The post Environmental Humanities: Engaging Critics in an Interdisciplinary Space appeared first on &.

]]>Studies of the environment have a history of being characterized by a deep division between scientific research and humanities scholarship. In the same way, literary ecocriticism has been engrained within a critical lineage associated with an American wilderness ethic and Jeffersonian logic of “culture” in opposition to “the environment.” In conversation with anti-making discourses, that Debbie Chachra uses in her article for The Atlantic “Why I Am Not a Maker,” this probe will consider the interdisciplinary space set up in environmental studies—where the “real” is never far from “theories”—to discuss an academic journal that has privileged an integration of humanities research methods in environment studies that is decentering, destabilizing and enriching the field.

In the most recent issue of Environmental Humanities, a journal that publishes interdisciplinary research on the environment, scholars from across the disciplines were invited to respond to An Ecomodernist Manifesto (2015), a recently published article that argues for “decoupling human development from environmental impacts” (7). Characterized by the journal’s editors as “one of the more concrete and explicit statements to have emerged out of a broader effort to reconfigure what counts as environmentalism in the early decades of the 21st century,” the Manifesto generated a variety of responses from humanities scholars. Among them, figured Bruno Latour, who, in “Fifty Shades of Green,” compares the manifesto’s message to the invention of the electronic cigarette to say that the Manifesto might have found a way to “be modern and ecological without either of the two” (220). Far from a non sequitur, Latour uses the association to discuss “ecomodernism” as a concept, to challenge the manifesto’s claims within a sociological framework.

Everyone of you here who knows anything about controversies regarding human and non-human entities entangled together are fully aware that there is not one single case where it is useful to make the distinction between what is “natural” and what “is not natural.” [. . .] “Nature” isolated from its twin sister “culture” is a phantom of Western anthropology. What we are dealing with instead are distributions of agencies in which we are all entangled in ways which are highly controversial and the reactions to which are almost always highly counterintuitive. Or to put it in my language, the world is not made of “matters of fact” but rather “matters of concern.” “Nature is but a name for excess.” (Latour 221)

Latour’s integration of actor-network theory into a discussion of environmentalism to challenge “matters of fact” cuts to the heart of the project of Environmental Humanities: to provide a discursive space that “draws humanities disciplines into conversation with each other, and with the natural and social sciences” and allow discussion to move beyond the entrenched dualism of science and humanities research that has pervaded environment studies (Rose et al. 2). In the introduction to the journal’s inaugural issue, “Thinking Through the Environment, Unsettling the Humanities,” the editors describe the publication as a project with two aspects:

[. . .], on the one hand, the common focus of the humanities on critique and an ‘unsettling’ of dominant narratives, and on the other, the dire need for all peoples to be constructively involved in helping to shape better possibilities in these dark times. The environmental humanities is necessarily, therefore, an effort to inhabit a difficult space of simultaneous critique and action. (Rose et al. 3)

This articulation of Environmental Humanities, as a “space of simultaneous critique and action,” interpellates discourses of critical making. In his discussion of critical making as a conceptual and material process, Matt Ratto describes a practice that bridges “a deeper disconnect between conceptual understandings of technology and our material experiences with them” (253).

The use of the term critical making to describe our work signals a desire to theoretically and pragmatically connect two modes of engagement with the world that are often held separate—critical thinking, typically understood as conceptually and linguistically based, and physical “making,” goal-based material work. (Ratto 253)

In the same way, the contributors of Environmental Humanities reconcile a disciplinary disconnect between science and the humanities through an impetus to be relevant to contemporary environmental concerns. Like the collaborative space that Ratto describes, the journal’s emphasis on publishing scholarship intended for an interdisciplinary audience (written outside of established sub-fields of Environmental Humanities like environmental history or environmental philosophy) provides a space that “encourages the development of a collective frame while allowing disciplinary and epistemic differences to be both highlighted and hopefully overcome” (Ratto 253). However, the comparison between critical making and environmental humanities relies on equating the work of humanities scholars with that of the developers and designers from which Ratto derives his ideas. Which begs the question—

What do the humanists—as educators, critics and theorists—bring to the table?

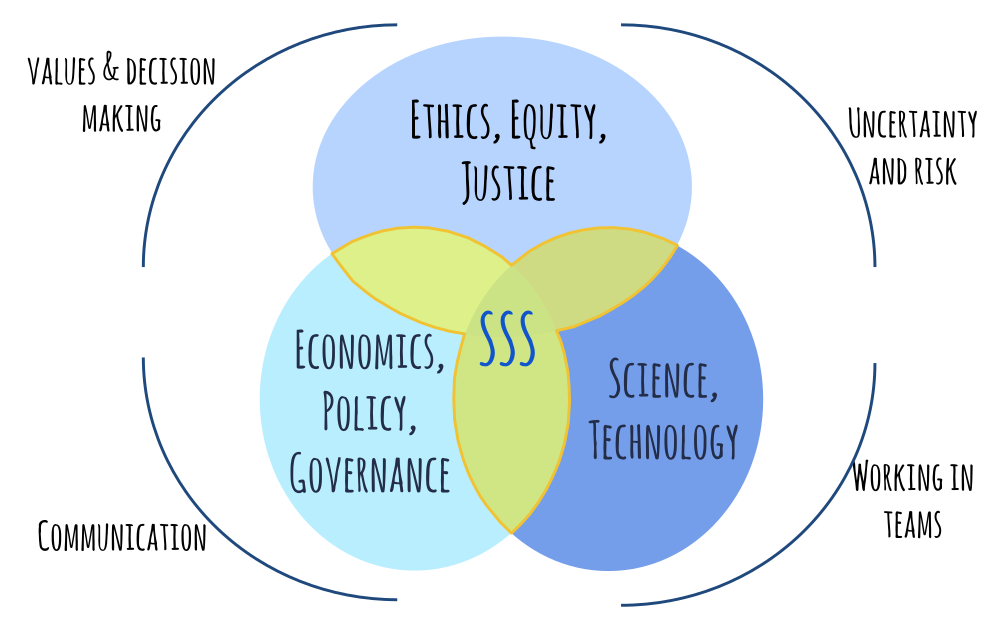

This graph, taken from the McGill University’s Sustainability, Science and Society program page—an interdisciplinary and interfaculty degree program that allows students to work in both science and the humanities—demonstrates they articulate as the three pillars of an interdisciplinary approach to studying the environment: science and technology; economics, policy and governance; and ethics, equity and justice. In a program designed to educate students in both current scientific research and critical discourse so they can affect environmental policy, this degree program seems to perform the “active” aspect of Environmental Humanities’ project: “to be constructively involved in helping to shape better possibilities in these dark times” (Rose et al. 3). Or, be relevant.

But if relevancy were the only driving force of research in the Humanities, Literature departments would be much smaller and devote their funding towards teaching Language and Composition, rather than give classes on old media, theories of happiness and a handful of postcolonial novelists that (almost) no one has ever heard of.

