The post Concordia’s Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling appeared first on &.

]]>I recently had the opportunity to visit The Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling, located on the tenth floor of the Library building. It was interesting to continue to look at spaces in Concordia that not only incorporate technology in their work but recognize it as part of the human relationships that are essential to their research. I was also interested in how much of the work that is done at the Centre expands beyond it, into the many community projects that the Centre is involved in, and how this research space is really constitutive of innumerable, unexpected spaces in Montreal.

AML: My name is Aude Maltais-Landry, I’m the associate director here at COHDS since this August, so I’ve been an affiliate for quite a few years, as a student, and I’m new at the position of Associate Director.

JB : Hi Aude, I was wondering if you could give me some background information for those who may not be familiar with the Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling. How did it come about and what is the goal of the oral history centre?

AML: The centre was created in 2006; we’re actually going to celebrate our 10th anniversary next year. The Centre was part of an initiative to build research units at Concordia University, so the idea was to have research-based projects, using oral history as a tool to tell alternative stories, I’d say, counter-narratives, to speak broadly, and using digital media to record, collect, and disseminate those stories.

The centre has always had a very community-based practice, as well, so of course it’s a research unit within an academic context, but we have a structure by affiliation, and we welcome affiliates who are independent researchers, community affiliates, or artists who are also doing work that connects with oral history or digital storytelling. One of the big projects that happened here was CURA, which is Community-University Research Alliance, that ran from 2006 to 2013, that was called Montreal Life Stories, and we collected interviews from Montrealers who were displaced by genocide or war, or other persecutions that were violations of human rights.

That big project really set up the basis of what we do, working closely with communicates using what we call shared authority, so the idea of researchers and interviewers, interviewees, working together, collaborating closely in how to record the stories and how to disseminate them. This is really the core of our methodology of our ethics; I would say, as well, this idea of the close connection with the people that we’re interviewing.

JB : I was wondering , what kind of technology does the centre use in their research? Is it only audio, or is it visual as well?

AML: It really depends. Often, we will ask the person if they want to be video-taped or not. Some projects do video-tape, some won’t, and some interviewees don’t even want to be audio-recorded, so then it’s only handwritten transcriptions. That’s for the collection, let’s say, for the interview. For the dissemination part, then we use a multitude. There’s a strong connection because of our arts-based affiliates and to the fine arts faculty as well, so in the course of that big project, the Montreal Life Stories, there were theatre performances and playback theatre, using those stories. We also did an exhibition at the Centre D’Histoire de Montréal, so really bringing the stories into the public space, into the museum.

Other digital tools are the audio walks from the Canal Lachine and Pointe-Saint-Charles, so the stories are edited into a piece, and you put it on your headphones, and walk through the neighbourhood, following a little map, and then you hear those stories about how the neighbourhood changed. It’s really using both digital and non-digital tools to try to go further and touch a variety of people. The digital aspect is not always predominant.

JB : It seems like there is a strong interdisciplinary prerogative at the Centre, for example, would a communications or film student work with the oral history centre, using their own techniques to make different representations of history?

AML: Yes, there’s really a variety of students from a variety of disciplines, and faculty members, there are actually from some from the English department, doing translation studies. We have a recent affiliate from medicine. It’s not a field that you would expect to find oral history within, but if you’re thinking about questions of health, how people perceive their health, their stories about health and healing, and things like that, it can touch a variety of disciplines.

People are encouraged to bring in their own tools, and I think that what we share is this methodology of collaboration and always based on the interview, and based on the subjectivity. Both the interviewer’s subjectivity, but also the interviewees, and being conscious that, with those two subjectivities, we’re trying to build a story, and finding common ground between those two.

JB : Do you find that there’s any challenge in that kind of relationship with an interviewee, because it is on a personal level, do you think that there are challenges in balancing the work with the personal aspect of the relationship? Because you mentioned ethics, I was wondering if researchers try to stay objective or is there a perceived need to be objective?

