The post Electronics & Artistic Production: Interview with the lab coordinator of Eastern Bloc appeared first on &.

]]>Eastern Bloc is an artist-run centre and media lab in Montreal. Since 2007, it has been exploring and pushing the boundaries of the intersections between art, science, and technology. By facilitating hands-on workshops, the centre sets itself apart from commercial galleries insofar as it not only exhibits digital and new media artworks, but helps to educate and provide resources for their production.

The lab’s mandate states that it “provides a platform for experimentation, education and critical thought in practices informed by hybrid, interactive, networked and process-driven approaches.” This includes a mandate to offer a shared lab space involving tools and resources for electronic and digital/new media art. Operating such a lab includes offering technical support, engaging with the community, and reaching out to people who are interested in the artistic use of technology, but may be without the means of producing it. Ideally, this is all in the service of the democratization of technology in a time when we are increasingly alienated from it, despite its prevalence.

I spoke to the Lab Coordinator, Martin Rodriguez, in order to get a better sense of what happens here.

What, if anything, would you say you produce? Is there something material that comes out of this lab, or is it something more intangible, like “knowledge”?

There’s a lot of music synthesizers that are being produced here. That’s one of the main things. There’s a lot of audio works that are happening in our lab right now. We can do everything from fabricating the PCB board, which is like the electronics aspect of it, like just the circuit so you can do multiples. We can make all the casings for them, so there’s the CNC machine which would allow you to cut the wood. Hopefully we will be able to cut aluminum with that.

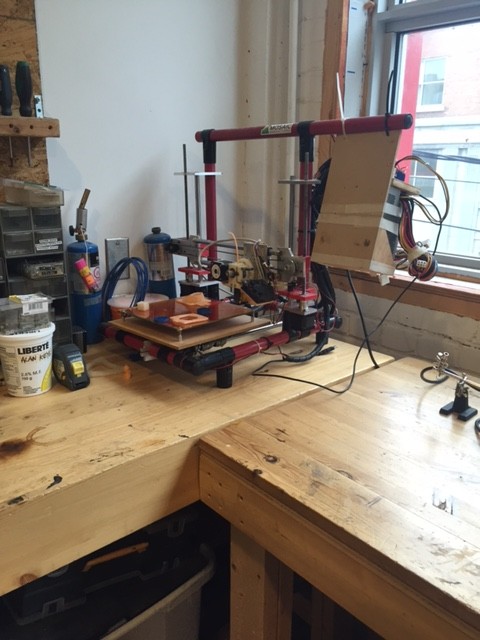

We also have various different types of woodshop tools. We have a 3D printer there, which we just got up and running. That will allow artists to design 3D objects that are more complicated, something that you couldn’t do with a regular wood and milling machine.

Our lab is really geared toward the creation of electronics projects. What I mean by that is we don’t really have a lot of computers in here, it’s not really made for people to be programming software. So we have all the materials you would need for soldering, and different types of wires. Stranded wire and solid wire, different components, different resistors and capacitors.

Do you think a large part of what you do is educating people on how to use these materials? Or is it more of a resource for artists who already have the knowledge to have access to equipment?

The way our lab functions is a little bit of both. We have lab members who pay a fee to have access to the lab 24 hours a day. They often bring a lot of their own equipment because this is just standard stuff. We also offer workshops, which is a way of generating income for ourselves. But it’s also a way for us to talk to the community. I think a lot of the workshops here are getting people to feel comfortable, and understanding what media and electronic art is. So a lot of our workshops will be like intro to arduinos, or introductions to MaxMSP, Pure Data, or Python. And we also have other workshops which are more like, how to do VHS glitch art. We’ve had workshops that are more panel-based, discussions around artists and their processes.

How do you choose who does the workshops? Do you have artists come in or is it the staff that hosts them?

Because the lab is attached to Eastern Bloc, which is an artist-run centre, we have a mandate to support emerging artists so we offer workshops that are given or facilitated by emerging artists. Oftentimes we find that is more engaging or interesting. Because Youtube is such a powerful thing right now, people can find videos and find out how to build a lot of stuff there, but what’s interesting is coming here and being with an artist and finding out what their whole process is.

What is the relationship of the gallery to the lab? Are their projects similarly aligned? Do you integrate the workshop element into the exhibitions?

Yeah, that’s one thing I’ve been trying to pull in recently with the lab. When we have an artist who comes and presents something to also present a workshop. In the summer, an artist called MSHR came and presented here, and after their presentation we tied in a DIY synth workshop. We had these biopolitics exhibits that happened during Fall with workshops tied in. We also have an artist residency program, where an artist will have full access to the laboratory for 2-3 months, and at the end of that they’ll present what they’ve built during that period.

What are your feelings on the space itself? What is its story, and how does it shape the lab?

We’re currently in the process of acquiring more space for the lab. It’s quite small as you can see, it’s under 500 sq feet. So we wanted to switch it over to where the offices are. Right now there are only two of us working, but with interns we can get up to about 5-7 people in the office. The lab needs to be bigger, there are more demands and we need more tools.

A bigger space would allow us to have more machines. If you go to some of the FabLabs, like FabLab du PEC, which is in Hochelega, they have a much bigger space and a lot of interesting tools. Two different types of 3D printers, a laser cutter, a vinyl cutter, a CNC machine. It’s just a massive space. But it’s different, they don’t have a lot these electronics things. We are kind of limited by the space that we have, it’s not easy to create large pieces because there is not a lot of elbow room.

What are the open lab nights like?

Yeah, we’ve been doing the open lab nights, they’ve been running. But as of recently we’ve switched the programming because it was so open that no one came. It was just like, “hey it’s an open lab night come and check it out.” People would just not show up. So I was like, this isn’t working, we need to find a different model. So what I started doing was trying to create themes so we could target specific people. Right now the open lab night we’re having is a sound lab night. I’m hoping we can do something like a programming one, or now that the 3D printer is running we can do a 3D printing lab night.

Is the idea for open lab nights that you can bring people in who aren’t familiar?

Yeah, to bring people in who aren’t familiar, but also to grow a community. With the sound lab night there are a lot of people in Montreal that are fabricating sound, or experimenting with instruments. So we’re trying to create a community around that. And an exchange of ideas, of circuits, of concepts.

Why ‘lab’? What about this space makes it a laboratory, or just, what comes to mind when you hear this word?

Outside of this context when I hear ‘laboratory’ I think of beakers. But I think the larger concept behind it is like, experimentation, and developing something to be accurate and fully functioning. I think that is a lot of what happens here. Maybe the word ‘lab’ has been used so much it’s getting played out, and that’s why people have a bad feeling against the word, its overuse—

Oh, not a bad feeling. But it has certain connotations. Experimentation, a collaborative space where people have to work on ideas together. It’s different than a factory or something where you know exactly what is being produced. It’s kind of indeterminate in that way. I think that’s why people feel compelled to call their space a lab.

Yeah definitely, I think so. I think sometimes the startup scene tries to take those types of words, those buzzwords and make it something. I feel like what we have in spaces like these feels more like a lab, like what we know as a science lab, because of the machines and what is produced and experimented with.

The post Electronics & Artistic Production: Interview with the lab coordinator of Eastern Bloc appeared first on &.

]]>The post SpiderWebShow.ca As Messy Media Lab – Interviews with the team appeared first on &.

]]>I am working with a project called SpiderWebShow.ca as Associate Dramaturg. This volume of the project (which runs from October 2015 to February 2016), we have been working hard to define what we have created and what we are as a service, as an organization, as a constantly evolving organism. Mess and Methods with Dr. Darren Wershler provided the perfect opportunity to push that conversation even further by asking us to define ourselves in terms of space and knowledge production. I asked six of my colleagues to respond to a series of questions: Sarah Stanley (Co-Creator & Artistic Director), Michael Wheeler (Co-Creator & Editor-in-Chief), Adrienne Wong (Artistic Associate & Head Researcher), Laurel Green (Artistic Associate), Camila Diaz-Varela (Digital Production Manager), and Clayton Baraniuk (Associate Producer). We live across the country and all work for various theatre organizations. We all come from different backgrounds. We meet weekly via Google Hangouts. The introduction of these questions into the digital arena of our meetings (and email inboxes) has caused confusion, stress, excitement, anxiety, and illumination. This is an ongoing process and an ongoing conversation. The following are responses from three of my colleagues. As more come in I will be adding additional content. These questions have struck a cord and will be sticking with us well beyond the end of term and this class. For more information about our team and our work, please visit SpiderWebShow.ca.