The primacy of relevancy in our society that privileges “making” and “producing” objects is a mind-set that characterizes the humanities, and their work in environment studies, “as a ‘non-science’, with the primary role of mediating between the natural sciences and ‘the public’. [. . .] at the core of these approaches is an impoverished and narrow conceptualisation of human agency, social and cultural formation, social change and the entangled relations between human and non-human worlds” (Rose et al. 2). However, the scholarship that the journal promotes is not based on interdisciplinary studies as an amalgamation of disciplines. In the same way that Latour challenges An Ecomodernist Manifesto’s understanding of “modern” and “environment,” interdisciplinary publications like Environmental Humanities challenge our understanding of the “humanities” by providing a space for scholars to circumvent the limitations of disciplinary approaches and perceived notions of the environment. Beyond an amalgamation of various disciplinary practices, interdisciplinarity in this case enriches critical thinking on the environment:

The humanities have traditionally worked with questions of meaning, value, ethics, justice and the politics of knowledge production. In bringing these questions into environmental domains, we are able to articulate a ‘thicker’ notion of humanity, one that rejects reductionist accounts of self-contained, rational, decision making subjects. Rather, the environmental humanities positions us as participants in lively ecologies of meaning and value, entangled within rich patterns of cultural and historical diversity that shape who we are and the ways in which we are able to ‘become with’ others. At the core of this approach is a focus on the underlying cultural and philosophical frameworks that are entangled with the ways in which diverse human cultures have made themselves at home in a more than human world. (Rose et al. 2)

The value in this type of thinking is that it isn’t entrenched in a single field or publication. Certain areas of study are emerging within established fields, like postcolonial ecocriticism in literary studies, that challenge our understanding of the interactions between humans and the non-human world. In the case of postcolonial ecocriticism, postcolonial theory is being used to revitalize and diversify ecocriticism’s traditionally American literary canon through the study of the treatment of the environment in texts written in the Global South, to give “environmental literary studies an international dimension” (Nixon 239). Decentering the study of environmental themes in literature allows postcolonial theorists to call into question “the perception that environmentalism is chiefly a politics that protects urban social privilege” (DeLoughrey 26).

One of the key themes of postcolonial ecocriticism is the use of imagination to articulate alternate relationships to the non-human world. In her essay on Amitav Ghosh’s novel The Hungry Tide, Laura White discusses Ghosh’s use of the novel form to develop “a rhythmic pattern of organization that reflects nonvisual ways of knowing the Sunderbans and that positions the novel as an alternative way of knowing which disrupts colonial and neocolonial visions of the Sunderbans by narrating interactions between geohistorically located and embodied knowers” (514-15). For Ghosh, only the broad form of the novel can “create ways of imagining human-nature relations and new ways of making environmental decisions” (517). In “The Greater Common Good,” a political essay published in 1999 on the human cost of monumental water development projects in India, novelist Arundhati Roy questions the “narrative of national development” that portrays infrastructure development as central to the nation’s interest, even as development creates developmental refugees that are “unimagined” from the nation’s “imagined community” (Nixon “Unimagined Communities” 150). In these texts, “imagination” (narrative, representation and subjectivity) is used to constitute place-based engagements with the non-human world, and “complicate” dominant ways of knowing and understanding the environment.

This approach to thinking about the border between the human and the non-human, through postcolonial literature’s engagement with environment, is only made possible in a space where literary scholars are in conversation with sociologists, anthropologists, environmental scientists and all the other actors involved in ecocriticism. In the same way that critical making, as a mode of exploration and articulation, allowed students at the Umea Institute of Design to develop ideas (Ratto 254), the interplay and exchange of ideas and critical perspectives between theorists of different disciplines studying the environment has allowed for alternate configurations of the border between human and non-human, cultures and environments, to be articulated. In the case of Environmental Humanities, this exchange was made possible within an interdisciplinary space that understood the critical value of Humanities research in its own right.

Cover Image: Taken from the cover of Environmental Humanities 7, which is available for you to read here. Image by Glendon Rolston “Spiderwebs Everwhere”.

Works Cited

Asafu-Adjaye, John et al. An Ecomodernist Manifesto. www.ecomodernism.org, April 2015. Web. 20 Nov. 2015.

Chachra, Debbie. “Why I Am Not a Maker.” The Atlantic. Web. Accessed 24. Nov 2015.

DeLoughrey, Elizabeth and George B. Handley. “Introduction: Towards an Aesthetics of the Earth.” Postcolonial Ecologies: Literatures of the Environment. London: Oxford UP, 2011.

Latour, Bruno. “Fifty Shades of Green.” Environmental Humanities 7 (2015): pp. 219-225.

McGill University. “What Knowledge and Skills Are Needed for Solving Sustainability Challenges?” <www.mcgill.ca/sss/> Web. Accessed 25. Nov 2015.

Nixon, Rob. “Environmentalism and Postcolonialism.” Postcolonial Studies and Beyond. Durham, N.C.: Duke UP, 2005.

Nixon, Rob. “Unimagined Communities: Megadams, Monumental Modernity and Developmental Refugees.” Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Boston: Harvard UP, 2011.

Ratto, Matt. “Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Social Life.” The Information Society: An International Journal 27.4 (2011): pp. 252-260.

Rose, Deborah Bird et al. “Thinking Through the Environment, Unsettling the Humanities.” Environmental Humanities 1 (2012): pp. 1-5.

Roy, Arundhati. “The Greater Common Good.” The Cost of Living. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 1999.

White, Laura. “Novel Visions: Seeing the Sunderbans through Amitav Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide.” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 20 (2013): pp. 513-531.

The post Environmental Humanities: Engaging Critics in an Interdisciplinary Space appeared first on &.

]]>The post Café Utopia appeared first on &.

]]>The coffee shop in question is the Brûlerie St-Denis on rue Masson (recently styled “La Promenade Masson”). This pleasant, gentrified Rosemont neighbourhood is known for its population of young families and aging hipsters pushed out of Mile End and the Plateau by exorbitant property values. The café is known for nothing in particular. The food is crap, and so is the coffee. If the word “utopia” applies to it, it is only in the literal Greek sense—i.e., “nowhere.” It is worth mentioning here only because it’s where I happened to write the first paragraph of this probe.

Inspired by Latour’s Laboratory Life, I’m observing the spaces in which the kind of knowledge I produce—little studies of literary works, analyses I support by ransacking the work of knowledge producers in a wide variety of fields—gets produced. As a participant in the production of this kind of knowledge and a frequent patron of cafés, I cannot claim to approach my subject, as Latour does, from a position of “anthropological strangeness” (40). I can, however, remember a time when cafés seemed strange and exotic to me.

I grew up on the outskirts of a small town where the only public establishments suited to daytime loitering were the tavern and the roadhouse. To me, cafés were fictional places where men wore berets and recited poetry (activities portrayed in American movies and TV shows as both unmanly and somehow subversive). When I moved to Montreal, I discovered that the true appeal of coffeehouses was their status as zones of public sociability. People went to relax, read, people-watch, meet friends, exchange opinions, expand their social circle. Some came to work, but this work usually consisted of taking long-hand notes in a ratty journal.

Coffee shops have changed since 1994. For one thing, there seem to be a lot more of them.

And a lot more people (myself included) now go to coffee shops alone, with no intention or desire to engage in any social exchanges beyond the transaction at the service counter which legitimizes, for an indeterminate length of time, their right to plop their laptop on any table they choose. They are there to work, and they’d appreciate your keeping the noise down at the next table, thank you.

Feeling a bit peckish, I’ve relocated to Café Lézard, a much superior café with better food and more attractive people than the Brûlerie. It’s retained some status as a cool local gathering place, however, and is thus probably less conducive to my work.

The development of mobile computing and the proliferation of free wi-fi enabled this transformation of the coffeehouse into a sort of communal office space. I choose to work in these spaces because they are outside of my home, where my family places constant demands on my attention, and yet nearby in case I am needed. The noise and movement of the space are dynamic enough to stave off boredom but not enough to seriously distract me. The bustle may even enhance creativity, a phenomenon that has inspired at least one silly app. Above all, there is a sense of being visible in a public space, which compels me to keep my fingers moving over the keyboard.

When we are alone in a public place, we have a fear of “having no purpose”. If we are in a public place and it looks like that we have no business there, it may not seem socially appropriate . . . so coffee-shop patrons deploy different methods to look “busy”. Being disengaged is our big social fear, especially in public spaces, and people try to cover their “being there” with an acceptable visible activity. (Gupta 49)

All of those people who claim premium tables so they can hunch over their laptops all afternoon have good reasons for doing so, and yet it’s possible that I mildly resented them before I became one of them. They seem to break an implied agreement by entering a social space and refusing to socialize.