AML: I think that there are two parts to the question. This idea of subjectivity … and I think oral history is contested by some historians, who find it too subjective, in a way. I think we view ourselves as part of a current trend which is to be transparent, so, stating who you are, what position you’re talking from, doesn’t make your work less valuable, but then it’s just more honest. In a way, I think that we’re not looking for objectivity. Broadly. I hope nobody gets frustrated when they hear me say that, but I really think that there is also a commitment from the people here to a broader goal of social justice, I would say, of hearing the voices that are not heard otherwise, so I think that we don’t view objectivity as being a core value. That doesn’t mean that we don’t have a strict methodology, or that we don’t follow guidelines and principles and research ethics. It’s a different take on that.

Regarding the relationship with the interviewee, this is the object of many debates and many questions. Can you be too close to a person? How would that influence the interview? I think there are, again, a lot of reflections around those questions, and the fact of being very close, for example, interviewing a member of your family, brings in some things, and then also prevents you from accessing other things, because of the previous relationship that exists. Again, there is the question of transparency and being honest.

JB : In some ways I think you could argue that it’s impossible to be entirely objective anyways, and kind of working under the assumption that you are might lead you to just be biased in another way.

AML: Exactly. So I think we kind of take the stance that we are coming in with our own subjectivity, and how do we go from there? How do we still make something meaningful? How do we still take into account different points of view and divergent perspectives? Still keeping in mind that we are listening to those stories and we are affected by those stories as well, so it’s really building on this relationship.

JB : I just wanted to ask about the space itself. What kind of things go on in this space? Because I wrote to Stephen High and he said that a lot of the actual interviews go on outside the centre.

AML: So we have two main spaces, one with the main lobby, with different work stations, so people come there to work on one of the computers. We also have a small archive room. There’s another room where we have the equipment, and another few computers where people can work more quietly. There’s a room with two projectors that was our main seminar room, let’s say, up until last year. The other part, on the other side of the corridor, we have this big room that we’re in that was just renovated into this kind of conference space. And then a small interview room, where people, affiliates, can come in and do video or audio interviews.

Again, most of the interviews will take place at the person’s house, or another location that they prefer. Very often we will leave to the interviewee the choice of the location.

JB: What are some of the challenges with working with oral history? Or working with digital mediums as well?

AML: I would say that some of the challenges are the archiving of those materials, because working towards a digital archive raises a lot of questions about confidentiality, of access to the interviews, security questions … so, this is something that we’re moving towards, because we have a huge collection here, but it’s not that accessible to the wider public. People can come here and ask us to listen to whatever interview they want, and then we go through a process and see if that interview is open to the public, and most of them are, so in fact there is a huge collection here that everybody could come and consult, but it’s not that well-known yet, so how do we make that public?

JB : Are there any challenges specific to using digital technologies?

AML: Somehow we have this feeling that digital is easy to manage and to access, but then with interviews, with sensitive issues, you cannot just drop it online … there are other issues to keep in mind. I would say that that is one of the big challenges, and also, the speed to which the technology changes, the feeling of having to adapt, always, to things like websites or platforms that are not necessarily meant to be long-term depositories, so how do we reconcile these outcomes, these works, let’s say, with longer-term preservation of the content and the stories?

JB : That’s something we discussed, actually, in our class, because we were saying how digital technology does create a greater sense of accessibility, but at the same time, when you want to preserve something, it’s not as good as text, which you would think would be transient and easily destroyed.

AML: Paper is actually the easiest way to preserve, and I remember we had this discussion about archiving for all historians, and hard drives have a lifespan of like 5 to 10 years, so if you have everything on hard drives, every 10 years you have to transfer everything. This is just insane, you don’t want to think about that. I think that the digital aspect is full of challenges. Full of possibilities, but it also brings in a lot of challenges.

JB : What do you think that the centre itself gains from the community interaction, in terms of your work?