1. What is the SpiderWebShow space?

Clayton: The Spiderwebshow space is a virtual playground for people trying to sort out how a virtual playground is different than a real playground. It is a place for artists to take risks, experiment, try on new technologies and express themselves in new ways with new mediums. It is a meeting place online for people interested in Canadian theatre in almost any aspect – but particularly for those who make theatre to be inspired or gain insight. The spiderwebshow is also a space in the brains of each of the makers, who define what the spiderwebshow is within their own space.

Camila: I would describe the site to be a portal into contemporary Canadian theatre. Especially into the minds of contemporary Canadian theatre makers right now.

Laurel: SpiderWebShow is a website that acts as a moving, living compendium of projects from artists across Canada. It is a web that reaches out and catches collaborators intrigued by the possibilities of digital space. SpiderWebShow explores what it means to make performance work right now, today, in our country. This space is limitless.

2. What are the daily, or weekly, practices in this space?

Clayton: The biggest practice is the sharing of work, ideas and perspectives. This goes on daily through the social media commentary, sharing of information. Weekly through the projects and articles.

Camila: A daily practice, for me, is clicking around the site to find which nugget of gold I can feature in the day’s social media post. It’s also responding to any comments or communication or engagement with the SWS audience on our social media profiles. Weekly, the makers meet to take steps forward with the work, and I make clear notes on the action points to completed for the next week. We’re always seeming to make baby steps forward, which is awesome.

Laurel: SWS features projects that are updated idiosyncratically by their creators – some are daily, weekly, monthly installments, depending on the vision. SWS includes a bi-weekly magazine called #CdnCult, an opportunity for discourse with contributions from theatre artists across Canada and edited by the SWS team. SWS is also active on social media: Instagram, twitter, facebook – not only using its own channels to promote conversation, but engaging the nation with hastags #cdnopening and #cdncult so that the activities of others can be included in the SWS feed. Once a week, the SWS team – curators and editors, makers all – get together for an online meeting.

3. Describe your involvement with this space? What is your role?

Clayton: I act as a semi-supervisor, watching the content roll out, noting the makers, monitoring the budget and contributing to the ideas, development of new aspects and angles on the site, and lately, providing content to fill the practices of the space.

Camila: I think my role is to be a bit of a third party. I’m actively engaged in showcasing the work of the Makers and showing it to our audience through social media, not necessarily creating my own. There’s so so many cool projects living and growing on the site, so I pluck something from the site and present it on a public platform in a way that’s faster and a bit easier to grasp than looking through the site. I also consciously create structure in a space where all the team members are on different schedules, in different geographical locations, with different priorities. These elements are vital to feeding the work that SpiderWebShow does, but negotiating them requires some agreed upon routine and structure, so my role is to make that by hosting and scheduling meetings, creating action points, and holding Makers accountable.

Laurel: My role as Artistic Associate is to support the vision of our Artistic Director through the curation and dissemination of SWS projects. My primary interest is SWS sound and gallery projects. I liaise with artists, shepherd projects, source new artists of interest, and I contribute as a creator of a sound project myself. I’m also the “Western Correspondent” for SWS, as a member of Calgary’s theatre community.

4. How is knowledge produced in this space? What form does that knowledge take?

Clayton: Knowledge is produced through weekly sharing of ideas, monitoring of growth, depth and span of the work. The knowledge takes form in the entries of the Theatre Wiki, in the projects that take place, though the development and sharing of cdncult. It is also produced through the seeding of ideas within the brains of those passively contributing by watching listening and reading the content, which may inspire them to contribute their knowledge.

Camila: Knowledge is produced because SWS provides opportunities and platforms for theatre artists to engage in questions they wouldn’t normally be asked. There are a wide variety of projects on the site that ask questions like “what do our community elders think?”, “what if theatre artists played with recorded sound?”, and “what are you thinking?” (in the case of Thought Residency), and ask artists to respond to the questions with a medium that is usually not familiar to them. Theatre artists are usually not invited to play with tech + digital mediums so SWS provides a safe place to experiment, because even the Makers are experimenting. It’s a collective push to explore something new.

Laurel: SWS offers readers/viewers/audience a self-directed experience of the knowledge we offer, which takes multiple forms. You can visit the website and engage with sounds, images, and texts at your leisure. In creating a layout for the page overall, we attempted to design an accessible and open space where material was able to speak for itself, often without editorial comment. Our framing devise remains the ‘spiderweb’, every shifting, changing, and growing. I think that this dismantles traditional expectations of expertise, and opens our material up to interpretation. We find that many of our articles or pieces are accessed individually and on their own according to the interests of the viewer. Material can become more or less topical or popular depending on the current conversation.

5. How would (or would it) be different if SpiderWebShow had another space?

Clayton: If the space was not in a virtual world, it would not be at all the same. If the spiderwebshow was in a different virtual world, it is feasible that greater limitations may apply restrictions or censorship. If the spiderwebshow was not so diverse in the space of the many maker-brains, it would not have the reach, breadth of perspective or attitude that it does have.

Camila: By ‘space’ I’m thinking the online, digital space where it lives. If it were not digital and online, it would be in person I suppose. And we wouldn’t be able to get input for artists across the country in real time – the collaborators would just be those who are lucky enough to live close to the initial founding Makers. And the product would have been presented in one community only. And certainly not archived, so it would have disappeared rather quickly, as opposed to now when I can search through the archive to find still-relevant work to feature on social media.

Laurel: If SWS attempted to occupy a physical space it would be part newsroom, part rehearsal hall, part café, part theatre venue, part darkroom, part recording studio, part lounge. The kind of place that we’d all want to visit. Having to pick the city where we would build amazing building would be too challenging and inevitably lead to the exclusion of most of the country’s practitioners. Because we occupy web space, we can be a point of connection for everyone who is in the digital neighbourhood.

6. How do institutional relationships affect this space and the ways in which knowledge can be produced?

Clayton: Institutional relationships can foster great focus and depth in the scope of content and lend specificity. From my own perspective, the NAC Institutional relationship brings a focus of national knowledge building and collective national creationism. These can also hinder and impose limitations or narrow fields for exploration by giving too great an emphasis to one avenue – like the Theatrewiki becoming the performancewiki.

Camila: I’m really intrigued with how SWS works with universities and colleges. One reason I can see for this is because students are exclusively focused on building their skills, gaining knowledge, and considering the future (theirs and their industry’s) and can be a great motivator and instigator for new thought in the digital + art realm. If the Makers share what they’re learning about this new fusion of theatre + tech, students can learn from it and run with it after they graduate. Institutions also provide structure and financial support to this project, which is very amorphous and grows with every Volume. For me personally, I’m being financially supported by Theatre Ontario to work with SpiderWebShow for this Volume. This relationship provides me with financial support, and provides SWS with administrative support. It allows for an emerging artist who would normally not be able to dive into a mentorship so completely (because financial strain and lack of guidance) to engage with more experienced artists who are willing to share their knowledge. So the institutional connections that I see SWS having connect them with a younger generation of thinkers from both artistic and technical backgrounds, as well as financial support.

Laurel: Each member of the team brings their institutional relationships to their work with SWS, and this has mostly offered some fabulous opportunities like additional funding and a place to hold group meeting IRL. Being aligned with these institutions also lends cache to our project as it continues to evolve, while SWS lends indie cred back to the institution. It has been rare that we have encountered limitations or any conflicts of interests, however I will say that the regional balance on our team and the institutions they work with do lean very Eastern in our country. There have been moments where, because of the institution I work with being located in the West, I approached a topic with what felt like a very different, and sometimes irreconcilable, perspective to the rest of the team.

The post SpiderWebShow.ca As Messy Media Lab – Interviews with the team appeared first on &.