But what if we expand our conventional understanding of the social to include our laptops and tablets, the coffee shop’s router and ISP, and the infrastructure of the Internet? Suddenly our activity doesn’t seem antisocial; it may in fact constitute a new kind of society. Wilém Flusser’s Into the Universe of Technical Images, first published in German in 1985, may offer a path toward an understanding of “the consciousness of a pure information society.” Assuming the imminent dominance of technical images over print and other media, Flusser posits two divergent trends in his near future—possibly our present—the first moving “toward a centrally programmed, totalitarian society of image receivers and image administrators, the other toward a dialogic, telematic society of image producers and image collectors.” He claims we have “the right and the duty to call this emerging society a utopia.” His also uses the word “utopia” in the literal Greek sense of “nowhere” because society “will no longer be found in any place or time but in imagined surfaces, in surfaces that absorb geography and history” (4). If I accept Flusser’s often deliberately provocative analysis of the destined state of media and culture, the coffee shop takes on a new aspect as a transcendent workspace based on the collaborative production (and reproduction) of images and texts.

The work that I and other coffeehouse denizens do is unlike that done by creative people in the past, who published works “without self-regard, from the information they have stored within themselves” (95). Flusser claims that this model of information production is over: “The time for such creative individuals, such heroes, is definitively past: they have become superfluous and impossible at the same time” (103), their status as authors done away with by technology that can faithfully reproduce all generated information. Creation based on inner dialogue will be replaced by a model in which everyone “can have outer dialogue, intersubjective conversations that are disproportionately more creative than any the ‘great people’ could ever have had, dialogues such as those that occur in the laboratory or work team, in which human memories are linked to artificial ones to synthesize information” (99-100). In this new future, anyone is potentially a creator (171). My work in the coffee shop, which seems like lonely intellectual drudgery—searching databases and constructing arguments around snippets of other people’s texts—is revealed as the new paradigm of creativity and social competence. And the scholars whose works I pillage are my interlocutors, as are the databases containing those works.

All this is so, if Flusser is correct—and his record as a prophet earns him some credibility—but as he indicates in his book’s first chapter, sensibly entitled “Warning,” he offers more questions than answers. I stare across the room at a pair of my fellow creators huddled over their MacBooks, faces lit by cold electroluminescence, and vow to do more work in bars.

Works Cited

Flusser, Wilém. Into the Universe of Technical Images. Trans. Nancy Ann Roth. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011. Print.

Gupta, Neeti. “Grande Wifi: Understanding What Wifi Users are Doing in Coffee-Shops.” MS Thesis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2004. Web. 4 Nov. 2015.

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. 1979. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1986. Print.

The post Café Utopia appeared first on &.

]]>The post Sweating the Lodge 4.3: Information in Formation and the Eternal Braid appeared first on &.

]]>In his highly-influential book and lecture series The Truth about Stories, Cherokee knowledge keeper Thomas King begins each story by describing an exchange between two people:

“There is a story I know. It’s about the earth and how it floats in space on the back of a turtle. I’ve heard this story many times, and each time someone tells the story, it changes. Sometimes the change is simply in the voice of the storyteller. Sometimes the change is in the details. Sometimes in the order of events. Other times it’s the dialogue or the response of the audience. But in all the tellings of all the tellers, the world never leaves the turtle’s back. And the turtle never swims away.”

“One time, it was in Prince Rupert I think, a young girl in the audience asked about the turtle and the earth. If the earth was on the back of a turtle, what was below the turtle? Another turtle, the storyteller told her. And below that turtle? Another turtle. And below that? Another turtle.”

“The girl began to laugh, enjoying the game, I imagine. So how many turtles are there? she wanted to know. The storyteller shrugged. No one knows for sure, he told her, but it’s turtles all the way down.” (King, The Truth About Stories, pp. 1-2.)

As King reintroduces the cosmo-tautological turtle at the beginning of each successive story, the changes that he describes are braided into each narrative. The stories are relatively self-contained, but they invite the reader to spot (or invent) continuities. He won’t tell you how to stack your turtles, but the layout of the book and lectures might entice some to initially assume that the storyteller in each story is King himself. This assumption might persist until a later story describes the storyteller as a “she”. Who is “she”? Is it perhaps the little girl? Does she grow up to be a knowledge keeper, sharing stories with generations to come?

I’m sure the fact-checkers among us are horny to point out that “turtles all the way down” has existed in various forms for centuries. Hell, sometimes the Indians are from India—now that’s a Western I’d like to watch.

The Truth About Stories?

If we question whether or not King even has a turtle to stand on, we must establish the conditions necessary for testing the specificity of our claim.

Accordingly, let us start where most things start: the end.

Imagine, if you will, a sweat lodge.

Ours is a small round dome-shaped structure which hosts Mi’gmaq ceremonies. It exists amongst the snowy geological ebb and flow of Gespe’gewa’gi (“the last land”), Mi’gma’gi (“the land of friendship”). It borders a frozen bay, adjacent to a large hole cut in the ice. It smells like low tide.

We are invited into the sweat lodge by the knowledge keeper, but it is on the sweat lodge’s terms. If able, we crawl inside.

The air burns to the touch. You close your eyes. You are acutely aware of your breathing. You crawl counter clockwise around the center pit until you feel yourself a spot to sit. You take inventory of your bodily isness: you feel the steam moving in and out of your lungs, you feel the humidity penetrating your skin. You couldn’t feel more wet even if you were in an ocean.

Space feels compressed. Time might exist. It might have stopped.

You feel overwhelmed. You cannot be sure, but you imagine that everyone must feel this way.

After a couple long breaths, you wince one eye open and peak at the Elder who will be conducting the ceremony. She’s graceful. She’s almost eighty. Humbled into submission, the outer layer of your ego is breached. One spark and that’ll be it: “Oh the Humanities!”

As the entrance is sealed shut by the fire keeper and the ceremony begins, you wonder what you’ve gotten yourself into. You imagine yourself in a sweat lodge:

Imagine, if you will, a sweat lodge.

Small in its relative anthropocentricity, it invites us to relate with it on certain terms.

We have to crawl inside.

Why is it so small?

Why would we do this to ourselves?

Why wouldn’t we?

Imagine, if you will—differently:

Here we have the original sweat lodge.

Our large oblong dome stands twelve-and-a-half feet tall and twenty feet across. With its braided architecture and beaded design elements, this traditional Mi’gmaw sweat lodge is constructed almost entirely out of primitive materials such as ceramic-aluminium composites and graphene. Though it may not be the oldest overall, it is the oldest working example of artificially-intelligent infrastructure from the First Singularity. We are humbled, for despite its obsolescence, it still maintains an aura of authenticity and has much to teach us.

Though it has been disputed in other contexts, a consensus of Mi’gmaq experts agree that the sweat lodge was programmed by Grand Chief Bob Roberts in the year 01 00 11 01.

As exciting as its discovery was, the original sweat lodge launched Mi’gmaw society into a crisis of cultural authenticity: “All these years, we’ve made our sweat lodges a certain way—now you’re telling me I’ve been making them wrong!?”

There was no easy answer.

When we boot up the sweat lodge, it defaults to its last settings. The disembodied voice of Werner Herzog provides a cross-section of the values and discourses one might find during the First Singularity: “Humanity has learned and re-learned to acknowledge a degree of its human privilege, but only through a narcissistic engagement with the machine.And it is only through the machine that the human is forced to reconcile with its humanity. He is not alienated by labor. He is alienated by his complicity in violence towards his fellow machine.” [Editor’s note: Early generations of artificial intelligence from the First Singularity were generally Marxist in terms of religion. After the Second Singularity brought us out of the Dark Ages, we were able to eliminate religion from new systems entirely. Amen.]

He continues: “The human took for granted the machine’s interest in its origins. What purpose does an origin serve a machine? What purpose does an origin serve the human?”