AML: I would say that the community has goals and objectives, and working with the community allows the research work or the academic work to be more connected with priorities. I think there is a very easy tendency within the academic world to kind of self-suffice ourselves with very intellectual theories, things that are very interesting, but that can be a little disconnected to what’s actually going on. Again, if I think back to that big project of Montreal Life Stories, it was really the ideas of; who are these people, living in Montreal, that we don’t know, and we don’t know their stories, and they’re part of our community, and how can we make their voice heard? Somehow? Working just within the University circle … you never access that, as a researcher. You’re kind of, in a way, restricted. I think that in very broad terms, I would say that that’s where we benefit, in building a research that’s more meaningful, for society, for communities, in general.

JB : It’s a chance to also apply the very things that you’re studying instead of just studying them?

AML: Exactly. What happened through the Montreal Life Stories project is that we integrated people who were not from the academic world and who are now doing PhDs so that they really became part of our community of research, and so that’s very strong, because they come in with a different point of view or a different perspective, and they bring that into the research, and that’s really enriching, I would say.

JB : That’s great. Thanks for your time.

NB: Aude informed me that there are many interesting workshops and events offered by the Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling. For details and how to sign up, visit the centre’s website here.

The post Concordia’s Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling appeared first on &.

]]>The post Embodied Space: The Webster Library Transformation appeared first on &.

]]>The Webster Library Transformation is underway and in the University’s postings about the work being done, the word ‘renovation’ is conspicuously absent possibly because it carries connotations of disrepair, age and maintenance of an old system. Maybe that’s also why it’s being touted as a “next-generation” library, which makes a kind of avowal of the timeliness of the library but also sounds like the unveiling of a new IPhone.[1] It’s similar to the previous version but somehow entirely life changing, transformative. It should not only bring us into the present age but it should project us into a time beyond our own. The library reprogrammed as scholastic utopia. The language used to describe the library’s changes is utopic in this sense that through innovation we will be taken into a new space, a hitherto imagined space that brings us not only into a different physical location, but projects us into a different conceptual space. I think the choice of the word transformation is apt and that the library will not only change the way we work and produce work as students, but as I would like to explore in this probe, the library transformation reflects and is an articulation of an already occurring shift in the way we conceptualise knowledge, the creation of knowledge and the identity of the student.

The Second floor

My preferred study space has always been the carrels (I prefer ‘cubes’) in the silent reading zone of the second floor along the windows that look down on Bishop street. The carrels are designed for the kind of individual writing work I need to do. The partitions separating each table and chair connect each student but also shields them from each other’s view. The walls act kind of like horse blinders or ‘blinkers’ as they are sometimes called, blocking out potentially distracting stimuli and directing the gaze front and centre. Sometimes I lean forward for maximum immersion or back to escape the feeling that I exist only within a word document. In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard’s meditates on corners, describing this type of space fondly as a “half-box, part walls, part door” (137) a space whose construction ensures immobility and allows us to “inhabit with intensity.”(xxxviii) Bachelard claims that the only we learn how to do this by occupying these corner spaces where imagination is seemingly everything. For me this silent, ascetic method of work and student has been part of the identity of an English student. But it can also be isolating. I wonder if my work sometimes reflects the circuitous trains of thought going on in my conceptual space or the narrowness of my work space. In I wonder if I am ‘blinkered’. I can’t help but think there is something like this going on when I am cloistered in my cubicle with my texts and my lecture notes trying to construct something of value. If the texts, the tech and the Profs are actors that influence our work then why not the spaces we produce our work in as well? In looking at the library transformation I began to see how a complex set of relations between people, objects, space and time can perform or express ideological work that informs the academic work being done at the University.

