The post Bootcamp: Mapping Bob Dylan 1961-1966 appeared first on &.

]]>For this bootcamp I was interested in looking at what Bob Dylan calls “home”. For someone who spends 10 months on the road a year, has multiple houses, has moved from Minnesota, to New York, to Malibu, etc., I figured it would interesting to look at Dylan’s lyrics and note every time he mentions the word “home”. This of course, was a terrible idea since most of his songs (at least for the time period I was looking at) are traditional folk songs, attempting to tell an independent story. So, after wasting hours looking over his lyrics (there are about 59 of his songs that reference “home” for those who were wondering and only a very slim few actually referenced a specific place), I decided to re-watch Martin Scorsese’s’ documentary about Dylan, No Direction Home.

The first few lines of the documentary are spoken by Dylan:

The documentary also concludes with Dylan speaking about home as he tells a reporter:

After his never-ending European tour, documented by D.A. Pennebaker in “Don’t Look Back”, Dylan was involved in a motorcycle crash, although there was no official record of Dylan’s accident (as he did not go to the hospital). What is known of this incident is that it brought his recording to a halt for two years, and stopped him from touring for eight years. As can be seen from the map of Dylan’s first five active years (not only is his touring schedule insane, but he also produce seven albums in five years), Dylan needed a serious break. After his accident Dylan settled in Woodstock, NY, and played in The Band’s basement, where they created carefree music together, without the usual pressure to produce for other people. At this point, his musical style along with his physical and mental state seemed to come to rest. Dylan was finally not only physically at home, but also mentally at home within himself. He no longer had to pretend to be “a Woody Guthrie” or a “political song writer”, but could instead finally be himself. Whether or not the accident was truly an accident (Dylan merely broke a vertebrae after all), the time away from the pressure of stardom allowed him be the father and the person he needed to become.

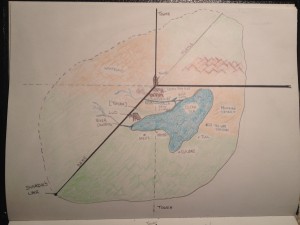

Therefore for my map, I decided to map Dylan’s busy life throughout the years 1961-1966. This was the result:

What this particular mapping method did not show me was anything about Dylan’s quest for home. Not only was this mapping process extremely long and tedious (entering each location of each concert), some of the concerts or the events that occur in the same locations do not show as well, as they are hidden under other events. It is easy not to see them or know that they are even there at all. For example, in 1964 Dylan had a concert at Town Hall in Philedelphia on September 1st, and another one at the same location October 10th, when looking at the map, it isn’t obvious that the events took place in such a way. Another problem that occurred to me was that some of these locations might not exist today as they did then. For example a high school that Dylan may have played at in 1964 may not have the same name today, so it’s hard to pin point exactly where these locations were.

The map itself also doesn’t directly show the dates of the concerts or the strain on Dylan’s travel schedule these dates created. For example, December 7,1965 Dylan played in Long Beach, CA. Dec. 8th he played Santa Monica, Dec. 9th – Pasadena, Dec. 10th – San Diego, Dec. 11th – San Francisco, Dec. 12th – back to Pasadena (Bob Dylan Set List). This can only be realized if one looks to the table beside the map, noting each concert. This mapping style didn’t allow me to best represent the rapidness of his scheduling with each stop, only the multitude of shows. Although I know from research that he wasn’t getting any rest in between shows, a quick glance at the map does not show this, however, the table does.

Despite these frustrations, a positive about mapping in this fashion is that I can enter notes on the events that occur. For example if you click on one of the black markers, I’ve been able to provide information on what has occurred to Dylan during the year it describes. However, some of the markers simply hover over the water, since they would be covered by other markers like those of the concert markers if I were to place them in their relevant areas.

One thing this map did show me that I hadn’t noticed before was that Dylan played at the same concert venue, or even in the same major cities quite often. This says something about not only Dylan’s fandom in these major cities, but also about how concert locations and planning works in general. Perhaps most importantly, it showed a massive demand for just one individual and despite the repetition of some venues, with this many places to be throughout his career, I realize that there was no time to even begin looking for home.

Works Cited

“Create and Publish Interactive Maps.” Map Creator Online to Make a Map with Multiple Color Pins and Regions. Web. 19 Oct. 2013.

Gill, Andy. Bob Dylan: Stories behind the Songs 1962-69. [London]: Carlton, 2011. Print.

No Direction Home = Bob Dylan. Dir. Martin Scorsese. Perf. Bob Dylan and B.J.Rolfzen. Paramount, 2006. DVD.

Scorsese, Martin. “No Direction Home (Intro).” YouTube. YouTube, 03 July 2012. Web. 22 Oct. 2013.