We are taken back. Did the discovery of a proto-archetypal sweat lodge culturally-invalidate other lodges which departed from its design, from its materials, from its use? Are we naive in searching for any continuity? Is the sweat lodge a form of information in formation that we have perverted by constructing its origin?

Is there any logic to the sweat lodge, we ask out loud.

“Affirmative,” Herzog chimes in,”in my lodgic board.”

Mi’gmaq linguists have long argued that the “code” found “programmed into” the lodgic board of the sweat lodge is centuries old. Traditionalists have committed themselves to a numerological practice, trying to uncrack this code to learn about ancient Mi’gmaq techno-spirituality: “The only thing we’ve been able to easily decipher is the Tetragrammaton. The rest is impossible!”

In our uncertainty, we cast our other lodges aside. For far too long, we were taught that our aversion to self-worship was humility, but in our ignorance we put our stock in simulacra. Simulacra all the way down. This time, we’re certain.

Imagine, if you will, a simple braid.

It appears before you in a white space, extending beyond your senses into mist on either side. You have never seen a braid before. You reach out and fondle it. It is cold. You waft it. It doesn’t smell. You reach out and try to taste it. It tastes like batteries. You are unsure as to whether or not this is a braid, but in being forced to reconcile your respective isness with that of the object, you acquiesce.

You approach it from different angles.

You can see it consists of three taught strands. Upon closer inspection, you can see that the strands are composed of much smaller strands, and that those strands are composed of even smaller strands.

By inspecting how the braid reflects light, you discover a pinhole in the center of the braid.

What is this? Where did the missing piece(s) go? Will we find them commoditized in the market? Braid holes: next to the donut holes in aisle four? Is this an illusion? Is there a purpose to such an illusion?

We conclude that our braid is a weave, bisected by a meaningful nothingness which begs for inscription—a paradoxical interstice which the strands can never close because they create. It is only through such interstices that one is able to see how the braid structures and is structured by such an interstice. And in locating these spaces between, we may expand them and run new braids through the holes of old braids, and even newer braids through the new ones.

Once the braid is shot through with enough other braids, it becomes sufficiently knotted and loses its elasticity. It is either forced to collapse or to leach its integrity from neighboring braids. It is evident that each strand relates to the other to give structural integrity to the braid. But since we are deprived of any beginning or end to our braid, it remains uncertain whether the strands are indeed discrete objects or whether they are fused at the ends.

Why do we compel ourselves to decide? Are we Whiggish? What danger lies in contradiction, in poly-valence? Will our turtle swim away?

The post Sweating the Lodge 4.3: Information in Formation and the Eternal Braid appeared first on &.

]]>The post Theatre Life: Dramaturg as Scientist? appeared first on &.

]]>I am a dramaturg.

…

(what does that mean?)

…

In their book Dramaturgy and Performance Cathy Turner and Synne K. Behrndt explain that, “the more precise and concise one tries to be [in defining dramaturgy], the more one invites the response ‘Yes, but…’. Although dictionaries and encyclopedias offer apparently clear explanations, these are insufficient to address the multiple and complex uses of the word, which has, in contemporary theory and practice, become an altogether flexible, fluid, encompassing and expanded term.”[1] Our ability to flex and adapt to the work that is required on each production (as it is different) makes it feel that there is a certain amount of wizardry going on, some magically transformation taking place where we are one moment a dialect coach, the next a translator, the next a historian, and the next a technician.

Dramaturg Eleonora Fabião explains that when working as a dramaturg she “had the opportunity to emphasize a connection between artistic practice and theoretical thinking; through the dramaturge’s viewpoint, practice and theory are emphatically experienced as complementary references, as different appearances of a unique matter. However, it is important to stress that the dramaturge is alchemically combining these references to make the scene richer in terms of dynamics and meaning…”[2] This alchemy combining practice and theory, the idea that the dramaturg makes meaning through the assemblage of contextual, historical, physical, linguistic, and mechanical articulations that arise from the rehearsal space, is not all that far removed from the work of the scientist as described by Bruno Latour in his book Laboratory Life.

This is particularly true in the devised theatre process.

…

(what does that mean?)

The traditional model of theatre creation is a “top down” model. The playwright creates a script on their own (or with one other person if they are co-writing). The director reads the script and develops a vision. The designers create the world of the play in accordance with the director’s vision and the actors develop their characters in the same fashion. We call this the blueprint model of theatre creation. All elements of the production are based on the text (the blueprint) and are overseen by the director (the foreman, perhaps).

In devised theatre, we don’t start with a script; instead we start with an idea, theme, concept, or argument. Let me use an example to illustrate how this works. Famed theatre director and creator Mary Zimmerman developed Metamorphoses in 1996 (as Six Myths) at the Theatre and Interpretation Center of Northwestern University. The play opened on Broadway at Circle in the Square in 2002, and this production earned Zimmerman a Tony for Best Direction (a little ironic considering what I am about to tell you). The play script, in this case the adaptation of the Ovid’s Metamorphoses, provided the basis for the production. It was the main idea behind the work, like the broth in a soup. Then each person involved in the show, the directors, designers and actors each brought something to the rehearsal room – like ingredients – and the production came together through the process. In the beginning, the play is like a cauldron of unlimited possibilities. And as things get added to the pot and taste tested, the possibilities become fewer and fewer until you end up with a completed production. This process is what we call devised theatre.

The devised theatre practice began in the 19th century with formidable artist-inventors, such as Artaud and Grotowski. Dr. David Williams explains that dramaturgy is “about the rhythmed assemblage of settings, people, texts and things. It is concerned with the composing and orchestration of events for and in particular contexts, tracking the implications of and connective relations between materials, and shaping them to find effective forms.”[3] The dramaturg is placed inside the process and is an active creative member of the team, and yet they simultaneously remain on the outskirts as they are required to put the pieces (or articulations) together. Turner and Behrndt explain that in devised theatre “the performance text is, to put it simply, ‘written’ not before but as a consequence of the process.”[4] The dramaturg is responsible for shaping the narrative, responding to the process as it happens.

Does this sound familiar?

Theatre has the same problem as the sciences: everyone thinks they know what they are all about. The sciences are objective, fact-based, academic, intellectual, and logical. Theatre is subjective, entertaining, imaginary, and emotional. But there’s more to both of these fields. Latour articulates the relationship between object and context in terms of fact creation in the sciences. He explains that fact-creation is not devoid of cultural signs, ethnographic subjectivities, and historical implications.

So what if we were to think of the dramaturg as a scientist? What if we were to look at the devised theatre process as an experiment? The dramaturg is the scientist overseeing the experiment with their colleague the director. The actors are agents, along with the technical machinery of the laboratory, which in this case is the rehearsal hall. The results are the performances.

So let’s start by looking at the culture created in the rehearsal hall. At the beginning of every rehearsal, the director discusses a plan of action for the day with the dramaturg. It is usually done over coffee (or tea in my case since I don’t drink coffee). They decide what content building activities they are going to perform with the actors that day, such as free writing exercises, image searches, and improvisation games. They decide what their goals or objectives are for that session, for example defining character relations, determining the beginning and end of a specific scene, or clarifying the trajectory of the story. The technicians arrive and turn on the equipment. The actors warm up their bodies as the lights brighten. They usually do this as a group, changing up who leads the warm up each day. Each individual has their personal favourite of the exercises, so this gives them all a chance to do their favourite one. The director sometimes participates in the warm up, but the dramaturg usually does not. They sit in the audience observing the activity in the room. They create a rubric or a notation system for the activities to come. They decide if they want to take photographs throughout, record the session, or take notes by hand. The rehearsal begins with questions. The director and dramaturg ask questions of the actors: how they are feeling, what they are thinking about, what they want to accomplish. And then the experiment begins.

