The post Big Fried Chicken Post-Mortem appeared first on &.

]]>Current State of the BFC

Gaming Hunger

Southern Expansion

Poulet Frit Infernal

BFC owes its name to a popular fried chicken restaurant that already exists outside of Minecraft. In Québec, the translation of KFC to the French is PFK, as in Poulet Frit Kentucky. With a little twist, I present to you a version of the BFC which was built in Morbihan, called Poulet Frit Infernal.

It’s powered by a Thaumcraft multi-block structure called the Infernal Furnace. The furnace not only produces fried chicken, it also produces chicken nuggets, a food item added by the Thaumcraft mod.

Calcifer, the fire demon held inside the infernal furnace, spits out cooked chicken and chicken nuggets at a leisurely pace. Thank you Thaumcraft or this would never have been possible.

Notes

- Other than the video game-specific rules inherent to Minecraft, the mLab server has socially-enforced rules, also called “local rules”, rules that players create within their own social groups, or by the server’s host. BFC’s interactions (as a project and as a digital structure) with some of these local rules was sometimes a bit rocky.

- It is interesting to see how players take to industrialization and automation. Some players shy away from it, perhaps because it makes the game too easy too fast (as if playing on “godmode”/creative mode). Other players spend all their time creating machines that never stop working. There are also ideological reasons against industrialization that have been carried over from the non-digital world.

- For more conclusive conclusions about the BFC and how it was built, you can also check out my slides here from a presentation on the topic last spring.

Bonus Section! Quotes from various mLab Players about BFC:

These quotes are from mLab players not attached to the project. I asked them if they would be willing to share a sentence (or more) on what they thought of the BFC on their server. These quotes are presented in no particular order, anonymously, and with some editing to preserve clarity. I thought it would be useful to catalogue these responses for posterity.

- I was personally disturbed by the ownership of the server that was displayed, and wanted nothing to do with the project.

- I think it’s an interesting idea. it fits with the spirit of factorization (making players’ life easier) on the server, however it never became part of the ecosystem. I think it’s partially because we [the server’s players] didn’t build it. Hired workforces built it and that didn’t blend organically with the “society” on the server. The group of people that play on the server are a liberal bunch who frown upon big corporations in real life and that translates to the game. This server is peculiar because we tried to take into account the NPC (non playable characters) and in that context, having a fast food restaurant mercilessly massacring chickens by the thousands is not something people will support.

- I saw it as literally nothing more than a slightly eyesoreish source of free murder-flavoured nutrition.

-

[On the subject of] the actual building and machine itself I don’t have much to say really. It’s kind of nice but also it’s really weird how it’s just an exact copy of an existing design. It ignores all the ways in which the mods on the server could make accomplishing the task easier or more interesting. What I thought was kind of weird was mainly these things: because the server was the site of this research project it raised some issues about where the ownership of the server rested and who was working for who, which only got more confusing as time went on as new people were hired and the server was taken out of the mLab, without the knowledge of the players or the original maintainer of the server. Because the server was moved to a new locked location, the server’s performance dropped, players stopped going online. Eventually the server was returned, but the entire ordeal seems illustrative of the way academia appropriates students’ work. [Because of all the issues with regards to the ownership of the server] I didn’t keep a super close eye on the project itself but it seems that undergrads were basically hired to build the fried chicken thing after a detailed blueprint [and] some of them hadn’t even played minecraft before? I’m not sure what the goal of the study was really, but I hope it wasn’t to study anything representative of typical minecraft play. You had people playing on the server not because they enjoy it but because it’s a job, and instructions can restrict the creative freedom that is kind of a big part of Minecraft. This is a super obvious example of alienation in the Marxist sense.

- I have only known the BFC as a ruin which makes it seem kind of legendary. I’ve been pillaging it for building supplies.

The post Big Fried Chicken Post-Mortem appeared first on &.

]]>The post A Squirrel Is Stuck Between An Ocean And A Hard Place appeared first on &.

