanding Replace the meaning and translation tools to understand they are doing Or so. However, the entire work, could not be more different in style, tone, Content and discipline, we see the development of new technologies catch Mapping function, not meaning as foreground figure Public culture technology Public Forms Coordination and figurating machine, the main component is not Situated in the play signifier and signified but functional indexicality Imitation (iconicity)…”

– Gaonkar & Povinelli Technologies of Public Forms: Circulation, Transfiguration, Recognition. Translated with Google Translate, 394[i]

Just when I was about to enter high school, my home state of Minnesota began one of the state’s first Chinese language programs. I jumped at the chance. While French and Spanish were great options, they had nothing to do with my personal history; Chinese was a way, I thought, to actualize a classic teenage yearning to ‘get in touch with my roots’. Turns out it was torture.

As many of you probably know, written Chinese is a non-phonetic pictographic system which means you have to straight up MEMORIZE four-thousand characters to be literate. Each character has anywhere from one to thirty-six strokes. EACH. As soon as I left high school and the pressure of grades to keep me absorbing and retaining, I promptly forgot everything. Everything, that is, except how to speak.

Fast forward a decade or so and I find my work has landed me back in China for the long haul. My spoken Chinese has picked up over the years but I’m still relatively illiterate. And as the use of cell phones and texting/chatting rises in China – even amongst my old masters – I’ve had to rely on a host of translation software to help me. The best (free) one so far is Google Translate.

I’d usually send a text to a master using Google Translate and when he wrote back, I’d ask a friend to read the Chinese out loud to me. Sometimes there were obvious miscommunications, but nothing we couldn’t solve with an actual phone call. It wasn’t until I started translating their texts and emails into English that I felt a sudden horrific awareness of the software’s limitations. I had been blindly putting my faith into this program to do the most important thing for me: communicate.

What?

And, what?

If that’s what computer translation had done to their words, what had I been saying to them?

Of course, somewhere in the back of our heads aren’t we all aware that translation isn’t perfect? Even the most bilingual translators in the world can’t produce an exact duplicate of meaning simply because languages aren’t just a sets of parallel words; it represents so many other possible differences such as culture, societal norms, emotional realities, histories, geography, political systems, ideologies, religions, etc. And even if we’re working in the same language, how can we ever be sure that what we say is what is exactly perceived on the other end? We can’t, because translation is so often a one-way street. Then why was I so shocked at my masters’ mangled texts?

For this week’s readings on glitch and deformance studies, I’ve chosen to fuck up/with Google Translate. To be sure, I’m not the only one who has been burned by the seductive promise of free translation. An estimated 200 million people are using Google Translate around the world every day[ii]. Do they know about Google Translate’s inherent incapabilities? Do they trust it blindly as I once did? Are they aware but still, like me, using it because of practical and financial reasons? What does this reliance on translation software mean in a greater context? It may mean that everyday, 200 million messages are being communicated incorrectly.

In Google Translate’s informational video, they explain how their translating program works:

Instead of trying to teach our computers all the rules of a language, we let our computers discover the rules for themselves. They do this by analyzing millions and millions of documents that have already been translated by analyzing millions and millions of documents that have already been translated by human translators. These translated texts come from books, organizations like the UN and websites from all around the world. Our computers scan these texts looking for statistically significant patterns – that is to say, patterns between the translation and the original text that are unlikely to occur by chance. Once the computer finds a pattern, it can use this pattern to translate similar texts in the future. When you repeat this process billions of times you end up with billions of patterns and one very smart computer program.

To me, this method exposes a host of issues, which the video does touch on but very very briefly. The ‘frequency of documents’ and therefore the quality of the translation depends on a number of variables; not just the preponderance of the language in question but language pairs as well. If the United States and China are trading more documents than say, Lithuania, then English to Mandarin translation will most likely fair better than English to Lithuanian. And, what kinds of documents are these? If many of them come from the UN as explained in the video, what kind of language patterns are most frequently found? What kind of language patterns are not found? How can we, the user, know what it does better or worse? How do we expose this system of its breakdowns and our expectations of perfection?

In Menkman’s manifesto on Glitch studies and Glitch art, she describes the glitch as having “no solid form or state through time; it is often perceived as an unexpected and abnormal modus operandi, a break from (one of) the many flows (of expectations) within a technological system”. (Menkman 341) The glitch is what exposes our unconscious expectation of a system: Neo’s déjà vu in The Matrix. I like that Menkman doesn’t see this as a negative thing entirely, but a catalyst for creation. “A negative feeling makes place for an intimate, personal experience of a machine (or program), a system exhibiting its formations, inner workings and flaws. As a holistic celebration rather than a particular perfection these ruins reveal a new opportunity to me, a spark of creative energy that indicates that something new is about to be created.”(341)

Jerome J. McGann and Lisa Samuels suggest a similar method to glitch art, but apply it to literary studies and call it Deformance. They argue that, “most ‘antithetical’ reading models operate in the same orbit as the critical practices they seek to revise: when critics and scholars offer to ‘read’, or reread, a poem, they hold out the promise of an interpretation.” (McGann & Samuels 2) Instead, they suggest subverting our methods of close reading and even anti-close reading by moving past interpretation altogether. They do this in the performative realm and suggest Emily Dickenson’s ‘reading backwards’ as a starting point. It’s a way to get us out of our ruts and into estrangement. It’s glitch theory as a theory. Instead of just reading my transfigured paragraph as a way to defamiliarize and expose our implicit trust of a system, they probably would have urged me to then analyze this new deformance as a work unto itself.