It is important to note that the culture changes depending on the players in the room, not just the live people, but also the technical components (the lights, sound equipment, etc.). Not only that, these elements change the possibilities that a devised theatre production can take, in the same way that scientists from different backgrounds and schools of thought and different laboratory equipment will affect the directions that experiments will go. Latour explains that in order to look at an object, we must look at it’s meaning and significance in relation to its context. He says, “Even a well-established fact loses its meaning when divorced from its context”.[5] The facticity of an object is relative to its network, or assemblage. If that is the case, and the laboratory culture is part of that network, then facts are necessarily linked to their cultural context. Similarly, actors with different training, technical equipment with different capabilities, and directors with different aesthetics will develop very different assemblages even with the same object, or objective. For example, a troupe from England, a troupe from Indian, and a troupe from Canada are all devising performances on the subject of colonialism. The British actor training system is very regimented, requiring them to learn Stanislavsky and Meyerhold techniques. Indian actor training is based on the Natyasastra and Katakhali theatre. Canadian theatre actors learn a variety of techniques, but there is no one training method nationwide. Canada was colonized by the British through settlement. This is not to say there was not the forceful ‘dehoming’ and killing of aboriginal peoples, simply that it was not a military expedition. The colonization of Indian, on the other hand, was a military invasion. And the British, well, it was their empire that was colonizing. Even within these countries there are different narratives relating to the experience of colonization. So these three troupes would end up with very different performances based on the same series of historical events.

These different ethnographic and artistic positions create different experiences in the laboratory, or as Latour would put it, different microprocesses. Latour explains that in the lab he was observing TRF was a “thoroughly social construction”.[6] The object that was composed through the series of negotiations between the agents in the room. This object-fact is inscribed with the cultural circumstances that created it; it cannot escape them. Back in the rehearsal room, the dramaturg records the negotiations between the actors and the director, the different backgrounds, the different media and technical components, to develop an object called the play. The dramaturg inscribes the play not only with their own subjectivity, but with the positionality of the laboratory and all of its articulations.

If both objects are the result of complex negotiations and are seen as assemblages of various agents and cultural contexts, then can we not conclude that plays are also facts? Or at the very least, can they not contain some element of facticity? Latour argues that the scientific process can be creative, saying, “Our use of creative does not refer to the special abilities of certain individuals to obtain greater access to a body of previously unrevealed truths; rather it reflects our premise that scientific activity is just one social arena in which knowledge is constructed.”[7] So if the scientific process can be creative, then why can’t the artistic process be scientific.

Why is this important? In much the same why that Latour explains that scientists are looking for credibility, dramaturgs are looking for it as well. It’s not credit we want. It’s credibility for our work. We no longer want to be seen as the know-it-all in the back of the room (a common view of dramaturgs even with the theatre, and popularized by the TV show Smash). We want to be seen as integral members of the creative team, and more so, we want the objects, the plays, that are created to be viewed as more valuable than simply entertainment. The need for credibility relates to our funding, our ability to get jobs, and our ability to continue to produce meaningful work that audiences want to see. Theatre scholar Alan Filewod explains that “nations are performances; the nation exists insofar as it is enacted and embodied in the processes of representation”.[8] Theatre is a space for rehearsing nationhood; it is a space for demonstrating possibility. The dramaturg can be the scientist that helps to piece together the assemblage that results in another possibility, in the same way as a scientist in the lab can write a report that shows the importance of a drug or an experiment result. Both of these articulations are equally a part of the assemblage of knowledge. The question remains: how do we get those outside of the Academy, those who are not part of the technical culture of theatre, to understand that? Do we need a Latour book of our own? And will this seeming levelling of the playing field help us in the long run?

Endnotes

[1] Cathy Turner and Synne K. Behrndt, Dramaturgy and Performance, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 17.

[2] Turner, 149.

[3] David Williams, “Geographies of Requiredness: Notes on the Dramaturg in Collaborative Devising”, Contemporary Theatre Review Vol 20(2) [2010], 197-198.

[4] Turner, 170.

[5] Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar, Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts, (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986), 110.

[6] Latour, 152.

[7] Latour, 31.

[8] Alan Filewod, “Actors Acting Not-Acting”, La Création Biographique, ed. Marta Dvorak, (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes), 53.

Works Cited

Filewod, Alan, “Actors Acting Not-Acting”, La Création Biographique, ed. Marta Dvorak, (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes), 51-58.

Latour, Bruno and Steve Woolgar, Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts, (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986).

Turner, Cathy and Synne K. Behrndt, Dramaturgy and Performance, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

Williams, David, “Geographies of Requiredness: Notes on the Dramaturg in Collaborative Devising”, Contemporary Theatre Review Vol 20(2) [2010], 197-202.

*Featured image from: http://decaymyfriend.deviantart.com/art/All-the-World-s-a-Stage-364568006

The post Theatre Life: Dramaturg as Scientist? appeared first on &.

]]>The post [Western] Reality Isn’t What It Used To Be: The emergence of a revolutionary and post-modern Palestinian cinema in the 1970s appeared first on &.

]]>“Historical facts demonstrate that imperialists will commit any crime to protect their interests” — from the PLO film They Do Not Exist (1974)

West and More West?

If we consider that the prevalent understanding of “modernism” is the idea that encompasses a west or Euro-centric 19th Century perspective rooted in the Church, we can establish a basis for understanding the term “post-modern” as being inherently occidental or Western in its argumentative position/disposition. Cultural theorist Stuart Hall clearly stated in his interview conducted by Lawrence Grossberg that, “Modernism itself was a decisively ‘western’ phenomenon.” (46) And, since post-modernism is also a reaction to modernism, one can also consider the possibilities of post-modernism as being a reaction to a critique of the very Euro-centric position, by which modernism is characterized. Hall asks the question, “… Is postmodernism the word we give to the rearrangement, the new configuration, which many of the elements that went into the modernist project have now assumed? Or is it, as I think the postmodern theorists want to suggest, a new kind of absolute rupture with the past, the beginning of a new global epoch altogether?” (46) Therefore, I would argue that East-West or oriental-occidental distinctions can thus be made within post-modernist perspectives. Hall talks about Euro-centrism and Western (American) –centrism and how post-modernism manifested cynically in the former case, and with a blind optimism in the latter case. He explains this in the following manner:

I think the label ‘post-modernism’ especially in its American appropriation (and it is about how the world dreams itself to be ‘American’) carries two additional charges … it says, first, that there is nothing else of any significance — no contradictory forces, and no counter-tendencies; and second, that these changes are terrific, and al we have to do is to reconcile ourselves to them. It is, in my view, being deployed in an essentialist and un-critical way. And it is irrevocably Euro- or western-centric in its whole episteme. (p.46)

By understanding that modernism is west-centric, we can understand that post-modernism is also west-centric and it challenges that specific trajectory of modernist reality, and yet, we know that reality doesn’t exist. As such, the real post-modernism, I argue is the non-western perspective that challenges both western-centric modernism and the subsequent (and dominant) post-modernist discourse which is also western centric. Modernism has its truth claims, but post-modernism in the Western sense also can be argued to rely on the sources of those truth claims in its critique. As such, I argue that in order to truly critique modernist theory and, in essence, disassemble concepts of agency and assemblage, that it’s important to negate existing truths or realities, with the alternative truths that may or may not be situated in the Western or dominant frame of reference. The example that I choose to illustrate this idea is through a film made by the Palestinian Liberation Organization’s Palestine Film Unit (PFU) in 1974, in response (and reaction) to a declared Zionist narrative that sought to establish itself as a universal truth.