]]>Approaches to AI in virtual systems and Minecraft

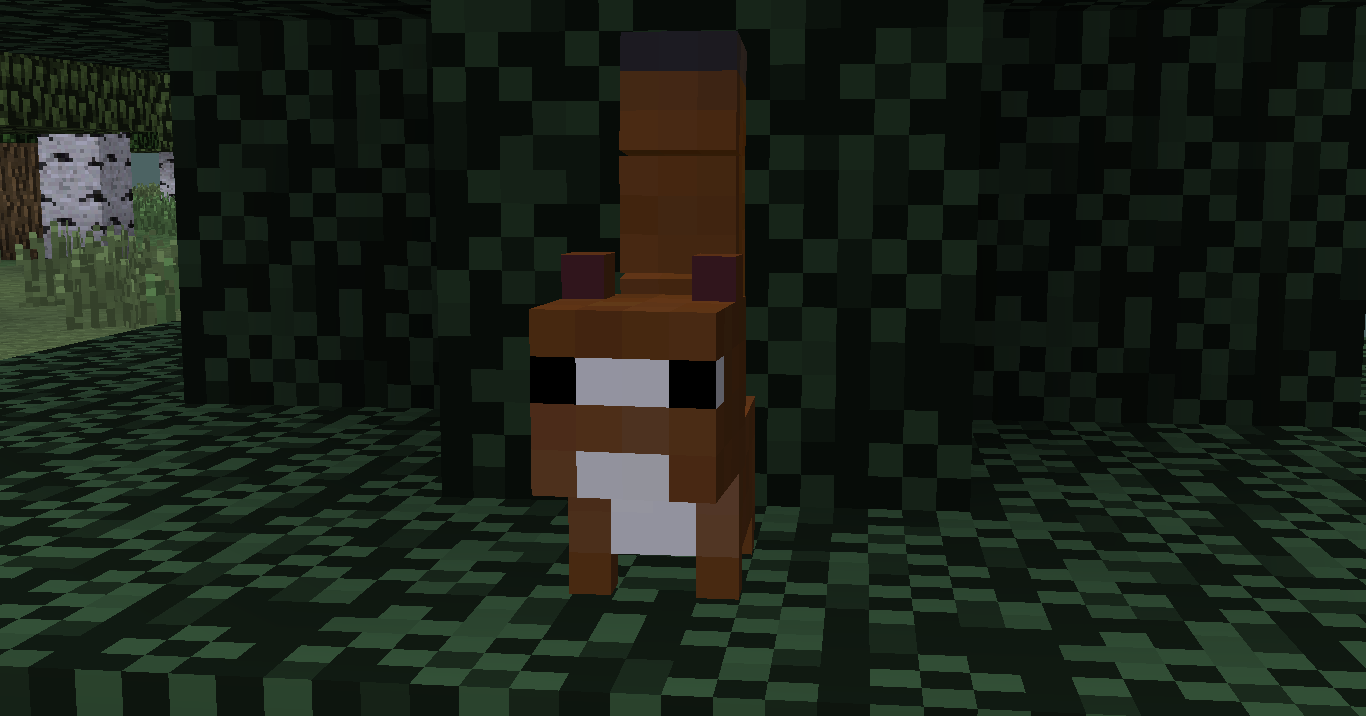

Yesterday, while wandering around the mLab and procrastinating between deciding to go to bed at a reasonable hour or stay up and work on midterms, I came across something I have seen many times in my Minecraft play. A small non-agressive mob was stuck between the ocean and a ledge on a cliff, with no means of escape. By small, I mean a mob that is smaller than half of a game “block” (Minecraft’s “standard” unity of measurement) and in this particular case the mob was a squirrel, a colourful addition to Minecraft’s bestiary from one of the mLab’s 130 odd mods. Either it spawned on the ledge or had fallen there, and because of its small size, it was stuck on the ledge, doomed to fall into the ocean if it tried to escape.

Thus the squirrel simply sat there.

In meatspace, or the real world, the squirrel would die of starvation if the squirrel had found itself on that ledge. Perhaps the meatspace squirrel would be motivated by some instinct to attempt to climb the impossibly steep dirt and rock cliff facade.

But in Minecraft, the squirrel is doomed to its fate until the system despawns the chunk of server land that this drama is unfolding upon. The squirrel is doomed to sit there on that ledge, ostensibly for as long as the server chunk is loaded, for the rest of time.

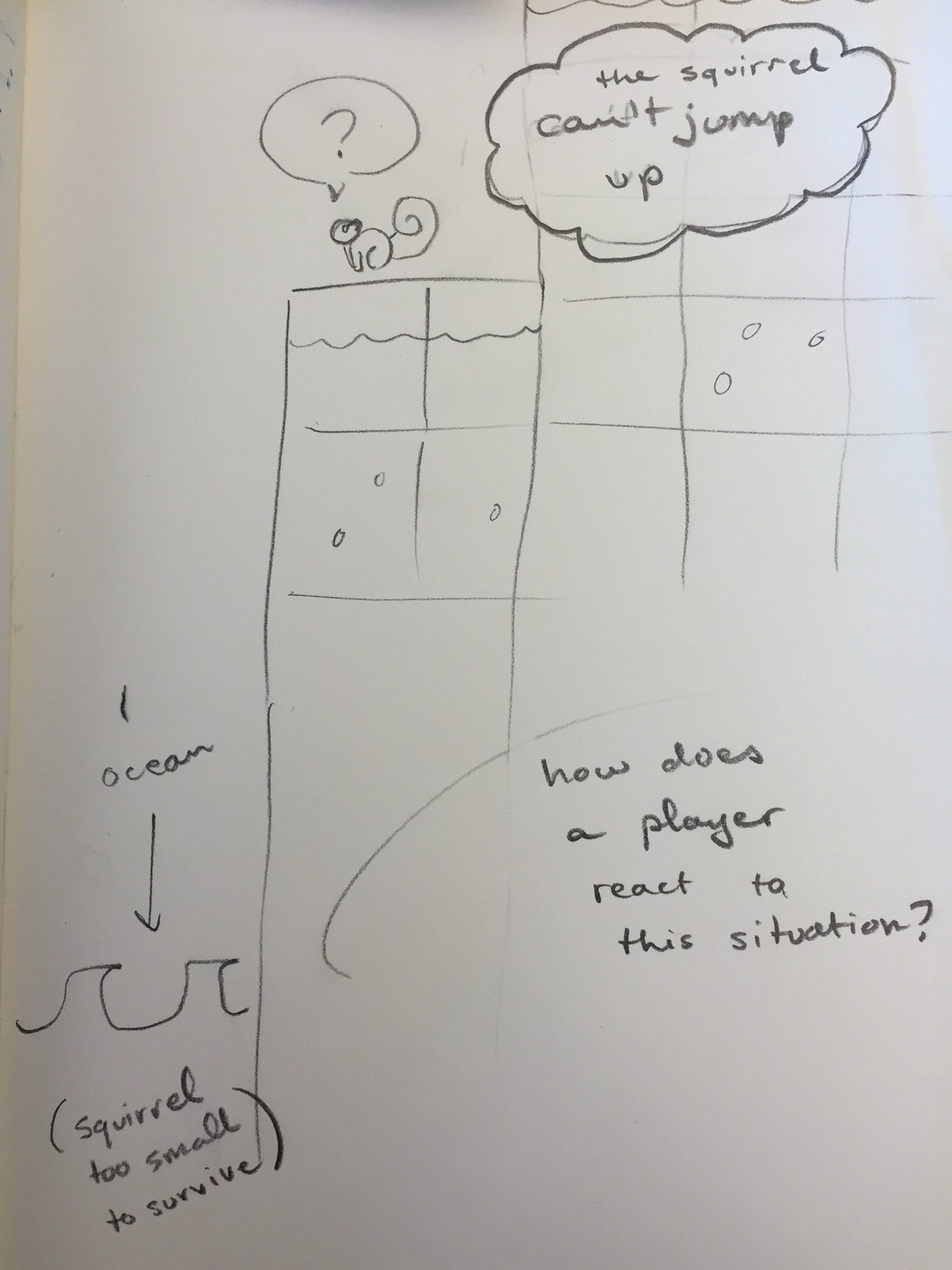

Because I wasn’t thinking of taking screenshots of the stranded Minecraft squirrel last night (sleep deprivation, tsk tsk) I decided to illustrate the situation for you with a sketch:

The squirrel is in a tough situation. As I was fluttering about the server, and I saw this squirrel, my immediate impulse was to dig a little path into the cliff’s rocky face, so that the squirrel could escape to the woods above and go about its squirrelly business.

Why would I do that? Why so much empathy for a Minecraft squirrel?

The squirrel, after all, is just an artefact of computer code meant to do things that I, as a human playing Minecraft, can interpret as squirrel activity. This, and its aesthetic, cue my brain into seeing a “squirrel” as the manifestation of a bit of computer code. Without my interpretation and visual interaction with the squirrel, is that bit of computer code really a squirrel, or just a bit of computer code? If no one is around to interpret the squirrel’s immobile waiting on that rock ledge as panic and despair, is the squirrel really in any danger?