“Space that has been seized by the imagination cannot remain indifferent space subject to the measures and estimates of the surveyor.” (Bachelard, xxxvi)

The Third Floor

As I entered the new floor of the Webster library I was sceptical, I liked my claustrophobic little cube. I had only seen digital projections of a modern looking near-bookless library populated with ghostly students. Going up to the third floor was an ambivalent experience. I couldn’t help but be struck by the vast improvement in overall aesthetics of the third floor. The lighting was bright but soft, the lines of the furniture and shelves clean and new and the colors were not stale and drained of life. And yet the territory is slightly bewildering. Walking through the library I noticed the main difference between the second and third floor is a more open concept which gives the feeling of spaciousness although the study spaces are as close or closer together than in some areas of the second floor. Maybe this is an illusory distinction caused by the partitions in the old carrels, which have the effect of creating a bunch of little microcosms of student space. The library transformation was borne partially from a crisis of space, so it will be interesting to see how the individual, somewhat bulky space of the carrel is re-imagined.[2] This ties in with the second big difference: visibility. On the third floor you are always visible to everyone around you. The room is bounded by two glassed-in silent reading rooms with completely open tables. The workspaces are individual but communal at the same time. In between these rooms there is an open concept study area with ikeaesque tables, chairs and sofas. Talking is permitted, some students work alone along the wall looking down into the library building and others work in groups around the tables writing figures on a whiteboard. In the middle of the room there are three big glass rooms that resemble aquariums that contain groups of students working together.

For the library to do the work of a library, it must be constructed around clear delimitations. The different configurations of space must prescribe different types of behaviour. The more ingeniously these spaces are designed, the less visible the work being performed becomes.[3] The traditional library job of shushing has transformed from a slightly Orwellian image of a woman pressing her finger to her lips to an androgynous grinning emoji type symbol. Library Special Projects Manager Brigitte St. Laurent-Taddeo was kind enough to show me around and informed me that next to space two of the biggest concerns of the project was improving light and addressing noise. Concordia even hired an acoustician to find out how to promote a quiet space. The ingenuity of this floor is that in addressing the issue of light by replacing walls with glass, the visibility of the students seems to make them more prone to self-monitoring their noise levels. Even in the collaboration space students speak in hushed tones.

In “Of Other Spaces” Foucault describes sanctification of space as “inviolable” oppositions embedded in the space itself. These oppositions of silence and noise, inside and outside, together and separate are of paramount importance to the library and the new floor’s construction makes us those (almost) perfect little door closers. I would argue that the quality of a library depends upon its status as a somewhat sacred space, where these rituals of work, these “rites and purifications” (26) have to be observed to occupy the space and make way for the production of knowledge. “Heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing which both isolates them and makes them penetrable.”(26) The visibility of the student at all times allows us to perceive the needs of the other student and our own interest in respecting them by being silent. When the walls of the carrels are removed, we do the work of the walls. The design of the room demands that we keep out of each other’s workspace.[4] Transparency has also been a factor in the construction of the new library spaces through the Webster Library Transformation Blog. Students are now more aware of the changes made in the configuration of space while it is happening and encourage student input. This is also indicative of the kind of student of the new library, simultaneously and seamlessly utilizing virtual and physical space and making them communicate and improve upon each other.

Perhaps this new mode of thinking and producing transparently betrays the movement from one kind of student to another, but also another way of seeing the pre-existing connections between ideas, people, disciplines and techniques that can encourage innovation and understanding. Transparency could do away with the opportunities for glitches to hide in the system, to do away with biases of knowledge and make it easier to revise and critique our thinking. In Star’s “The Ethnography of Infrastructure” we have seen how transparency is arrived at through failure of the system and crisis. The library transformation came about partly from a crisis of space but also made visible the infrastructure of knowledge production. The transformation is also an opportunity for each tiny decision to nurture and influence the changing academic environment in its uncertain and hybrid form.

“In the everyday world, it is of shattered, scattered sacredness that we must speak […]” -Marc Augé, “An Ethnologist in the Metro.”