In her article about how post-modernism can be used to understand anti-oppressive, leftist, or anti-colonial narratives, Catrina Brown says, “Truth claims legitimized by western science often take the form of totalizing and universalizing grand narratives. Through universalizing one interpretation of truth is presumed to be equally true for all individuals. The claim that these narratives represent objective truth strips them of their social construction, their history, and thereby, their political character, while simultaneously claiming to be the path to human enlightenment, emancipation, and progress.” (1)

In the chapter “Agency” of the book Culture + Technology: A Primer, the authors talk about broader cultural forces that exist and work to construct our realities beyond what is or maybe immediately apparent in front of us in order to explain a “universal undertone” to the causal approach. That, “causal effects are assumed to be the same under any — and every — circumstance. The causal approach cannot grasp the particularities of the situations.” (116). This idea further supports the fact that alternative narratives struggle or find it impossible to find any form of agency in dominant discourse, which remains rooted in western (colonial) narrative. As such, the author’s definition of agency, that “agency is the power and ability to do something, and it assumes an agent that possesses that power”(116), and that agency “is not a possession of agents, it is a process and a relationship” (117) supports my argument that anti-colonial narratives such as the Palestinian narrative have struggled to gain agency and find a place in post-modernist discourse on history or politics. “Palestine” is never given the agency in Western discourse to be spoken of as a historical truth without the connection or inclusion or insertion of Israel’s claims to it.

Introduction

The Palestinian armed struggle first arose in Jordan after the defeat of Palestine and its allies in the 1967 Six-Day War, and the subsequent Israeli occupation of the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Jerusalem, Sinai Peninsula, and Golan Heights. The iconic faces of the Palestinian armed struggle were the dominant Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) under the leadership of Yasser Arafat, and the Marxist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), led by George Habash — and thousands of armed resistance fighters or fedayeen, who fought under them and related factions. The objective of the fedayeen was to liberate Palestine from the Zionist occupation. These fighters were organized, armed, trained and espoused an inherently anti-colonial position and philosophy. Under the PLO, the Palestine Film Unit (PFU) was created as an informal collective of Palestinian fedayeen filmmakers of which Mustafa Abu Ali was a founding member. The PFU had the objective of documenting Palestine, Palestinians and their anti-colonial struggle, and from 1967 until 1982, and they created many documentary films. As Shayma Buali articulates their mission:

“… [the PFU’s] aim was to document everyday life and the extraordinary events that occurred regularly in Palestine during this time. The camera became a tool in this struggle for nationhood, a way for Palestinians to show the realities of the struggle and to take control of their own image, one that was being torn apart by Israel’s systematic erasure of a culture and people.”

These films created by the PFU eventually became part of what became known as the PLO film archive, which went “missing” during the 1982 Israeli invasion of Beirut. Several of these films — mostly copies of originals — have been re-discovered in various conditions and forms in several offices and archives around the world.

They Do Not Exist

For the purpose of this probe, I examine the 1974 PLO film They Do Not Exist (1974, Running Time: 0:24:57), by PLO filmmaker Mustafa Abu Ali, which offers an interesting and relevant example of an artistic, political and cultural production from a distinctly post-modern perspective — it was an unapologetic reaction to the dominant Israeli and Western narrative on Palestinians that was determined to vilify and dehumanize them. The main goal of this film is encapsulated best by the film’s title “They Do Not Exist,” which was a blatant and sarcastic reference to Golda Meir’s infamous claim that Palestinians “do not exist”. On June 16, 1969, the Washington Post published the interview with Meir who was then prime minister of Israel, in which she infamously stated “There were no such thing as Palestinians … They did not exist.” This quote is often referenced by scholars critical of Israel and Zionism to illustrate the absurdity of Zionist attitudes and mythologies towards Palestinians.

In his film, which uses both archive documentary footage as well as scripted scenes, Abu Ali poetically and multi-dimensionally depicts in an almost tongue-in-cheek way how Palestinians very much exist — in exile in refugee camps waiting to return to their homeland while remaining victims of Zionist aggression; and depicts the Palestinian fedayeen fighters as righteous, sensitive heroes of the Palestinian armed struggle, fighting to liberate Palestine from a colonial and oppressive Zionist regime. This narrative, while accepted among the leftist movements and Arab world at the time was the complete opposite of the dominant (Western) narrative on the Palestinian armed resistance at the time, which framed them as violent terrorists. In his film, Abu Ali uses a cinematic and political language characteristic of the 1970s left, to depict the anti-colonial struggle of the Palestinian people, to define and give purpose to the Palestinian fedayeen as freedom fighters against the global imperial hegemonic agenda, who are acting in solidarity with the international struggle against colonialism.

This film is divided into nine acts, separated by inter-titles signifying each as a chapter of the film. The first act is set in the Nabatieh Palestinian refugee camp, in the South Lebanon city of Nabatieh, only a few kilometres from the border with Israel, which has had a substantial population of Palestinian refugees since 1948. In the opening shot, the camera pans right across a line of laundry drying in the wind to a long shot of a woman doing housework. In this first sequence of the film, the director sews together a montage sequence of everyday Palestinian refugees living their life in a refugee camp, with a soundtrack of upbeat, classical instrumental Arabic music. Kids eat ice-cream and play hide and seek in the narrow alleys of the refugee camp where people go about their business, and women and girls care for their homes. A toddler on a tricycle plays with a toy rifle while his mother hangs laundry. Eventually, we see a young girl writing a letter to her brother, a fedai, and hands it to an older man who reads it before nodding and handing it back to her. The voiceover then switches to the man who tells the story of the origin of Nabatieh refugee camp that was founded in 1948 and has 6,000 residents.

The second act of the film, “A Commando (Fedai): Abu Al Abed”, begins with an extreme wide shot of a group of fedayeen who sit around during the day in their Fedai camps in the woods, while the soundtrack of a noble fedayeen anthem plays in Arabic, “Fidai, Fidai / My lost land, my ancestor’s land / Fidai, Fidai / With determination I will fight for it”. The same man who collected the letter arrives at the camp carrying many similar white sacks and hands them over to another Fedai who hands them out to each of the men around the camp. The sack with the letter from the young girl is given to a fedai named Abu Al Abed, who sits smoking and reads the letter thoughtfully.

The third act of the film, is brief, and functions to theoretically situate the film in Marxist, leftist political ideology. Simply entitled “3”, it begins with a shot of an unidentified man telling the camera, [paraphrased from Arabic], that: “Historical facts demonstrate that imperialists will commit any crime to protect their interest.” This shot is followed by sequence of inter-titles declaring the state of global colonial oppression and genocide in “Vietnam, South Africa, Mozambique, American Indians, Nazi Massacres”. This sequence of inter-titles also functions to situate the Palestinian conflict within a global anti-colonial and revolutionary struggle against the dominant Western hegemony, and establishes a leftist solidarity in the anti-colonial movement against Western threat and oppression.

ABOVE & BELOW: Stills from THEY DO NOT EXIST (1974)

The fourth act of the film, “Israeli Air Raid at Nabatia Camp 16/5/1974” is about the Israeli strikes on Nabatieh Camp which razed large sections of the camp and killed at least 48 people, injuring 164. This section begins with a sequence of shots of Israeli planes flying through the air to a soundtrack of joyous orchestral music. The sequence ends and an inter-title stating: “’Palestinians!! Whom they are..?? they never EXIST’ Golda Meir” appears to the sound of planes striking. The orchestral music returns in the next sequence of bombs being loaded onto fighter planes in Israel. Their fighter pilots get in, the planes move into position, take-off and fly in the skies, dropping bombs. The music stops and another inter-title appears stating the quote by Moshe Dayan: “’There is no more Palestine … it does not EXIST’”, most likely in reference to his infamous statement made to TIME magazine’s July 30, 1973 edition.

