The post Performance, video formats, and digital publication in a Latin American context appeared first on &.

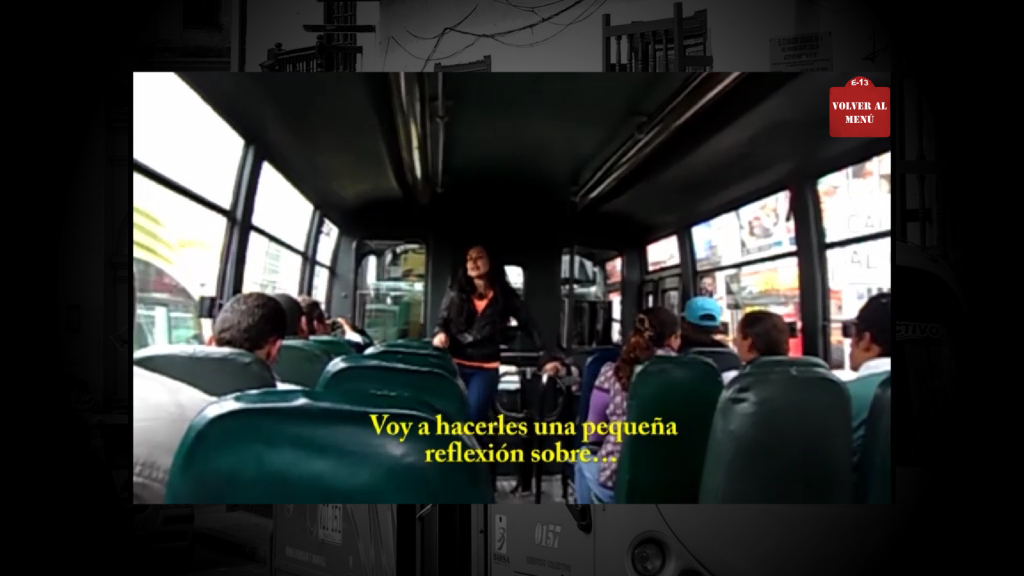

]]>Flaubert: 20 rutas consists of a series of performances made by Alejandra Jiménez in Colombia, where she delivered speeches based on texts by Gustave Flaubert to random users of the Bogotan public transport system. It is an intervention in the sense that it gets to an audience without it knowing or even wanting to experience such performance, rather than the audience consciously attending an artistic event. Also, if only haphazardly, it records the reactions of the public—sometimes they clapped at the end of the speech, sometimes they would remain silent, one lady would give her some flyers and information about God. Jiménez’s reflections on her performative interventions in her MFA dissertation (also called Flaubert: 20 rutas) seek to question the implications of transit and mobility in Colombia’s capital, as well as the replacement of old buses and busetas (small buses) by more modern models, the ways in which drivers used to appropriate their units and the advent of non-place-like environments in the new buses—cold, gray, almost antiseptic (Augé 2000; Jiménez 2013).

So Flaubert: 20 rutas is actually two works or, as I usually call them in this probe, two artistic products: the first one is a series of performances recorded in low-fi video—which is not just a byproduct of the performances but, as we will see, will take them to another sort of materiality. The second one is the research-creation dissertation defended by Jiménez at Universidad Nacional de Colombia (UNC). Given that the latter was already made public by the UNC web portal, the interest in the “publication” of Flaubert: 20 rutas was focused in the videos, since it recorded the reactions of the audiences randomly “formed” by Jiménez’s interventions on Bogotá’s buses and busetas, and therefore constituted a sort of “invitation to reflection” without recurring to academic rhetoric.

The videos, merged in F4V format, were gathered and displayed in a custom-made Adobe Flash Player application interface, made under Jiménez’s commission. Given that the only non-textual traces of the performance available for “publication” were the F4V files, the interface gave them a “database aspect”. All of the 20 performances are listed together in a 5 x 4 slot interface. Each slot is randomly numerated and identified with a distinctive title or topic: “Alcohol,” “History,” “Artists,” “Turning 30,” and so on. Recording the performances makes the project ambiguous in terms of function and materiality. As in the case of PDF, which reproduces paper in a digital environment (Gitelman 2011, 115), F4V is a digital file that mediates a video recording device, which in this case mediates in turn a time-bound artistic performance. It is the recording of the recording of the performance. But whereas a rose stops looking like a rose after several photocopies, in the videos the loss is both visual and aural, since not all the background details are clear or audible.

Before discussing video file formats as cultural artifacts in Latin America it would be good to give an overview of their proliferation and the process of standardization set forth by the ISO base media file format. Just as in the case of MP3 (Sterne 2006, 826), video files are called container or wrapper file formats, a sort of metafile which may be capable of storing multimedia data along with metadata for identification, classification, and reproduction purposes. Some container formats can be reproduced across different platforms. When I started downloading videos to play them on a computer, the most common file format for PCs was Microsoft’s AVI (Audio Video Interleaved), whereas Apple used QTFF (Quick Time File Format). Macromedia’s FLV (Flash Video) first appeared some years after AVI, and the interesting thing about FLV is that it supports streaming, making it easy to share, play and store in online digital environments, while it has a relatively small size, perfect for low-bandwidth internet technology. It became widely used by video streaming websites like YouTube and Reuters, but even before that Flash Player—Macromedia’s also small viewer application—was already popular after being integrated as a free plugin to the then famous Netscape internet browser. When Adobe bought Macromedia, in 2005, Flash Player was the most used multimedia player worldwide, either as an installed application or as a browser plugin, surpassing Quicktime, Java, RealPlayer, and Microsoft Media.

Despite FLV’s hype, when the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) came up with its base media file format, Quicktime’s QTFF was chosen as the base for standardization, probably because its potential components (audio, video, text for captioning, and metadata) were slotted in different “sub-containers”, which allows for edition and revision of specific parts without having to re-write all the information every time something is modified. From that moment, the authors of FLV have strongly encouraged users to switch to new container formats aligned with the ISO base media file format standards, such as MP4 for audio and F4V for multimedia.