From the perspective of the strip of code governing the squirrel’s activity, that squirrel’s activity makes perfect sense. The computer code has judged the situation and asserted: “There is danger in every direction, but right here is safe. So the squirrel object won’t move. Success!”

It is my interpretation that the squirrel is stuck, and because I think a squirrel should be frolicking about in the woods, I have this idea that the squirrel’s activity sitting on a ledge is somehow unsatisfactory. I am moved to change the circumstances and give the squirrel an opportunity to rectify its activity.

In an interview between filmmaker Gina Harazsti and Dr Darren Wershler (I was lucky enough to see a preview of the footage last week) professor Wershler asserts that the reason we care so much about “cute mobs” in Minecraft is because of nostalgia. We don’t care about skeletons or creepers stuck on ledges with nowhere to go. We are nostalgic about squirrels in Minecraft because we are nostalgic about real squirrels. Is it that we want to play out a fantasy as a human emissary to an animal society in danger? There’s a lot of writing on “cuteness” and its evolutionary function. Are we playing out real-world biases via nonhuman mobs in Minecraft – because the squirrel has a fluffy tail and is so small, are we confusing two very different nonhuman “creatures” – one of flesh and fur, the other an artefact of software.

SO CUTE AND FLUFFFEEEEEEEEEE

When artificial intelligence research and cognitive science were both in their infancy, a piecemeal approach was developed by some researchers who were hoping investigations of artificial intelligence would be a useful tool to reproduce “human” intelligence. In his report Intelligence without representation by Rodney A. Brooks, where Brooks describes research done at the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the paper asserts flat out: “Artificial intelligence started as a field whose goal was to replicate human level intelligence in a machine.” This original goal was gargantuan – but there was hope that in isolating the different “pieces” or components of cognition, we could replicate them with mechanical processes whose “brains” would be software. Brooks’ report was published in 1987 and as such presents a particular picture in time for artificial intelligence research – however I have found it interesting to compare some of the points he makes on the breakdown of artificial intelligence into units performing various functions, to the nonhumans of Minecraft.

I examined the points Brooks makes about artificial intelligence research concerned with making robots in the real world, rather than making software interacting in a virtual space. He mentions game spaces with the famous “blocks world” example :

In the late sixties and early seventies the blocks world became a popular domain for AI research. It had a uniform and simple semantics. The key to success was to represent the state of the world completely and explicitly. Search techniques could then be used for planning within this well-understood world. Learning could also be done within the blocks world; there were only a few simple concepts worth learning and they could be captured by enumerating the set of subexpressions which must be contained in any formal description of a world including an instance of the concept.

Brooks however criticizes the heuristic problem solving methodologies used in the “blocks world”, stating they are too simple for serious, epistemological artificial intelligence research. It is perhaps difficult to conceptualize what the “blocks world” was, as it was for me when I first started investigating it, and I stumbled upon SHRDLU – an early natural language understanding computer program. It is basically a programming software that learns to make “blocks” of concepts containing subexpressions. For instance, in a “blocks world” software, you could teach the software that chicken is a type of meat, and that meat is a concept “block” worth remembering for further interactions. An example from SHRDLU illustrates this:

Person: PICK UP A BIG RED BLOCK.

Computer: OK. (does it)

Person: GRASP THE PYRAMID.

Computer: I DON'T UNDERSTAND WHICH PYRAMID YOU MEAN.

Person: FIND A BLOCK WHICH IS TALLER THAN THE ONE YOU ARE HOLDING AND PUT IT INTO THE BOX.

Computer: BY "IT", I ASSUME YOU MEAN THE BLOCK WHICH IS TALLER THAN THE ONE I AM HOLDING.

Computer: OK. (does it)Person: WHAT DOES THE BOX CONTAIN?

Computer: THE BLUE PYRAMID AND THE BLUE BLOCK.

Person: WHAT IS THE PYRAMID SUPPORTED BY?

Computer: THE BOX.

Person: HOW MANY BLOCKS ARE NOT IN THE BOX?

Computer: FOUR OF THEM.

Person: IS AT LEAST ONE OF THEM NARROWER THAN THE ONE WHICH I TOLD YOU TO PICK UP?

Computer: YES, THE RED CUBE.

Person: IS IT SUPPORTED?

Computer: YES, BY THE TABLE.

Person: CAN THE TABLE PICK UP BLOCKS?

Computer: NO.

Person: CAN A PYRAMID BE SUPPORTED BY A BLOCK?

Computer: YES.

Person: CAN A PYRAMID SUPPORT A PYRAMID?

Computer: I DON'T KNOW.

Person: STACK UP TWO PYRAMIDS.

Computer: I CAN'T.

Person: WILL YOU PLEASE STACK UP BOTH OF THE RED BLOCKS AND EITHER A GREEN CUBE OR A PYRAMID?

Computer: OK. (does it)

Person: WHICH CUBE IS SITTING ON THE TABLE?

Computer: THE LARGE GREEN ONE WHICH SUPPORTS THE RED PYRAMID.

Person: IS THERE A LARGE BLOCK BEHIND A PYRAMID?

Computer: YES, THREE OF THEM: A LARGE RED ONE, A LARGE GREEN CUBE, AND THE BLUE ONE.

Person: PUT A SMALL ONE ONTO THE GREEN CUBE WHICH SUPPORTS A PYRAMID.

Computer: OK. (does it)

Person: PUT THE LITTLEST PYRAMID ON TOP OF IT.

Computer: OK. (does it)

Person: DOES THE SHORTEST THING THE TALLEST PYRAMID'S SUPPORT SUPPORTS SUPPORT ANYTHING GREEN?

Computer: YES, THE GREEN PYRAMID.

Is the computer software actually learning something? It certainly simulates the process of learning. It knows that it can 1) do an action 2) admit the action is impossible, or that it can 3) answer a question in the affirmative or 4) answer a question in the negative or state 5) admit ignorance. But if you taught the computer thousands of different concepts (cubes, pyramids, pasta, cookies, ducks, stellar cartography) broken down into “blocks” of “knowledge” represented by “strings” – would the computer software actually be able to execute commands other than the 5 outputs available above? The simplifications of the world and the types of input-output available are too far removed from real-world abstractions and complexities to hold any weight.

I return to my Minecraft squirrel drama on the ledge. The squirrel program running inside Minecraft could be having a similar conversation to the one archived by SHRDLU :

Squirrel: I am sitting here.

Computer: You are indeed sitting here.

Squirrel: Should I move forward?

Computer: You should not. There is a vast ocean and you will drown.