Mark Sample, however, has no desire to merge the performative and the deformed. Instead, he encourages us to leave it there, mangled, transfigured and deformed. He doesn’t “want to put Humpty Dumpty back together again.” And while he cites deformance as a move in the right direction, he believes the theory is actually just another derivative of our habitual ‘searching for meaning’ because, ultimately, it circles back to the original text or creation of meaning. In Sample’s deformed Humanities, “the deformed work is the end, not the means to an end.” Perhaps he’d like that initial nonsensical paragraph by Gaonkar and Povinelli the way it is.

So how do we glitch it? Fuck with it? Deform it and let it stay that way? Break the flow and disrupt our expectations? Well, we could do worse than to start here:

The Fresh Prince: Google Translated (Personal Fave)

Strange Pattern Glitches in the Program

As this week wore on and I began playing with Google Translate, experimenting on the quality of translation for certain languages and certain passages from different types of texts, it also became clear to me that perhaps Google Translate is a form of ‘reading backwards’ or deformance. There is a beauty in the estrangement with which we encounter our language again and can bring us new insights or understandings not only about the text but about language.

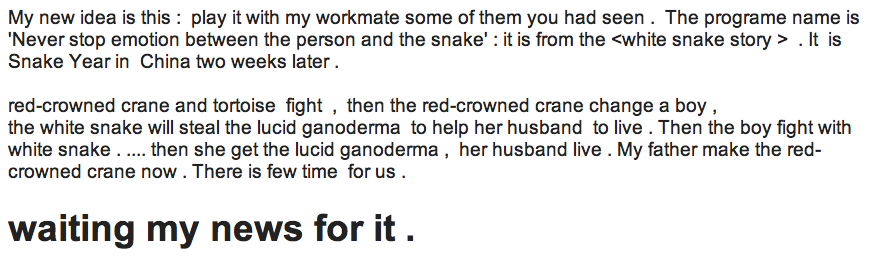

Take this ebook for example: 10 Poems Ruthlessly Mangled by Google Translate. The book simply takes ten poems and shows them in various states of transfiguration; one, two and three times through the translator. The intro states “some of the garbled poems are better then the originals. I don’t know how to feel about that.” (2) Or transfigured twice, “Good poetry twisted some more Original. I do not know how you feel about it.”

Selections from the ebook:

To me, all of these glitch art pieces and deformances do exactly what glitch studies promises. We are yanked into awareness by the hilarity, the unintended uses, the glitches. There is a beauty in the breakdown. To me, the most beautiful realization these methods and deformances show us is not only the fragility of a system, but of language, transfiguration and communication itself. We are our own imperfect translation computers impossibly slinging miscommunications everyday.

“Just as Foucault states that there can be no reason without madness, Gumbrecht wrote that order does not exist without chaos, and Virilio stated that technological progression cannot exist without its inherent accident. I am of the opinion that flow cannot be understood without interruption, or functioning without ‘glitching’. This is why we need glitch studies.” (Menkman, 344)

[i] Gaonkar, Dilip Parameshwar , and Elizabeth A. Povinelli. “Technologies of Public Forms: Circulation, Transfiguration, Recognition.” Public Culture 15.3 (2003):394

[ii] http://news.cnet.com/8301-1023_3-57585143-93/google-translate-now-serves-200-million-people-daily/

References:

Gaonkar, Dilip Parameshwar , and Elizabeth A. Povinelli. “Technologies of Public Forms: Circulation, Transfiguration, Recognition.” Public Culture 15.3 (2003): 385-397. Print.

Menkman, Rosa. “Glitch Studies Manifesto” Video Vortex reader II: moving images beyond YouTube. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011. Print.

Shankland, Stephen. “Google Translate Now Serves 200 Million People Daily.” CNET. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Nov. 2013. <http://news.cnet.com/8301-1023_3-57585143-93/google-translate-now-serves-200-million-people-daily/>.

Sample, Mark. “Notes Towards A Deformed Humanities” SAMPLE REALITY. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Nov. 2013. <http://www.samplereality.com/2012/05/02/notes-towards-a-deformed-humanities/>.

“Informational Video.” Inside Google Translate Google. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Nov. 2013. <http://translate.google.ca/about/>.

The post Google Translate: Glitch Art and Deformance Methods appeared first on &.

]]>The post game art, glitch, psychogeography. appeared first on &.