]]>The post The music and multimedia research-creation laboratory at Université Laval appeared first on &.

]]>On December 4th, 2015 I interviewed Sophie Stévance (Professor and Canada Research Chair in Research-Creation in Music) and Serge Lacasse (Professor in musicology) about their work with the CFI and OIF funded LARCEM (Laboratory for research-creation in music and multimedia) based at University Laval in Quebec City.

I was interested in finding out more about their process as researchers working collaboratively in a creative laboratory space. Having read some of their recent publications including Research-Creation in Music as a Collaborative Space and Les Enjeux de la recherche-creation en musique I was curious how they viewed the importance of the space in which they conducted their research.

The following is a summary of our Skype conversation. I have not transcribed my recording word for word in the interest of being concise. I sent some questions in advance and we began our conversation here.

I asked: How does the LARC studio space affect your research-creation projects? What are the specific aspects of the space that influence what goes on inside and what is produced there? Was the space designed collaboratively to enable research-creation projects?

The LARC was designed to be a recording studio of the highest quality that would be suitable for collaborative research-creation projects. It features a large central space for musicians, a main control room, as well as 3 smaller control rooms which can all be linked. This allows people to work individually or together on various projects. The space has excellent acoustics which has a huge impact on the musicians’ experience and the quality of their work. Lacasse described one violist who exclaimed after playing in LARC that “It’s the first time I feel like I’m playing music!” Not surprisingly the researchers who are now using the space were heavily involved in the design process. Stévance and Lacasse describe a smooth process working with acoustic architect and designer Martin Pilchner, although they had to explain many of the specific requirements of their space to the university’s facility services (service des immeubles) since it was an unconventional building project. There’s no doubt that having a state of the art facility affects the quality of the work accomplished but it also enables the researchers to invite high profile performers to collaborate and use the space. In discussing collaborative projects our conversation shifted toward what happens within the “microcosm” of the recording studio.

The LARC is mainly a recording studio but it is also a research space. Stévance and Lacasse emphasize that each project is unique and driven by those involved in the collaboration. Musicians don’t magically become researchers because they’ve entered into a space where research is also happening. Research-creation happens when there is a reciprocal and symbiotic relationship between the collaborators. The infrastructure they’ve established allows them to work directly with musicians and researchers to create in real time while simultaneously studying the process that unfolds. The skills, abilities and talents of each collaborator informs what happens in the studio. Lacasse works as a musicologist, a researcher, and a musician but not at the same time. The process is very spontaneous but is closely examined as well.

Stévance and Lacasse offered an example of a collaboration undertaken with Inuit artist Tanya Tagaq. Stévance had been studying the work of Tagaq since 2007 and invited her to record some of her 2013 album Animism at LARC. Stévance was able to study Tagaq’s creative process in person, as it developed in the studio. Lacasse was also participating in the project, he got involved with the sound mixing and later contributed some percussion work to the recording session. When Tagaq observed Stévance’s notations (which mapped Tagaq’s improvisational process) the singer became interested in the musicological research and this analysis in turn informed her vocal performance. Stévance and Lacasse offer a more detailed account of this work with Tagaq in their publications, but this example demonstrates how participants change roles and how what emerges from a collaboration cannot be anticipated beforehand. Tagaq will return to the LARC to work on her 4th studio album in January 2016 and she will also be performing at the Palais Montcalm on February 18th. This live show will further inform Stévance’s research into Tagaq’s performative choices including how her bodily movements relate to her vocals in a live concert setting.

Given the spontaneous, emergent, participant-driven nature of their research-creation work, I asked my interviewees if they had specific strategies for acquiring funding. They expressed that this was an area of concern particularly because of the unique nature of research-creation as being not just research or creation. Research-creation committees at SSHRC and especially FRQSC, for example, have adjudicators that are accustomed to evaluating the artistic merit of a project, and they may not value the research contributions at all. Lacasse gave me an example of applying for an FRQSC grant and being told to remove the research portion of his application, which he did in order to get the research-creation grant.

This interview helped me think through the similarities between a media lab and the recording studio. Both are heterotopic spaces that have a mysterious quality in terms of what goes on inside. Laborious creative processes occur, often collaboratively, and research reflecting on these processes is produced. Media labs are heterogeneous spaces that can shift and evolve over time. Cutting-edge technologies inform the work being done and funding increases the chances of having tools that improve the quality of what the lab produces, as well as the calibre of researchers and guests invited to work within the space. Branding a workspace as a media lab creates an identity with the potential to bring people together to birth ideas, build prototypes, access funding, and produce research (often collaboratively). Sophie Stévance and Serge Lacasse have clearly defined their process as research-creation and they use this term effectively to describe to their unique research practice and the spaces in which their collaborations transpire.

The post The music and multimedia research-creation laboratory at Université Laval appeared first on &.

]]>The post The Media Lab as Space for “Play and Process”: An Interview with TML’s Navid Navab appeared first on &.

]]>The point is to build environments that are “not complicated but rich.” At the TML, we live with our designs, within our responsive environment.

Interview with Navid Navab

Associate Director in Responsive Media, Topological Media Lab

Research-Associate, Matralab

Multidisciplinary Composer

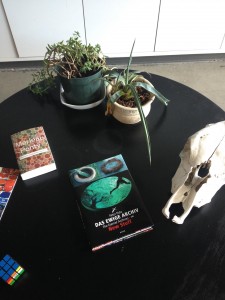

The Topological Media Lab (TML) is a large, open space with polished concrete floors and a long wall of windows punctuated by various hanging plants and black-out curtains. The room is canopied by a maze of light bulbs, microphones and wires that dangle from the tall ceiling, all of which goes unnoticed if your eyes are preoccupied with the other strange and wonderful objects that inhabit the lab – on one low coffee table, a deer skull sits nonchalantly next to a Rubik’s cube and Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception.

The first time I attempt to locate the TML, I find myself wandering through the shiny halls on EV 7, pondering the chaotic numbering systems of the future. Lucky for me, Navid Navab – multidisciplinary artist, “media alchemist,” thinker/maker – embraces chaos (and knows these halls well). Navab, who is also Associate Director in Responsive Media at the TML, kindly fetches and leads me to room 7.725, the space where he works, researches and creates. We speak at length about the design and philosophy of the lab, as well as the various projects that have been explored there, and are eventually joined by Michael Montanaro, co-director of TML and chair of Contemporary Dance at Concordia. The conversation is both delightful and at times mystifying. I begin to jot down terms like “gesture bending” and “subjectivation,” planning to Google them later…

The dance/new media projects that have emerged out of TML are what first piqued my interest in the lab. The “Shadows and Light” sequence in TML’s Einstein’s Dreams (2013) presents a space in which performers interact with media as they move through the space, “dragging” pools of light with their bodies as they dance. Another example is performer/creator Teoma Naccarato, whose past research with TML has contributed to her practice, which integrates contemporary dance with interactive video, as well as audio and biosensor technologies to navigate material and virtual scenarios.

Several weeks after speaking with Navid and Michael, I decided to ask a few more questions, via email. Navid’s writing style is almost identical to his mode of speaking; he meanders deftly and with charm between topics as diverse as teamwork, dance improvisation, operating theatres for surgeons, grant-writing and Felix Guattari. Because of this, I’ve provided a glossary of terms at the end of the interview to help readers navigate.

Here’s what Navid had to say:

HB: What is the Topological Media Lab?

NN: The TML (Topological Media Lab) was established in 2001 as a trans-disciplinary atelier-laboratory for collaborative research-creation. In 2005, TML moved to Concordia University’s Hexagram research network. Following the departure of the founding director Sha Xin Wei in 2013, the TML was restructured to sustain as an autonomous laboratory for the critical study of media art and sciences at Concordia University.

As articulated on our website, TML’s projects serve as case studies in the construction of fresh modes of knowledge, bringing together practices of speculative inquiry, scientific investigation and artistic research-creation. Currently, TML’s technical research areas include: responsive environments, active media, computational-materials, and gesture bending. Its application areas lie in movement arts, speculative architecture, and experimental philosophy.