Squirrel: Should I move left?

Computer: You should not. There is an ocean there too.

Squirrel: That sucks. Maybe I should move right?

Computer: Nope. Ocean all around, amigo.

Squirrel: Awww man. Shall I move backwards?

Computer: There is a block of earth there.

Squirrel: What about jumping? Can I jump onto the block of earth?

Computer: Alas, you can’t. There is a block of earth there too.

Squirrel: So… I should just sit here?

Computer: Sounds good to me.

The squirrel, like the SHRDLU program, takes “input” from the world (in this case, the computer is controlling what is in the world, but in the SHRDLU program, the world seems largely defined by the human-defined input.) The squirrel program is totally cool just sitting there, because it has gone through its programming and figured out that in order to stay alive (which squirrels in Minecraft apparently like to do) it should stay out of the water. The squirrel will never learn to dig through the earth or climb against the facade to get out. The program is quite content to execute its programming and chill.

So when I feel pangs of sadness that a squirrel is caught on the ledge, that is my human abstraction of what is going on. The squirrel program is actually quite happy where it is. But wouldn’t the squirrel also be quite happy to move around, too? When I’ve watched Minecraft mob patterns, I’ve noticed that almost all creatures feel an impulse to move around. If I unleash a pack of chickens into the wild, they’ll meander away eventually, often splitting off into different directions. Squirrels are similar, bounding away happily in the world. I have dug into the process of “artificial intelligence” in the mobs of Minecraft, I still feel the need to wonder – would the squirrel prefer to be moving, and does it consider that state ideal? I project the human emotion “happiness” onto the bounding squirrels and chickens of Minecraft – but could that be a fanciful description of something actually happening within the hardware.

While I know that aesthetically, I am sympathizing with the squirrels and chickens of Minecraft because they are kind of cute, I also have to wonder if from an artificial intelligence point of view, something deeper may be occurring under the surface. Of course, I can terminate the Minecraft program and walk away from the stranded squirrel completely. Brooks argues that “toys” offer too simplified a domain for serious study, and it is perhaps anachronistically futile to use an AI research paper from 1987 to contemplate upon Minecraft, a game released in 2009.

I am intrigued, reading Brooks, when he lists the engineering methodology behind building Creatures: “completely autonomous mobile agents that co-exist in the world with humans, and are seen by those humans as intelligent beings in their own right.” These artificial organisms would exhibit the following properties:

- Timeliness (as in reaction time)

- Robustness (minor changes in the properties of the world will not lead to a total collapse of the Creature’s activity or behaviour)

- Goals (the Creature should be able to maintain multiple goals, and, depending on the situation, prioritize one goal over another, as well as take advantage of fortuitous opportunities)

- Purpose (a Creature should do something in the world, should have some purpose in being)

In many ways, the Minecraft mobs satisfy these four requirements. The squirrel prioritizes staying alive over bounding about happily, the squirrel would jump up and try to flee if I hit it with my battleaxe, the squirrel reacts if I dig a path in the earth for it to escape the cliff and the squirrel has a purpose : it is a denizen of the forest, and makes the forest complete.

However, where Brooks and I may differ on interpretation of the concept of a Creature is in the words “co-exist in the world with humans” – players may enter the world of Minecraft, but are they really “in” the world of Minecraft? As pieces of software, does the squirrel program really “exist in the world” – is its physical existence as a tiny component of a hardrive a big detractor from its software, virtual manifestation?

The squirrel of Minecraft is an artefact running on the software foundations of a lot of artificial intelligence research. We can pause or “disable” the squirrel program, or the SHRDLU program, and when we re-engage the program it does not restart from scratch necessarily – depending on how Minecraft decides how mobs are loaded and respawned into chunks, that same squirrel may reappear, and reassess that it is still stuck between the ocean and a hard place. But is it really the same squirrel? Is it really manifesting a portion of intelligence? Would it prefer to be bouncing about happily rather than stuck on the ledge?

Or is this all besides the point – is the more interesting investigation with regards to how the player responds to the situation. So I ask you the question: if you found the squirrel stranded on the ledge, would you do anything about it? And why?

The post A Squirrel Is Stuck Between An Ocean And A Hard Place appeared first on &.

]]>The post BFC – BigFriedChicken’s Cook and Sort machine appeared first on &.

]]>BFC – BigFriedChicken’s Cook and Sort machine

How does the BFC Vanilla edition sort cooked chicken, feathers, and eggs into specific chests?

An industrial cooking and sorting machine. This device is the soul of the BFC and automates the process of collecting, cooking, sorting and finally storing cooked chicken, feathers, eggs and any anomalies (ie: dirt blocks, uncooked chicken, etc) into containers (chests).

To begin the process, the chicken brood is enclosed over hoppers (in our case, 3), these hoppers are placed so that they output towards the next hopper in line, with the final hopper output dropping down into a dispenser.

The dispenser will not shoot out eggs unless it is powered.

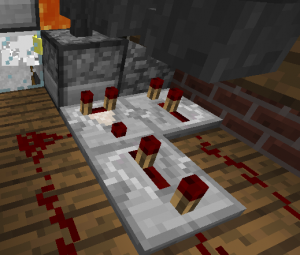

The mechanism that powers the dispenser is a circuit designed to launch eggs once they enter the dispenser through the hopper chain. The circuit uses a comparator in the “compare signal strength” mode in order to compare the state of the dispenser with the feedback signal to detect incoming eggs and to power the dispenser to fire them.

In “compare signal strength”, the comparator is off but

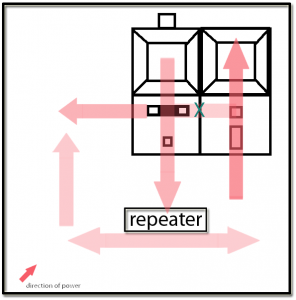

and so it is important that the comparator is properly configured so that its rear input faces the dispenser’s rear (figure 1).

Figure 2. The arrows show the circulation of power. The comparator will try and compare values on either side of it but cannot compare the repeater on the side because its power follows a linear tract. The X shows that the connection is not established and therefore ignored.

When there are objects in the dispenser, the comparator will compare that amount to its side inputs, these being red stone wire and a repeater. The comparator does not compare the signal to the repeater because the repeater’s output does not face the comparator (figure 2).

The comparator compares the value in the dispenser to the red stone circuit to its left. A repeater, its input towards the comparator, controls the rate at which the signal passes through the red stone circuit to ensure that the comparator’s signal does not instantaneously turn on the red stone wiring. This ensures that the comparator’s signal will be stronger than the red stone circuit.