Following the generalized call for standardization, the multimedia files for Flaubert: 20 rutas are encoded in F4V format. However, its quality makes it difficult to be uploaded to high-definition video websites supporting F4V, such as Vimeo, and it is more akin to low-fi environments like a great part of YouTube’s content. Although these videos are the registration of the core material for her research-creation project, the only published product so far has been the thesis dissertation. The videos allow for the ephemerality of the performance to be recontextualized in a digital environment, “micromaterialized” as proposed for the MP3 (Sterne 2006, 831-832) and therefore given a physical existence, however minute and encrypted it is. As in the initial functions given to gramophones (“storing”, so to say, the voices of people before they die), in Flaubert: 20 rutas the recording and digitizing of the performances made by Jiménez in the Bogotan public transportation system is a prime example of how to promote critical thinking out of creative events, while at the same time trying to overcome the temporal restrictions embedded in artistic practices such as music, sound art, and performance.

This probe will now raise some questions about the “publication” of the videos and its accompanying Flash Wave interface in a Latin American context. By “publication” I mean the public release of cultural artifacts through a mediation system, such as a publishing house. The work of mediation agents, such as editors and curators, has been widely analyzed by authors like Pierre Bourdieu as being fundamental for the acknowledgement of value and importance of cultural objects within capitalistic societies. Bourdieu asks who “authorizes the author” (2010, 156) in order to address how mediation agents (known in media studies as “gatekeepers”, see Shuker 2005, 117) deny the economic value of the cultural objects they promote and in so doing they “bet” for their potential symbolic value for a determined audience in a given artistic field. Without such “bets”, external and peripheral to their creative work, artists are arguably less visible in the artistic fields (Bourdieu, 2010).

Now, this is one way of seeing it. Clearly, publishing houses and galleries are nothing without artistic products. It is the commodity they commercialize. But the articulation of independent publishing collectives has the capacity to disrupt these hierarchical types of mediation. In the case of Flaubert: 20 rutas, the initial interface for the videos (see image below) was made by a Colombian programmer, whereas some arrangements have to be done by the programmer who will upload and maintain the site (designated by the publishing collective). Extra menus will be added in each “route” to increase the navigability experience and include complementary material—either transcriptions, critical reflections, or other related creative texts. A “shuffle” or random playing function, conceived by the first programmer but not given a visual interface, will be finally installed.

As I have suggested, one of the most interesting aspects these videos show is the difficulty to realize a performative intervention such as the one proposed by Jiménez. Randomness, which is at the very core of the creative process through the choosing of a determinate bus/audience, is reproduced or enacted several times throughout the project (the non-sequential numbering of the clusters, the “shuffle” function, and so on). In that sense, the idea of distributing Flaubert: 20 rutas for an ideally greater audience through the creation of a website interface seems to be in contradiction with the ephemerality that permeates the idea of this performance—and of performativity in general.

My concerns about the publication of this project in a Latin American context have to do mainly with functionality and accessibility. In Mexico, Colombia, and presumably in the rest of Latin America it is not common to have Flash Player installed as an application, but rather as an internet browser’s plugin. This means, on the one hand, that FLV is generally used only when accessed through streaming via YouTube or similar websites, and on the other that platform-specific formats like AVI are preferred when storing videos in a hard drive. Jiménez had the initial project of supplementing a CD with the digitized version of the videos with a FlashWave interface, which nevertheless restricted its playability to PC and impeded to play it as a DVD or VideoCD format. To understand why discussing format presentation is so important in a Latin American context, it is important to note that neither video disc players nor personal computers are commodities shared by all of the Latin American populations.

How different is the gatekeeper’s work from that of an artist uploading her/his videos on YouTube and somehow building a visualization interface for them, perhaps using predetermined template websites like Wix? The bourgeois bohemian sacralization of the artist as dedicated solely to the creative process, without being involved in the “dirty job” of getting an audience for it (Bourdieu 2010, 158), is highly responsible for the importance of mediation agents in the artistic fields. But rather than seeing mediation systems as opportunistic niches for the commodification of artistic objects, independent publishing collectives propose collaboration as a means to de-articulate the power hierarchies inherent in the work of mediation (here I’m using “work” in the same way Stuart Halls uses it in The work of interpretation, that is, as an effect exercised and set into action by mediation–the work mediation that “makes” upon its components). In that sense, most of the designing part was already done when it got to the hands of the independent publishing collective. The work of the next designer is for adaptability to the internet and “maintenance”, so to say. As they say in the editorial profession, “Everything is perfectible.” This does not mean the collective had inverted (either in economical or symbolic ways) so much as it could have if the author had not commissioned the creation of the digital interface beforehand. But it is exactly this focus on the mechanism of collaboration that can rather potentially offer a wider audience for a work that was buried under academic and temporal barriers. Of course, that does not prevent the publishing collective from adding its logo on the displaying menu, as there is in the end a collective “inversion” in the artistic product. Are the underlying structures of mediation questioned through this type of collaborative project? I do not totally think so, but I consider that it poses a working methodology open to the possibility of such questionings. What are publishing houses, then? Hubs full of nodes or links. Networks connecting to other networks connecting to other networks.

However, it is important to remember that in Latin America (and also in any other place touched by globalization), access to mediation systems is transversally restricted in terms of class/income, race, and gender. Any decision to use a technological device to transmit artistic media is therefore biased from its very conception. The practical objective becomes more fundamental than the ethical one: the technology with the biggest audience potential wins, and that is of course internet. Discs are in the process of becoming fully obsolete, just as 8-track cartridges, cassettes, and laser discs. But internet does not assure a durability of the database. The underside of internet is its potential for ephemerality. The hosting site can expire and not be renewed, and the database would be lost, if it is not lucky enough to be recorded by a database like the Internet Archive. So the “triumph over ephemerality” is probably delusional, while the supposed release of an artistic object to a wide audience is biased in transversally oriented levels.

References

Augé, M. (2000). Los no lugares. Una antropología de la sobremodernidad. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Bourdieu, P. (2010). El sentido social del gusto. Elementos para una sociología de la cultura. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI Editores.

Gitelman, L. (2014). “Near print and beyond paper: knowing by *.PDF.” Paper Knowledge: Toward A Media History of Documents. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 111-135.

Jiménez, A. (2013). Flaubert: 20 rutas. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia. MFA Thesis.

Shuker, R. (2005). Popular Music. The Key Concepts. London/New York: Routledge.

Sterne, J. (2006). “The mp3 as cultural artifact.” New Media & Society, 8 (5), 825-842.