The TML is both an atelier and a laboratory for research in improvisatory gesture from both humane and non-anthropocentric perspectives. Our atelier research investigates the process of subjectivation, agency and materiality from phenomenological, social and computational perspectives. It approaches this by suspending assumptions about what we think are egos, humans, machines, objects, and subjects. Instead, we consider the transformations of things, and see how these things emerge through play and process. This method is informed by a continuous (rather than tokenized object/grammar-based) approach to material change, hence the “topological” aspect. Topology is concerned with the non-metric (non-numerical) properties of space and the continuous, dynamic relationships through which space is constituted.

HB: How did you originally become affiliated with TML?

NN: I first become affiliated with the TML in 2008 as a curious student — occasionally dropping in, apprenticing with inspiring thinker-makers — and shortly after as a core artist-researcher and co-author of projects. I was given sufficient autonomy to freely innovate my own voice and in a few years I was initiating and leading multiple research streams of my own. Each research stream would investigate a particular question or phenomenon that interested me, which I would explore through organized discussions, intensive material-computational research-creation, and eventually through live experiments, workshops, engineered software environments, published works of art, and peer reviewed publications. The studio-lab supported these diverse activities both intellectually and logistically, thus enabling my pursuit of passionate and radically fresh art-research without having to constantly defend these investigations in institutional language (e.g. of disciplines, granting agencies) or in terms of the market.

Over the years my activities have enriched and shaped the environment of TML, leading to my role as Director in Responsive Media, in collaboration with the lab’s current co-director Michael Montanaro.

HB: How many other people are involved regularly at TML?

NN: TML welcomes curious passersby to drop in and engage with its ecology of practice. TML’s long-term research-experiments are driven by a small group of 6 or 7 actively present members: directors, administrators, core artist-researchers, and research-assistants. We are also in constant exchange and collaboration with our international partners at top institutions and centres around the world. Additionally, TML hosts a continually shifting and returning array of newbies, apprentices, students, artists in residence, visiting scholars, international partners, artists and hackers.

HB: What are the practices that happen at TML on a daily basis? How does knowledge emerge out of the TML and what is the material form of that knowledge?

NN: Practical domains for art research at TML are:

theory: imagine, make, explore, articulate and evaluate concepts rigorously

art: ethical-aesthetic gesture and creative ways of being with others

technique: (for) collective innovation, improvisation, and play

The TML stores group knowledge, an apparatus structured by ongoing experiments, from which members take what they need in order to make experiments, and to which they contribute pieces that others can use in the future. The apparatus is made up of various components such as physical things, material samples, software, documentation, videos, reports and procedures.

The TML is not a production facility for individual art projects.

It is a place for building sketches and experiments with larger ambition for impact, and which requires the collective talent, expertise, and energy of a small team. The TML is a nexus for art-research (neither art production nor technology development) with a family of themes with philosophical or critical value such as:

– ethico-aesthetic play

– distributed agency

– materiality

– gesture and movement

– phenomenology of performance

– critical studies of media arts and sciences

These themes are elastic and have evolved over the years around the joint interests of an affiliate community of artists, researchers and philosophers who engage with the lab. These themes also take material form, as works of art, performances, engineered instruments or systems, essays, peer-reviewed papers and documentary videos.

Besides making stuff and overseeing research experiments, we also situate TML’s activity within the contemporaneous global context, and locate funding for our affiliate researchers so that individual members can pursue their work with more autonomy and freedom. In exchange, we expect work of world class quality (not student class project work) which should aspire not merely to tech art venues (such as Ars Electronica), but also to real world, socially embedded situations.

HB: How does the material space of TML affect the products and processes that occur within the lab?

NN: Some of TML’s experiments use active lighting and acoustic conditioning systems to change the apparent physical qualities of interior or exterior space. The point of this work is to build environments that are, to quote Xin Wei Sha, “not complicated but rich.” The TML space was designed from the ground up by the founding members, Sha Xin Wei and Harry Smoke, to handle demanding and diverse sets of events and technological structures. The configuration of the space is itself continually shaped under ongoing research. At the TML, we live with our designs, within our responsive environment. Our research-creations are thus always put into unscripted play and place. This approach results in responsive designs that at once address everyday functions, inform ambient aesthetics and enable virtuosic improvisations, all within one holistic, responsive environment — the TML itself.

Our designs and concepts are not invented in a “black box” and they are not made with black-boxed technologies; they are co-articulated through TML’s ongoing dynamic and spatial apparatus that is never turned “off”: a responsive environment full of rich contingent activity.

Therefore, the space at TML is itself a live apparatus for enacting knowledge in a collective fashion. Projects conducted in the atelier draw on and also contribute to ongoing research in the computational and natural sciences, seeking to understand the dynamic interplays of social, psychical and material space.

(Consider Navab’s delightful description of the “ecology” of the Topological Media Lab in the imagined scenario below)

…a visiting person’s shy manner of walking into TML gently perturbs our responsive ecology—very much the same way a lost traveler’s careful steps in an autumnal forest perturb the surrounding life, resulting in fields of distributed activity. A few researchers and artists are busy making stuff and a group of people at the far corner of the lab are participating in a seminar. Through the responsive environment, the inhabitants of TML are gently made aware of a different-presence in the lab and yet this awareness—this ambient behavioural resonance—does not cost their full foci of attention. One research assistant walks to the new comer to welcome them into the space….

HB: What is the difference between the Topological Media Lab and the other space where you are affiliated, the MatraLab?

NN: TML and Matralab occasionally collaborate on projects, share talent and often support each other in large-scale initiatives. Despite their partnerships and similarities, the two labs are however completely independent of one another, each with their very particular and unique vision, process and agenda. Matralab is a research space of inter-x art directed by Sandeep Bhagwati, “dedicated to using interdisciplinary art practice to bridge the gap between emerging art forms and their aesthetic reflection.” Matralab’s core activities revolve around experimental musical events, and comprovisational environments to name a few. Matralab’s research is leading to the establishment of a practical and theoretical framework for the creation and evaluation of interdisciplinary, intercultural, intermedial and interactive art.

HB: How important is dance/movement to the work done at TML? I know you work with dancers regularly – can you talk briefly about what it’s like to collaborate with dancers?

NN: One of TML’s strategic goals is to transpose insights from movement and performance into the design of durable, everyday situations, and experimental environments. We leverage our pre-verbal intuition of physical materials and embodied knowledge to explore the ways in which bodily relations are felt and understood. For example, we do experiments that explore when movements can be regarded as volitional rather than accidental, and when movements—perhaps among multiple bodies and things—can be regarded as a single gesture. The emphasis is often on continuous, unanticipated movement that may be improvised freely by those within the conditioned space.

Our ongoing GestureBending* experiments explore how everyday gestures can become charged with symbolic intensity and used for improvised-play.

Close collaborations with dancers and performers are extremely unique and precious opportunities for rigorous co-creation, refinement, and embodied evaluation of gestural media and responsive environments.

What is evaluated is the media/matter/environment’s potential for play—in its ability for allowing boundlessly open sets of a priori gestures and experiences by the participants to acquire expressive, playful and poetic force. If successful, participants’ gestures not only lead to unexpected meaning and instrumentality but to narratives about and recognizing daily life and the material world as a platform for play and for refined practice. Such a design approach allows for any potential movement at all by the participants to turn into a potentially co-expressive art-event. This removes the burden of modeling the human experience through mimetic performativity and instead allows for such notions as gestural meaning, intentionality, expressivity, noise, musicality, and even performer, performed and spectator to freely arise from the context established in the moment of performance.

So in a sense—to maximize improvised co-expressivity and synergetic play— it is helpful for performers to unlearn presumptions about what it means to interact with responsive media and instead maneuver embodied intuition, to improvise gestures as they already always have in continuous media like fabric, flesh, water, air, and mud. When designing performative media (an installation, instrument, or a responsive scenography), even when rigorously staging theatrical events with virtuosic performers, who are welcome to incorporate or invent their own very unique sets of gestural vocabularies, we maintain the position to never model or presume, at least in our design metaphors, what constitutes a gesture or a body. We condition performative events that potentialize improvised play, always working with a priori non-anthropocentric movement and contingent activity. Therefore solo dancers, groups of passersby, and even non-humans objects and subjects are all treated (computationally and conceptually) as fields of stuff and process. Within this continuously responsive field—fusing humans, non-humans, media, matter, and energy— solo dancers as well as other (non)human performers can improvise nuanced gestural expressions, co-constituting and enacting one another in the ever-changing field that forms them!