Ex: if the dispenser has one egg, the comparator has a value of 1. It checks it’s side inputs and the red stone circuit will have a value of 0. 1 is bigger than 0, and therefore the Comparator turns on.

In the second example, I explain one of the reasons for using a repeater directly after the comparator. Although not necessary, the repeater ensures that the red stone does not instantaneously power on when the comparator does.

Ex 2: the dispenser has one egg, the comparator has a value of 1. It checks it’s side input and server lag or a malfunctions, and because the system does not have a repeater to delay the signal, its value also appear as 1. 1 is not greater than 1 and therefore, no power. Without power, the dispenser does not do anything.

When the comparator turn on, a signal passes through the repeater, which delays it by a fraction of a second, and circulates both left and right on the red stone circuitry. On the left, the signal powers the red stone adjacent to the comparator and powers the red stone to 1. As we have seen, when the comparator and the red stone next to it have the same value, the system turns off.

Simultaneously, the right side powers a repeater, that powers a block which in turn powers the dispenser which shoots out the object (egg). By shooting out the object, the dispenser value decreases and as a result the comparator turns off.

There is no danger of overflow of eggs into the dispenser because the hoppers only ever allow one item to transfer at a time. This ensure that this system constantly turns on and then off for each egg.

The dispenser shoots the eggs into an enclosure to produce chicks and from them, cooked chicken. The eggs are launched into an enclosed chamber over a hopper with a half slab, some hatch as chicks. The chicks are therefore elevated above the regular block level and only have a half slab area to circulate. Since chicks are only half a block high, they can move freely. A full block above the hopper, contains lava produced by a dispenser (figure 3). This dispenser is powered by toggling a button – while ON it produces the lava, and OFF it retracts the lava. Since a fully matured chicken is a block in size, once the chicks grow up, they surpass their half slab of livable circulation and the lava cooks them. In most cases the dropped item, cooked chicken and feathers, will fall through the half slab and into the hopper underneath it which is positioned with its output towards a chest. In some cases, the dropped item will burn.

A row of hoppers aligned with their outputs towards the next in line, lies beneath the chest (figure 4). The hopper pulls the items out of the chest and down the conveyer belt. The last hopper at the end of the belt has its output leading down into another hopper that leads down and into a chest. This chest, at the end of the line, will collect any surplus items that are not configured in the regular sorting system.

Figure 4. The conveyor belt hoppers each have their output leading towards the next hopper. This ensures that items move fluidly.

Figure 5. Conveyor belt hoppers, sorting hoppers, and chest. Note that the red torch is ON, at the bottom, to indicate that the hopper is locked and will not pass down items.

Beneath this conveyor belt of hoppers are three evenly spaced red stone sorting circuits designed to store specific items into their respective chests. The system works by taking advantage of a hoppers ability to lock when powered and to draw similar items within its inventory and use it to power red stone. In this way, when items travel through the conveyer belt, specific items (in our case feathers, chickens and eggs), will fall down into a lower hopper when they match (figure 5).

Hoppers work by shifting items in it towards its out put. In the assembly line, the items are pushed left, but, if there is a hopper underneath a hopper, items will fall down. When a hopper is empty, any items may travel through it, such is the case for the last chest on the conveyer belt. This chest collects any material our three configured hoppers will not collect. These configured hopper’s slots have been filled with 21 sticks and one chicken/feather/egg which is located in the first slot.

When a hopper’s slots are filled, it will try and collect additional material first through the first slot. For the sorting machine to function properly, one chicken (or desired item to be sorted) must be at the beginning of the slot line so that the hopper will constantly look for it. This hopper is specifically designed to allow only one item to travel through it (and into the next hopper below it which deposes it into a chest) at a time. This ensures that the sorting machine will never collect any sticks, but always the primary slot item.

Figure 6.

Just in case,

ex: 1 chicken, 6 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks (figure 6)

One chicken from the conveyer belt falls down into this hopper: 1 new chicken + old chicken = one chicken falls down into the lower hopper and into the chest before the hopper locks again (I will explain that process shortly). We still have 1 chicken, 6 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks and therefore the sorting machine will continue looking for chickens and not sticks.

Alright, so we now understand that the cooker function with a “compare signal strength” comparator coupled with repeaters to launch eggs into an enclosure that will hatch chicks that will cook when they mature into chickens. The cooked chicken then falls into a hopper located under the enclosure, into a chest, and then is sucked into the hopper conveyer belt which will then sort them into four categories: chicken, feathers, eggs and everything else. But how does the sorter work? Where does it obtain its power and ability to transfer only one item at a time down from the sorting hopper into the lower hopper and into the chest? Why don’t all the items in the sorting hopper (1 chicken, 6 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks) not fall down also? The answer, a comparator and repeater process again.

Figure 7. The comparator is on “Measure block state” mode. Out put towards the red stone wire. It is difficult to see, but sparks are coming out of the first block to show that it is powered. The second block of red stone wiring is not sparking.

Instead of using a “Compare signal strength” (CSS) comparator as we did with the cooking section of the BFC, the sorting area utilities a “measure block state”(MBS) comparator and its output facing two blocks of red stone wire (our circuit material). Unlike the CSS, the MBS “will treat certain blocks behind it as power sources and output a signal strength proportional to the block’s state.” This allows the user to control how many items fall into the lower hopper, and ensures that the sorting hopper does not empty itself out into the lower hopper. But how?

Alright, so the hopper is locked using a red stone torch set ON. The comparator has only enough power to power ONE of the red stone wires (figure 7). When one cooked chicken falls down into the sorting hopper, the additional power of one chicken will power the second red stone wire block, which will activate the repeater that will turn off the RED STONE TORCH long enough to allow one item to fall down into the unlocked hopper before locking again. The repeater ensures that only one item falls down at a time so that the sorting hopper does not empty itself out.

How does the comparator generate energy? Why does it only power one block when we have 1 chicken, 6 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks, 5 sticks, but two blocks when there are two chickens?

It is not readily obvious how this works, but a member of the Minecraft Wiki community shared this mathematical formula to explain how to calculate signal strength from any given item.

signal strength = truncate(1 + ((sum of all slots’ fullnesses) / number of slots in container) * 14)

1 + ((sum of all slots’ fullness)/number of slots in container) x 14 = amount of red stone blocks that will be powered.

To begin, we must calculate the amount of items in our hopper and divide each by their full amount. In our case, the items we are using all stack up to a maximum of 64.