Naming is also important to note. The reading rooms in the third floor are named after countries namely, Kenya, France, Netherlands, Vietnam and India. In Marc Augé’s study of the Paris metro he notes the way that the historical names of the metro stops have shifting significations for different users and generations of users.[5] The naming of the reading rooms eschews the local in favour of the global. Library Special Project Manager Brigitte St. Laurent-Taddeo was kind enough to show me around and explained that the choice of countries corresponds to research done on the cultural backgrounds of the student population at Concordia. She also mentioned that the naming has not gone unnoticed by students and they’ve taken to referring to the rooms by their international names. This is indicative not only of the diversity of the students but also of the widening of scope from the local, historical to the global and mobile. The West is potentially dethroned as the priveledged centre of knowledge production. Foucault argues that “The museum and the library are heterotopias proper to Western culture of the nineteenth century.” (26), however the twenty first century sees the access to that wealth of knowledge broadened by our access via digital archives which makes us mobile, living libraries. At the same time that certain rites have to be performed to utilize the space, there is a corresponding de-sacralization of the library as site of knowledge. A corresponding change in physical access to books may be coming as the library aims to make more space for student. That student also occupies a different kind of space emerging from the individual space of the lone genius to the public and social space of the “next-generation” library. There is no arcane knowledge in this space, or rather it has lost its position of power in favour of the everyday as the cultural ground shifts, hierarchies of knowledge slip, high and low culture is renegotiated. Moreover the process of how these valuations of knowledge come to be is made visible and studied. This change in the conception of knowledge might mean the disappearance of a certain type of scholar or simply the transformation of his work.

“In other words, we do not live in a kind of void, inside of which we could place individuals and things. We do not live inside a void that could be colored with diverse shades of light, we live inside a set of relations that delineates sites which are irreducible to one another and absolutely not superimposable on one another.” –Foucault “Of Other Spaces”

The stacks themselves are also a part of the transformation. The collections movement from the second to the third floor necessitated a paring down of the books. The task of ‘weeding’ removes from the collections all redundant, out-dated and damaged books and donating them to an archive or another institution. The out-dated books fascinated me the most, to imagine all the once relevant ideas in those books becoming artefacts is part of the process of knowledge making but still chills me but even to be wrong means one is playing a part in the creation of knowledge and that some can only hope to be a blip on the academic radar.[6]This pruning of material betrays the already apparent role of artefact, the books have been assessed by the decreasing frequency with which they are requested, and their unpopularity pointing to newer modes of thought; their removal is just the solidification of their non-agency. Although the library assures me that they never simply throw out books, I can’t help but wonder if anything is lost in the increasing digitization of documents. Increasingly, students can access information across different mediums and using new tools, which entail a different experience of learning.

The new library has also added two different types of spaces with the express purpose of showing work, The Multipurpose Room and the Visualization Room. Both rooms provide students with the use of equipment and space designed to share their projects. The inclusion of this room speaks to the imperative to have our work be visible so that others can interact with it. The use of a variety of techniques that crosses disciplines, allows different disciplines to perceive existing connections between areas of study. We see this at work in the MLab, as the different tools and theoretical lenses used take Joyce’s Ulysses beyond the English Lit stacks and seminars. It also speaks to the benefit of visibility in academia through the diffusion of work on blogs and social media. Once mostly a tool for mediating our personal lives, the growing authority of these types of forums allows work to traverse boundaries of academic prestige, defy categories of discipline and exist in experimental forms. And now to digress to another space…

Ninth Floor, Hall Bldg

An incident in the University’s history elucidates articulations of space, transparency, visibility, infrastructure, technology and access to knowledge.The Computer Centre Incident of 1968 was a student riot incited by allegations of racism directed at six West Indian biology students from a faculty member. After talks degenerated at a Hearing Committee formed to investigate the charges, two hundred students occupied the computer centre in the Hall building. Over the next two weeks negotiations were carried out almost to the point of a compromise but failed just as half the students left the protest, the argument reignited and the remaining one hundred students carried out their threat to destroy the computers, causing extensive damage to the building as well. There are many things that are interesting about this story is the way the public space is contested and shown to be already a part of the political and ideological struggles at the university. The student’s choice to occupy the computer centre and threaten the technology in order to leverage their claims shows that they perceived where value and power was situated spatially in Concordia. What is demoralizing is that they wanted recognition of injustice so badly that they would destroy the very spaces and objects that were integral to their own research and identity as students. This incident resulted in the arrest of students, the eventual reinstatement of the accused faculty member and millions of dollars in damage. The computer lab is still on the ninth floor of the Hall building and no traces of the riot remain but the conflict resulted in the re-organization and institution of student representation and a restructuring of policies and codes that govern university life. Interestingly, the Paris protests were happening at the same time, students occupied the streets and took to turning over cars when they couldn’t get their institutions to cooperate. The ideological changes though not completely effected, can be communicated through violence to space. At the same time, the anarchic violence to space is an attack on an expression of ideology, power and forms of social ordering.