The post Performance, video formats, and digital publication in a Latin American context appeared first on &.

]]>The post A Digital Poetry Writer: Yaxkin Melchy and Lisa Gitelman appeared first on &.

]]>

Web writing or moving our works on the internet means never relinquishing while there exists this universe of expressions that appear and disappear, that are created and erased. The web is a riddle to write.

(Melchy 2011, 35).

The subtitle of this chapter from Lisa Gitelman’s book Paper Knowledge attracted my attention since I skimmed through the semester readings–knowing by PDF. When you get most of your semester’s readings on a USB or a Dropbox file, as has mostly been my case since my M.A. years in Tijuana, you eventually get to understand how stupid it is to print 100 pages one week and totally dismiss them next week until the end of semester (at best). Plus, digging into the thousands of photocopies left behind to reread an interesting passage can become like finding a needle in a haystack. So you give up trying to materialize your readings and start reading them as you should’ve done in the first place–on your computer screen. Or e-reader, or tablet. Suit yourself. The thing is, if you really like reading, most of your material will eventually be in PDF format. Increasingly. I know many colleagues and friends still stand for the books’ materiality (such romantic, pseudo-bohemian aspects like “the smell of a good old book” or “the feeling of the pages in my fingers when I turn them”), but sometimes the only way to get access to some texts, in a world of urgency and saturation, is through digital formats, mostly HTML and PDF. We get access to important portions of knowledge through texts that do not have a material coalescence.

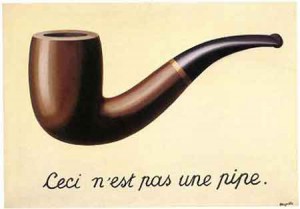

It is interesting that Gitelman starts her arguments by invoking the meta-representational dilemma posed by Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe, later studied by Michel Foucault, which uncovers the artistic process of mimesis as a representation that wishes to take the object’s place, but leaves an absence instead, a kind of ghostly presence which is probably related to Walter Benjamin’s concept of “aura”, that non-reproductible, almost divine feature of original paintings that mechanical copies would not attain. Benjamin would not have thought that aura would then move to previously non-aural artistic processes, such as traditional photography when digital photography came to replace it, or from obsolete music players and video game consoles. In the middle of the discussion about PDFs “page images” (as defined by Gitelman 2011, 115) resembling print pages while not entirely being such (becuase of the lack of materiality, its most important feature), the auratic argument is one of the main positions at stake.

Here’s where the task of writers who release (I find this verb mor accurate than “publish”) their works online gets into the stage. There are hubs of writers, like the Alt Lit movement in US (using this contested term to refer to blogs such as Pop Serial and New Wave Vomit) or the “Savage Poet Network” blog in Mexico, who in a way have given up their right to get an economic profit for their writing. Most of them have published their work under alternative licenses, such as Copyleft and Creative Commons. I know this is quite a deal for people in Quebec, for example, where the writer unions and associations have struggled for the aknolwedgment and rights to be paid for their creative work, but it also poses a different approach to the possibilities of network publishing.

I believe that poetry read on paper drags a History of literature and a body that is the material itself–the history of that paper. Poetry on screens is not better or worse, it has another form and other ways or entries for us to perceive the poetic, we’re talking about interactions like Internet allowing us to have access through a screen to contents that otherwise would be almost impossible to read due to its historical or geographic distance (Melchy 2011, 34).

Yaxkin is, as his Australian translator Alice Whitmore calls him, “a young self-published Mexican poet and founding member of the Red de los poetas salvajes [Savage Poets Network]” (Whitmore 2013, 42). In fact, Yaxkin is the brain and hand behind the Network. He invited several poets to publish their works online, then created projects such as anthologies and compilations, so that “the Red began as a small-scale blog and eventually transmogrifed into a vast, unoffcial online journal and forum” (Whitmore 2013, 43). He did this as an alternative to Santa Muerte Cartonera, a project he was holding at that time (2008) with the Chilean poet Héctor Hernández Montecinos, one of the first independent publishing houses to use cardboard as primer material for the creation of their covers (known as the Cartonera movement; for more information see Akademia cartonera, a primer of Latin American cartonera publishers published by U Wisconsin-Madison). Given the strong emphasis of materiality in the cartonera projects, instead of proposing a sort of “digital cartonera”, Yaxkin decided to apply both the digital and the material sides of publishing in the Red, since many books were published both in digital format and as chap books or in paperbound editions. Later on he would keep on mixing digital and printed media in his project 2.0.1.3. editorial.

The ambiguous nature of PDF (one would say its “simulacre”, following Baudrillard, rather than its “nature”) is akin to the amphibious strategy of Melchy’s project. When published in PDF viewing sites, such as Issuu, the experience of reading is even simulated by a page-flipping sound and flashing page corners to suggest movement. The PDF is like the sample in a virtual store, and the ideal paper sample keeps on being the one to have (at least when it’s not “grey literature”), even if the PDF version is stored in our computer and can be readily printed. We can see that the ungraspable, almost ghostly presence that Gitelman grants to PDFs is not fully realized in digital projects like this. Even though Melchy mentions the commonplace of multimediality as a possibility within the digital (“Poetry read on computers can be accompanied with video, audio, interactivity and even immediate feedback”, Melchy 2011, 35), there are no audiovisual contents in the Red’s PDFs, but in the blog itself instead. In this sense seems to be true that ” The portable document format thus represents a specifc “remedial” point of contact between old media and new” (Gitelman 2014, 115). The ground is there for the taking, but the users have only dealed with a limited number of possibilities, still dominated by the printed page format.

Within Yaxkin’s work there is a twist on the audience intended, though. The use of such simple apps as Nick Ciske’s Bynary to “read” binary code fragments included in Poesíavida will reveal us a multi-level reading process, in which not all the content is intended for human eyes. Some of Yaxkin’s work is only “readable” by machines, which doesn’t mean such machines will interpret such readings, just load them and (if asked for) display them. However, how far are we really from digital poetry?