“Set Lists | The Official Bob Dylan Site.” The Official Bob Dylan Site. Web. 19 Oct. 2013.

The post Bootcamp: Mapping Bob Dylan 1961-1966 appeared first on &.

]]>The post Probe: Mapping The Dark Tower Series appeared first on &.

]]>What does it mean to map something that has already been mapped? (Or to overwrite a map?)

How do the technologies of mapping used affect the maps created?

Is it possible to map everything in order to avoid biases?

Do new technologies create more biases, or just different biases? (Do you lose old bias when new technologies are used, or do these technologies exploit previous biases?)

What can be produced when attempting to map the un-map-able?

The Dark Tower series by Stephen King has multiple worlds and portals that transport characters from one world to another, relocating them in different worlds and different time periods. In order to explain how the series was mapped, I will first explain the different worlds that exist in the novels.

Mid-World is the world where the Dark Tower actually exists. This is the only world plane where it is possible to enter the tower, itself (also known as the Keystone Tower in this reality) unlike other world dimensions where the tower is represented with the use of other items (mainly a rose). Mid-World is the world in which most of the story occurs, the land on which the Ka-Tet travels, but it also more specifically tends to reference the inhabitable portion of the world (note: the most common Mid-World measure of distance is in wheels – 8,000 wheels = 7,000 miles). It includes locations such as Gilead, capitol of New Canaan barony and Roland’s birthplace, Mejis, Tull, Eld, River Crossing, Lud (a post-apocalyptic representation of New York City) and Topeka.The terms In-World and Out-World are used to differentiate locals from foreigners. “To the In-World citizens of Gilead (barony seat of New Canaan), those baronies located far from the hub of civilization were part of Out-World” (www.stephenking.com). These terms were also used to describe Calla Bryn Sturges (In-World) versus the unknown territories and those who arrive from there (Out-Worlders).

The land found between Mid-World and End-World is referred to as the Borderlands. This is the area of small towns located on the Mid-World side of the River Whye’s banks. On the far side, the land turns to waste as it continues into End-World. Thunderclap and Discordia, after which is located the Dark Tower.

End-World is the inner most section of Mid-World. Once one has crossed the River Whye, they will come across Thunderclap and Discordia, after which appears the Dark Tower, itself. Can’-ka No Rey is the field of roses which surrounds the Dark Tower. It’s important to note that each rose in the field exists as a representation of the tower in another world/parallel existence. The Dark Tower is the axle on which the entire universe spins. It is not just a physical building, but a concept bordering on that of religious worship. Interestingly enough, the tower is not just the center of the universe. It is also the outer edge of reality. For example, if one were to stand with their back to the tower and walk away from it in a straight line they would eventually run into it again at the other end of the world as well. There is no singular path to the tower, eventually if the beams are followed far enough, all lead to the tower.

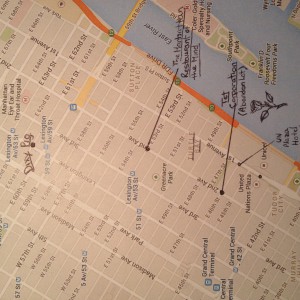

The Dark Tower series also contains different versions of Earth (as we inhabit it). There is Keystone Earth, which is very similar to “our world”. In Keystone earth time is linear. The two primary locations in Keystone Earth are Maine in 1977 and 1999 as well as (Keystone) New York City most notably in 1999 when the Hammarskjöld Plaza is built to protect the rose. New York City, alone, is a different entity, without linear time. Eddie, Susannah and Jake all come from varying New York Cities with minor differences such as Co-Op City, Brooklyn (Where Eddie is from) versus what we know in our world to be Co-Op City, Bronx. Topeka Kansas is also a part of their journey, however, it exists in a variance of Keystone Earth. Many believe that the Topeka described in The Dark Tower series is of the same realm that King wrote The Stand in – a post-plague America.

In order to travel from one world to the other and bend time, there are magic doors, or portals, that bring the characters to their desired locations. In order to complete their quest, Roland and his ka-tet must travel through time and space using these portals. This makes mapping their journey difficult.

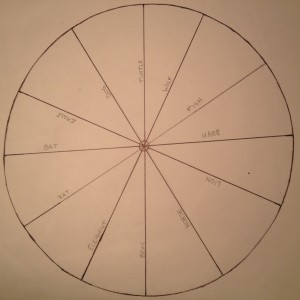

Having described the differing levels of the map, it only makes sense to describe and justify the maps I’ve included, first, since I don’t feel that they completely do the complexity of the situation justice. The map for The Dark Tower series is not a linear. The sense of space, topography and organization of the series does not solely include one illustrated map, but numerous versions and layers, if done correctly. Not only this, but the maps must be three dimensional, or even four-dimensional space (which was something I did not have the capability to do when attempting to map the series). The tower itself is at the center of every world, but as mentioned above, it does more than just occupy a space on a map (which once again is something that I couldn’t/or didn’t know how to draw).