1/64 + 6/64 + 5/64 + 5/64 + 5/64 = 22/64

22/64 = 0.34375

0.34375 divided by amount of slots in a hopper (5) = 0.06875

0.06875 x 14 = 0.9625

0.9625 + 1 = 1.9625

Truncate this number and we get 1

therefore, this formula powers 1 red stone block.

It is important that the non-truncated number is 1.9625 because with an additional chicken, the truncate is 2.

22/64 + 1/64 = 23/64

= 0.359375

= 0.071875

= 1.00625

= 2.0624

truncate 2

With the second block powered, the repeater turns off the torch long enough for one chicken to fall down into the chest and return the power to 1. The sorting machine absolutely needs two blocks powered for items to fall.

Why not use other items such as signs that stack up to 16?

Using signs or other items that stack up to 16 actually impede the machines functionality:

ex: 1/64 (our chicken) + 2/16 + 1/16 +1/16 + 1/16

1/64 + 5/16

0.015625 + 0.3125

= 0.328125

= 0.065625

= 0.91875

=1.91875

= Truncate = 1.

BUT, if you add an additional chicken:

2/64 + 0.3125

= 0.34375

=0.06875

=0.9625

= 1.9625

truncate = 1

Not enough power.

Therefore, using items that stake up to 16 will decrease the amount of cooked chicken gained as this system would need 3 or more chickens before having enough power to let one pass. The other system ensures that the user has the most cooked chicken gain.

Why not add more signs? Adding just one additional sign will power two blocks and thus render the sorting machine useless as everything would empty out of the hoppers (as the constant power will allow the repeater to keep turning off the red stone torch and letting more items down into the chest). Using this energy, the system is able to collect cooked chicken and other material and place it into specific chests.

Have fun with your BFC

http://minecraft.gamepedia.com/Redstone_Comparator

The post BFC – BigFriedChicken’s Cook and Sort machine appeared first on &.

]]>The post Building Online Community Despite The Gamers appeared first on &.

]]>This week, instead of a weeknote focused on #BigFriedChickenCompany and the work my comrades Marie Christine, Sean and Saeed have been contributing to, I’d like to devote some thought to a greater picture with regards to Minecraft.

Minecraft is somewhat singular. It’s a computer program which can be run individually by one person, or on a server as a space that can be shared by a myriad of different communities. “Minecraft the Phenomenon” is the runaway success of a lone 30 something high school drop-out programmer nicknamed Notch. The indie developer’s dream is to build another Minecraft – where the programming can be shoddy, the execution hit or miss, but the community rock solid. Multiplayer games are very fashionable lately, but whether one is part of the big bucks AAA industry or the indies starving in the garage community, everybody wants what Minecraft has: the sheer volume of people who love Minecraft, mod Minecraft, and build on Minecraft.

Microsoft this month put a price tag on the Minecraft Phenomenon – 2.5 billion dollars US.

Minecraft to join Microsoft http://t.co/ebAuoNC7mO pic.twitter.com/LePrYjCysC

— Microsoft (@Microsoft) September 15, 2014

This week, I’d hoped to write a little more on the communities of Minecraft I’ve experienced, but my attention was pulled away from this topic by the real world. I’ll be touching on my own experiences, but within a much larger context than my experiences either on the TAG minecraft server from last spring, or on the mLab server in which the #BigFriedChickenCompany is now being built anew.

A few weeks ago, I caught wind on twitter of a then-unconfirmed rumour that Mojang, the studio behind Minecraft, was being purchased by Microsoft. While the ideology behind the purchase did not really perturb me (“oh noes! my favourite billion-dollar indie videogame is going to become billion-dollar corporate sludge!”) I was intrigued to hear about what was going on with Minecraft’s renowned creator Notch.

The reaction on twitter against Notch was, at first, overwhelmingly negative while a certain core of gamers complained that Notch was “selling out.” Major news outlets even picked up on some of the negativity circulated by fans of the game. Notch wrote a blog post about his exit strategy – the blog post, written in the form of a letter to the Minecraft fans, reads like the writing of someone on the edge of burnout and emotional collapse. Notch writes that he doesn’t have the connection with the fans that he thought he did, he can no longer accept the mental and emotional strain of heading Minecraft (the program, the community and the phenomenon now indistinguishable) any longer.

The reason I’m focusing so much on Notch’s goodbye letter is because of the following paragraph:

I was at home with a bad cold a couple of weeks ago when the internet exploded with hate against me over some kind of EULA situation that I had nothing to do with. I was confused. I didn’t understand. I tweeted this in frustration. Later on, I watched the This is Phil Fish video on YouTube and started to realize I didn’t have the connection to my fans I thought I had. I’ve become a symbol. I don’t want to be a symbol, responsible for something huge that I don’t understand, that I don’t want to work on, that keeps coming back to me. I’m not an entrepreneur. I’m not a CEO. I’m a nerdy computer programmer who likes to have opinions on Twitter.

If you haven’t seen that Phil Fish documentary, please do. To talk about Phil Fish has nothing to do with Phil Fish but everything to do with fame, audience, the internet, and indie videogames.

It dawned on me then, that Notch leaving games is an event that cannot be unpacked without also addressing the extremely broken state of videogames (the programs, the community, the industry). The community, hobbled around an identity generated by corporations and viciously attacking those that don’t belong, is rabid. This concept of a removed, anonymous, money-throwing glob called “audience”, in the age of independent video game developers sharing on Twitter and the internet, is revealed to be a toxic place. Traditionally, the storyteller sitting around a campfire used the rhythms and whims of the audience to the story’s advantage. Where videogames are concerned, and game makers and story tellers are separated by a thin veneer of… something … the discontented audience glob continues to act like a pack of rabid dogs.

Of course, I’m talking about #GamerGate. (To bring you up to speed, I do believe the best article on the subject so far is this article on Cracked. Yes, the listicles of clickbait website.)

The sheer vitriol thrown at Anita Sarkeesian and Zoe Quinn in the past year by the amorphous glob known on Twitter as #GamerGate is terrifying. Offline and online, people are rallying together and asking themselves what on earth is going on. I’ve attended formal meetings at my university with fellow game makers, writers and researchers wondering what can be done to make video games a better place. Women especially are worried of having their real names on their projects. People are attacked online constantly, but there’s a concentration of inane, repetitive cruelty in the GamerGlob that’s making women question their decision to work in video games. Many have left in the past few months. Even Notch, a freshly-minted billionaire and infinitely more privileged than most targets of harassment and ire, writes that he afraid of losing his sanity over Minecraft and its relationship with the amorphous “audience” glob.