At TML’s recent GestureBending workshops, resulting from my ongoing collaboration with expert dancers, participants discovered that their everyday movement can create intricate sonic textures and developed their own unique vocabulary of sound generation to sculpt musical events via intuitive movement and embodied engagement with computationally enchanted materials. Leveraging the GestureBending apparatus, renowned TML performance works such as Practices of Everyday Life | Cooking symbolically charge everyday actions and objects in ways that combine the composer’s design with the performer’s contingent nuance.

What we are suggesting is a holistic shift from representational technologies to performative media, from nouns to verbs, from objects to fields of matter-in-process, from a priori concepts to processes that enact concepts. To adapt Mcluhan, instead of encoding and decoding a presumed message we are enchanting the medium!

I chose to close my interview with a question about dance because I am fascinated by the potential that interactions with new media hold for dance and the moving body, and I know that TML is also intrigued by these collaborations. When Navid explained GestureBending to me in person, he flung his left arm out into space and asked me to imagine a sound that followed from the movement of his body, unexpected, off in the distance, as if resulting from his thrown arm. A performer improvising amidst a soundscape such as this would be affected by the sounds their own body was “producing,” thus enlivening their own improvisational impulses. With GestureBending, sound (or light, or some other vibrant force) is shaped by the dancer (controlled by their movements) and likewise the dancer’s movements are shaped by the elements that interact/play with their body. The space of the Topological Media Lab, with its hung lights, mics and sensors, and its smooth, clear floor, perfect for movement through space, is an ideal space for this type of improvised “duet,” a fact which underscores the importance of built space to the forms of knowledge that can emerge out of the lab.

Glossary of Terms:

Topology: A mathematics term for the study of open sets in which a given set is a “topological space.” Topology is developed out of geometry and set theory and is interested in the the deformation, stretching, transformation and bending of space and dimensions through a concept of connectedness. For example, “a circle is topologically equivalent to an ellipse (into which it can be deformed by stretching).”

Subjectivation: A philosophical term/concept invented by Michel Foucault and explored further by Deleuze and Guattari which “refers to the construction of the individual subject.” Also corresponds to Althusser’s concept of interpellation and is sometimes called “subjectification.”

Gesture Bending (Navab’s definition): A generic term coined by Navab, which refers to the poetic transformation and enrichment of gestures through instrumental augmentation or technical mediation of movement. The goal is to continuously enact persuasive conditions for the transformation of networks of meaning production in the embodiment of movement. Pervasive Gesture Bending can potentialize improvised-play, leading to emergence of conditions that could invite performers to synergistically improvise with a hybrid expressive force.

Speculative Architecture: This book review may help to define this complex term.

Black Box Systems: A device, system or object which is defined by its inputs and outputs without consideration or knowledge of its inner workings. This term is most often used in science, computing and engineering, and can be applied to many objects, like a transistor, an algorithm or even the human brain.

Comprovisational: Navab’s term for compositional techniques used to explore blends between fixed composition and free improvisation with interactive performance systems.

Ethico-Aesthetic Play: Navab uses this term to adapt Guattari’s concept of the coming into formation of subjectivity (or Subjectivation, above), through an engagement in art, dance, performance and improvisation. In Xin Wei’s words, “to conduct philosophical speculation by articulating matter in poetic motion, whose aesthetic meaning and symbolic power are felt as much as perceived.”

Find out more about the Topological Media Lab on their website.

The post The Media Lab as Space for “Play and Process”: An Interview with TML’s Navid Navab appeared first on &.

]]>The post Navigating Interdisciplinary Digital Media Labs: An Interview with Erica Lehrer, Director of CEREV appeared first on &.

]]>By Sabah Haider

In this interview for the graduate seminar HUMA 888: Mess and Method [Fall 2015, “What is a Media Lab?” edition], Sabah Haider, PhD Student at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Society and Culture at Concordia University interviews Dr. Erica Lehrer, Director of CEREV and Associate Professor, History and Sociology and Anthropology (joint-appointment), and Canada Research Chair in Post-Conflict Memory and Ethnography & Museology, at Concordia University. In this interview, Haider seeks to gain insight from Lehrer on how interdisciplinary research engages with technology and the fast evolving Digital Humanities.

EL: First of all, I should begin by saying that CEREV is in the process of separating itself from our lab space, which itself is being renamed the Centre for Curating and Public Scholarship. I didn’t want my own preoccupations with difficult, contested histories and cultural issues to dominate a lab space that could be accessible to many more users who share my concerns with using exhibition or curatorial work as a form of public scholarship. So in the future CEREV will be one of a number of units and groups of people using the CCPS lab platform. It was also a question of stability. There is no lab work without lab funding supporting lab staff, and the model we had was too narrow to be financially sustainable.

SH: The Centre for Ethnographic Research and Exhibition in the Aftermath of Violence (CEREV) is a media lab that fosters the intersection of many disciplines/disciplinary approaches to produce broader understandings and to challenge existing understandings around ideas of the exhibition of trauma and violence. On the CEREV it states the centre was established “to create a community of researchers and curators and produce new knowledge around issues of culture and identity in the aftermath of violence.” In relation to the practical side of this — how can you describe or explain how knowledge is produced at CEREV?

EL: Different kinds of knowledge are produced at different nodes in the network of sites and people that make up CEREV. We have an incubator room with computers, and more importantly a round table, where postdocs and students (and sometimes me) meet and talk; we have our exhibition lab, where curatorial experiments and public presentations take place; periodically we have large-scale public exhibitions at various local or international sites; we meet in homes or cafes or my office for more casual mentoring chats; and then we have our website and Facebook page. These are all parts of “the lab,” and the spatial aspect is centrally important to what kind of knowledge is produced, and who participates in its production. I would say that knowledge is produced individually in reading, looking, and thinking; it is produced socially in interdisciplinary, multi-level, and inter-subjective dialogue, negotiation, constructive mutual challenging (sometimes uncomfortable), and in shared experience among differently positioned people; it is produced in a process of making, building, and experimenting with various media; and (for those who only come into contact with things we produce) I hope knowledge is produced in inspiration and the generation of new ways of thinking and seeing. For me the key to “lab-ness” is the special process of collaborative creation – we all help each other to think through and envision a product even if it ultimately is put out into the world under a sole author. I’ve always liked (and used) Gina Hiatt’s manifesto, “We Need Humanities Labs.”[1]

SH: How does CEREV engage with digital technologies to stimulate this? Since the lab’s creation in 2010, has there been an increasing interest in also exploring relevant digital forms and practices, in parallel with the growth or expansion of the digital humanities (DH), particularly as the DH has spawned a seemingly infinite number of digital tools that facilitate new types of exploration?

EL: Playing with new technologies can generate ideas, and that’s why we have our indispensible Director of Technology, Lex Milton, who crucially has a background in educational technologies. He’s an excellent muse, who can listen to logo-centric humanities scholars and help them think about how they might expand and “curate” their projects in productive ways by imagining what technology can do. But I’m not so compelled by projects that use technology as a starting point – or perhaps I mean humanists are not best-positioned to start from everything that “can be done” and then try to figure out how to use XYZ bells and whistles in their own work. Rather I think we do best when we have a particular problem we want to solve – like getting multiple voices or perspectives visible/audible around an object, or getting people who are far away from each other into dialogue, or creating options for accessing and exploring massive archives of information in a single space, or moving people emotionally – and then thinking about what might help us do that. This is when dialogues between humanists (or social scientists) and people with technical and creative skills are most productive. We dream aloud, we share our challenges, and they suggest possible solutions using the technologies that exist. And we humanists push the tech people by asking them “do you think you could make it do XYZ?” It’s a really exciting dialogue, and the final products are always something neither party could have envisioned on their own. We stretch each other.