There are things I don’t share with Gitelman’s approcach. For example, she says that in the PDF technology there is an orientation toward the author rather than the reader” (Gitelman 2014, 124). Even free PDF-reading programs, such as Foxit, have already integrated editing, commenting and fill-in tools, let alone the Canadian Government PDFs that generate a barcode when properly written on. So even in the rigid form of PDF, there are many ways to distort the text, as it was the case with printed pages, to add and erase things, to include commentaries. And in the end the file is never the same, even so when the program asks us to save the changes before closing the document. However, it is undeniable that PDF won over other text files because of its “natural” tendency to lock text editing while allowing (within certain limits) text copying. This is why web publishing sites like Issuu are so popular among comercial firms, but also among independent publishers. It gives an impression of materiality, with all those stacks, shelves and bookmarks. A virtual library potentially full either of grey literature or of avant garde experiments on readability in a post-print era. Hmmm.

References

Gitelman, Lisa. “Near print and beyond paper: knowing by *.PDF”. Paper Knowledge: Toward A Media History of Documents. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2014, 111-135.

Melchy, Yaxkin. Poesíavida. Tijuana: Kodama Cartonera, 2011.

Whitmore, Alice. “Four Poems by Yaxkin Melchy”. The AALITRA Review: A Journal of Literary Translation, Melbourne: Monash University, No.6, 2013, 42-55.

The post A Digital Poetry Writer: Yaxkin Melchy and Lisa Gitelman appeared first on &.

]]>The post “Intellectually Knowable Lines” – UltraModern Nostalgic Inscription and Other Spatialities, an Exercise in Dirty Scholarship appeared first on &.

]]>In an effort to unpack the notion of the Chinese typewriter as emblematic of an unassailably perverse difference in ontological positioning, it is essential to consider the manner in which the threat that the typewriter represents is situated (where, in other words, the discourse machine-gun is pointing). Rather than simply limit the Chinese typewriter’s cultural significance to its representation of the Other by the adoption and adaptation of processes typically considered Western/normative, the artefact is here taken as a cultural object so thoroughly Othered, not due to its foreign composition, but because it threatens to accomplish the collapse of “Occident” and “Orient” that Said imagines and hopes for (Said 28). The popular conception of a Chinese typewriter as an overly complex, if not physically overwhelming, device (Mullaney) suggests a fundamental and persistent failure to acknowledge Chinese scribal/linguistic expression as possessing a coherent logical structure which demands appropriate technologies of inscription. From an Occidental (Orientalist) perspective, the problem of the Chinese typewriter is simply that its purpose – efficient, standardised inscription – is at odds with what is understood to be the structure native to Chinese languages, and that this disparity suggests a profound failure in inventive logic, producing “curiosities at best and absurdities at worst” (Mullaney). The supposition is that the most effective iteration of a Chinese typewriter would be a machine that is linguistically conservative and accurate, with a key-tray so massive that it threatens to tip the device into absurdity. (If we were to subject the English typewriter to similar scrutiny we might well ask, “Where is the yogh-key? The thorne?”)

Failing to acknowledge various attempts to parse-down Chinese typing suggests an effort to characterise Chinese thought as always-already compromised, overwhelmingly antiquated. Concerns similar to those of Orientalists arise in considering the typewriter from a vantage point less concerned with maintaining “flexible positional superiority” (Said 8), although with a less fatalistic outcome. From the inventor’s perspective, the effort to condense, synthesise, and (re)organise a complex ideogrammatic language might have less to do with questions of linguistic or cultural authenticity/purity as with the mechanical problem of joining an organic group of ideograms with a technology whose inception subdivides the page following grid-logic and demands that each character occupy a uniform space. Indeed, the “brilliance of the solutions devised” (Mullaney) points towards a complexity of thought countering the facile presentation of the Chinese typewriter in Occidental (pop)media (Mullaney). Following from Said’s affirmation that Orientalism functions through “[…] a distribution of geopolitical awareness into aesthetic, scholarly, economic, sociological, historical, and philological texts […]” (Said 12), here the Chinese typewriter will be taken as a machinic metonymic expression of Orientalist impulses “extend[ed …] to geography” (5), in considering ties between the typewriter and urban planning practices of the early/mid twentieth century.

This gesture of comparing the machine to the places of its use takes the object and its surrounding geographies as complementary material “texts”, and attempts to map their “referential power” in what Said identifies as a strategic formation (20). Admittedly, the process commits a certain anachronistic violence, as over two decades separate the two maps, yet the object of this consideration is to nuance contextual understanding of the typewriter, rather than account fully for the formation of urban centers…

When juxtaposed, the maps of Milwaukee and Shanghai here presented demonstrate the manner in which the Modern grid-network of city streets might be implemented with varying degrees of success; Milwaukee is relentlessly formal in its attention to grid networks, quelling even the occasional curved road in favour of bisecting diagonals, Shanghai, alternatively, demonstrates a much less rigid road system, still using a grid-overlay, but fitting strict angles to pre-existent curves. One of the more noteworthy details on the map of Shanghai is the disparity, in the image’s center, between the (historically) British/Occidental enclaves and, to the south, the “Chinese City”. The Occidental here, as in Milwaukee, endeavours to hold-fast to a formal grid, while the Oriental resists this, most forcibly in the ring-road which attracts the map-reader’s eye. Again, while this may be taken as a hesitancy to fully implement modern planning and constructive techniques to their fullest, it might also be cast as a mediation of those methods, a softening of that logic to account for pre-existent structures. While the rationale behind such a symbiotic mode of urban organisation is not readily apparent (ranging from practical concerns such as infrastructure and the costliness of construction, to questions of aesthetics, to simple conservatism), it acknowledges the existence of various sites and spaces, rather than reducing the entire spread of urban spaces to a single grid.

Similarly, the Chinese typewriter does not operate following the impression/assemblage process of the direct key-to-(gridded)page system of its English correlative, complicating the grid formation not only in the marking of the page, but the marks themselves (the complex and combinatory nature of Chinese ideograms renders the basic, single-stroke uniformity of glyphs problematic). Instead of a device designed to navigate a strictly defined grid, the Chinese typewriter featured either a tray of selectable typeface or a seventy-two key system which could produce thousands of Chinese characters (Mullaney). Both formulations of the Chinese typewriter attempt to mechanise a writing process with the awareness that the machine itself will, in all probability, be incapable of encompassing all the nuances of that process’ language – the only positive formulation of this awareness is to foreground the potential of the Chinese typewriter to function within set parameters, within specialised conditions. It is this last point, that the Chinese typewriter is not inadequate, but rather configured to work within constraints, that demonstrates not only its appropriation by adaptation (launching the typewriter into another linguistic context), but also that the Chinese typewriter might be justifiably characterised as a “better” inscription device – reserved for the sorts of writing that a machinic process might be useful for…

The Chinese typewriter, then, threatens to undermine, if not destroy, the conception of a superlatively modern West in demonstrating the failure of bureaucratic technologic to adaptively re-configure itself, or provide tools commensurate for (exclusively) bureaucratic work. The ability of the Chinese typewriter to transpose an ancient scribal system into a new machinic iteration suggests a sort of ultramodern nostalgia that denounces the naïve Occidental assumption of unidirectional progress that serves as the impetus for the development of “new” processes of inscription.