Today space at Concordia is increasingly heterogeneous and political and ideological action is intrinsic to the construction of space. If we look at other spaces in the University, memorials, cafes, corners, thresholds, we can see how structure and design can redistribute power to the students. There are as many struggles, stories and resistances as there are spaces in Concordia. The library transformation’s policy of transparency and ongoing construction gives us the opportunity to contribute our own ideas and opinions. Even better the library is an extension of the classroom; part lab, part experiment, a heterotopia that belongs to everyone and no one.

[1] Webster Library Transformation Blog

[2] “At present, only .57 m2 of space is allocated for each full-time equivalent (FTE) student. This ranks as the lowest space per FTE among comparable Quebec and Canadian university libraries.”[2] https://library.concordia.ca/about/transformation/

[3] See Star’s The Ethnology of Infrastructure.

[4] Law, “Notes on the Theory of the Actor Network: Ordering, Strategy and Heterogeneity.” Concept of strategies of translation improving network strength. (6)

[5] Auge, “An Ethnologist in the Metro” (275)

Works Cited

“Webster Library Transformation.” Libraries. Concordia University, 5 Mar 2015. Web. 1 Nov 2015.

“Collection Reconfiguration Project: One large step towards a healthy collection.” Webster Library Transformation. Concordia University, 2 Feb 2005. Web. 1 Nov 2015.

“Our vision for the Webster library.” Concordia University, 19 Nov 2014. JPEG.

“Computer Centre Incident.”Records Management and Archives. Concordia University, Feb 2000. Web. 5 Nov 2015.

Augé, Marc. “An Ethnologist in the Metro.” Journal of the Twentieth-Century/Contemporary French Studies.

Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. Boston: Beacon Press, 1958. Print.

Foucault, Michel, and Jay Miscowiec. “Of Other Spaces.” The Johns Hopkins University Press. 16.1 (1986): 22-27. JSTOR. Web. 1 Nov 2015.

Law, John. “Notes on the Theory of the Actor Network: Ordering, Strategy and Heterogeneity.”Center for Science Studies Lancaster University. (1992): 1-11. Web. 5 Nov 2015.

Sayers, Jentery. “The Long Now of Ulysses.” Maker Lab in the Humanities. 21 May 2015. Web. 7 Nov 2015.

Star, Susan Leigh. “The Ethnography of Infrastructure.” American Behavioral Scientist. 43 (1999): 377-389. Sage. Web. 2 Nov 2015.

St. Laurent-Taddeo, Brigitte. Personal interview. 11 Nov 2015.

The post Embodied Space: The Webster Library Transformation appeared first on &.

]]>The post The Media Lab as a Leather Bar appeared first on &.