SH: What are some of the emergent media forms that the lab has incorporated/is incorporating? How can you describe the materiality of the CEREV space? (i.e. mobile, virtual, etc.) What kinds of material forms (i.e. forms of output) does the knowledge produced at CEREV take? What types of ethnographic experimentation has/does CEREV facilitated/facilitate?

EL: I alluded to the various materialities linked to the CEREV lab above. We do have a couple of dedicated physical spaces, and the exhibition lab in particular has a lot of technical tools – projectors, mobile screens (some of them touchscreens), iPads, surround sound capability, etc. – as well as analog ones like pedestals and screens and curtains. And then lots of recording equipment for still image, video, and sound. We facilitate whatever kinds of technology-enhanced fieldwork people want to do, which includes documentation as well as bringing various pre-produced media to field sites, or to co-produce media with various research interlocutors. The forms of output range from ideas to lectures, blog posts, scholarly publications, videos, and exhibitions.

SH: Most of the work of CEREV affiliates appears focused on themes of meaning, affiliation, curation and exhibition. Trauma and suffering, as you have identified, encompasses victims, perpetrators and bystanders or observers. Has/does research at CEREV explored/explore all three of these perspectives/positions — or relationships between them?

EL: I would say yes, we’ve created work looking at these positions and their interrelations. PhD student Florencia Marchetti has been creating field-research-based videos made at a site of a former detention and torture centre in Argentina, which she then uses to seed discussions among the people who today live nearby – some of them were bystanders at the time the centre was operational and they are bystanders to memory today. Students re-curated the video testimony of a Montreal Holocaust survivor to explore victim narratives and their forms and uses. And my own work has dealt with how to raise difficult questions that implicate audiences in their own collective “perpetrator-hood” regarding historical violence and its contemporary legacies or ongoing prejudices. These are just a few projects but they cover all the positions you mention.

SH: What does it mean to have this kind of space as an interdisciplinary scholar — a ethnographer/historian/anthropologist?

EL: It’s mostly challenging. It makes one realize how comfortable text is – both in terms of the limitations of creating it and its relatively limited reception. When you have to deal with capturing and transmitting so many more dimensions of experience, and when such a large public audience can respond (and challenge) what you create, one is confronted with the limitations of one’s own view.

SH: Has anyone outside of your research community (i.e. from the wider “at large” community taken interest in your space, and if so why and how?

EL: Yes, people from various communities, like the Black community in Little Burgundy, or members of the Armenian, Palestinian, and Jewish communities, as well as AIDS activists are just some of the groups that have seen in the lab a space to gather to create and debate representations of history and culture relevant to their own groups. You can read a bit more about the projects we’ve done in the lab, and my own trajectory, at: http://cerev.cohds.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Abell-interview-with-EL.pdf

// END

[1] Hiatt, Gina, “We Need Humanities Labs”, Site URL: <https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2005/10/26/we-need-humanities-labs>

FOR A FULL PDF OF THE INTERVIEW CLICK BELOW

HUMA 888 Interview_CEREV_Erica Lehrer_by Sabah Haider

The post Navigating Interdisciplinary Digital Media Labs: An Interview with Erica Lehrer, Director of CEREV appeared first on &.

]]>The post WELCOME to the Techno-Dystopian Future! appeared first on &.

]]>In this probe I will examine the enchanting and problematic trope of thinking about the future as an abstract, fictional and perpetually deferred time. I will describe the present in relation to techno-utopian ideas of the past and attempt to map out what a humanities-based media lab can enable for researchers concerned about utopian representations of the technological.

Yesterday’s Future

Much speculation about the future of humans and machines is born in the world of science-fiction. Unfortunately this creative genre of literature often relies on certain themes and stock scenarios that easily ignore logistical aspects such as energy (Ghosh, 1992). Since the nineteenth century, celebratory expos and world’s fairs have taken imaginative futuristic concepts and put them on display alongside exotic imported cultural expositions from around the world. Art works were also displayed as samplings from human cultural history to complete the narratives and frame the technologies of the future.

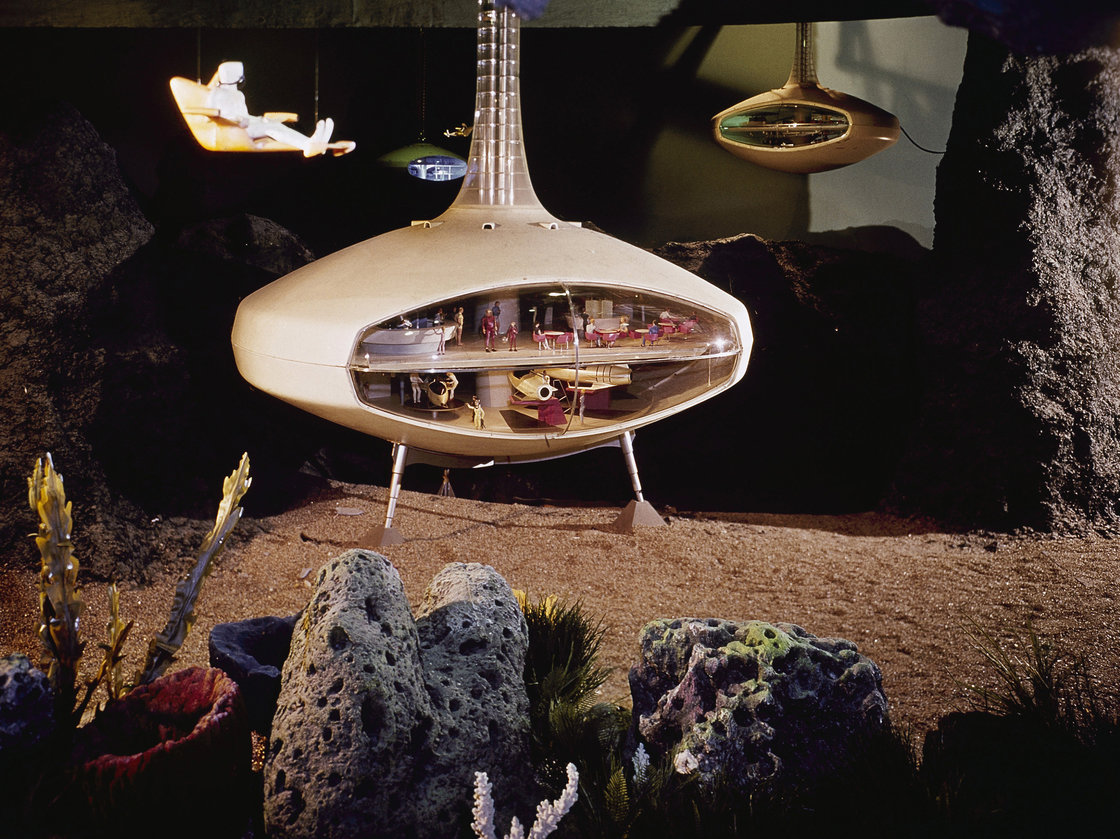

A brief overview of the technologies of the future presented at the 1964 New York World’s Fair include picture phones, hotels under the sea, and giant machines that would cut through jungles to build roads bringing “the goods and materials of progress and prosperity” to newly productive communities. (Futurama II exposition video 4m15s – 5m00s).

According to this archival video promoting the Futurama II exhibit at the 1964 fair, the technology of the future will “free the mind and the spirit as it improves the well-being of mankind”. This video exemplifies the American-centric, man-over-nature, positivist ethos of the day. I found the promotional video simultaneously quaint and irritating but a more politically correct version of techno-utopian thinking is still quite common today. In their 1997 contribution to the book Beyond Calculation: The Next Fifty Years of Computing, technological determinists and Microsoft employees Gordon Bell and James N. Gray offer the following:

“In 2047 almost all information will be in cyberspace – including a large percentage of knowledge and creative works. All information about physical objects, including humans, buildings, processes and organisations, will be online. This trend is both desirable and inevitable.” (Denning, 5)

Isn’t there a more nuanced, critical and reflexive way of thinking about the future? In what ways have academic researchers been involved in shaping technological innovation?