Works Cited

Mullaney, Thomas. “The Chinese Typewriter.” China Beat. 5/14/2009.

http://thechinabeat.blogspot.ca/2009/05/chinese-typewriter.html. Accessed 14 November 2012.

Said, Edward. “Introduction.” Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1978. 1-28.

Map Images: Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin.

http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/. Accessed 16 November 2012.

— Christopher Chaban

The post “Intellectually Knowable Lines” – UltraModern Nostalgic Inscription and Other Spatialities, an Exercise in Dirty Scholarship appeared first on &.

]]>The post Geisha Bride with Remington Typewriter appeared first on &.

]]>Since the obsession with the Orient began, western civilization has created many misconceptions about the culture it has worked so hard to imitate. Edward Said describes the Orient as “an integral part of European material civilization and culture” (2), as it not only expresses but also represents a cultural and ideological mode of discourse. Said’s description helps better convey the desire for European society to immerse itself in what it perceives the Orient to be, primarily as it appears in art and other more eclectic images, but nothing deeper. Despite their desire to bring the Orient into their homes, western society had developed a false ideology of Orientalism, feeling that it was “essentially an idea or a creation with no corresponding reality” (5). This western ignorance of the Orient can be attributed to a superiority complex that the west felt it held over eastern cultures.

Whether many members of the western world were aware of it or not, the overall purpose of this superiority complex was for western culture to maintain dominance over the orient. In order continue this domination, the west feigned ignorance to the deeper essence of eastern customs and culture and instead focused on the shallower more esthetically pleasing aspects of the culture to imitate. This idea is further extrapolated as Said suggests, “Orientalism is more particularly valuable as a sign of European-Atlantic power over the Orient than it is as a veridic discourse about the Orient (which is what, in its academic or scholarly form, it claims to be)” (6). Western civilization found itself more powerful by meticulously picking and choosing what parts of the Orient made its way into fashionable European society. This theme continued as the western focus shifted through different areas of the orient; earlier imitations reflected Egyptian and Persian styles, which gave way to a more Indian focused period. Most recently, the Orient has come to refer to the Asian Orient including areas such as China, Japan, North and South Korea, etc. Given that this is western civilization’s most current obsession with “Oriental culture” I find that the image below shows how little we have budged from our original misguided notions of the Orient.

The photo is titled, “Geisha Bride with Remington Typewriter”. By introducing the official label of the Geisha in the title, the artist evokes certain implications about the figure we then see. The first immediate and obvious difference that is apparent is the fact that Geishas are women of Japanese culture whose dedication to the art of performance is their being. The “Geisha” depicted in the photo, however, is very clearly Caucasian with little to no identifying Geisha markings. The cultural difference is most apparent in her unruly blonde hair. The Geisha customs expresses the pains taken to perfect and maintain the Geisha’s hair with intricate styles often professionally done. The woman in the photo appears to have purposely teased her hair into chaos, the exact opposite goal of a Geisha’s design. It is also important to note the dress being worn by the “Geisha” in the photo. As she is labeled the “Geisha Bride”, it is apparent that the photographer decided to westernize the Geisha by placing her in a traditional European-American wedding dress. In respect to the orient, there are a many concerns with this choice. Although Geishas could marry, they had to retire from their profession first, as active Geishas are expected to be single women for the sakes of the clients. Additionally, a Geisha would traditionally wear the kimono with an obi sash as their uniform. Although white may mean purity, oftentimes in oriental culture, white is the color that represents the act of mourning.

If aware of the lack in cultural respect often found in western depiction of the orient, the photographer could be mocking the idea of western ignorance, or perhaps is representing a marriage of oriental customs to the western culture. The bride is wearing traditional geisha makeup as her face is coated white with only parts of the lips painted. Her deliberate eye makeup also gives the appearance of a mask as is the Geisha custom. Despite this one key identifying mark of Geisha custom, as the viewer moves away from her face, the rest of her body moves further and further away from oriental tradition, as is seen with her hair and dress. She is positioned behind the Remington, with her arms around the typewriter, as if she is marrying the machine. The Remington is another symbol of western power – another deliberate choice over a Chinese or Japanese typewriter, as may have been more suitable for the Japanese culture.

By placing an American typewriter versus one of an oriental style, the photographer shows the western dominance over this cultural symbol of oriental society, so much so that she is westernized herself. There is also no ring on the bride’s finger. Also she is looking up with her eyes wide open, as if someone was going to take the typewriter away from her. It is also important to note that if there was a Japanese or even Chinese typewriter (a much more complicated machine that takes much more time to master than the American style) in this image, the typewriter would be massive and probably have to take up most of the image, compared to the American Remington that the photographer has chosen. Since the woman getting married in this image looks to be more “Americanized” by the photographer (as shown with her hair, eyes, and dress) rather than a true Japanese Geisha, perhaps it does make more sense for the photographer to use the standard American Remington typewriter as well. As the western world has shown for many decades of oriental interest, it appears to care little for the underlying facts and details surrounding the culture and more focused on the surface image that the Geisha and Remington evoke as one object. We may either praise the photographer for recognizing the clash of the two cultures, or as critics we may continue to see an ignorant portrayal of a culture the west has spent over a hundred years dominating as though the Orient were a toy.

Works Cited

The Antikey Chop Typewriter Blog.” The Antikey Chop Typewriter Blog. Tumblr, 12 Oct. 2012. Web. 12 Nov. 2012. http://theantikeychop.tumblr.com/post/33569344656/geisha-bride-with-remington-typewriter-the.

Said, Edward. “Introduction.” Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1978. 1-28

— Emilie Arsenault

The post Geisha Bride with Remington Typewriter appeared first on &.