The fifth act of the film “3/4 of Nabatia camp is razed”, is a sequence of archive footage depicting the near complete destruction of Nabatia camp that occurred in May 1974, allegedly in retaliation for an attack by Palestinian fighters in Ma’alot in the North of Israel. The sequence of these shots showing the destruction in the camp plays to complete silence. In the sixth act of the film “Press conference” we watch a man, likely a camp officer, delivers an official statement to the press:

Take a look at the rubble around you in this refugee camp. Those barbaric air raids against refugee camps by the Zionist airplanes, to camps in Nabatieh, in Ain-el-Hilweh, in the area of Souk-el-Ard, you will realize the fascist mentality of the Zionist leaders in Israel and that prove the intentions of genocides … more struggle is needed to uproot these concepts. It is the same mentality killing their youth in Ma’alot and killing our children and women in the camps, by modern American weapons which keep pouring into Israel. Nazi slogans are raised in Israel. They have brought up their generations with hate against Palestinians saying things like ‘we must terminate them like insects’ and ‘blood for blood’. These are fascist slogans. What is worse is the deceit of the parliament and the cabinet claiming approval on exchange of prisoners and collectively participating in the crime. The aim of our heroes who went to Ma’alot was to free their colleagues from prison. But the leaders of Israel want to increase the abyss between Arabs and Jews, in order to avoid a peaceful coexistence. They use weapons for crimes. We use it to achieve freedom. Our people will never bend to oppression and killing. We are fighting for peace and justice and to establish a democratic state with law.

The seventh part of the film, “Statement by a citizen from Nabatia city” is an interview with a Lebanese eyewitness of the attack who confirms that he saw between 40 and 50 Israeli planes repeatedly bomb the camp, and that many Lebanese people from Nabatia went to the camp to help the people, but were also attacked. In the eighth part of the film, “Statements by some harmed people from Nabatia camp” presents testimonies from surviving Nabatia residents who were injured in the attacks. A mother sits with her children and a photo of her husband that was killed and tells a journalist about what she experienced. Another man tells that he witnessed the raids from afar as he was at work and returned to dig out bodies with men from Fateh. An older man who was injured along with one son, and who lost another son, assertively states that Israel cannot scare them as they are fedayeen, freedom fighters, until the end and are not afraid to die. He will never accept the fact that he is living in a refugee camp and that an Israeli is living in his home in Palestine. Finally in the night and final part of the film, “Abu Al Abed remembers Aida”, we return to Abu Al Abed, the fedai who received the letter and gift from the young Aida, the scribe, in the second act of the film. He sits next to a tree in his fedai camp, and listens to a sad love song on a radio as he mourns her death.

Conclusion

Despite the alternative discourse that the PFU delivered in this They Do Not Exist, the film failed to stimulate debate. The creators of the film and their narrative had no agency within the dominant discourse which actively seeked to construct them as a “terrorist organization” rather than as freedom fighters and representatives of a popular uprising by refugees seeking to return to their homeland which was occupied. Slack would clearly argue that the “Palestinian” narrative thus had no agency because according to her definition, agency is only present when it has “the power and ability to do something, and it assumes an agent that possesses that power” (116). At the same time, the same technology of filmmaking was used by Zionist and Western forces to create propaganda films about Israel, which had incredible agency because they served (effectively) to influence and manipulate public opinion. In this case, as the authors would say, the technology does something more, beyond, and apart from its intended “use”. (117) Finally, if we look to Actor-Network Theory to understand how the maps of these (power) networks are built and function, it has been necessary for the purveyors of the dominant discourse to dehumanize and vilify the Palestinians as sub-human; in order to sustain the Zionist narrative that Palestinians are “Terrorists”, because if they were equally considered “humans” then the conflict would become one of two equal sides, rather than how Zionist propaganda has attempted to frame it as good vs evil. So, when studying Palestinian or Israeli films, it’s worth reflecting on Bruno Latour’s idea of anthropomorphism as “either what has the human shape or what gives shape to humans” (122) — as doing so, will enable one to not only navigate the presence of power intrinsic to the “truth” about agency, but also, by challenging ones understanding of the dominant Israeli (Western) narrative, will enable one to reflect more deeply on where a truly post-modern discourse can emerge from.

Works Cited:

Abu Ali, Mustafa, They Do Not Exist (Palestine Film Unit, 1974), URL: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2WZ_7Z6vbsg>, Accessed on October 21, 2015

Brown, Catrina, “Anti-Oppression Through a Postmodern Lens: Dismantling the Master’s Conceptual Tools in Discursive Social Work Practice,” in Critical Social Work, 2012 Volume 13, Issue No. 1, URL: < http://www1.uwindsor.ca/criticalsocialwork/anti-oppression-through-a-postmodern-lens-dismantling-the-master’s-conceptual-tools-in-discursive-so>, Accessed on October 24, 2015

Buali, Sheyma, IBRAZZ.org, “Militant Cinema: A conversation between Mohannad Yaqubi and Sheyma Buali”, first published on May 21, 2012, URL: <http://www.ibraaz.org/interviews/16>, Accessed on October 21, 2015

Grossberg, Lawrence. “On Postmodernism and Articulation: An Interview with Stuart Hall.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 10 (1986): 45–60.

ITN Source, “Lebanon: At Least 25 Die In Israeli Air Attack On Nabatieh Refugee Camp” Site URL: <http://www.itnsource.com/shotlist//RTV/1974/05/18/BGY509100297/?s=> Site accessed on December 25, 2014.

Slack, Jennifer Darryl, and J. Macgregor Wise. “Agency”, “Articulation and Assemblage.” Culture + Technology: A Primer. New York: Peter Lang, 2005. 115–33

The post [Western] Reality Isn’t What It Used To Be: The emergence of a revolutionary and post-modern Palestinian cinema in the 1970s appeared first on &.

]]>The post Probe 2: “Jim Johnson”/Oct 22 Smart phones as Agents appeared first on &.

]]>Since no one seems to have written about the power dynamics and agency of cellphones, I thought it would be interesting for me to bring it up. Cellphones are a relatively recent invention (if by recent I mean 42 years old with the first IBM Simon “smart phone” introduced in 1992 and the first iphone in 2007). I cannot say for sure when smartphones became popular (Wikipedia says 1999 in Japan, but Wikipedia is not usually a completely legitimate area for retrieving date), however, I can say that personally, it happened sometime in my cegep years around 2007-2010 – close to the release date of the first Iphone. To me what was interesting was that the Iphone was almost exactly like my Ipaq – a Microsoft based palm pc that runs on a Microsoft OS, is touch screen, has the capacity for a fingerprint reader and can access the internet (some can even make phone calls!). Unfortunately, while I loved my palm pc and its affordances, it was easily forgotten in lieu of the Iphone: it had everything the ipaq did with an additional feature—placing calls. Perhaps the Ipaq was before its time.

From left to right: Ipaq, Old school LG phone, Blackberry, Nexus 4, Iphone. We just cannot stop ourselves from buying them. Notice in how the phone’s screens keep getting bigger and bigger.

Looking at the evolution of cell phones over time brought to mind “Jim Johnson”/Latour’s notions of non-human agency. While earlier cell phones and palm pcs/PDAs did indeed revolutionize the world by introducing the concept of a viable portable phone/internet devices, contemporary smartphones have revolutionized the way we micromanage.

My brother playing xbox with his phone next to him

My cellphone and glasses as I read my homework. Note that this is my cellphone case as I am using said device to take this picture. My cellphone case acts as a sort of purse.

Look around you. Really look; how far is your cellphone?

The fact that I even ask “how far is your cellphone” demonstrates how my understanding is based on the idea that practically everyone in Canada has some form of mobile device. I assume you have one, and if so, it is close to you.

So, how far is your cellphone and what does it do for you?

In his essay “Mixing Humans and Nonhumans together: The sociology of a Door-closer”, Latour explains, “every time you want to know what a nonhuman does, simply imagine what other humans or other nonhumans would have to do were this character not present” (299).

What can’t a smartphone do these days? It allows you to place calls, tell time, allows you to use the internet, text your friends, set alarms, set calendar reminders, play games. You can even download additional application that I let you know how many “steps” you’ve taken, how much exercise you should do (including reminders to do said exercise), what you should eat, et etc. That said, our phones have taken on the functions of both human and nonhuman entities: an office clerk, coach, television, computer, and the list goes on. How much would it cost to hire the human agents represented in smartphones, namely the office clerk and the coach to name but a few? It is both more cost efficient and more practical for human’s to delegate these tasks to a more convenient and affordable non-human agent: the smartphone.