There is something wrong with the community that Microsoft just paid 2.5 billion dollars for. When I first began playing Minecraft for university, I was enchanted by the nature of the online community which was so different from my experiences playing Guild Wars and World of Warcraft. Six months later, the honeymoon’s over, I’ve seen the good, the worst and the ugly. I’ve seen communities built on Minecraft and wane on Minecraft, reflecting real world and in game rhythms. I’m still reflecting about what it means to build a community of modders and builders – as well as thoughtful gamers. That community cannot be built, on the TAG or mLab Minecraft servers or anywhere else, without a good hard look at the larger contexts in which these communal spaces exist.

Update

A really amazing game developer who on twitter goes by @mcclure111 astutely observes that this post outlines a problem but really doesn’t offer anything concrete as a solution.

I offer this post as a piece of the process of recognizing how deeply felt the warping of “audience” and “creator” is, how far removed videogames are from “story” and “storyteller” (was there ever a link at all?) and how poisoned the “gamer” identity is/always was. I am still reflecting on a solution. I hope you will too.

Further Reading

Carolyn Jong at TAG has compiled a very good list of resources here.

The post Building Online Community Despite The Gamers appeared first on &.

]]>The post Why #BigFriedChickenCompany appeared first on &.

]]>This past week, I spent a large amount of time in a car driving around the Atlantic provinces of Canada. Most of my time was spent either driving along the coast or through what was once farm country.

Much of my time during this road trip was spent reading, as I was unable to go online and play Minecraft. I alternated between reading Ian Bogost’s Alien Phenomenology and Anna Anthropy’s Rise of the Videogame Zinesters.

Click to view slideshow.During my time reading and thinking, I was wondering about this blog post and what exactly I would write. I had read Bogost’s chapter on Carpentry before and knew what to expect, it had been a while since I last read this particular piece. Refreshing my memory allowed me to rediscover Carpentry and contrast it not only with Anthropy’s work, but also with my own adventuring in the Maritimes.

When we spend all of our time reading and writing words – or plotting to do so – we miss opportunities to visit the great outdoors. (Bogost 90)

So much of my time in Minecraft is spent travelling long distances in search of loot and materials to build and build and build. Here in the real world, driving from Montréal to the coast of Nova Scotia is a round trip of about 2,480 km. Crossing that kind of distance on the mLab server is not trivial, but completely unlike the real world when factoring resources like time and energy.

I started to think about a talk I’d recently heard by games scholar Rilla Khaled on reflective design in videogames (talk slides here). Rilla’s emphasis on the way clarity and reflection is sacrificed in videogames for the sake of “immersion” can lead to players losing time that could be spent reflecting and thinking. While books as an art form have plenty of room for escapism, videogames is a genre dominated by the pursuit of “immersive play” at the detriment of reflection. By obfuscating the passage of time in games with this marketing concept called “immersion”, games become “time sinks” in which players lose grasp on the time spent on a game.

I love playing Minecraft, but I’m not sure the manner in which I play Minecraft prioritizes reflection. The more I thought of prioritizing “clarity over obfuscation”, the more I wondered “Why build a #BigFriedChickenCompany in Minecraft anyways?”