]]>The post Typewriter-Grrrls: Type-writing, Fashion, and Cyborg Apocalypse appeared first on &.

]]>

From: “How to Type – By the Touch System”, published by the Toronto Printing Plant of Underwood Elliott Fisher

Demonstrating Gender

Navigating gender/gendered discourse in the context of typewriter history is problematised by the extreme degree of uncertainty and ambiguity which prevents any neat demarcation of the subject. We might hurtle down several (roughly) parallel paths, considering a history of gendered writing (Kittler 186), of gender-coding machines (Keep 405), of the variance between popular representation and lived experience (Keep 410), or of shifts in the labourer’s access to the processes of production (Gitelman 206). Moreover, as emphasised repeatedly (Gitelman 208; Keep 405; Kittler 183), a slippage occurs from the very onset of any investigation into “typewriters”: do we mean the machine or the operator? The two cannot exist in isolation – the machine cannot operate itself, and being a typist is predicated on working “with” a typing-machine (c.f. Heidegger, in Kittler, 198). Thus, unpacking how gender operates with and around typewriting must necessarily begin with an admission that the familiar male/female binary is already mechanically complicated.

Identifying the typist as a “new species”, with a sort of “natural destiny” (Kipling, in Keep 401), complicates reading the typewriter as an emergent feminist by joining the bodily (female) and the machine (typewriter); efforts to categorise, understand, and demark the limits of the typewriter all point towards the typewriter’s role as transformative (Gitelman 185), transgressive, and nebulous. The role of the gaze (in relation, variously, to the machine, workers/work-space, and mass media), is paramount: “the fear and fascination” (Keep 401) about identifying the female as feminine, rather than unsexed (402), or mechanical (Gitelman 203, 208), was assuaged, in large part, through visual confirmation/creation of the type-writer girl as profoundly (if not pornographically) corporeal, human.

Despite the gaze and attempted control of hegemonic patriarchy, the typewriter was yet able to “[resist…] subjection” (Keep 418) and literally work “from within the structure of exploitation” (420) – particularly in remaining “in constant flux” (419), being both visible and viewing, mechanical and sensuous, and resisting an easily identifiable (and thereby controllable) subjectivity. The most dangerous position for the typewriter is one of repose – “becoming” (ibid.) “with” the machine, and casting off the antiquated conception of the female as having “limited physical resources” (402) allows for a freer subjectivity. One mode of achieving this floating subjectivity is in maintaining the initial, fundamental ambiguity in “typewriter” – we mean to stray into the realm of the post-human, to sustain a (pre-electric) cyborg-process, to be the machine and the operator!

Liminality, Touch-Typing, and Positioning the Typewriter

In considering the visual dynamics of typewriting, two distinct economies of gaze are readily identifiable: that of the body of text produced (by means of a visible or invisible inscription process), and the scopophilia in watching the typist. Relevant to both of these foci is the positioning of the typist’s body proper, with attendant implications of desire, both for economic efficiency (in the case of concrete typed copy) and, more humanly physical, the employer’s desire of the typist herself. In both cases, the typewriter hovers between granting clear images, providing visual confirmation of (re)productivity, and maintaining non-visual/non-physical (mechanical) process. Here, Lisa Gitelman’s formulation of the upstrike typewriter as a “black box” (Gitelman 204) is useful, taking the device as “not a public or a human matter, only a secretarial and technological one” (ibid.); the typewriter is at once private, mysterious, and profoundly industrial – in its adjectival signification “secretary” is rendered mechanical. As with Twain’s typesetter who “composed as he composed” (ibid.), the typewriter typewrites… And yet, the black box is not without a certain appeal, its own “seductive enigma” (Keep 401), maintain by obscuring processes (the real) enough to be suggestive, tantalising.

The sensuality of the typewriter is so pronounced, so inextricable from the any mention of the technology, that the machine itself becomes invested with a “new”, potentially unsettling, cyborg-allure. Typewriters(’)/bodies were never free from scrutiny and control – when not observed they self regulated, with body, body type, and fashion dictating their successful entry into and negotiation of the workplace (see Keep, throughout, but especially 404-405, 410; Gitelman 207, 211-212). This is, in fact, in keeping with the assertion that “media is message” – rather than obsess over what is arguably peripheral (the operator’s sartorial deportment), aesthetics takes a turn towards the (non-human) technologic.

This move towards the beauty of the machine is manifest in cover image of the above Underwood pamphlet: being the cover to a brief practical manual on touch-typing, the only suggestion of anything organic, much less human, in the image is the decorative (and, it should be noted, useless) ribbon in the cover’s lower right quadrant. Juxtaposed with the “objective” photographic reproduction of the Underwood typewriter, the hand-drawn ribbon, coupled with the skewed angle of the “card” which it superimposes, softens the manual’s presentation, suggesting that the “black box” which looms in the background can be rendered a touch less daunting. However, this does not connote any precedence being granted to the human operator; indeed, the pamphlet devotes its first sections to a schematic of the device, subsequent to which, the human-typewriter may be addressed. When the human does enter into the manual, it is in a shape subservient to the machine (see Figure 1, above), placed to promote efficient production, and accuracy when working the keys. That which is stereotypically identified as sensuous (the typist) is here transformed into the profoundly sensible, placing the limbs not to stimulate human response, but to kinetically translate energy into the smooth functioning of machined parts. Similarly, there exists an unresolved binary complication on the cover of the Royal Typewriter Company’s user’s manual for the “Gray Magic” typewriter:

Cover to the user’s manual for the Gray Magic (Quiet De Luxe) Portable Typewriter, Royal Typewriter Company. Circa 1949.

Notwithstanding the attempt at visual subterfuge in the richly coloured background of the pamphlet’s cover, and the effort made to add a sense of chromic brilliance to the words “Gray Magic”, the machine itself remains mercilessly matte gray. How then, would this machine’s practical metal casing interact with its operator’s potential desire to appear distinguished, stylish? Would investment in a (not-too-intrusive) desk bibelot or nattily put together suit provide the balm for the bland aesthetics of the machine proper, or were the two more mutually reinforcing, with the machine throwing the typewriter’s own attractiveness into sharper relief (inviting the male gaze only to reject it in favour to ministering to the machine)? What, moreover, of the purported impulse to “wear “rational” dress” (Keep 407)?