]]>I’m still finding myself in the liminal state between the end of my MA and the beginning of my PHD. The defense date for my MA thesis has finally been determined (Sept 23rd), where I’ll return to Toronto, defend and then come back to Montreal. While I’m prepping for my defense (rereading my thesis a couple of times a week, going over my literature, etc), I’m also prepping for my first year of course work at the PhD Level.

I’ve finally figured out my course work for the year, which has been challenging due to being a student in the INDI program. Without any required courses or parent discipline, I often found myself unable to register for certain courses because of the fact that several were mandatory for other programs. Thankfully though, that it done, and I find myself with two games studies courses, a course on media history and historiography, and a directed reading on psychogeography and peripatetics in literature. I’m excited for the year for several reasons, one of which has to be the fact that even though my MA was technically focused on game studies, that I have not taken a single course on the subject. The media history course is exciting due to my MA thesis work in alternate historical narratives centred on digital gaming platforms. Finally this directed reading will start my research into the historical traditions of psychogeographical practices in literature, which is part of the foundation I need to move forward with my PhD research linking these practices with those found in digital games.

Meeting with Andre Furlani, the English professor I’ll be doing my directed reading with, was a great experience. We discussed what I knew about psychogeographic literature, how I thought of its relationships with games, and my specific interest in its intersection with digital architectures and ludic cartography. It was one of those meetings where we were both so energized by the conversation, that we (at least I) didn’t really want it to end.

With the usual beginning of the year tasks out of the way, I’ve turned my attention to something to settling into the city, getting out and exploring, and visiting as many galleries as I can. One of the most exciting exhibitions I discovered was a Cory Arcangel retrospective currently on display at DHC ART in old Montreal. The show spans the work from his career, from video pieces, game hacks, sculpture, image, etc. Having a particular preoccupation with game art, I was eager to see what the exhibition had on offer.

The exhibition featured Arcangel’s ROMhack of the Nintendo game Hogan’s Alley, now called I Shot Andy Warhol. Displayed on an original NES with the Zapper (lightgun) accessory, gallery visitors could play the game on an old CRT television. In this game you must “Shoot Only Andys” and not the other pop culture icons that Arcangel has included in the game: The Pope, Colonel Sanders, and Public Enemy’s Flava Flav. It’s a fun, cheeky piece about celebrity culture and worship. Compounded by the fact that the piece is off in it’s own small space, feeling like a secluded confessional box.

Self Playing N64: NBA Courtside 2, is an interesting piece that combines automation, games and failure in an interesting way. Using a custom circuit board to modify a Nintendo 64 controller, Arcangel created a system for automated gameplay, removing the player from the equation. This modified system plays the game NBA Courtside 2‘s free throw mini game, featuring Shaquile O’Neil attempting to land a shot in the basket. However instead of creating a form of automation that would see successive shots landed, the system was designed to ensure a missed shot every time. The mini game is looped on itself, with the sounds of a basketball hitting the floor rhythmically, filling the room in the gallery. The idea of the automating failure is a common theme in Arcangel’s work, as he tends to create works which often bend and break the digital media that he is using in his artwork. Here’s a 7sec video I took of the piece (7sec is like Vine, but with a whole extra second of footage!)

The final game related work that was on display at the exhibition was Super Mario Clouds, which is, perhaps, Arcangel’s most famous work. A ROMhack of the original Super Mario Bros. for the NES, SMClouds removes all elements from the game, except for the clouds in the game, which then languidly move across the screen. By subtracting all of the other elements, SMClouds poses interesting questions on the nature of the medium of games and states of play. The game is no longer played but it rather played back, much more like a film or video. It highlights the underlying structures of ludic conditions within a game by removing them outright. While the piece itself is still one of my favourites, I have to say that I am disappointed by the installation at DHC. I have seen images of other SMClouds installations, and the DHC install seems, underwhelming by comparison.

Here is an image of the piece being shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York:

And here are photos I snapped of the installation at DHC:

While I feel like I understand what curator John Zeppetelli was trying to accomplish here, I feel that it lacks any real aesthetic that does justice to this piece. I get that placing it above the line of sight of visitors that the install asks us to look skyward, much like we would do if looking at real clouds. However, I look at this and can’t help but think of televisions installed in classrooms, large hulking beasts bolted to the walls for so-called security. I feel like it distracts from the piece, rather than highlighting it.

————————————————————–

Other than gallery hopping (this week I plan on going to the Contemporary Art Museum, and the Canadian Centre for Architecture), I’m reading Peter’s Ackroyd’s London Under, a fascinating recantation of the city that exists under the city. I’ve also begun getting back into creative production. Working on a new maquette for a large scale sculpture project which relates to the creation side of my dissertation work, as well as getting back into some digital manipulations such as game circuit bending and cartridge pulling. Here’s a sample of what my bending endeavours have gleaned so far.

Otherwise, excited and raring to go for coursework, and getting back into the swing of things, academically speaking.

The post game art, glitch, psychogeography. appeared first on &.

]]>