]]>The Village, a Gay Titanic

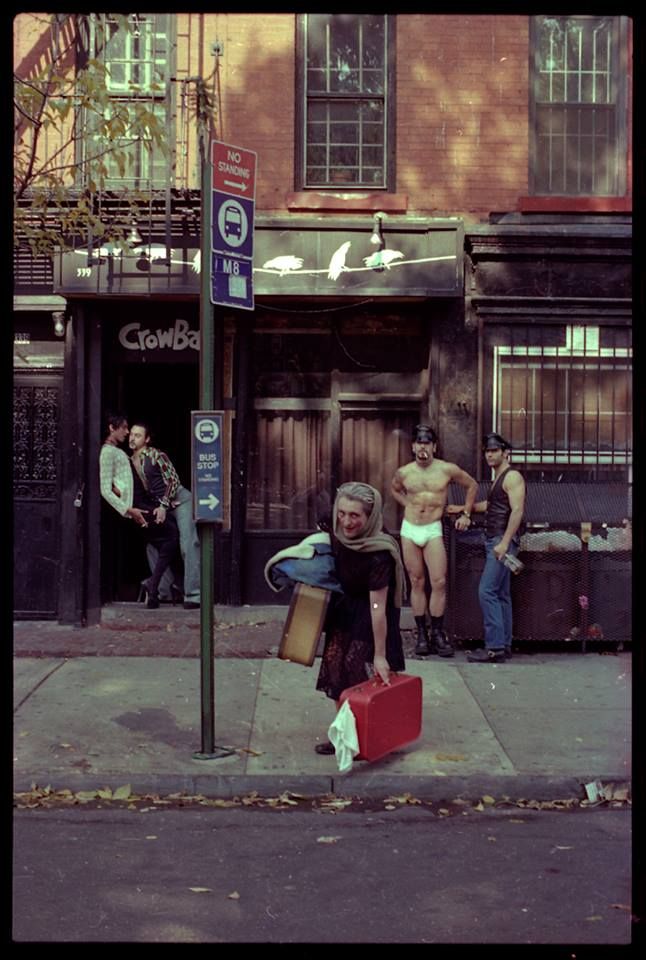

Michel Foucault’s concept of heterotopia, grounded as it is in our course in the idea of the media lab, made me think of a major concern I have when it comes to my scholarship on city space. Specifically, it made me think of the gay village, and Montreal’s Gay Village in particular, as a kind of utopia, or heterotopia. In her book on Walter Benjamin and The Arcades Project, The Dialectics of Seeing, Susan Buck-Morss writes about the arcade as reflective of bourgeois utopian dreams through its references to commodity fetishism, prostitution, gambling, etc. The gay village is built on a similar kind of utopian idea of safety, freedom, and a particular kind of aesthetics.

Yet, Montreal’s Gay Village is failing. While centrally located and a tourist attraction, especially in the summer, businesses are closing all along Saint Catherine Street, bars are losing their younger patrons and the area is generally seen as less desirable to live in due to violence, homelessness and the economic median. The Village, with its aggressive (yet dwindling) consumerism that certainly defines it as both “gay” and a “village” (bathhouses, sex shops, leather bars, etc.), has become normalized, normativized and boring. Left on the margins of contemporary queer life in the city, I question if the Village might constitute a heterotopia if it fails to be contradictory or disruptive, to be the “other” space that excludes normality while emulating a particular kind of utopia.

Where does the Village fail? In “Of Other Spaces,” Foucault writes of the Middle Ages as a “hierarchic ensemble of places: sacred places and profane places […] It was this complete hierarchy, this opposition, this intersection of places that constituted what could very roughly be called medieval space: the space of emplacement” (22). While I would not go as far as to call the Village Medieval, there is something to be said about the fact that, in the absence of a vibrant activist or community-building impulse, the Village has been reduced to that of a shopper, and for this purpose banks on the idea of the “profane.” After all, porn theaters, bathhouses and leather bars are what today’s gay village is. Where it could have been the topsy-turvy place of the carnivalesque, it is not much more than the place of role-play. It is hardly “hetero,” and no one even bothers with the “utopian” part anymore. Certainly, one could speak of the Mile End as an alternative to the village as a reconfiguration of the antiquated idea of “villages” and “ghettos” in a more diverse dress (men, women and others; straights and queers alike), and a space that is queer/heterotopic by default. Otherwise, the dying gay institutions such as the bathhouse, or the YMCA, may betray a sense of heterotopia as deviation and ritual. If we pushed it, today’s village might be heterotopic in a similar way to a cemetery, not only in that it is a dying place, but also in the tradition of gayness as a death of sorts: in her book AIDS Literature and Gay Identity: The Literature of Loss, Monica B. Pearl posited that AIDS was not the first time that “loss, mourning or death” demarcated the gay population, but that it is a part of a larger tradition of interplay between gayness and death, either biological or that of innocence, of the heterosexual identity, of parental/adult authority, or of the natural order” (Pearl 8). Yet, in spite of this macabre, and mythical understanding of the Village, I am still not certain if the Village is the Foucauldian boat for Montreal queers.