With this last query, we return to the Underwood touch-typing manual, more specifically, the brief notations made on the booklet’s back:

Inscribed, rather ironically, in pencil, are a series of measurements (bust, waist, hips, and lengths) for a set of woman’s clothing. While it is impossible to directly relate this “markup” (see Andrew Stauffer’s work with nineteenth century marginalia) with typewriting, that a typewriting manual be at hand, and deemed an acceptable surface upon which couture might be inscribed reinforces a reading of the typewriter as always-already in flux, perforating and changing female subjectivity at all levels…

Works Cited

Gitelman, Lisa. “Automatic Writing.” Scripts, Grooves, and Writing Machines: Representing Technology in the Edison Era. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999.

Keep, Christopher. “The Cultural Work of the Type-Writer Girl.” Victorian Studies 40.3 (Spring 1997): 401-427.

Kittler, Friedrich. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. [1986] Trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz. Writing Science. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999.

— Christopher Chaban

The post Typewriter-Grrrls: Type-writing, Fashion, and Cyborg Apocalypse appeared first on &.

]]>The post Typewriter/Piano, Poet/Composer appeared first on &.

]]>

The orchestral piece “Briony,” part of the score composed by Dario Marianelli for the 2007 film adaptation of Ian McEwan’s Atonement, is fundamentally a recent addition to the cultural landscape of typewriting. Despite its recency, the piece at its core makes a large-scale, conscious return to the “basics” of early media theory, fusing together classical music and the typewriter in a way which Marshall McLuhan had already conceived of much earlier. McLuhan’s early theories on the materiality of media, specifically from the essay “The Typewriter: Into the Age of the Iron Whim,” make a claim for the inherent connection between music and typewriting, both of which McLuhan consider to be intrinsic acts of composition that share more similarities than they might appear to at first glance.

If poetry – most explicitly in its oral form – manipulates timing, breath, suspension and syllabic rhythm to enhance the experience of both writing and reading a poem, music certainly does the same for any given composition. As McLuhan points out, Charles Olson and other mid-to-late twentieth-century poets employed vers libre to revert the state of language back to the original spoken, unrestrained circumstance of natural speech. If one agrees with Hemingway’s summing-up of the act of writing being as simple as one having to “sit down at a typewriter and bleed,” the poet becomes more like Sammy Davis Jr. than Samuel Johnson in front of his Remington. Indeed, the now-classic “Typewriter Song” by Leroy Anderson embodies the jazzy, uncontrolled essence of the connection between typewriting and music, tying in McLuhan’s and Olson’s conceptions of free verse and the typewriter as the frantic yet most honest means of writing (or “bleeding”) poetry.

However, “Briony” is not jazz, and is not a product of the cultural environment of the mid twentieth-century which, in truth, begged for a sense of freedom and escape from constraints of (largely) any kind. “Briony,” like most classical music pieces, is a deeply calculated, controlled composition which begs for a fixed and finite interpretation on the part of the listener. The piece begins primarily with interweaving notes of a typewriter and a piano. From the outset, the connection between the typewriter and the piano is established (or at least alluded to), consciously or not, by the composer.

Again, if we return back to the “basics” of the theory of writing, it becomes apparent that both acts have fundamental implications which cannot be ignored. As Vilem Flusser points out in “The Gesture of Writing,” the seeming banality of certain details regarding the gestures of written composition become more important in a larger epistemological framework. As such, beneath the banal and the undervalued lies the deeply relevant in terms of our social consciousness and, without returning to the rudimentary, it is nearly impossible to truly comprehend that social consciousness which we assume to be straightforward on a daily basis.

Flusser asserts that writing, in its most primitive and original form, is essentially a scratching or engraving with one material onto another. Though we may have lost or come quite far from the original gesture of writing as engraving, it may be that – if one looks closely – the gesture is still deeply present. In piano-playing the keys imprint, engrave or strike (though not materially or permanently, as the typewriter does) their strings, creating a particular sound which recreates the gesture of writing through musical notation. At the striking of both sets of keys sound is produced and rhythm is established. Both the piano and the typewriter involve the use of hands and fingers extended forward and rested above the keys of each respective instrument, uniting the tactile and sonic human faculties. Posture, and the way that a person places themselves in front of both the typewriter and the piano is extremely similar: both require a formal, rigid positioning of the body. As any first lesson in piano-playing will begin with posture, most early typewriter instruction manuals will dedicate an entire section to describing the ideal body positions for working on a typewriter. More complexly, however, both acts engage the mind in a linear fashion (quite literally, both instruments’ keys are arranged in ordered lines), have trained the mind to use all ten fingers rather than a fist or closed single hand, have given rise to a thought-process which functions in terms of linearity and progression, and have created a deeper connection in which the machine becomes essentially an extension of the physical human form.

What implications does this have on a social, and even on an anthropological, level? What does it mean when the introduction of the typewriter began to affect, modify and transform the way the human body physically interacts with it? Can our physical bodies actually be adjustable according to the materiality of our media?

Of course, it may be that “Briony” employs typewriter sounds in its musical score because Atonement deals largely with writing as a centralized theme within the context of its plot. Still, the continuity between the typewriter and the piano cannot be denied outright, even if the philosophical discourses of McLuhan or Flusser are ignored. To be sure, the continuity between the two goes beyond the fact that both instruments create sound.

On the basis of mood and atmosphere alone, the monotone, hard-sounding “click” of the typewriter’s keys seems to fit perfectly with the haunting, poignant nature of the film’s classical score. Indeed, the music is not only complemented but is accentuated and heightened by the typewriter sounds, adding an element of intensity that, nearly bass-drum-like in its steady rhythm, seems to resemble a death-knell sounding ominously in the background. The “scratching” Flusser associates with early writing has a sense of violence to it that seems to be translated to the typewriter, and by extension, to “Briony.” Why might this be the case? Do we inherently associate typewriting with a seriousness, coldness, monotony and rigidity that seem to shine through with “Briony”? If the gesture of writing, an equally solitary, solipsistic and serious-natured endeavor in itself, is associated with the typewriter throughout the majority of the twentieth century, does the typewriter have some inherently-associated emotional capital which marks our perspective of writing and typewriting? Might the composer be suggesting that the dichotomy between our forms of media continuously leaves ghosts of an abandoned media haunting and impacting our social consciousness? Finally, have we transitioned from the perspective of the jazzy, upbeat connotations of the typewriter which Leroy Anderson’s music seemed to propose toward one of the typewriter as inherently ominous and haunting as proposed in “Briony”?