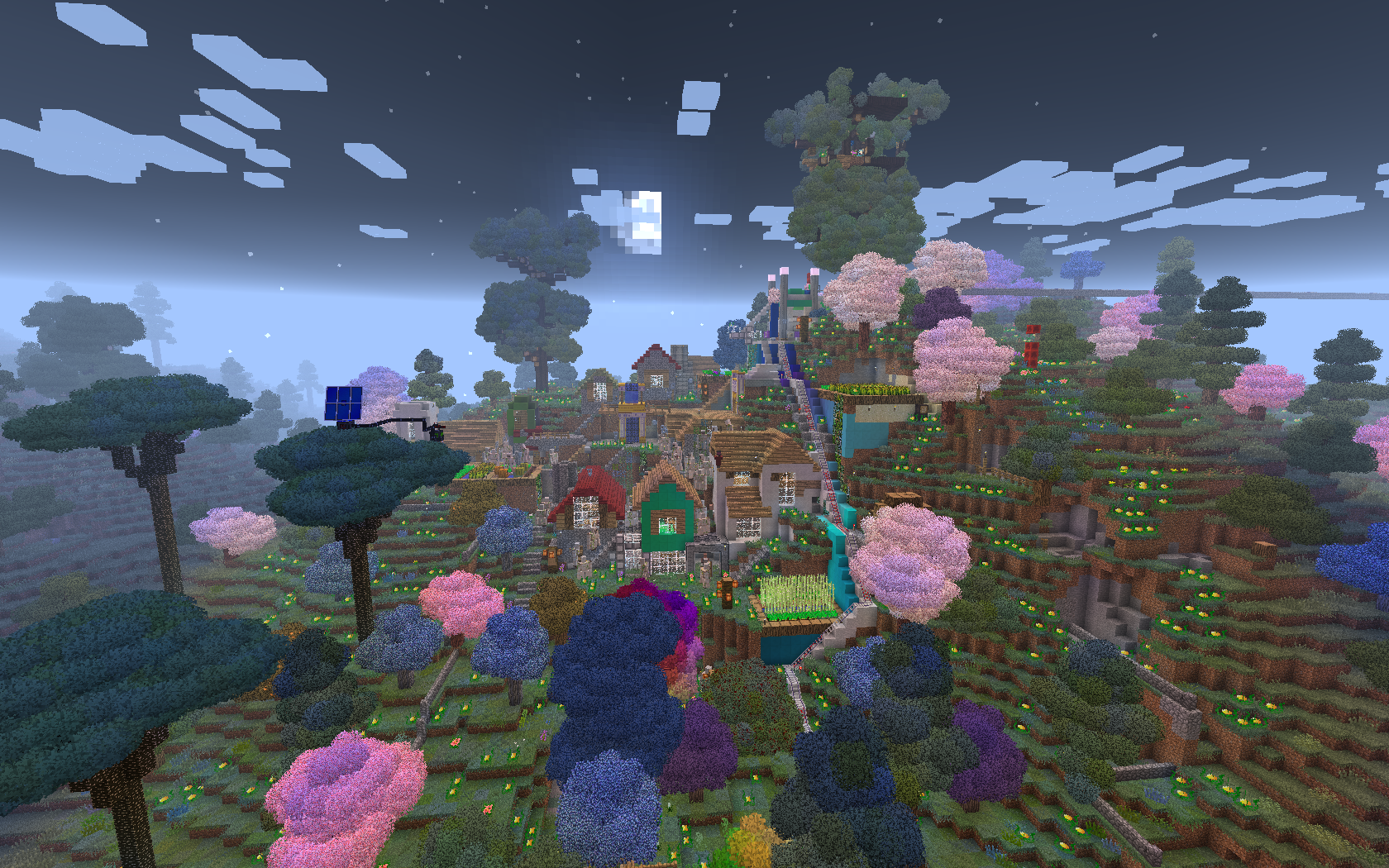

Currently, our server, named “mLab Prime”, has a small community developed around the spawn point called “N00b’s Landing”, a headquarters called “Flower Hill Head Quarters”, and an industrial factory/power plant type building on a beach called “Site Lambda”. Just down the beach from Site Lambda, following a path of redstone in the sand, a player will see the letters “BFC” floating against the tree line. BFC stands for Big Fried Chicken, and is the company I am helping put together on Minecraft with a handful of other players. Building a fast food franchise in a game like Minecraft is a thought-provoking next step for mLab Prime. Minecraft is a resource gathering game – on a server in which players share resources and have grouped close together, starting a fast food franchise is an odd intrusion of “real world” capitalism into the otherwise idyllic “mLab Prime”. Our community in Minecraft spends a lot of time creating resources that everybody can share – N00b’s landing, Flower Hill HQ and Site Lambda are quite heavily stocked with resources and a train system connecting various islands. A newcomer to the game saves thousands of hours that would otherwise be spent collecting materials and exploring the area by foot. Time and energy saved, obfuscating the dangers of Minecraft (exploding mobs, dying of starvation) and taking care of the first steps of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. A fast-food franchise, which could take care of the food needs of the entire community of mLab Prime, may feel like a capitalistic next step, but not completely alien to the already industrialized area in which we started building the #BFC construction site.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Building an industrial-level chicken roasting complex in Minecraft is not trivial, but it is also completely unlike building one in real life. While we will have to worry about energy resources, hoarding chickens, and dealing with maintaining a steady input and output of chickens, the costs in terms of time and energy is quite different.

On my way back to Montréal from the Maritimes, I was reminded of this quite vividly. Around two in the morning just north of Victoriaville, Québec, we had to stop for gas. As we pulled into the parking lot, I heard a strange noise. It was coming from a huge truck parked a few metres from us.

Click to view slideshow.The strange sound was the screaming of pigs crammed into a truck. The reality of industrial-level agriculture and farming crashed down on my bleary sleep-deprived mind. I approached the side of the truck carefully, not wanting to excite the caged animals even more than they already were. The pigs were covered in lines of paint (probably some sort of branding) and many were attacking each other. Quite a few were lying on the floor, limp, as other frightened pigs trampled on top of them.

The moment outside of a gas station in rural Québec was a pretty stark reminder why the economic principles that hold up the fast food industry in North America are vile. I was glimpsing a tiny part of it. I felt disgust well up in my chest when I got back into the car and saw my notes on #BigFriedChickenCompany. I flipped through Anna Anthropy’s book, looking for something she has said on videogames that has stuck with me for a long while now:

What are videogames about? Mostly, videogames are about men shooting men in the face. Sometimes they are about women shooting men in the face. Sometimes the men who are shot in the face are orcs, zombies, or monsters. […] if one looked solely at videogames, one would think the whole of human experience is shooting men and taking their dinner orders. Surely an artistic form that has as much weight in popular culture as the videogame does now has more to offer than such a narrow view of what it is to be human. (Anthropy 3)

In building #BigFriedChickenCompany, ignoring the ethical repercussions of real-world factory farming is not unlike building a videogame in which the only mechanic that matters is shooting moving targets. We cannot blindly create industrial structures and ignore the way in which we treat even pixelated creatures, because that further obfuscates our own real-world relationship with our food.

Click to view slideshow.Fast food franchises muddy the relationship between demand and supply. Acquiring large amounts of fried chicken in ever greater amounts is consumerist, and the ease in which #BFC plans to feed the entire server risks sacrificing reflection on what we eat.

Once the first #BFC building is complete, I will be looking into building humane, and likely time-intensive farming and restaurant Minecraft franchises.

Follow #BigFriedChicken on tumblr.

Tweet Your Love for #BigFriedChicken!

Works Cited

Bogost, Ian. Alien Phenomenology Or What It’s Like To Be A Thing. 2012.

Anthropy, Anna. Rise of the Videogame Zinesters. 2012

The post Why #BigFriedChickenCompany appeared first on &.

]]>The post 2013-06-12 The Newbies Are Coming appeared first on &.

]]>I have just moved into the M Lab, I think I was the first one, but now I see Dr. Consalvo’s computer sitting comfortably in the corner. I am surrounded by thousands of dollars in PC video gaming equipment and feeling jealous of the Critical Hit Incubator’s resources. Having just returned from the Japan Game Studies Conference and the Canadian Game Studies Conference, I have been sizing up my duties as a PhD student. As it stands, I have come to terms with the fact that I need to represent myself better (detailed and frequent), which is why I have assented to this intriguing weeknote format. Hopefully I will be able to structure a coherent self over the next 208 weeks of my doctorate with these blog entries aiding my identity formation. That said, I want to talk about all the amazing people I have been hanging out with who are about to be heavily involved with video game research at Concordia.

Yesterday, I bumped into an old friend and long time board gaming partner Rainforest Scully Baker, who tells me he has won an undergraduate research assistantship and is working with Mia on speed running culture all summer. I sat and watched him play Sonic Adventure 2 on the Dreamcast for an hour as he repeatedly failed to beat his previous best times. Hopefully he will come do a game studies M.A. in Fall 2014.

Speaking of game studies M.A.s, two days ago I met up with Pierson Browne, who is coming to do his M.A. in the Fall. We both audited Pippin Barr’s course on game design, where Pippin told us about his attempts to publish a new iPhone game which subverts control schemes to make people look ridiculous while playing on metro. Pierson is going to be working on representations of nuclear arms in games with Mia.

Six days ago, I hung out with Skot Deeming in Victoria. He presented after me on his curatorial practice in Toronto. We talked about Queer Arcade and getting my work “Get’s It Better: Poor, Ugly, Gay, Stupid, Sick” through the challenges of being a board game in a museum space (possibly the worst way to exhibit board games to be honest). He’s coming to do his Doctorate in game studies in the Fall.

So yeah, needless to say, I am extremely hyped for whats to come with all the awesome people getting involved in games at Concordia.

The post 2013-06-12 The Newbies Are Coming appeared first on &.

]]>