Stewart Brand’s book The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT proclaims in its title exactly what MIT Media Lab founder Nicholas Negroponte wants people to think goes on in the multi-million dollar laboratory. Through extensive discussions with Negroponte Brand paints a picture of the Media Lab that is closer to advertisement than critical examination. As stated on page 263, one goal of the book was to help the lab consider what its emergent academic discipline might be. The author claims to have failed to accomplish this task. I think Brand’s error may have been to ‘drink the kool-aid’ by buying in to the lab’s exciting promise of “inventing the future”. While the book provides a useful exposé of the projects and infrastructure of MIT’s Media Lab at the turn of the twenty-first century, Robert Hassan effectively summarizes the issues inherent in the lab’s ideology in his article The MIT Media Lab: techno dream factory or alienation as a way of life?

“The informational ecology is unproblematic for corporate capital that underwrites the Media Lab. Indeed, big business views it as vital to the future viability of the so-called ‘new economy’. As they see it, interconnectivity and the new economy go hand in hand, a friction-free and networkable cycle of production, distribution and consumption.” (Hassan, 104)

The Media Lab was poised to cater to the newly merged industries of computing, broadcast and motion picture industries, and print publishing. Negroponte was able to consistently secure millions of dollars for the lab from corporate investors who in return get a glimpse of the “future”. Fantastical conceptualisations of the future and the perpetual deference of crisis to a time where problems magically disappear through innovation is part and parcel of the story of capitalism. This mode of thinking is particularly evident and problematic as economies rely increasingly on credit. It is an ethos reminiscent of MIT professor Marvin Minsky’s philosophy of “messy coding” which favours writing extra code to fix bugs (programming problems) before they manifest rather than fixing problematic code at the source (Brand, 102).

The following quotation by David Thornburg which opens Brand’s chapter about MIT’s funding structure is a good example of the paradox of actually inventing the future:

“One of the worst things that Xerox ever did was to describe something as the office of the future, because if something is the office of the future, you never finish it. There’s never any thing to ship, because once it works, it’s the office of today. And who wants to work in the office of today?” (Brand, 155)

This concept is surely not a problem for companies accustomed to the common mode of advertising that promises consumers virtuous, luxurious, fulfilling products and services until they actually make the purchase, at which point the next product will take over this promise.

Today’s future

“Tinbergen found that the herring gull has a default rule: if you’re out of your nest and you don’t see a straw and there isn’t one in your mouth, then just wander around aimlessly. What you do when there’s nothing special to do always involves activity hoping something will turn up.” (Brand, 103)

This quotation from Marvin Minsky in chapter 6 of Brand’s book simultaneously brings to mind a meditative stroll, consumerism, and a resistance to idleness. Brand and Minsky were discussing how to deal with conflicting priorities.

“Work-life balance” is a trendy term used to describe the erosion of the division between labour and leisure due to communication technology bringing work into homes, and pockets through mobile devices. The initial separation of life from work came when technology provided citizens with leisure time. Prior to the industrial revolution life was mostly work.

The influential economist John Maynard Keynes predicted in 1928 that “by 2028 people wouldn’t need to work more than three hours a day”. Elizabeth Kolbert begins her book review No Time with this famous quotation by Keynes and goes on to describe theories from Brigid Schulte’s recent book Overwhelmed: Work, Love, and Play When No One Has the Time. One of Schulte’s theories is that the social status now associated with being busy has caused people to out-schedule one another. A second theory posited by Schulte relates to the personal conception of being busy — by never mentally taking a break, one could feel overwhelmed even while not doing anything.

The tired expression “time is money” explains and justifies the perceived value of work, because of the amount of compensation lost by not working. Viewing time as an economic entity has contributed to the shift that Barbara Adam calls chronoscopic time (Hassan, 90). This compression of time and space through technological tools has tangible effects on our lives. From companies such as Amazon asking employees to work over 80 hours per week to micro jobs that take minutes and pay pennies, the shifting nature of time is one aspect of the futuristic present that bears examination in relation to technology, society and culture.

What can a media lab do?

The humanities, like most academic disciplines, have shifted with scholarly trends leading to new areas of research such as the digital humanities, and the post-humanities. It’s important however not to diminish established disciplinary ground by changing a department too swiftly with emergent research. Similarly, enough interest in cross-disciplinary research could cause departments to merge.

Perhaps what a media lab can do is create a flexible enclave within which to house a research program that could reach across disciplines and explore new topics safely (without de-stabilizing the field it emerged from). The MIT Media Lab is the marital bed of ICT companies and researchers at the leading edge of technological development. Few other places can do what MIT does, nor do they need to. What media labs do at other academic institutions can vary based on the needs of researchers. Labs have a vital role to fulfill in promoting the humanities, social sciences and arts through the production of discourse that enables emergent critical thinking in these fields. The kinds of partnerships that keep funds flowing into MIT’s projects could work elsewhere, and may be worth seeking out given the movement at many North American universities toward a corporate business model. By allowing work from media labs to leak out into the high-tech world, ideas and ethos other than those of commerce could become visible. Ideally this would support citizens’ capacity to think reflexively, which is “a central requirement to the functioning of a vibrant democratic culture” (Ulrich Beck et al., as quoted in Hassan, 102).

A post-humanities lab would be a humanities-based lab that takes into account the work of theorists who have rightfully sought to destabilize the human exceptionalism historically apparent in academic discourse (and culture at large). Writers such an Donna Haraway, Bruno Latour, Cary Wolfe, Katherine Hayles and several others have written about cyborgs, non-humans and companion species in the interest of promoting a more complex conception of the interconnectedness of all entities within and beyond the scope of human understanding. Some theorists including Haraway and Claire Colebrook have moved beyond or rejected post-humanism in order to shift away from the anthropogenic nature of the term, preferring to focus on the social and economic conditions that have contributed to global inter-species concerns like climate change which are not perpetuated by all humans equally across cultures.

I like to think of posthumanism as reaching toward what might go beyond all that “human” implies. If we can transcend what keeps us trapped within the contradictions of capitalism maybe we’ll have a shot at a post-“future” future.

Works cited

Bell, Gordon and James N. Gray. The Revolution yet to happen, Beyond Calculation: The Next Fifty Years of Computing. Peter J. Denning and Robert M. Metcalfe (eds.) New York: Springer,1997. pp. 5 – 32. Print.

Brand, Stewart. The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT. New York: Viking Penguin, 1987. Print.

Ghosh, Amitav. Petrofiction, The New Republic, March 2, 1992. pp. 29 – 33. Web.

Hassan, Robert. The MIT Media Lab: techno dream factory or alienation as a way of life? Media Culture Society. Vol. 25, no.1, pp. 87-106. 2003 doi: 10.1177/016344370302500106. Web.

Kolbert, Elizabeth. No Time: How did we get so busy? The New Yorker. May 26, 2014. Web.

Schulte, Brigid. Overwhelmed: Work, Love, and Play When No One Has the Time. New York: Harper Collins. 2014. Print.

Additional Reference

Barbrook, Richard and Andy Cameron. The Californian Ideology. Science as Culture. Vol. 6 Issue 1. 1996. Web.

The post WELCOME to the Techno-Dystopian Future! appeared first on &.

]]>The post We are All ‘Super Slick Salesmen’: A life as a living historian in the retro-utopia, or, I have an amazing post-apocalyptic bug out team – probe on the MIT Media Lab appeared first on &.

]]>Most of the world today runs on ‘fixed-term contracts’ (Barbrook, 1995, p. 2). Long gone is the notion of staying in one job or company for an entire career. When I began my career as a historian, Mulroney had decimated the history staff at Parks Canada, and many of the community museums in Nova Scotia were only seasonal. I knew early on that I needed to diversify my skills and always be ‘on the lookout’ for the next contract. There was no “guarantee of continued employment” (Barbrook, 1995, p. 2), there wasn’t even a guarantee of summer employment! All that aside, for the most part, Nova Scotians have put their ‘big girl panites’ on and figured out how to live a meaningful life. Like Europe, we understand the need “for an enlightened mixed economy” (Barbrook, 1995, p.8). There is no job that is deemed ‘too menial’, in fact many of the people behind the counter at Tim Horton’s have degrees of higher learning, some of them multiple. The running joke in my family has long been ‘Dr. Grant to the centre cutting table’ because to return to Nova Scotia may mean a return to working at Fabricville.