— Stefano Faustini

The post Typewriter/Piano, Poet/Composer appeared first on &.

]]>The post PSYCHODIGITAL HYPERTYPEWRITER appeared first on &.

]]>Analog or digital? Fingers or digits?

When NEO rings a bell, do you RETURN or ENTER?

Is the Final Frontier, or the Pen-Ultimate?

Writing with-out a page? Will this save autonomy from automation, belt chastity from rhythmic autofeedback excess?

Or…did you not see this as the impetus for a radicalized aesthetic practice?

Predating the release of the iPad in 2010 and the popularization of the tablet computer as hyperportable alternative to the laptop, NEO is neither tablet nor laptop but an obscure Other option of portable computer monocultured for writing in the same way the e-reader is for reading. Quite simply, it’s the severed writing appendage of the desktop computer, resurrected autonomous.

Strictly speaking, NEO isn’t a “digital typewriter.” For that, one would better refer to an Underwood USB typewriter (1, 2), the iTypewriter, or perhaps even a laptop running ClickKey (software that maps typewriter sounds to keystrokes). But this is precisely why NEO is striking: though not a typewriter, cultural memory—especially when the avatar of the target demographic is a Boomer-aged rustic—cannot but associate it with one.

For we tend to think of the typewriter teleologically, as a stand-alone keyboard just waiting to get CPU-leashed. The typewriter was eviscerated in the process, reduced to a pile of keys, peripheralized to a Machine in which both writer and writing become but one among many: “email,” “Web-surfing,” “game[s]”…. NEO, by association with the typewriter, severs the umbilical plug to distinguish the art and tool of writing once again autonomously from those of computing and (ironically) bureaucracy, and “the Writer” from the common man….

“Man”: because this stand-alone keyboard is for lone rangers, not copyists. Only boys will be (cow)boys on the Frontier delineating the white virgin page from the Wild Wild Web. The typewriter began as a symbol of female autonomy, but ends as a symbol of male autonomy/fertility as defined against the writing assembly lines that absorbed the career woman in the same way webbing and computing now absorb all writers. For the modern-day Romantic, you are only as autonomous as your keyboard. Only NEO can unplug from the Matrix; only NEO can reconnect you with Self and Nature—even if it requires an Internet metaphor (i.e., connection) to do so: NEO “instantly connects you with your thoughts.”

In fact, NEO can do all of the above even better than the real thing (true to nostalgia, it’s a hypertypewriter; “it acts like a hardcore typewriter“)—because it’s light and portable: NEO only has the psychological (whimsical) heft of a typewriter. True, part of the typewriter’s appeal is its machine-ness, but luckily NEO lets you toggle between two modes of technophobic nostalgia: 1) autonomy from modern-day technology; 2) autonomy from the Machine altogether. For, heavy machine-ness also is what chained the typewriter and writer to the bureau in the same way that the subordination of the writing tool to the computing tool chains the keyboard and writer to the computer & the Machine. Moreover, the NEO is quiet—one can bring it into the woods without adulterating Nature’s musicscape—and the battery life is so long as to make the organ seem to have a life of its own, autonomous from the Power grid, powered as though by a hidden Source (if not, environmentally friendlily, by kinetic energy from the writer’s own digits). This means the object becomes material only every 700 hours!—more than enough to write Walden. And less work, too: it’s easier to punch the buttons, and hence easier to unsee writing as labour.

This, all in the name of guarding the fragile independent creative mind from “distractions.” There is an implication, however, that the most important defensive function might be, to protect the writer from (the distractions of) the writing tool itself. The one respect in which NEO resembles neither computer nor typewriter nor Atari nor quill is that there is no screen/page proper. There is a miniscule, slight-angled screen at the top; but looking at text on this is like looking at text not on a page but through a voyeuristic mail slot, and unless you don’t mind hunching over and/or you have no keyboard memorization or typing prowess whatever, then I daresay you’ll be (your head will be) more inclined not to look at the screen/page at all and simply TYPE. Type, and look at…what?

Picture a pen of ink super-volatile once penned. Actually, such a pen is within easy grasp: the tongue, whose “writing” within an oral culture would seem page/screen-less. Or is the “screen” simply the audience? Which is to say, that the paginal equivalent of an oral audience are the scratches/impressions, visibly reacting, within the mirror page, to our performance. The page is like a performance chart or to-do list: put a check mark on each coordinate of the time-table on which you achieved your daily goal; this compels you to want to see more checks. The typewriter’s bell? That’s Pavlovian. What Flusser points to, the necessary “motive” to write and the unseen text from which the writer “copies” (pp. 2, 5-6), are thus perhaps no better represented than by the blank page itself. Moralist police of good writing Strunk & White elaborate:

When writing with a computer [“typewriter” in older editions] you must guard against wordiness. The click and flow of a word processor can be seductive, and you may find yourself adding a few unnecessary words or even a whole passage just to experience the pleasure of running your fingers over the keybaord and watching your words appear on the screen. It is always a good idea to reread your writing later and ruthlessly delete the excess. (p.74)

Enter NEO, a guard against material excesses. “Focus,” orders the Page: “Turn off your targeting computer,” to the space cowboy.

But perhaps NEO’s shown us something: The Page. To look away from the teleprompter (which NEO’s own miniscreen resembles), to a diff-errant audience.

Postscript

NEO can be loosely emulated through your own laptop by running Freedom “Internet Blocking Productivity Software” while having your screen’s brightness turned to zero. (Cf. Darkroom.) A more daring experiment is to simply turn the laptop off.

Intertexts

Flusser, Vilem. “The gesture of writing.”

McLuhan, Marshall. “Front Page.”

NEO. [Ad]. Writer’s Digest. February 2009. p.7.

Strunk, William and E.B. White. The Elements of Style. 7th Ed. p.74.

Note: This article refers to NEO. A “NEO 2” has since been released.

— Kevin Kvas

The post PSYCHODIGITAL HYPERTYPEWRITER appeared first on &.

]]>