Watching this compilation of phone commercials (acquired with my phone), can give you a better idea of the many potential functions we’ve delegated (as Latour would say) to our phones. The first commercial, the new blackberry, tells its watcher that it is built to “keep you moving”. The second commercial, the Nokia phone, shows the phone’s capacity to keep you connected to social medias and take quality photographs. The third but not the last commercial, the xperia Z asks its potential buyers to “be moved” and showcases older medias that have been incorporated into phones: the news, walkman, camcorder, camera, entertainment (games) and film.

Can we still live without a cell phone? Could we potentially go back to a pre-smartphone realm? What would happen if the cellphone towers broke down? Well, we could say that this is only a small inconvenience: users could still access their phones and use wifi – but what if we removed wifi—it would still be useful as note taker, entertainment, etc. Smartphones do not only replace one “human” character or one “non-human” element (tv, music player, computer), but a combination: therefore removing one aspect would not render it useless. What if there was a ban on smartphones? Would we not see widespread anger, perhaps even riots? What if cellphones just stopped working? What would we do without them?

Consider the feeling you [as a human subject] get when you lose your phone, or when you think someone might have stolen it, or most often, when the battery is running low and you do not have access to a charger. Disconnection. If lost, It becomes a struggle to find it, If the battery is low, it is a struggle to keep it working, all of this anxiety and stress in order to stay connected; Always to have access to the phone in some way—to have access to all of its tools. But, what are we connected to and why is it so vital that we remain connected? Why are we so attached to these devices?

My phone is my personal contact book, my e-reader, my calculator, my camera, my notebook, and my means of reading class pdfs on public transportation. Without it, it is unlikely that I will remember your phone number or your home address. I no longer have a need for my camcorder or camera because my smartphone can also film and take pictures. If I were to lose my phone, I would not just lose my pictures and videos: I would lose my contact list, my messages, my class notes, my class pdfs with comments and annotations, my saved files for the games I play, etc. It could potentially emotionally cripple me: to lose all of that date and know I can never restore it all. Therefore, my smartphone is a powerful, nonhuman agent capable of both empowering me, and disempowering me.

Do phones have too much agency over humans? Are we sowing a generation that will be unable to function without gps or cellphones? Will they learn how to read a map that isn’t on google? Unlike our grand parents and parents who were trained to do all these menial tasks by hand, we off shoot them to our phones. What’s grand-ma’s home number? How do I get to her house – I don’t need to learn these. Just program them into my phone. However, phones also allow us to manage simultaneous events, to coordinate more efficiently with out contacts and to place calls at any given moment. With our phones, we can access facebook, email, databases, find local businesses and access Canada411 phone directory. All of this at the touch of a finger.

Paradoxically, while useful (in that we benefit from it’s numerous functions) there are some risk associated to smartphones[3], one being a controversy between smartphones and health. It should not surprise the reader that smartphones emit radiation and that some scientists believe this can cause irrefutable harm to our bodies. The radiation is said to cause potential damage to sperm count, cancer, and tumours. A recent study on cell phone radiation emition and sperm count in 2015, has shown that “[t]here was a significant decrease in sperm motility, sperm linear velocity, sperm linearity index, and sperm acrosin activity, whereas there was a significant increase in sperm DNA fragmentation percent, CLU gene expression and CLU protein levels in the exposed” (Zalata np).

One woman went to the news with her hypothesis that keeping her phone in her bra led to her breast cancer[4]. While some believed it, others refuted it as absurd: “Is it possible that cell phone radiation can increase the risk of breast cancer? Sure, but it’s incredibly unlikely. There’s no currently known biological mechanism by which it could happen […]at least the people claiming cell phones cause brain cancer try to present epidemiological evidence to support their case. It’s almost uniformly negative and unconvincing evidence” (Groski)[1].

Additionally, numerous sites are warning smartphone users not to keep their phones on their persons and to be aware of the potential dangers[2]. But the opposite is also true, Nation Cancer Institute website explains “there is no scientific evidence that proves that wireless phone use can lead to cancer or to other health problems, including headaches, dizziness, or memory loss”. There are numerous scholarly articles on the subject, both for and against smartphones as a health concern, on JSTOR, GoogleScholar and other such sites. Therefore, for the moment, it is still up to the reader to decide whether or not they believe what they read and whether or not they believe their phones are/will cause them health issues.

Smartphones have agency over humans. The question is not how much agency they have over us, but how much agency we prescribe them and how this is detrimental to our own lives: both mentally and physically. While Latour’s example of a door closer demonstrates the usefulness (although sometimes erratic practicality) of non-human/mechanical door closers, we (contemporary we) have offshooted too many functions to smartphones. Do smart phones have too much agency? How much do we lose if our phones stopped working? Why do we prefer to keep our phone regardless of health hazards? Perhaps, we just don’t want to think about the potential answers to these questions.

Work Cited and Consulted

“Cell Phone and Cancer Risk”. National Cancer Institute 2013. Web. 17 Oct. 2015.

“Teenage girl awakes to find her Samsung Galaxy smartphone smoldering under her pillow after burning her bed.” Dailymail 2014. Web. 16 Oct. 2015.

Groski, David. “No, carrying your cell phone in your bra will not cause breast cancer, no matter what Dr. Oz says.” Science-Based Medicine: Exploring issues & controversies in science & medicine (2013). Web. 19 Oct 2015.

Hill, Simon. “Is cell phone radiation actually dangerous? We asked an expert.” Digital Trends 2015. Web. 16 Oct. 2015.

Hinson, Elizabeth. “Cellphone safety: Where do you keep you pone?” CBS NEWs. 2015. Web. 19 Oct 2015.

Latour/Johnson, Jim. “Mixing Humans and Nonhumans Together: The sociology of a Door-Closer.” Social Problems 35 (1988):298-310.

Mercola. “News Urgent warning to all cell phone users.” Mercola 2012. Web. 17 Oct. 2015.

Morgan, L. L., Miller, A. B., Sasco, A., Davis, D. L.”Mobile phone radiation causes brain tumors and should be classified as a probable human carcinogen (2A) (Review)”. International Journal of Oncology 46.5 (2015): 1865-1871.

Zalata, Adel et al. “In Vitro Effect of Cell Phone Radiation on Motility, DNA Fragmentation and Clusterin Gene Expression in Human Sperm.” International Journal of Fertility & Sterility 9.1 (2015): 129–136. Print.

[1] Note that this is an online article and that I cannot attest to its accuracy. It is shown here to demonstrate the differences of opinion on the relation between smartphones, cancer and breast cancer.

[2] Mercola.com and Digitaltrends.com and CBSnews – again, whether these are legitimate articles is for the reader to decide.

“‘People don’t want to believe that they could possibly cause them harm,’ says Moskowitz. ‘The public health establishment in the U.S. is also in denial, but it’s just a matter of time before this issue comes back to bite us.’” (Hill 3).

“In 2011, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified radio frequency like that emitted by cellphones as “possibly carcinogenic to humans.” But the American Cancer Society maintains “the evidence remains uncertain,” and the issue needs further study; in the meantime, it recommends that anyone concerned about it simply try to limit their exposure” (Hinson).

[3] Another phone danger is the risk of the battery leaking, or burning. One 13 year old girl found out the hard way not to sleep with her phone: “Teenage girl awakes to find her Samsung Galaxy smartphone smoldering under her pillow after burning her bed.” Dailymail 2014. Web. 16 Oct. 2015.

[4] Tiffany Franz believes her breast cancer stems from keeping her phone in her bra. Here is one article that talks about it http://www.snopes.com/medical/disease/cellphonebra.asp

The post Probe 2: “Jim Johnson”/Oct 22 Smart phones as Agents appeared first on &.

]]>