The marked version of New York City that is included is only one version of many New Yorks described and hinted at throughout the series. It would take months to recreate every real world reference to location as well as the alternate versions such as the location of UN Plaza hotel which, in the book is located at 46th and 1st, but in real life is found at 44th and 1st Ave. Or Eddie’s version of Co-Op City, Brooklyn versus the world we know that exists as Co-Op City, Bronx (to see someone who has devoted years of their life to this topic and different mapping techniques from real world photos to music links, visit: Blog Devoted To Dark Tower Series.

My own bias appears in the limited and select maps that I chose to represent the world(s) I’ve read so much about. Personally, I chose to stay closely linked to the Tower. This requires staying within a few mile radius in Keystone New York City to represent the importance of moving towards the world’s “center” (the Tower). I chose to hand draw the maps of Mid-World and the paths of the beams in order to better represent the period which, as presented to be post-apocalyptic, reverted back to an earlier time without the technology available anymore to create the intricacies of the territory. In regards to the map of New York City that I’ve used, it is acceptable to use modern technology since the New York Cities described have not fallen apart yet. Technology is still available to use at our leisure.

The Dark Tower series embodies (and perhaps goes beyond) Moretti’s concept of Our Village’s spatial pattern, as he states” by opening with a linear perspective, and then shifting to a circular one, Mitford reverses the direction of history…[as the readers] look at the world according to the older, ‘centered’ viewpoint of an unenclosed village” (84). The world’s in The Dark Tower is somewhat like a village story, Roland sets out to find something, and ultimately returns (spoiler alert) to the same exact place he started. However, King’s concept of time and space are not linear or even circular, as they are in Whitaker’s novel, which is what makes The Dark Tower series so interesting to map out. It makes the “stylization of space” (Moretti, 85) especially difficult to map, as The Dark Tower series challenges Christaller’s idea of “Central Places” (Moretti, 86) since the marketing and economic aspect of the books are non-existent. Most of the towns in the novels are deserted; social geography is then nulled, or completely non-important. This once again shows that this long “village story” (The Dark Tower) is organized in a looser circular pattern than the village stories mentioned by Moretti. However, the centrifugal force of the novels are evident as literally the world revolves around the Dark Tower. Therefore, despite the fact that the villages don’t offer tight centers of central spaces, on a larger scale, the presence of the tower in the center of it all pulls everything tightly towards one point on the map. By centering the novels around the Dark Tower, it is possible to understand King’s intentions and his “world view“ (Siegert, 13) as represented through Gan, the creature who lives in the Dark Tower, acting as a God-like figure.

Unfortunately I was not able to map the doors that access the other worlds, nor was I able to put all maps into one, but I do think that creating these three maps helped me better analyze the text. In creating the maps, the texts were reduced to a few geographical places that most importantly represent Roland’s travels. It is, after all, the locations written about (as they tell stories themselves) which are the most important aspects of the novels. Siegert states, “the materiality of the map interferes with its contents, and as the medium of representation interferes with the representation of the territory, the map as a representation [of The Dark Tower series] is deterritorialized by the map as the medium” (16). Perhaps it was a blessing that the intricacy of this series forced me to create multiple maps in order to best represent the world described by King. Although these recreations separate the locations from their apparent flow, and are not exact representations of the text, it also allows the audience to understand the complexity of Stephen King’s creation.

Works Cited

“DEVL Design: March 2012.” DEVL Design: March 2012. N.p., Mar. 2012. Web. 20 Oct. 2013.

“Downtown Manhattan.” Google Maps. Google, n.d. Web. 20 Oct. 2013.

King, Stephen. Song of Susannah: The Dark Tower VI. New York: Signet, 2004. Print.

—. The Dark Tower: The Dark Tower VII. New York: Signet, 2004. Print.

—. The Drawing of the Three: The Dark Tower II. New York: Signet, 2003. Print.

—. The Gunslinger: The Dark Tower I. New York: Signet, 1982. Print.

—. The Waste Lands: The Dark Tower III. New York: Signet, 1991. Print.

—. Wizard and Glass: The Dark Tower IV. New York: Signet, 1997. Print.

—. Wolves of the Calla: The Dark Tower V. New York: Signet, 2003. Print.

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literacy History – 2”. New Left Review 26 (March-April 2004): 79-103.

Siegert, Bernhard. “The Map Is the Territory.” Radical Philosophy 169 (September/October 2011): 13-16.

“Welcome to StephenKing.com.” www.stephenking.com. Web. 20 Oct. 2013.

The post Probe: Mapping The Dark Tower Series appeared first on &.

]]>