So what’s a historian to do?

In Robert Hassan’s article “The MIT Media Lab: techno dream factory or alienation as a way of life” he asks “what are some of the possible social, cultural and ontological consequences of ‘being digital’ within a hypermediated digital ecology of interconnectedness” (Hassan, 2003, p. 89)? Hassan tells us that the MIT Media Lab looks at ‘Sociable Media’ and how people percieve each other in a networked world, and the ‘Digital Life’ looks at connections between ‘bits, people and things in an online world’ (Hassan, 2003, p. 90). As I have mentioned in class before, part of my life is spent online interacting in online history communities. This is not really all that different from most people’s lives. Everyone has online communities that they frequent. What is a bit different for me, is that the online world is also my work world. “[T]he ‘real-time’of the online environment [has] become the ‘real-time’ of [my] everyday life” (Hassan, 2003, p. 90). My peer-group has come to realize that we can use technology to create a space for working, sharing research, and networking with historians and museum sites all over the world. We have found a space that is between the ‘good and evil’ of technology, in that we all use it, begrudgeonly for some, but that it can be a useful tool for us to develop the networks we need in order to remain in the history field (Hassan, 2003, p. 91). For many of us, dabbling in webpage development was just too cumbersome a thing to maintain. Facebook though, proved to be an easy interface to use. Add to this many blogging forums that we could publish in and hotlink to facebook, a network could be formed. In a similar fashion to LaTour’s laboratory of a couple of weeks ago, we are able to read other’s research findings, share and collaborate on new articles, and be in a creative space together, even though we may physically be thousands of miles apart. A cocktail party in our network would have to be done over skype, with each of us sitting in our own home offices, probably over coffee instead of alcoholic drinks. “Media has become critical in popularizing me as a person in the historical community” (Hassan, 2003, p. 92).

So my work life and personal life have become blurred into one. My online prescence is strictly developed to provide ‘good press’ (cited in Hassan, 2003, p.93). I am constantly reading about the eighteenth-century and its fashion, I am hoping to soon fully contribute to that discussion instead of just the occasional comment. My own trips to the past in the form of re-enactment are not only sales trips in that I am still making clothing for interpreters, but also research and networking trips as I learn of new pieces of extant clothing that I will want to study for the disertation. In both instances, I have to be ‘on my game’. Unfortunately though, despite my offering a ‘commercially viable product’ (Hassan, 2003, p. 93), I am not being paid unless I have provided an article of clothing as part of the exchange. I am still being paid for what I do, not for what I know, and that tends to relate to a lower dollar amount. Hassan tells us that “ICTs have flooded the lives of many within the advanced economies, that it is increasingly possible to speak of life being conducted within an information environment, an informational ecology” (cited in Hassan, 2003, p.95). How to earn a living from this ‘interconnectiveness’ will be the question on many historians lips before too much longer.

I will admit that I am extremely privledged to be who I am in this world, an historian who is not employed in the traditional sense, a graduate student. If it were not for my husband’s steady job, neither of these parts of my life would happen. I would be that struggling, retail sales associate at Fabricville, cutting your fabric, asking you what you are making, and if you need thread (questions we all have to ask, not that we are interested). I would not be sitting here at the computer thinking philosophical thoughts about ‘interconnectiveness’, I’d be worried about paying rent and buying groceries. These two things are still in the back of my mind though, because I have been that retail sales associate. And so this past week, along side my philosophical ramblings, I have been carrying out a time honoured tradion of processing the Fall harvest for consumption during the winter months. Alongside my friends in other parts of New England and the Maritimes, I have been making pickled veg, filling my freezer with other freezable vegetables and meats. If you live in an area where there are farms and farmers, food tends to be cheaper right now than any other time of the year. Also, since I have just received my term disbursement cheque, I have money. Money that was almost entirely spent on food for the winter months. Other friends of mine are processing their flock of chickens and turkeys, others still have gardens full that need to be ‘put up’ for the winter. Next summer, I too will have a garden full of things that we can eat. This summer was a write-off, as we did not move here until mid August, instead of the first of June as we had originally intended. I have other friends who are now finishing up their summer employment and are getting geared up to begin Winter projects for themselves, or to suplement their income producing items for museums trying to use up budgetary money before the end of March.

By now, you will have noticed that I haven’t cited the Brand reading. Having tried to obtain a copy of the book to read, I learned that it is not available as an ebook (technology), nor, despite there being several copies available, is it available for shipping until after christmas, unless I sign up for a costly Amazon shipping package that I will never use. In the meantime, I have been reading about the MIT media lab through other sources. I have been thinking about technology and how it was supposed to make our lives so much easier. One would think that by now, most books of this sort would be available as ebooks. My mum devours fiction now only as ebooks or audio books, which saves our bookshelves for books on art and topics that we are constantly researching. And then I think about what would happen without technology (there was a recent fiction novel about a post technology state and how re-enactors were able to build a new society, it was the SCA, but the skills are similar). I still wouldn’t be able to read an ebook entitled The Media Lab:Inventing the Future at MIT. I have been thinking about the community I have become a part of through the internet. How I would miss those friendships that I have developed. Hassan informs us that the time-space compression that technology provides was part of the acceleration of modernity, centrally connected to capitalist development. He explains that tech has changed the lives of many people in profound ways on a macro level (Hassan, 2003, p. 102). But what of the micro level? My own life would change without technology, certainly. I would have to think harder about the micro of daily life. How important a good cooking fire is; that hot water is a chore and a blessing when it doesn’t come from the tap. But then I think of the things that I know how to do, the knowledge that has been passed down to me from my parents and grandparents, the knowledge shared amoungst my peers. Daily life would be harder, but livable.

Especially if we up and moved again, to be closer to our friends, our post-apocalyptic bug out team.

Works Cited

Hassan, R. (2003). The MIT Media Lab: techno dream factory or alienation as a way of life. Media, Culture and Society, 87-106.

Richard Barbrook, A. C. (1995). The Californian Ideology. Mute, 1-8.

Works Not Cited

Brand, Stewart. The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT. New York: Viking Penguin, 1987. Chapters 1, 6, 9, 13.

Post Script

Last week I wrote a whole other probe about tech and how I live my life with tech, but still do a lot of non-traditional, low tech things at this time of year. That my life is a balance of tech vs. non-tech, leaning towards the non-tech. I was missing the last readings, from the Brand book though, and even commented on how my inability to find those readings ticked me off. This is why…

Thursday, before class, I went in to the Library and found a hard copy of the book. Yes, I could have done this right from the beginning, but I was told ‘just go on to google docs and look for the readings’. Having done that, I really could not find the readings. Further searches informed me that there was ‘no electronic format’ of this book, but that I could buy it from Amazon for the low-low price of one cent. I thought, ok, for one cent, that, even with shipping costs wouldn’t blow my budget. I could do this. I wanted a hard copy, printed out anyway, so that I could make my comments in the margins and highlight the hell out of it. You really can’t do that with a library book, the librarians kinda frown on it. The problem was, with regular shipping, the book wouldn’t get to me until February, unless I bought into Amazon’s expensive ‘free’ shipping program, Prime. I could get six months free trial and then cancel without being charged. Well two of my friends have fallen for this trick and have been charged, and have had a difficult time getting out of the contract, so I was hesitant…and so, I went to the library.

The thing is though, this book is about tech that was being developed 30 years ago. Think about that. Thirty years ago, I had no idea what the internet was. No idea what email, or list serves, or even really what a computer could do. Thirty years ago, I had just written my first computer program, in school, one that made a turtle slowly walk across a bar of music that made the notes play as he passed over them (paintbrush) (Brand, 1987, p.96). This was four years before I would know about something called the intranet, four years before my family would own ANY kind of modern tech. Hell, we had only just gotten a microwave!