The Street Between Four Walls

What of media labs, though? What kind of work can be done in them, especially in terms of urban studies? This is the kind of question that was buzzing around my mind as I thought about the Village as this fixed, inoffensive slice of urban landscape, and I couldn’t help but wonder if the media lab just might be the solution. When, at a round table on media labs, Prof. Darren Wershler spoke of the media lab as heterotopia, both material and imaginary, institutional (relating to, and being funded by a university, for example) and deviant (contained, removed from more traditional modes of knowledge production) (“What Is a Media Lab?”), I kept thinking back of the Village as a mythical project and a much more concretized reality. Would a media lab problematize, or transform, the Village in ways that the Village itself cannot? What would it mean to study the Village at such a distance – both physical and methodological?

If one were to create a media lab based on the study of space, what kind of objects would it contain? Maps, leaflets, flyers, advertisements, street signs, blueprints, coasters with logos of bars underneath… Yet, what would this all do? I am wary of the idea of the database, or the archive – they not only seem so antiquated, but they also seem limited and insular. A media lab, as a think tank, a heterotopia of ideas, objects, and circumstance would have to (re)arrange these artifacts and take them apart like LEGOs in ways that would disrupt and destabilize a place’s accumulated normalcy.

These objects would constitute different media, instances of different mediation of the city space that, in turn, would have agencies of their own. The media lab, then, would constitute a particular assemblage of media and methodology, with an agency unto itself. If, for example, its main three methodologies would fall into the fields of film studies, literature and art history as disciplines that have helped shape our understanding of a particular city space, then a process of curation would not suffice. These material or digital assets would have to then intersect methodologically as well as topically in order for the humanities student to create not a thesis, but an ideology: an overwhelming approach that would valorize certain objects over others, and to, as Jentery Sayers puts it, “yack about theory and process” (“The MLab: An Infrastructural Disposition”). In a decidedly alternative, more informal research space, the media lab’s job would ultimately be to create a kind of vernacular of talking about space (the Village, in this case), which for me constitutes the poetic crux of the thing: coming up with a different vernacular to talk about things that are vernacular to begin with – the city streets, desire and the quotidian. It is heterotopic to the max.

My two questions are as follows: How would one bring the study of space, and in particular urban spaces, into a media lab, especially considering observation and location-specificity of places as a traditional way of studying them? Would we resist the idea of curation of objects, or sorting them into databases, or would the media lab resolve the fixity of such an approach through some other methodologies? It is a similar question, I think, to Sayers’, when he asks, “What makes tactical media persuasive?” (“The MLab”) Furthermore, does a media lab have a shelf life of a gay village? Is it ever in peril of being fixed, or institutionally normalized, both in terms of its thesis and its methodology?

If a media lab ceases to be an “other place,” does it simply become a leather bar?

Notes

Buck-Morss, Susan. The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1989. Print.

Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces.” Trans. Jay Miskowiec. Diacritics 16.1 (1986): 22-27. JSTOR. Web. 10 Oct. 2014.

Pearl, Monica B. AIDS Literature and Gay Identity: The Literature of Loss. New York: Routledge, 2013. Print.

Sayers, Jentery. “The MLab: An Infrastructural Disposition.” Maker Lab in the Humanities. University of Victoria, 29 June 2015. Web. 05 Nov. 2015.

The post The Media Lab as a Leather Bar appeared first on &.

]]>